In the Khyber valley of Northern Pakistan, three large boulders sit atop a hill commanding a beautiful prospect of the city of Mansehra. A low brick wall surrounds these boulders; a simple roof, mounted on four brick pillars, protects the rock faces from wind and rain. This structure preserves for posterity the words inscribed there: ‘Doing good is hard – Even beginning to do good is hard.’

The words are those of Ashoka Maurya, an Indian emperor who, from 268 to 234 BCE, ruled one of the largest and most cosmopolitan empires in South Asia. These words come from the opening lines of the fifth of 14 of Ashoka’s so-called ‘major rock edicts’, a remarkable anthology of texts, circa 257 BCE, in which Ashoka announced a visionary ethical project. Though the rock faces have eroded in Mansehra and the inscriptions there are now almost illegible, Ashoka’s message can be found on rock across the Indian subcontinent – all along the frontiers of his empire, from Pakistan to South India.

The message was no more restricted to a particular language than it was to a single place. Anthologised and inscribed across his vast empire onto freestanding boulders, dressed stone slabs and, beginning in 243 BCE, on monumental stone pillars, Ashoka’s ethical message was refined and rendered in a number of Indian vernaculars, as well as Greek and Aramaic. It was a vision intended to inspire people of different religions, from different regions, and across generations.

‘This Inscription on Ethics has been written in stone so that it might endure long and that my descendants might act in conformity with it,’ Ashoka says at the end of the fifth edict. In the fourth, he speaks of his ethical project progressing ‘until the end of the world’, though one year later in the next edict he offers a sobering qualification; the project can succeed only as long as it is taken up and continued – ‘if my sons, grandsons and, after those, my posterity follow my example until the end of the world’.

As it turns out, Ashoka’s influence did outlast the shortlived Mauryan empire. Along with Siddhattha Gotama, the Buddha, whose religion Ashoka did much to establish as a global phenomenon, Ashoka was one of the first pan-Asian influences. King Devanampiya Tissa of Sri Lanka (c247-207 BCE) wanted to emulate him, as did Emperor Wu of China (502-549 CE); Empress Wu Zetian (623/625-705 CE) even wanted to outdo him. And on 22 July 1947, days before India achieved formal independence from Great Britain, Jawaharlal Nehru, soon to be the country’s first prime minister, proposed to the Constituent Assembly of India that the independent nation adopt an Ashokan emblem – the wheel of a chariot – for its new flag.

