No civilised person is supposed to make bonfires of books. ‘Wherever they burn books they will also, in the end, burn human beings,’ wrote the German poet Heinrich Heine in the century before Nazism. Burning books is a sacrilegious act, and the taboo against it particularly binds writers. So what was I doing in a Somerset field lighting a match under the 32 volumes of the Encyclopædia Britannica?

In my defence, this was more of a cremation than a burning at the stake. The books were already dead, terminally rotted after years of neglect. If I had committed a crime, it was to let them get into this sorry state, not finally to put them out of their misery.

It was a long, slow ignominious end for what was once a proud, admired collection. I don’t think anyone with a regard for learning could watch them burn without being deeply pained; and being responsible for their demise piled guilt on top of the anguish. But like any funeral, this blaze was essentially about showing respect. Rather than just tossing the encyclopædias away, I wanted to take the chance to reflect on what such books have meant to their owners, and how that has changed over time. And the more I thought about it, the more ambiguous the picture became.

The most obvious insult of the burning was to all the parents who, like mine, sacrificed so much for the benefit of their children’s education. In the pre-digital world, the Encyclopædia Britannica was a very expensive investment, one that few working and lower-middle class families could afford to buy outright. In the days before easy credit, most bought theirs from door-to-door salesmen on the ‘never-never’: hire purchase payments spread weekly or monthly over years. This wasn’t done lightly. Hire purchase was usually reserved for large household expenses such as a three-piece furniture suite or fitted carpets. Spending that amount on books was a serious commitment that would have diverted resources from other desirable goods.

‘Which is more important to your child … The size of his home or the size of his mind?’

So what made parents do it? To believe that encyclopædias took pride of place in living rooms because they were valued symbols of moral self-improvement and pure learning would be hopelessly romantic. Most families who signed up to the ‘book a month payment plan’ were really buying a promise of a better life for their children, one that the advertising for the encyclopædias relentlessly reiterated. For years, this was captured in the simple three-word slogan that gave its name to a free no-obligation brochure: ‘The Britannica Advantage’.

What this advantage added up to was clear in Britannica’s newspaper and magazine advertisements. One from 1983 reads: ‘It’s no secret that your child’s success in life depends largely on the grades they get in school. That’s why you should give your child as many tools for success as possible. Especially a fine encyclopædia.’ Television advertisements peddled the same line. One from the mid-1980s shows a doughty schoolboy trudging through the rain in a yellow mac. ‘How far do your kids have to go when they need information in a hurry?’ asks the narrator. ‘I’d better get to the library before it closes!’ says the despairing kid. The voice-over continues: ‘If only he had the new Encyclopædia Britannica at home!’

No wonder so many parents dutifully cut out their brochure request forms along the dotted lines. How could they deny their children the Britannica Advantage? The message was irresistible. In one way, its power was testament to the noble aspiration many working-class families had for a better life for their kids. But in others, it was a now all-too-familiar example of the consumer culture selling unrealistic dreams for too much cash. A child’s success does depend on school grades, but these depend more on the social background and the culture of the home than any purchased learning aids. A set of encyclopædias that remains an item of furniture is not enough to give a child an edge; nor is it necessary if the household is one in which learning, inquiry and debate are all part of daily life.

The sad truth is that most families who stretched their finances to the limit for the sake of a set of encyclopædias would have been better off spending half that money or less on books with beginnings, middles and ends that children might actually read. In many homes, by sheer weight and volume, encyclopædia sets often added up to more than all the other books in the house put together. While they were the most admired volumes on the shelf, they were also the least read. Sure, every now and again someone would say: ‘Look it up in the encyclopædia,’ or you’d go searching for a fact that was eluding you. More often than not, however, you wouldn’t find it. I’m sure I wasn’t the only one who didn’t even really understand the difference and relationship between the 17-volume macropædia and the 12-volume micropædia; or the two-volume index and the one-volume propædia. Trying to find anything in there made me feel like the baffled child who asks how to spell a word and is told to look it up in the dictionary; how can you find the word if you can’t spell it in the first place? No wonder only a tiny fraction of the 44 million words in the Encyclopædia Britannica were ever read, and most of the 30,000-odd pages were never even opened. The volumes gathered dust because we literally didn’t know how to use them.

