When Winnie-the-Pooh got stuck in the doorway of Rabbit’s home after feasting on large amounts of honey, he was assisted by a great and very strange chain of being. In Ernest H Shepard’s illustration, Christopher Robin can be seen tugging on the wedged bear, followed by four rabbits, a stoat, a mouse, Piglet, three more mice, and a hedgehog. Yet another mouse scampers to join the effort. A beetle is landing behind the mouse, and aloft are two more beetles, a dragonfly and, finally, a butterfly. In Disney’s animated film, made four decades — and a hemisphere — away, the chain is foreshortened and adapted to a New World audience. Pooh remains stuck of course, and Christopher Robin still leads the effort, but lined up behind him are Kanga, Eeyore, Roo, and a Gopher! In the cartoon, the Gopher makes it clear, and Pooh reiterates it, that he ‘is not in the book’. A translocation to a new place can be unnerving: though some things remain the same, alterations are inevitable.

I recently sat with pencil sharpened and notebook at the ready, like an anthropologist in exotic terrain, to watch Disney’s The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh (1977), a feature-length collection of the earlier animated shorts. What happened, I wondered, when England’s most famous fictional bear migrated across the Atlantic and settled into an American landscape? Like Pooh, I had grown up in the British Isles and in my ripe maturity emigrated to the US. Like Pooh, I had spent much of my time out of doors. Over the back wall of our family home in southern County Dublin were mile after mile of farm fields, interspersed with shrubby hedgerow. Not quite as bucolic as Pooh’s Hundred Acre Wood, perhaps, but there, until the summer dusk drove us home, was where we largely spent our childhood vacations. Like the transplanted Pooh, the terrain in which I now dwell in the New World is hospitable enough in many ways, and yet it is also uncanny. It is not quite home. The suspicion I am investigating here is that, from an environmental perspective, there is more to this bear of ‘very little brain’ than meets the eye.

When Pooh arrived in the US, he de-hyphenated his name — perhaps a result of some tweaking at Ellis Island. Christopher Robin admirably retained his English accent, and Owl’s accent was plummy, though at times I think he hammed it up for his US audience. But Pooh, Piglet, Rabbit, Tigger, Kanga and Roo’s accents became appropriately American. The process of assimilation had begun. As often happens in cases of faunal introductions, the aliens must interact with new critters. The Gopher — a small burrowing rodent endemic to North America, enterprising and mercantile — worked out a quote for removing the wedged Pooh from Rabbit’s door. Gopher costed his hourly rate, at overtime, with 10 per cent added, and assessed how much explosive might be needed for the job. No, we are not in England anymore!

Despite all this, much in the film survives largely unchanged from the books. Scenes often start or end with reproductions of Shepard’s drawings taken from the original books, and the stories are rather faithfully retold. I would have preferred that Disney ended The Many Adventures with AA Milne’s sentence: ‘But wherever they go, and whatever happens to them on the way, in that enchanted place on the top of the Forest, a little boy and his Bear will always be playing.’ In Disney’s version, a Bear alone awaits a boy’s return. Now, that’s depressing.

Unlike most exiles, Pooh seems to have made a rather easy transition to the New World and in fact he and his friends seem to have travelled from England with their entire ecological entourage. In other words, home travelled with them. The trees, the grasses, the features in the landscape are all the same. Sand pits, bridges, even their furniture came, too. Unlike Pooh, who emigrated with Disney’s help, most immigrants do not have the luxury of travelling with their physical landscape (although there’s a long history of immigrants reshaping the land in the image of home). Most of us find ourselves distant and dislocated from all that reminds us of home. And this is true even for those who do not migrate, for adulthood is its own form of exile, in time if not in space.

One spring afternoon in the early years of this century, I took a stroll through the East Woods at the Morton Arboretum near Lisle, Illinois. The trees were still leafless and the light was very fierce, so much so that I shielded my eyes with my hand, as if I was saluting my companion, Christopher Dunn, at that time the Arboretum’s director of research. We were admiring the ecological restoration work that had been accomplished in the woodland over the years that I had been visiting. Dominated by oaks and sugar maples, the East Woods is about 1,100 acres, a sixth of the size of Ashdown Forest in Sussex, England, where the Pooh stories are set. In fact, the part in which we rambled was about the same dimensions as that part of the Forest around Owl’s house known to Pooh and his friends as the Hundred Acre Wood.

Inside the house, Pooh is just a stuffed animal being dragged along by a cartoon boy; outside, all comes to life

Here and there between the trees, we could see clumps of green where European buckthorn, an invasive shrub, was leafing out, taking advantage of the early spring light before other vegetation had emerged from its winter quiescence. On my early visits, the East Woods had been heavily invaded by this aggressive exotic Old World shrub which, though infrequently found in its native range, has become one of the major impediments to conservation efforts in Midwestern woodlands. Through active management, the buckthorn population in the East Woods had now been markedly diminished.