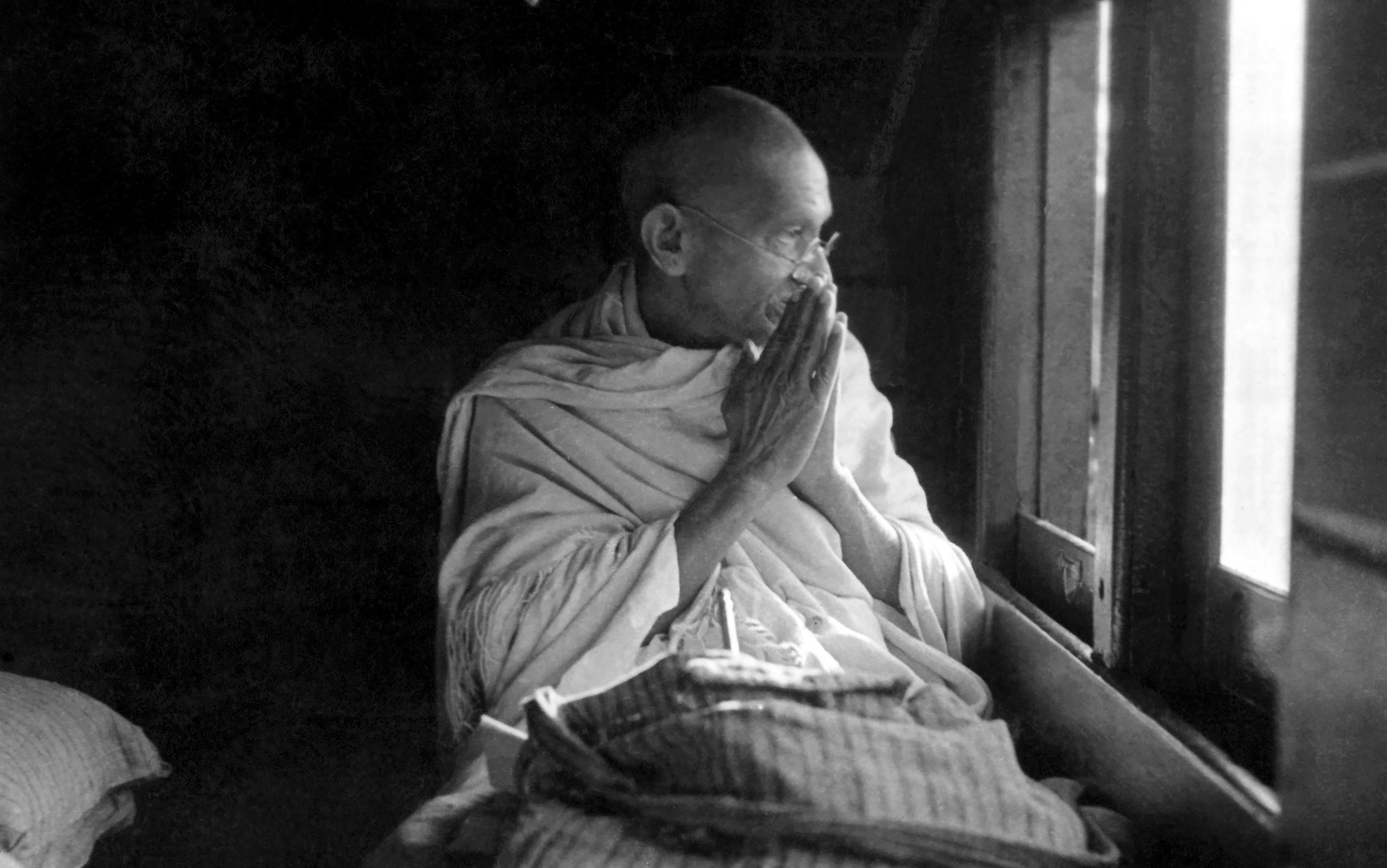

In doing so, Nehru proposed to replace the iconic cotton-spinning wheel associated with Mahatma Gandhi. The spinning wheel had graced the flag under which the Indian National Congress fought for freedom. And as it rolled through Indian history, the wheel had picked up many symbolic meanings. Gandhi’s spinning wheel, for example, could be read as a symbol of self-reliance, economic self-sufficiency, truth and self-assertion freed from violence. It was also a symbol of solidarity with the common man, as the farmers’ leader Panjabrao Deshmukh reminded the Constituent Assembly. Designed as the crowning ornament for a pillar rising anywhere between 40 to 50 feet above the ground, Ashoka’s wheel, no less symbolic of truth, was nevertheless a symbol conceived on a grander scale.

At issue in Nehru’s choice of a symbolic alignment of modern India with the trappings of Ashoka’s empire was the identity and the purpose of the state. The wheel of a chariot might stand for the concept of political power as dominion or for the power and influence of truth, as invoked in Buddhist symbolism of the Buddha’s first sermon which set into motion the metaphorical wheel of true doctrine. The Buddha renounced political power as inconsistent with the virtues he sought. Ashoka, as Nehru saw, did not. Ashoka’s wheel stood for an empire dedicated to peace.

Nehru urged the members of the Constituent Assembly to remember Ashoka’s empire as India’s ‘international period’: a time when the country took on a cosmopolitan role on the world stage, influencing her neighbours through culture and not war. Ashoka puts it memorably when he says, in the fourth edict, that with his reign ‘the sound of the drums of war has been replaced by the sound of Ethics’. This, along with the following from the 13th edict, captures the tenor of Ashoka’s ethical experiments best: ‘Victory through Morality is the best Victory.’ The conquest that mattered to Ashoka is self-conquest; power, expressed as control over one’s self-regarding attitudes and emotions, is now to be channelled into moral concern for others.

The experiment Ashoka’s Inscriptions on Ethics announce in the major rock edicts involves prying apart culture and violence on a scale scarcely to be believed. In South Asia, as elsewhere in the ancient world, the sacrificial offering of flesh from animals in fire was a paradigmatic religious act; hunting game, meanwhile, was a longstanding royal institution. Some ancient rulers, for example, built vast environmental preserves for royal households and their guests to engage in killing for sport. Ashoka inaugurated his ethical venture by announcing an end to such practices. ‘Here,’ said Ashoka, defining his domain, ‘no living being is to be sacrificed or harmed.’