The Britannica Advantage was not only illusory, it also reflected the way in which the market economy always finds a way to turn things that are good in themselves into means to an end. In this, the marketing of the Encyclopædia Britannica was prescient. Today, families make similar financial sacrifices to get their children through university, increasingly to study courses that are either explicitly vocational or that promise improved job prospects. The key selling point for higher education is not education for education’s sake but the oft-repeated claim that graduates earn considerably more than non-graduates: an average of £12,000 a year more in the UK, and $17,000 a year more in the US. Even venerable philosophy departments such as the University of Stirling’s pointed out to prospective applicants that ‘the employability of philosophy students has increased in recent years’. Unfortunately, they do so on the basis of newspaper reports that show a complete absence of the basic critical thinking skills supposedly taught by philosophy departments.

Perhaps there was a time when encyclopædia salesmen were not just selling the dream of greater riches, but one of a richer life of the mind. Back in 1958, the high-minded question posed to potential buyers was: ‘Which is more important to your child … The size of his home or the size of his mind?’ Whether or not this was simply a cynical way of persuading parents to channel more of their money to Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., it was only in the later advertising that the material benefits of education gradually came to the fore. In rhetoric that has become almost universal, books are there to improve grades, which in turn serve the purpose of leading to more success in life. And it is no secret what is meant by ‘success’ here: better-paid jobs, larger houses, more disposable income. Books are not intrinsic parts of the good life, they are ‘tools for success’. Perhaps the Encyclopædia Britannica did once stand for the idealistic dream that, by acquiring knowledge, we might come to uplift ourselves, live better lives than those who came before us. But unless that is underpinned by a humanistic understanding of what a better life is, the dream is a shallow one of more money, higher status and shinier objects.