Both Christopher and I are Old World transplants (Christopher is a Scot), but unlike buckthorn, which has been in the region since the mid-1800s, we are very recent arrivals: he as a teenager and I when a little over 30. During our walk, we stopped at a point where we could look over the terrain and admire the fidelity with which the restoration work has returned it to the structure of a pre-settlement Midwestern woodland. Here we turned to each other, and — simultaneously it seems — both had the same thought: ‘There is something not quite right about this.’ In a nostalgic moment, both of us recalled the woodlands of Ireland and Scotland, especially the wilder places that Christopher and I both preferred: darker, more tightly packed woods on craggier terrain than is usually the case in this flatter part of the world. We were, for a moment at least, contrasting the East Woods not with its healthy ancestral state, freed from the injurious impacts of the past century, but with the woodlands of our personal memories, against which any woodland might seem like a collection of so many living sticks.

The fact is, we are living in times of great transplantation. About 1.5 per cent of the US population moves between the major regions every year: about five or six per cent move across county lines. Internationally, the numbers of people crossing borders is staggering. For instance, if all those who migrated internationally in 2010 (about 216 million people) converged on an uninhabited region (say Antarctica) it would make that country the fifth most populous country on Earth. Accompanying the flow of goods, services and people is a great biological interchange where species that were formerly restricted to one biogeographical zone are transported, either deliberately or unintentionally, to areas outside their native range. Christopher and I, standing in our hundred acre woods, personified these frenzied exchanges. Old-World islanders in the US Midwest, we were discussing a European botanical rarity that was now thriving in Chicago woodland.

Since a person’s attunement towards nature is most often determined by youthful encounters with place, that which is most delightful to us in nature as adults is that which we remember from our youth. Thus, the landscapes of our adulthood, whether we have moved 300 miles or 3,000, tend to remain somewhat unfamiliar to us and, as a consequence, difficult to understand, much less to love. This is one of the neglected consequences of the great transplantation: I call it the Uncanny Landscape Hypothesis. Does this make it difficult for us to care for the landscapes in which we find ourselves, whether pristine, managed, or restored? Perhaps more positively, do we need new tools — tools of initiation, imagination, and empathy — to fit into a landscape that is new to us?