Ashoka appears to have believed that change, however largescale, must begin at home. In his very first edict he shows us how to pay attention to the moral costs of one’s way of life. Styling himself as ‘The Beloved of the Gods’, Ashoka speaks of the way in which the royal household contributes to harm:

Formerly, in the kitchen of Beloved-of-the-Gods … hundreds of thousands of animals were killed every day to make curry. But now with the writing of the Inscriptions on Ethics only three creatures, two peacocks and a deer are killed – and the deer not always.

Ashoka’s edict was composed in 257 BCE. In 331 BCE, or 74 years earlier, Alexander of Macedon was reportedly stunned to encounter a pillar in the palace of Darius in Babylon. It listed that 100 geese or goslings were part of the daily menu. Ashoka’s ‘hundreds of thousands’ is even harder to credit. Yet it is likely intended to be suggestive and not documentary in spirit. Ashoka used the same number in his 13th rock edict to describe the number of people killed in the conquest of Kalinga in 261 BCE. There, Ashoka had been victorious – the architect of a conquest so complete and devastating that it cured him of imperial ambition altogether. To hear Ashoka tell it, what shook him was not the extent of devastation alone – ‘the killing, dying and deportation that take place when an unconquered country is conquered’ – but also the way in which the misfortunes of war are distributed. It appeared to Ashoka that those whom a culture has reason to value most – the bearers of cultural values such as teachers, sages, elders and families – were the ones to suffer the most in the aftermath. One can argue that Ashoka’s founding ethical document is suggesting an equivalence: the loss of life and livelihood involved in a horrible war and its aftermath is analogous in scale to the violence required to sustain the daily habits of power. In war, the worthiest among us are often the most vulnerable; perhaps in daily life the most vulnerable among us, and the easiest overlooked, are more worthy of our regard than we realise.

Ashoka encouraged his bureaucrats to develop a moral responsiveness with respect to the incarcerated

At the heart of Ashoka’s ethical project is a concern to bring other beings and their possibilities into view. Consider different ways in which living beings might be excluded from our regard. For example, it is only when we see animals as entirely outside of our moral and political community that it’s possible to see them as meat. In the edicts, we find a concern with how the incarcerated, for greater or lesser periods of time, can also fall out of our consideration as fellow members of our moral community. Housed out of sight, we don’t see them, just as in a metaphorical sense we fail to see them when we treat them as less than us.

As an antidote, Ashoka encouraged his bureaucrats to develop a moral responsiveness with respect to the incarcerated. He says that if his ministers think ‘This one has a family to support,’ or ‘This one has been bewitched,’ or ‘This one is old,’ then they will see them anew, and can work to rehabilitate and reintegrate such a reconsidered prisoner in society. The challenge, Ashoka suggests, begins in our imagination: we must learn to see them entire. In fact, in the case of prisoners, refugees from war, internally displaced peoples, and animals – vulnerable beings, all – Ashoka recommends an imaginative experiment: to see them as individuals who maintain and value relationships with others of their kind, if not with us.

And that is key. The logic of Ashoka’s proscriptions on hunting, fishing and cruelty in animal husbandry in his fifth-pillar inscription can show us why. There, Ashoka suggests that living beings require a secure place in which to thrive, and that different types of places suit different types of beings (such as forests, rivers, or even husks for small-scaled life). He implies that all living beings exhibit different kinds of vulnerabilities and opportunities at various stages of life or at different times of the year (as when fish spawn only in certain lunar months, or sows are in milk). Living beings have patterns of dependency without which they would not be able to survive. By virtue of being a necessity for the flourishing of life, each context, pattern or stage of dependency acquires a moral status.

Ashoka has ethical concern flow out of a recognition of such dependencies. Human contexts of dependency are bound up with our social nature. We can treat others as fitting recipients of care when we treat them as subjects like us: as existing in social relationships, and as subjects for whom these relationships matter. To adapt the American philosopher Thomas Scanlon’s memorable phrase, goodness for Ashoka consists in what we owe to others: it consists in the ‘non-harming of living beings’ and ‘proper behaviour towards relatives, Brahmins, itinerant philosophers, respect for mother, father, elders’. In the 11th edict, Ashoka adds that goodness includes obligations to those who are socially beneath us, and to those with whom we are social equals. Thus, he says, we owe ‘respect to slaves and servants, and liberality to friends and acquaintances’.

