‘Don’t let what you can’t do interfere with what you can do.’

John Wooden (1910-2010), NCAA basketball coach

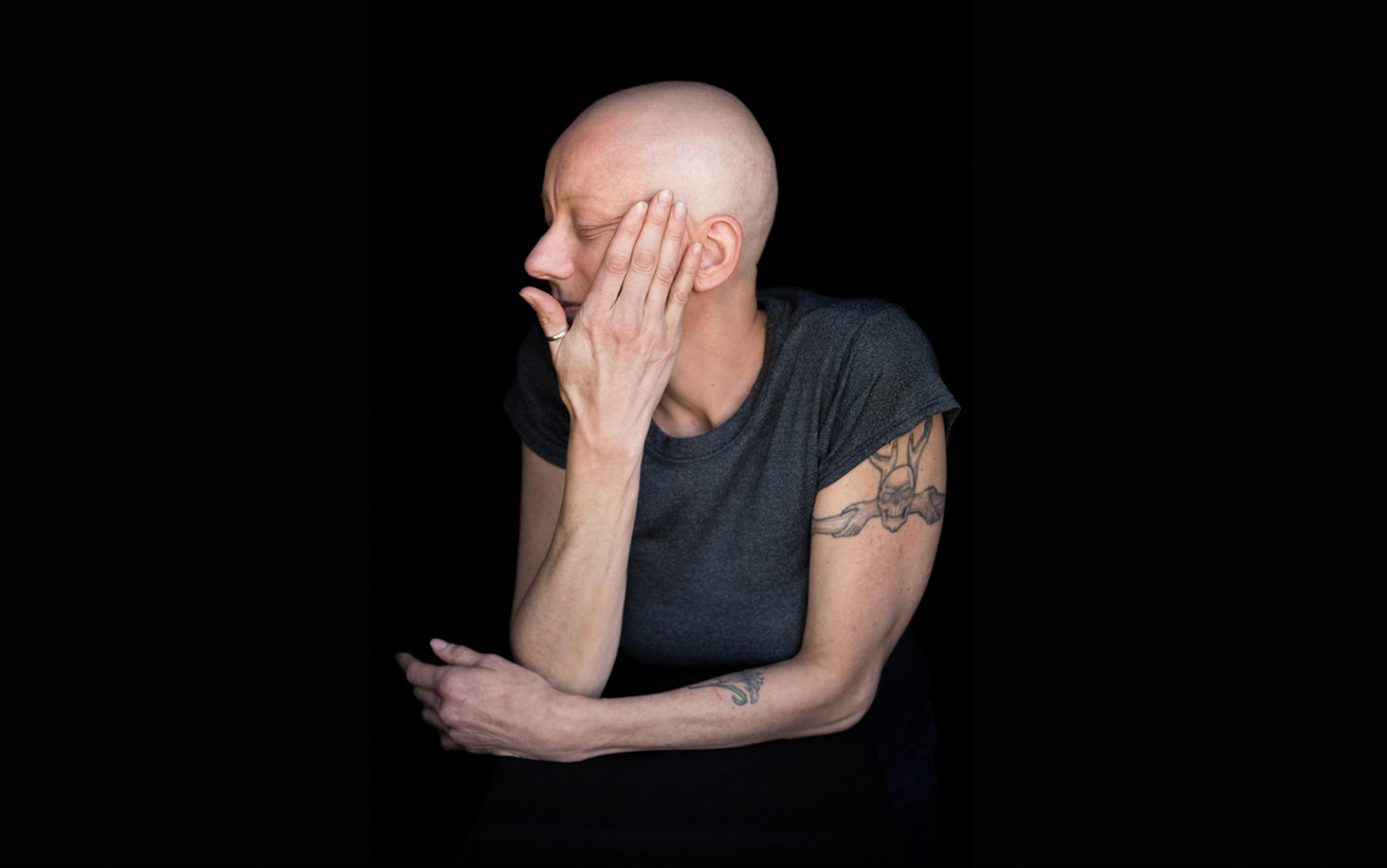

Before Donna got her diagnosis, she thought of herself as a musician, a busy professional, a volunteer, a mother, a grandmother. After she got her diagnosis – Parkinson’s disease, at age 58 – she thought of herself as a patient. The time she used to spend engaging in the things that gave her life meaning was eaten up by doctor’s appointments, diagnostic tests and constant monitoring of her symptoms, her energy, her reactions to medication. Her sense of loss was profound and undeniable.

