Insomniacs rarely forget when their sleeplessness first began. For some, like the writer Margaret Drabble, it emerges with the birth of a child; for others, it’s an episode of illness or the loss of someone they love. For me, it starts at an uncle’s house in Essex. I am four or five and my uncle is telling me wonderful bedtime tales of adventures in far flung parts, narrative distractions, or perhaps rewards, designed to see off any protests against what his hands are doing under the sheets. Sleep eludes me then not only because I am disconcerted and a little afraid, but also because the stories are too good to give up.

Anxious in the dark, I would check for monsters. I sleepwalked. I began to tell stories of my own, and a gradual transformation happened. My stories started to act as guardians against the terrors of the night: so long as I was spinning stories, the dark was dumb and powerless, the monsters had no hold over me. Over the years, narrative became my night-time ally. Sleeplessness and storytelling became woven together in my mind so intricately that today the two are almost inseparable.

For me and many other insomniacs sleep is a sort of necessary evil. We are aware that we are treading on delicate ground, that our failure to sleep might any day cross over into a failure to thrive. Insomnia, we know, increases the risk of heart attacks, strokes and mental illness. Still, insomniacs remain too attached to the narrative of the day to want to let it go. Wakefulness is too enchanting, a tableau vivant fabulously embroidered with incident, plot and character. So long as one is awake, the narrative remains open, the threads of life continue to spin in more or less limitless combinations.

Being awake at night affords the insomniac the power of reimagining the day. Without the intervention of sleep, we can ignore the intimations of mortality brought nightly as the sun sets. And though it’s true that a lack of sleep can give rise to feelings of frustration and occasionally despair, insomnia is also, in its strange way, a hopeful condition, ripe with the possibility of other endings. Why shut the door on the light when our days are both fragile and finite?

The facts, as sleep scientists are increasingly discovering, are that sleep is not a shadow of wakefulness, but an independent state, busy with its own mental and physical events. The brain, we now know, uses as many calories for its processing activities by night as by day, even if those calories are put to different uses. But the events of sleep are ones that exclude our conscious selves, so they can feel as though they do not exist at all. Closing the narrative of the day by sleeping seems to stop time. It is, like sleep itself, a little death. And there lies the rub. Whatever the reality, sleep feels like a state of non-existence. And that is something many insomniacs cannot abide.

A friend recently suggested I download a mobile phone app, which purports to track brain patterns in sleep. Insomniacs tend (often unwittingly) to exaggerate their periods of wakefulness, and the friend thought it would be useful for me to know exactly how much sleep I actually get as opposed to how little I think I do. Though I appreciated her concern, the suggestion was one only a good sleeper would ever make. Apart from drawing too much attention to sleep, thus making it even more elusive, a sleep map would seem to offer a specious guide to a terra nullius whose topography might well be sketched in by science, but whose more subtle landscapes must forever remain undefined. If we were ever conscious enough to register it, we would not, by definition, be fully asleep.

There’s a freedom to the night, an unconstrained permissiveness. Under cover of darkness, anything goes

Though sleep is not a story, dreams might be. Rather more often, though, they are hints at storytelling, fragments of narrative that can, even at the time of dreaming, feel random or perhaps simply experimental. As signposts to the otherwise unknowable realm of the unconscious, dreams are instructive and useful to me as a writer but, even so, they hold none of the seductive power of being awake. Even dreams about sex, intensely pleasurable though they can be, rarely hold a candle to the real thing.

That said, I’ve had to learn to view my sleeplessness as a gift, and I’m still often unable to experience it that way. Looking back, I can see that my adult life has been ordered around my insomnia and, in some respects, limited by it. My early adult life was dominated by an unwelcome familiarity with sleep clinics and their often vaguely totalitarian-sounding ‘sleep hygiene’ routines, as well as with visits to therapists, meditation rooms and prescription-friendly GPs.

The frustrations of failing at something so basic are hardly tempered by the humbling, almost daily confirmation of the limits of my ability to control my own body. Sleep is an elemental human function at which I am, to say the least, inexpert. Being self-employed allows me to escape from the daily alarm call, but it also means that I have had to adapt to living with financial insecurity. Not having children has relieved me from what was — at the time I was considering motherhood — the terrorising prospect of having to deal with someone else’s sleepless nights as well as my own.