What gets in the way of our being ethically responsive to one another? Goodness, Ashoka argued, cannot be done by one alone, nor ‘by one who is without ethical discipline’. We are not alone. There are others with whom we are connected, now and over the many generations Ashoka believed necessary for goodness to take hold. Ashoka is also thinking of the state.

He doesn’t think of the state abstractly. In a striking image in the fourth-pillar edict, officials of state are described as the clinical and parental face of an administration with which one can strike up a relationship – as one would with an intelligent nurse. Elsewhere, the state is said to exist for the sake of its subjects. The asymmetry inherent in the relationship of ruler and ruled is now conceived to indicate a debt owed by the sovereign to his people. People are said to be bound to the king as children are to a parent.

Ashoka even thought up an original reason for celebrating bureaucrats: the vocabulary and norms with which people can come to make sense of their lives in ethical ways must be made accessible to them. People need to be able to see and learn from exemplifications of ethical ideals and find them intelligible as possible ideals for themselves. This is the job of bureaucrats in Ashoka’s administration: ensuring ethical progress, or ‘growth in goodness’, to use his phrase. It is a two-fold process. In the seventh-pillar edict, he argues that it requires legislation as well as internalisation through meditation. New laws have to be made and promulgated, to be sure: but these must be accompanied by internalisation; and this presupposes moral instruction if they are to be effective. Ashoka believed it was the state that should provide the language by which a people come together in their understanding of collective ethical possibilities.

The edicts and the practices of recitation and interpretation that served to broadcast the ethical message they bore might be described as an epistemological variety of public infrastructure. But one need not rely on metaphor to see that infrastructure, too, can be an ethical concern. Ashoka’s public works include planting trees alongside roads to give shade to men and animals; funding mango groves; digging wells; building rest-houses, highways, hospitals; and even pharmacological gardens for humans and animals, as outlined in the second-rock edict and the seventh-pillar edict: ‘And wherever medical roots or fruits were not available they were caused to be imported and planted.’

Rich or poor, layperson or sage, Ashoka would have us all see that we can train to live as philosophers did

The ethical character of infrastructure comes down to this: environments, Ashoka suggests, can be made more or less conducive to flourishing, and for generations. Centuries later, the Buddhist pilgrim Faxian (337-422 CE) could still observe in Pataliputra – the cosmopolitan city that had once been the Mauryan capital – an enviable ethos concerned with public health. As for other Ashokan works, Mauryan aqueducts and irrigation techniques have recently been successfully put to work again in parched Gaya, the storied district in the heartland of the Mauryan empire where, long before, Siddhattha Gotama is said to have become the Buddha.

But recall Ashoka’s conviction: Goodness cannot be done by one alone, nor by one who is without ethical discipline. Goodness requires that individuals engage in critical self-reflection and cultivation. The discipline involves the exercise of ongoing control of one’s habits of thought, speech and action, so that feelings such as cruelty, anger, pride and jealousy – feelings Ashoka notes in the third-pillar edict – are not allowed to bring oneself and others into view in a way that interferes with moral responsiveness. There are more subtle concerns. In a freestanding edict, Ashoka had his judges consider the following hindrances to the full and just exercise of our attention: when one is in a hurry, inexpert or fatigued, one doesn’t pay attention to others and their case as one should. For early Buddhists, such factors were practically relevant. When engaging in the practice of mindfulness, for example, certain factors hinder our ability to attend to some chosen object or task. But such hindrances, Ashoka suggests, are morally relevant. They prevent other beings from fully coming into our view.

Care for the avoidance of injustice – and the control of oneself more broadly – entail habits cultivated as part of a demanding way of life. When the king claims to have made himself available to the call of justice anywhere, anytime, no matter what he was doing – whether eating, sleeping or at leisure – he was speaking as ascetics or ancient philosophers might. One might expect to hear such talk from individuals who had distanced themselves from the normal worldly life to transform themselves and so achieve freedom. Such individuals were able to devote themselves to critical self-reflection, down to their most evanescent behaviours, feelings and thoughts. Ashoka presents the revolutionary suggestion that anyone might take up their life and routines as an ascetic philosopher might and for similar reasons. One of his earliest stated ethical convictions in the so-called Minor Rock Edict I (258 BCE) was that the goal of felicity ‘can be reached even by the lowly, if devoted to morality. One must not think that only the exalted may reach this.’ Rich or poor, layperson or sage, stay-at-home or full-time renunciant, Ashoka would have us all see that we can train to live as philosophers did.