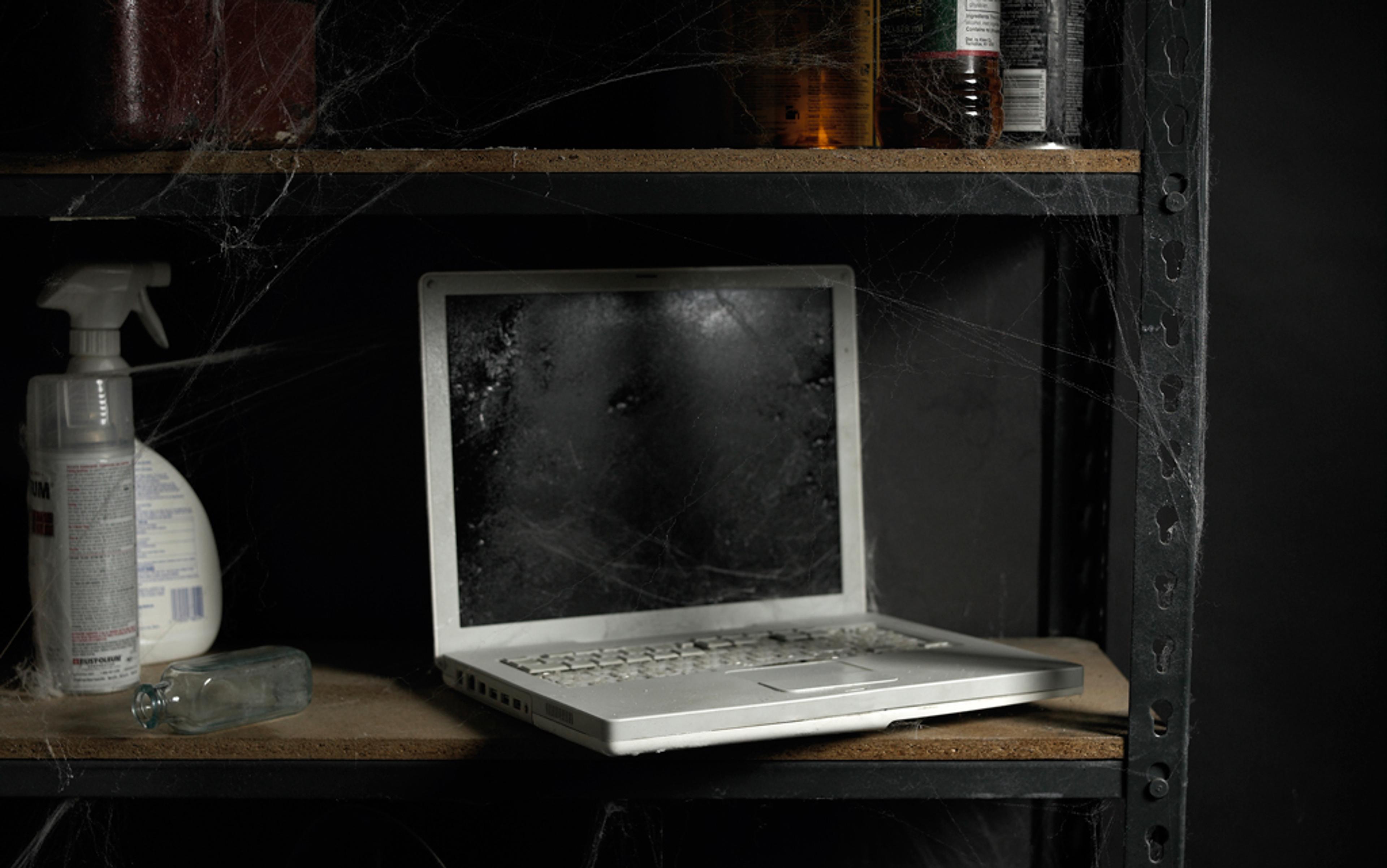

If there ever was anything to the Britannica Advantage, the internet has since eroded it. Rarely used at the best of times, an encyclopædia is hard to look up, quickly becomes outdated and has now been made redundant by information on demand. And in small flats or houses, the shelf space required by such obsolete works becomes hard to justify. That’s why I moved my set into a cellar while a new home was being found for them. But here was the surprise: such adoptive homes didn’t seem to exist. Neither schools nor libraries wanted them. Second-hand booksellers wouldn’t take them. Small ads were met with silence. Like local pubs and independent book stores, everyone professed to cherish them but increasingly few people were prepared to support them. And so the temporary accommodation became a home of years, and mould started to do its work.

As my volumes started decaying, so did the whole institution of the printed, multi-volume encyclopædia set. In 2012, Britannica bowed to the inevitable, and started phasing out the printed version. This instantly raised their scarcity value and so the final limited edition, deluxe, Renaissance-bound 32-volume set started selling for £2,495. Since then, another final final edition of the encyclopædia has come out, this one bound in Moroccan leather and available in a print run of only 10 copies (price: £9,999).

Their feel of leather-bound permanence encouraged us to forget the dynamic nature of scientific knowledge

And yet, for the purpose of ‘information in a hurry’, it is no longer necessary to pay a small fortune to acquire them. For $1.99 a month (£6.99 in the UK), you can get the entire Encyclopædia Britannica online, on your computer, tablet or phone. Anyone who cannot see that this is real progress is allowing the romance of the printed word to cloud their judgment.

In that respect, my encyclopædic blaze symbolised the benefits of creative destruction. Britannica stood for a time when access to information was limited, and largely determined by money. The magnificence of the collection was deeply connected to the fact that they were exclusive, expensively produced objects. We might well miss the smell of the leather binding, the crisp sound of flicking through their thin pages, the gravitas that the sheer 4lb weight of each volume suggested. But if what was on those pages mattered most, we must believe that these losses are more than outweighed by the freedom for anyone with an internet connection to access the same content and more at little or no cost. A world of valuable books behind the closed doors of a privileged minority cannot be preferable to one of invaluable information available through the open door of a web browser.