Unfortunately, Donna’s experience is all too common. Heart disease, arthritis, multiple sclerosis, diabetes, depression, cancer, asthma, Crohn’s disease, cystic fibrosis, autoimmune disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, Lyme disease: the list goes on. I would guess that most people know someone close to them who is suffering from one of these debilitating chronic conditions, if not struggling with a diagnosis themselves. Globally, three in five deaths are attributed to one of four major diseases – cardiovascular disease, chronic lung conditions, cancer or diabetes. Moreover, approximately a third of adults suffer from multiple chronic conditions, wreaking untold havoc on healthcare systems and economies across the globe. In developed countries, it might be closer to three in four older adults who suffer from multiple conditions. The proportion of patients with four or more diseases is expected to almost double between 2015 and 2035 in the UK alone. Frighteningly, these statistics don’t even account for chronic illnesses in children, which are on the rise. In sum, this means that billions of people are, at best, not functioning at their highest level and, at worst, are severely debilitated, living limited lives, and requiring chronic medical care.

The bigger questions of how to prevent these illnesses or resolve this global health crisis are beyond me. I am not an epidemiologist, public health expert, economist or even a physician. However, as a clinical psychologist, I see many people trying to navigate the daily vagaries of chronic afflictions. I’ve worked with people who have been diagnosed with various forms of cancer, Parkinson’s, cystic fibrosis, Lyme disease, obesity, all manner of cardiovascular diseases, multiple sclerosis, brain injuries, paralysis and many other illnesses. Naturally, I also see people on a regular basis who are dealing with chronic mental health issues, such as depression, anxiety, trauma, bipolar disorder and so forth. The causes of these conditions are varied and multifaceted. The underlying factor for all of them, however, is that, in the absence of a cure, people want to live the best life they possibly can, regardless of their affliction or disability. While each person and each condition presents its own set of challenges, there are some unifying principles in helping people who are suffering from chronic illnesses to live better, more meaningful lives. In my practice, I approach these issues from a therapeutic perspective known as acceptance and commitment therapy, or ACT (said as the word, not the acronym). I encourage anyone dealing with similar issues to learn about this approach, as it has been helpful to my clients and countless others.

Generally, living as rich and meaningful a life as possible when you are struggling with a chronic illness requires a great deal of psychological flexibility. With chronic illness, rigidity in your thinking and behaviour is the greatest barrier to living well with your illness. The only thing you can count on is the fact that you never really know what your day is going to look like, and that things are always changing. How are you going to feel today? This morning? Later this afternoon? What will you be able to do? How much rest will you need? How clear will your head be? How much pain will you have at any given moment today? How bad will the medication side-effects be? Planning – for anything – can be an excruciatingly difficult task and, since we are typically creatures of routine, we hang on to those routines as much as we can. This is generally a good thing – we like structure and predictability, but chronic illnesses can make this quite challenging, and sometimes impossible.

Psychological flexibility is the idea that we need to be present with what is happening right now, free of judgment, and to respond in a way that moves us forward rather than getting stuck in the emotions or feelings of the moment – anger, frustration, sadness, pain and so forth. While becoming more psychologically flexible might seem like a daunting, if not impossible task, it is not a talent available only to a select few. Rather, it is a skill, and any skill can be learned by just about anyone with enough practice. Below are some approaches that you can use to help you increase your psychological flexibility and, I hope, help you live a more meaningful life, even if you have a chronic illness. These are the same things I try to help clients such as Donna do in our work together, and I like to think they’ve found them useful in navigating through the darkness of chronic illness. If they resonate with you at all, I recommend doing some further reading on ACT and maybe working with a professional ACT therapist to help you live the best life you possibly can.

Be the thinker, not the thought: this phrase refers to how we handle our internal voice, the constantly running commentary that we experience all day, every day, and can never seem to silence. For whatever reason, that inner voice can be very critical, judgmental or even downright cruel. We also tend to listen to it way too much. Since human beings are rather egocentric, if our mind is telling us something, we tend to automatically believe it to be true. This contributes greatly to our perception of reality, and drives our emotional reactions and behaviours, but often in unhelpful directions. For example, if you’re dealing with a chronic illness, you might be plagued by thoughts of being burdensome to your family or loved ones. In Donna’s case, she was troubled by her limited capacity to do the things she used to enjoy, the things that gave her life meaning. Be the thinker, not the thought simply means increasing your awareness of the thoughts you are having, being more observant of your own thought processes, putting some distance between the thought and reality, and then making some better decisions about whether or not to engage with them.

But how does one do this?

I am not suggesting that you try to eliminate or control any of your thoughts; this would be a futile endeavour. Thoughts will arise in your mind, and there they are – trying not to think something actually requires you to think it, so it is simply not possible to do. Instead, you should notice the thought, then try to react in a better way so that you can separate yourself from it. It’s one thing to think ‘I am a burden’ but an entirely different thing to notice yourself having the thought that you are a burden.