And so I remain childless. Relationships have sometimes been blighted, at least in their early stages, by the months it takes for me to accustom myself to having someone beside me in the bed. And then there’s the thumping head and the numbing mental fizz of the day following a sleepless night, which so often coincides with a long journey, an important interview or a deadline of some kind or other, and leads to the inevitable sense that one is never at one’s best when it is most required.

But for the most part, I have accommodated to living with my disorder. Acceptance, or perhaps just age, has altered our relationship. The battle of mutually assured destruction it once was has significantly mellowed. We have both stopped wanting to change one another and, like any long-paired couple, we’re now fully, if not always comfortably, adjusted to our life together. Which is just as well given that, whether we like it or not, fate has made us companions for life.

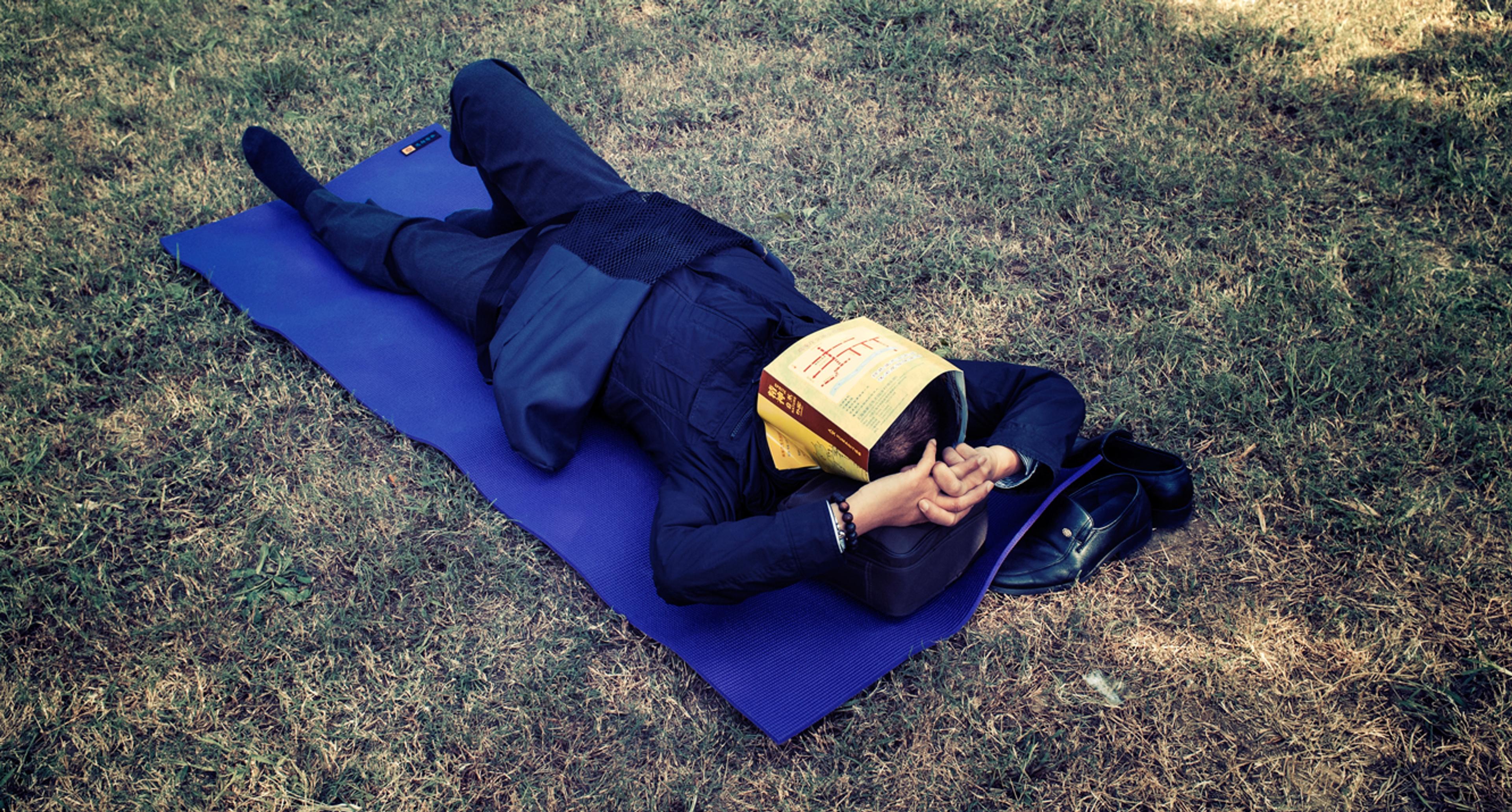

For me, insomnia’s greatest gift is the uninterrupted time and mental space it allows for reading and thinking. There’s a freedom to the night, an unconstrained permissiveness. Under cover of darkness, anything goes. Being awake in the night feels like stealing a march on time. Senses sharpen, so does the memory. The air stills and it is as though you have passed into some other, more magical dimension in which earthly rules no longer apply. There’s an exploratory feeling to the night, a special magic, as anyone who regularly stays awake through it knows. The night’s sounds, smells and sights are exclusive. The quiet lends itself to brooding, even to epiphany, at the very least to an intense focus, what Seamus Heaney calls ‘the trance’ which can be both alluring and, for creativity, highly fruitful.

My body keeps me awake until my mind has sculpted something more shapely from the day

And so I think and I read. Sometimes I get up and make toast but generally I find it most pleasurable and productive to drift in the still waters between wake and sleep, neither fully alert, nor exactly dozy. For me, the right kind of story, fiction or non-fiction, holds a real promise of sleep. At least, a firm literary resolution can mimic a narrative closure that I’m reluctant to concede in real life. I look back at day’s end, reconstructing the events of the previous 12 hours as narrative. By the time I get into my bed, the day has acquired a fully formed shape that it might have lacked as it went along.