What is more, the end of the print encyclopædia also signals the end of ossified knowledge in authoritative texts that were revised only every decade or so. Although they went through various editions, encyclopædias belong to a time when knowledge was owned by a handful of established authorities, who decided not only what was true but what deserved to be ennobled by its inclusion. Their feel of leather-bound permanence encouraged us to forget the dynamic nature of scientific knowledge, artistic canons and economic orthodoxies. We all knew that every reference book was already out of date before it was even printed, but with no alternative, it was an uncomfortable truth we chose to ignore.

A related but more ambiguous shift has been the decline of respect for experts. It’s hard to say which is worse: an excessive deference to a small cultural elite or a hubbub of cyber-chatter in which everyone feels not only entitled to an opinion but to a grateful audience for it. Concepts such as ‘citizen journalism’, ‘open access’ and ‘crowdsourcing’ all have their merits, but it is difficult to prevent them from descending into a relativistic free-for-all. In that respect, the transition from printed reference books to the digital universe is but one example of a wider and deeper cultural transition: how do we cope with a loss of faith in absolute knowledge without descending into a subjectivism in which the only truth is the passion with which people believe? In that sense, we haven’t yet fully worked out what the demise of print encyclopædias — and all they symbolise — means for truth and knowledge. There is a philosophically coherent position between absolute certainty and absolute relativism, but it has yet to find its place in the public square.

Because so many important issues were raised by the demise of the Encyclopædia Britannica and the old world it represented, I wanted to redeem my moulding volumes by transforming them into a work of art that would embody those questions. My initial idea was to find a public space in which I could, over a weekend, meticulously shred each volume and use the resulting ribbons to make papier-mâché facsimiles of the set I had destroyed. By transforming them from functional objects to merely symbolic ones, I would arguably be making them more into themselves. Each one would then be auctioned, an experiment in valuation, to see if by their mutation they had become more or less worthless. Half would be sold for the enrichment of the artist, half for charity, all by online auction. The print encyclopædia was defeated by technology, and now the internet would be the means for its rebirth. The public could decide, by voting online, whether the charity half should go to the encyclopædia’s kin or its nemesis: to books or computers for Africa?

I still quite like the idea, although — as with other conceptual art projects — perhaps as much is achieved by describing it as by actually creating it. But I couldn’t do it anyway, because after our next house move, there was no inside space to store the books. They were put in the garden in plastic crates that turned out not be as waterproof as we had thought. When we finally opened up the boxes, we discovered sodden, stinking books covered in slimy mould. And so a more modest performance was devised. I would make a film of their destruction by fire, both a funeral pyre to mourn the positive ideals they represented, and a celebration of the good things that superseded them.

However, no matter how much I try to frame my act of bibliocide positively, I still can’t shake the feeling that I did something wrong. If any secular object deserves the status of the sacred, surely it is the book, which aside from all those practical innovations that feed, clothe, warm and heal us, is the most important human creation of all time. But technology is forcing us to reassess the value of the written word and the forms it takes. Burning books rightly remains a powerful taboo, yet the dangers of censorship have moved beyond the threat of physical destruction. More often than not, all the information we need exists somewhere. The problems we have are finding it in the ever thickening forest of data, whole swathes of which are kept behind high-security fences. Most insidious is the way in which an under-resourced media often relies on official summaries of interminable reports, distracted from the vital details by deceptive spin.

I can’t help but mourn the passing of my set of Britannicas, but I do not mourn the passing of the institution. Encyclopædias have passed their use-by-date as fitting symbols for the esteem in which we hold culture and learning. The world is changing, and books, magazines and education have to change with it. Nostalgia for obsolete publications serves us only if we use it to remind us of the things we really value, and want to take forward into our own new world.