This difference might seem like semantics, but it’s not. If you notice, then you can decide how to respond. If the thought is helpful to you at the time, then run with it. For example, if you think that it is time for your medication or that your family loves you and takes good care of you, then of course engage with those thoughts. If, however, you’re having thoughts about being a burden, and notice that and decide it isn’t particularly helpful, then you can figure out how much attention and energy you want to give this thought. Maybe simply noticing it and shifting your focus to something more productive would be the best course.

It’s important to note that I’m not encouraging you to argue with a thought, or convince yourself of its truth or otherwise, or in any way try to alter it. In this context, truth matters much less than function, so if the thought is of little use in moving you forward, no matter how true or false, it is probably best to shift your focus away. Donna’s recurrent thought – Everything I loved to do has been taken from me – was of no functional use. Similarly, it’s hard to come up with a good use for the thought that you’re a burden. So, notice the thought, decide it’s not useful, let it go, and move forward.

Allow yourself to feel what you’re feeling, move through it, and turn your attention to more meaningful pursuits

Be open to acceptance: this is perhaps the most difficult and misunderstood concept of ACT. For many, especially those dealing with a chronic illness, when they hear the term ‘acceptance’, they get upset. They liken it to being told to suck it up, to just deal with it or to stop complaining. In many contexts, this might indeed be the message that’s being sent with this word, but this is not the case from the ACT perspective. In fact, sucking it up and not complaining is often the opposite of acceptance. If you’re doing those things at the request of ‘well-wishers’, you’re probably denying your experience, stifling your natural reactions and avoiding reality.

The nature of chronic illness is that it is ongoing, and in many cases degenerative or permanent. Recognising when you have little to no control over something can help you to stop struggling against it. Validating – not minimising or negating – your experience can help you to honestly assess your condition, your options and your choices.

Allowing yourself to feel what you’re feeling can help you to move through it, and turn your actions and attention to more meaningful pursuits. For example, research on individuals with spinal cord injury in Canada suggests that those who reach a state of acceptance about their condition end up adapting better, being higher functioning and feeling more positive about their lives. This is not to say that, if someone with such an injury had an opportunity to be able to walk again, they shouldn’t pursue it. It is to say that spending all of one’s time and energy trying not to feel a certain way, or trying to change a currently unchangeable situation, is a fantastically inefficient and ineffective way to move through life. There is a time and place to fight your illness, but it is not 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Dropping the moment-to-moment struggle, and accepting where you are and what you can do in this moment can be powerfully transformative. It frees up energy and time to engage with family, friends, hobbies, leisure activities, rest and so forth.

Donna is a musician and had been a gifted guitar player. However, her Parkinson’s made it so she was no longer able to play with the same level of skill. At times, she could hardly play at all. As you can imagine, this was devastating to her. For a period of time, playing guitar was fraught with distress, anger, anxiety and frustration. Ultimately, her choice was to avoid those difficult feelings by never playing again, or to accept her current limitations and engage in an activity she loved to the best of her current ability. She had to lean into the pain of losing some of her skills in order to experience the joy of playing at all. Once she let go of her expectations, stopped avoiding and trying to control difficult emotions by accepting where she was, she found the joy in playing again. She was even able to grow differently as a musician because the illness forced her to think about playing things in new ways. This doesn’t mean it wasn’t sometimes painful for her to remember what she used to be able to do, but not letting that pain dictate her decisions is what ACT means by acceptance. This is critical to psychological flexibility and leading a meaningful life.

Stay present: you probably hear a lot about being mindful, meditating, staying focused on the now, not getting stuck in the past or caught up in the future. This is all good and wise, but what does it actually mean? What if your present is painful and difficult, why would you want to stay there? Staying present is another tricky concept.

From an ACT perspective, it means paying close attention only to what’s happening in this very moment, in your body, in your mind and all around you. This is a hard thing to do: it does not come naturally because our minds don’t easily allow it. We’re always looking for the next thing that might hurt us, regretting or reliving the past, worrying about the future.

The problem is that, when you are not present, it compromises your ability to move through your current situation. A big part of noticing your thoughts, for example, is being present with the moment. Regrets about the past and worries about the future do nothing for your current situation. You need to deal with what’s right in front of you, be it pain, anger, resentment, guilt, joy, fear or love. Whatever it is, it is with you right here, right now. Your job is to try to be present with it, even dig into it, because when it comes to emotions and physical sensations, there is no way over, no way under, and no way around – there is only through. And you cannot move through something if you are not present to it. Not being present is often a form of avoidance, which tends to get us into more trouble than if we just allowed ourselves to feel what we’re feeling in the first place.