Experience has taught me that the less satisfying the narrative of the day has been, the more likely I am to be unable to let it go. My body keeps me awake until my mind has sculpted something more shapely from the day or I am able to distract it with a more engaging narrative borrowed from the pages of a book. The vigilance of the waking hours is over but so is the magic lantern of event. No matter how glad I am to sink into unconsciousness, this always feels like a loss. Children, who are in so many ways more fully alive than us, understand this intuitively, I think. It’s a rare child who volunteers to go to bed: they too need stories, borrowed narratives to persuade them away from the thrills and puzzles of their own day.

There have been numerous experiments in which rats have been deprived of sleep. At first, sleeplessness makes them eat more, but within a few days they start to fade and die. Exactly why remains something of a mystery to scientists, though to insomniacs perhaps less so. A little bit of wakefulness goes a long way. The all-night vigil, less frequent in my life than it once was, can be numbingly, despairingly lonely, the hours endless and cheerless. At those times the sound of the first plane of the morning or the tell-tale shaking of the bed announcing the day’s first Tube train, can seem like the peal of celebratory bells.

And yet the seven- or eight-hour night, which even the best sleepers among us increasingly regard as unattainable, is nothing more than an invention of the industrial revolution. We never used to sleep this way. Two or three hundred years ago, you would go to bed for four hours directly after sundown, rise again for a period of two or three hours to write, read, pray or have sex, then settle down again for what was then known as ‘the second sleep’.

In his survey of sleep, At Day’s Close (2005), the American historian Roger Ekirch finds more than 500 literary references to the second sleep from sources as diverse as Homer, Cervantes and Dickens. It appears that this humane and creative arrangement began to be phased out in the late 17th century by the demands of the workplace and the exigencies of modern life. To return to it would be neither practical for most people nor, possibly, even desirable.

All the same, I can’t help feeling that we’re losing out. A few hours’ sleep followed by a few hours’ wakefulness, a whole night-time of remembered dreams and magic lantern shows, and the time and mental space between in which to record them. Imagine the stories we could tell in the morning.