In arguing as he did for the importance of such practices of self, Ashoka had something else in mind. He thought he could put his finger on what united religious and philosophical traditions: a concern with moral psychology, taking the form of techniques by which to control oneself and a concern with inner purity. Ashoka believed that, in underscoring this, his edicts might bring into being mutual understanding, or the ‘coming together of traditions’ – and the coming together, or ‘concord of traditions’, Ashoka declared, was good.

Since around 260 BCE, Ashoka had been a Buddhist layman. By his own admission, though, he didn’t get serious about his Buddhist commitments until sometime in 259-258 BCE. At no point, however, did he allow himself or his bureaucrats to favour one tradition over another. He was a pluralist in matters of state. In the seventh edict, he tells us: ‘Beloved of the Gods … desires that all traditions should reside everywhere’; in the 12th, that ‘there should be growth in the essentials of all traditions’. In speaking of ‘all traditions’, Ashoka had in mind a connected world from Athens to Pataliputra – a world in which ethical experiments on oneself could be articulated and made mutually intelligible across ethnic, linguistic and territorial borders; by ‘growth in the essentials’, he projected a climate of mutual respect and understanding:

One should listen to and respect all doctrines professed by others. [The king] desires that all should be well-learned in the good doctrines of other traditions.

Ashoka’s pluralism involves the following acknowledgement on the part of members of traditions: the presence of many traditions is a good thing, and such acknowledgement is consistent with the aims and doctrines of each tradition: it will lead to the flourishing of each. Such principled pluralism inspired Nehru’s vision of a secular Indian state. It led him to place his hope in a new variety of politics – one that would be cosmopolitan and cooperative, valuing life and not territory, dedicated to the enhancement of freedom everywhere. Reading the way in which Ashoka was invoked by the Constituent Assembly on 22 July 1947 can make for discomfiting reading today. It is hard not to give in to either nostalgia or condescension.

Goodness can be unassuming, scaled to the unobtrusive acts of ordinary people

Could India’s reconstructed past ever have indicated her possible future? When I think of what we might make of India’s first leaders, I think of what they made of Ashoka; and I think of what Ashoka might have made of them. ‘There will be no full freedom in this country or in the world as long as a single human being is unfree,’ Nehru told the Constituent Assembly. ‘[S]tarvation, hunger, lack of clothing, lack of necessaries of life and lack of opportunity of growth for every single human being, man, woman and child’ all compromise the life of freedom. That, Nehru maintained, is the challenge before India, the ‘terrific task’, one that he, not unlike Ashoka, believed we’ll have to ever bequeath to our descendants. Why? The reason Nehru gave, sounding not a little like Ashoka, is that ‘there is no ending to that road to freedom’. Arguably, Nehru’s vision of progress never did make room for Ashoka’s conception of moral growth. Recall Ashoka’s conviction: ethical education must complement new legislation and infrastructural change. Nehru never did lay the foundation for an Indian institute of ethics, only the Institutes of Technology. He had no feel for the everydayness of goodness.

Ashoka, like Gandhi, was more sensitive to the various scales at which goodness must play out. Sometimes goodness can be unassuming, scaled to the unobtrusive acts of ordinary people when they have left the spotlight of public attention. Goodness doesn’t have to be confined to the dramatic gestures of states, nor does it need to be restricted to dramatic examples of unerring perfection. Ashoka’s first rock edict, you will recall, didn’t say that he had become vegetarian – only that he was getting there:

Only three creatures, two peacocks and a deer are killed – and the deer not always. And in time, not even these three creatures will be killed.

With this one disarming example, Ashoka began in India what Panaetius (c185-109 BCE) inaugurated in Stoic discourse: it is the ordinary person, trying and failing to be good, who deserves to be taken up as the moral exemplar. The extraordinary efforts of ordinary people matter; particularly when these are directed at new ethical possibilities that the state underwrites through legislation, education and long-term infrastructural and ecological commitment – or so Ashoka’s Inscriptions on Ethics argued.

Here, at what seems like the ending of an age, we might wonder where such an example of goodness can be found in politics today. Ashoka thought that broadcasting his ideals and his efforts at goodness mattered. He thought such goodness difficult, but not impossible. On the unending and sometimes meandering road to freedom, time will tell if he was right.