Take Donna as an example. When she’s having difficulty functioning, she might spin into worry about what she can’t do, what she’s missing out on, and what a bad day means for her future. On days like this, she might get caught up in the past or the future, but she has symptoms that are bothering her right now, in the present. Once she’s identified them, named them and looked at them without judgment, she can try to turn her attention to other things that are present too. The birds are chirping. She takes a deep breath. The breeze feels good on her skin. She puts on a record and enjoys the music. In fact, she hears something in it that she probably wouldn’t have noticed when she was in high gear. This is a better way to spend a ‘bad’ day than ruminating, regretting and worrying. In fact, there can be a lot of joy and pleasure in the present moment even on the worst days.

Being here now, not there then, is like being present with your current self versus your past or future self

Be here now, not there then: no one wants to be sick but, when we are, we tend to think of what we were like when we were well, or how we hope to be at some point in the future. There’s nothing wrong with remembering or hoping, but when you allow past or future versions of yourself to skew your perception of your present – when you make decisions based on how you felt then versus how you feel now – it can lead to bad outcomes.

Perhaps you were an energetic, productive person before you became ill, but now you have a fraction of the energy you did then. If you make decisions about what you can do based on your former energy levels, you’ll set yourself up for major problems. You might be exhausted for the next four days or you might hurt yourself, rendering you completely unavailable for any other activity or for your family. Being here now, not there then, is like being present with your current self versus your past or future self. It doesn’t mean you’ll be this way forever, it just means this is where you are right now, so make decisions about your life based on that, not where you were or where you wish to be. Ultimately, this will allow for better decision making and increased functionality.

In Donna’s case, if she views her guitar-playing based only on what she used to be able to do or what she fears about how she will play in the future, this would increase the likelihood of frustration, harsh self-judgment and maybe lead to her not playing at all. However, if she stays present with her current self, she is more likely to stay engaged with this meaningful activity, enriching her day-to-day life.

Know what matters: there are few things that will clarify your priorities and values like a chronic illness. It turns your life upside down. The things you thought mattered – such as meeting work deadlines, getting promoted, making a good impression at the neighbourhood party – all of a sudden matter a whole lot less. Use this clarity to guide your decisions and your behaviour. If your illness has shown you that your family matters most, then every new decision should be geared towards moving you in the direction of that value. In Donna’s case, she rediscovered her love of music for itself, and saw how her mastery of an instrument was only one way to engage with something she valued deeply.

Earlier I spoke of letting go of thoughts that don’t matter or aren’t useful; knowing what matters is how you decide what’s useful to you. The good news is that, while you might have little control over what you think or how you feel, you have 100 per cent control over what matters to you. Is it your health? Stay fully engaged in your treatment. Go to your medical appointments. Get the sleep and rest you need. Say no to things that you know will be too much. Say yes to things that you can manage and that matter. Take an inventory of the major areas of your life – family, health, friends, leisure, spirituality, vocation – and decide what matters to you, and move towards it.

It’s important not to confuse values with goals. Goals are achievable and have an end point, whereas values are consistent guideposts in your decision-making process that are never truly attainable. It might be a goal for you to be able to attend an important family event, but being engaged with your family is the value behind the goal. Once you attend the event, it’s over, but you never stop caring about your family. Goals tend to be aligned with your values, but they are not the same thing. When you determine your values, this is where you want to pour your energy. Then you can use this information to guide all your decisions. Does the thought of being a burden help move you closer to what’s important and meaningful? No? Then let it go and move on. When it comes back, just notice it and let it go again. When you have a thought that is consistent with your values, then run with it.

Pain in the pursuit of valued actions is purposeful. Pain without purpose is suffering

Donna loved playing the guitar, but what she really loved was music. When she couldn’t play guitar as well as she liked, she found other ways to engage with music. It is critical to find the underlying value of any activity you love so, if that activity becomes too difficult for you, you can find other activities that keep you engaged in the value. If you love art, then make art. If you can’t make art, then look at art. Visit it, learn about it, engage with it in whatever way you can. Always evaluate your thinking in terms of how useful it is in moving towards your values. Fully engage and immerse yourself in it.

I should clarify what exactly I mean by engagement because you might misinterpret this as always feeling like you need to be doing something. You don’t. You can (and probably should) engage in rest. Take a nap. Say no to things. Stop doing things if it gets to be too much. Give yourself permission to pursue your value of tending to your health and wellbeing. Good self-care is the foundation for everything else you do – nothing else happens if you don’t take care of you, so resting and taking time off is not only okay, it’s necessary. It doesn’t make you lazy, it doesn’t make you useless, it doesn’t make you a burden. It makes you a whole thinking and feeling person who is doing what you need to do to take care of yourself. Embrace it. If your value is rest, then rest. If your values are more ‘action’ oriented, then do so in whatever way you can and that makes sense for you.

Recognise, however, that your values will likely go hand in hand with your pain. Often, when pursuing values, we need to accept that pain will come with it. Donna experienced this with her guitar-playing. She knew that pursuing her value of playing music would come with pain and difficulty because it reminded her of what she could no longer do. She fully recognised this, but she also knew that, while it might be hard, it also mattered, which can make the pain and difficulty just a little bit easier to carry. This is the difference between pain and suffering. Pain in the pursuit of valued actions is purposeful. Pain without purpose is suffering. While there is certainly purposeless suffering in the world, and those with chronic illness know this better than most, not all pain has to be suffering. Connecting your pain to a value is critical in helping you lead a richer, more vital, more meaningful life.

Above all, ACT is an action-oriented approach, designed to increase your psychological flexibility to help you behave in ways that will improve the meaning and quality of your life. The acronym is no accident. The doing, whatever you decide that might be, is of paramount importance.

Chronic illness might have robbed you of much of your abilities. You might feel like a shell of your former self. You might not be able to walk around the block anymore, or even to walk at all. Some days, maybe you can’t even get out of bed. Maybe you’ll never get out of bed again. Your stamina might be gone. You might become incredibly fatigued by the simplest of tasks. Maybe you can’t think clearly, or you can’t be in a room with the lights on. Eating might be a challenge; enjoying food might be a thing of the past. You might be in pain – all the time.

With chronic illness, you can easily spend all day cataloguing what you can no longer do, but to what end? Does this move you towards your values? Maybe you can’t engage with your friends and family exactly the way you like; but if you can engage with them somehow, no matter how small, that is meaningful. Our lives are ultimately determined by our behaviours – by what we do – and any action, no matter how small it might be, that moves you towards your values is better than doing nothing or shutting yourself down because it’s no longer the way it was or how you ideally want it to be. Maybe you can’t read to your grandchildren anymore. Can they read to you? In what way can you engage with them that’s consistent with your values? While it might not be the ideal way, it is a way, and anything that moves you in that direction, no matter how seemingly small, is going to be better for you and those who love you. When we are actively engaged in value-driven behaviours, life is more meaningful, even if it is different than it was before.

You might not have a choice about your illness, but you do have choices about how to live with it

Eventually, Donna’s disease progressed to the point where she was no longer able to hold a guitar well enough to play it. Her illness took this away from her, but she realised that, while she loved playing guitar, her real love was the music. So she wrote. She listened. She fiddled with a keyboard because she found this easier to play. She went to concerts and continued to share her love for music with her friends and her family; she taught others the joy she found in it. She stayed engaged in whatever way she could, even though her ability to speak with her chosen musical voice was no longer present. What was her alternative path? A life with no music? She could have stopped playing the moment she felt compromised by her disease. She could have engaged with the anger, the anxiety, the frustration, the pain of losing her ability to play at a high level, but to what end? Would her life have been better?

Through her ability to be the thinker not the thought, to accept what she could not control and lean into difficult feelings, to be present in the moment and with her current version of self, to identify her values and move towards them, Donna ended up continuing and growing her love for music in a way that would not have been possible if she turned away due to the pain of it all. She made the seemingly unworkable work. Was it exactly how she would have liked it to be? No, but I think we can agree that the alternative was a darker path, leading to a bleaker life than necessary.

The statistics I cited at the beginning of this piece are staggering and terrifying. On that scale, it is easy to feel powerless against the wave of disease and illness seemingly sweeping humankind. But every global health problem has an individual circumstance, and this is where we reside and where we do the work we can do. Chronic illnesses are insidious. They can take over your life and the lives of everyone around you. They are seductive, trapping us in a vision of what we don’t have and what we don’t want.

You have every right to be angry, frustrated and resentful. No one should tell you otherwise. You feel how you feel, but you don’t have to let those feelings – or your attempts to control them – dictate how you live. If you can become more psychologically flexible, if you can break free of the rigid emotional confines of chronic illness, you can fashion a better and more meaningful life for yourself and your loved ones. You might not have a choice about your illness, but you do have choices about how to live with it. At any given moment, those choices are either moving you towards your values – the things that matter – or they are not. Choose the former – it will lead to a more meaningful life.