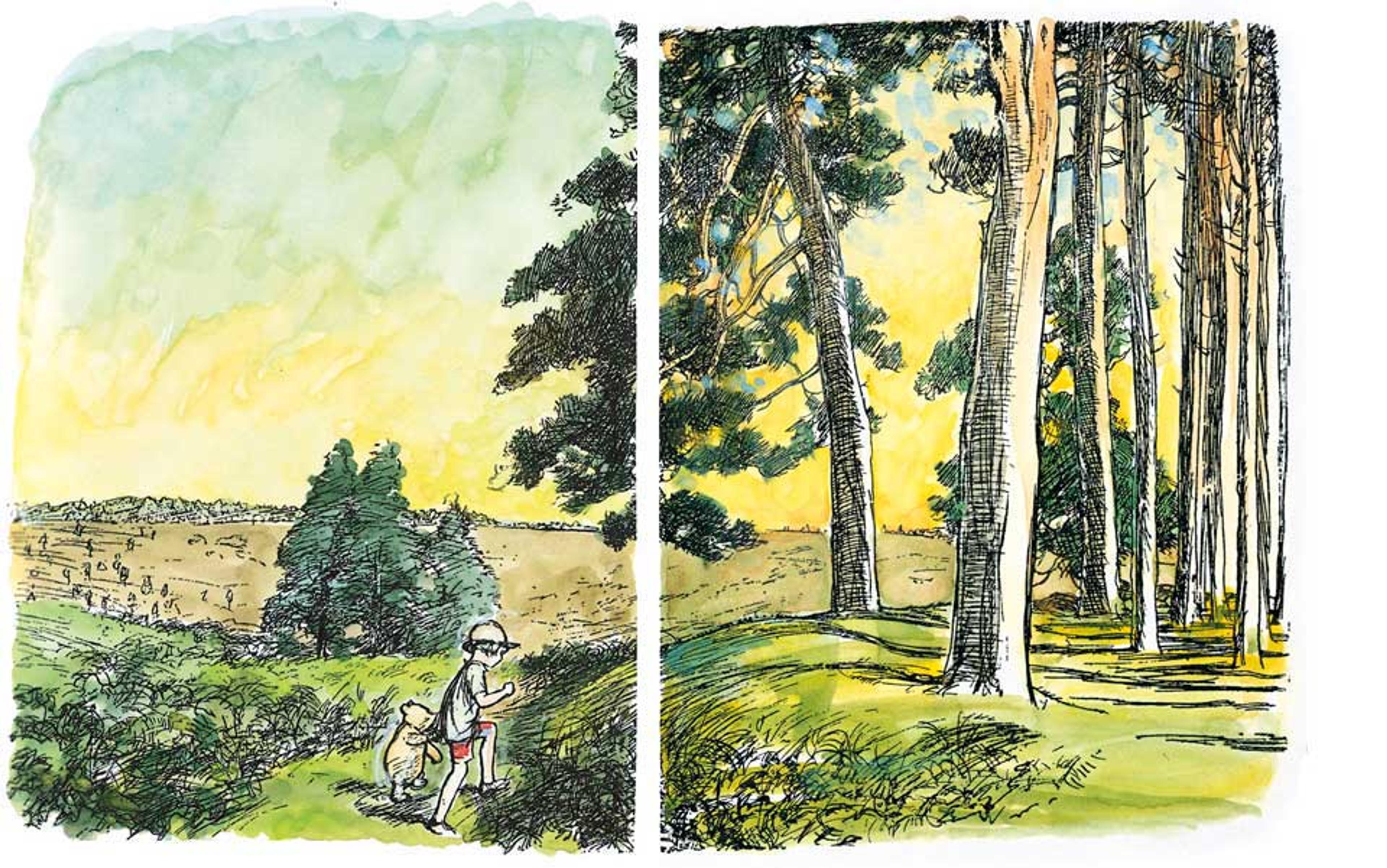

That we can read Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh (1926) and Disney’s later adaptations through an ecological lens at all is a testament to the fidelity with which both Milne and Shepard, his illustrator, reproduced the landscapes of Ashdown Forest in Sussex in which the original stories were set. The Pooh stories captured a cultural landscape at a time when its human and natural elements were felicitously combined, as well as the special, intimate relationship between a child and that landscape. It is very clear that the boy (based on Christopher Milne, the author’s son) loved his bear, and loved the landscape in which they had their escapades.

The connection between children and nature has taken on considerable urgency in recent years. Evidence is accumulating that access to outdoor experiences is vital for children’s physical and mental health. The absence of such opportunities manifests itself in ‘Nature Deficit Disorder’, a term coined by the American writer Richard Louv in Last Child in the Woods (2005). Viewed from this perspective, Winnie-the-Pooh and the biographical elements the book imports from Christopher Milne’s life are an informative case study of the connections between a child and a landscape. Inside the house, Pooh is just a stuffed animal being dragged along by a cartoon boy; outside, all comes to life.

In his autobiography The Enchanted Places (1974), Christopher Milne recalled his real adventures in the Sussex countryside surrounding Cotchford Farm, which his family bought in 1925 when Christopher was four. They spent their weekends and holidays there and, in the company of his father or, more often, his nanny, Christopher made progressively deeper forays from garden to farmland and into the woodland and forest beyond, always on foot and, as he got older, on his own. Over time, his walks got longer and his intimacy with landscape grew. He remembers, many years later, what it was like to be a child lost in nature:

I would go down to the river and find a quiet place, secluded, hidden … and sit there for hours, watching the water as it gently twisted and eddied past me. Then perhaps I would see something: an eel wiggling its way upstream; a grass snake with just its black head showing above the surface, moving gently from side to side; damsel flies, their wings making a dry whispering sound as they came to investigate me; the plop of a water vole, and if you looked quickly you might see it running underwater along the river bed; a shy moorhen, a noisy mallard, a flashing kingfisher, whistling urgently.

As Christopher’s ambit broadened, he encountered the locations that his father would later write into his books: Pooh Sticks Bridge was on the way into Posingford Wood near Cotchford. Further along the road is Ashford Forest, the forest of the books. From Gill’s Lap (Galleons Lap), one could walk down into a valley and up again towards some distant trees. This is the Hundred Acre Wood (in reality, a Five Hundred Acre Wood). Unlike the more open landscape of Posingford, this wood is darker and in it grew ancient beech trees. You might recall from the books that Piglet lived in one of these beech trees. The Hundred Acre wood was also home to Owl. Some of these trees were felled during the Second World War, to Christopher Milne’s regret, because, as he wrote, ‘among them was a tree I was particularly fond of’.

Childhood might be the time when connection with place is fiercest

Memories of the natural splendours surrounding his childhood home sustained Christopher Milne through his military service in the Second World War. However, he destroyed all of his early efforts to write about that enchanted place. It would be 30 years before he could do so and, if that late account celebrates his early connection with nature, it also provides a cautionary tale. Christopher Milne famously resented the Christopher Robin of his father’s tales, and the tensions this caused with his father. The perennial child ‘Christopher Robin’ outshone the adult ‘Christopher Milne’. In later years, when Christopher Milne was asked if it saddened him not to have his toys with him anymore (they now live in a glass case at the New York Public Library), he responded: ‘Not really … I like to have around me the things I like today, not the things I once liked many years ago.’ In ending The House at Pooh Corner (1929) as he did, AA Milne anticipated the problem by leaving the little boy and his bear at play in their enchanted place. Christopher Robin, the boy, remained perennially on the hill, even after Christopher Milne, the man, had long vacated the spot.

Childhood might be the time when connection with place is fiercest. As we grow up, the adult and the quotidian envelop us. Often, we set aside more than just our childish things: we vacate our childhood world. It was perhaps inevitable, given the nature of the story he had to tell, that Christopher Milne’s autobiography returned to the world of Pooh and the childhood world of Christopher Robin. There is no sense in The Enchanted Places of Christopher Milne’s adult connection with nature or place. In one passage in his book, he recalled in great detail where different flowers were found near Cotchford: the ash plantations for orchids; cowslips at the top of a field; the large wood for bluebells. He and Nanny would pick basketsful of flowers. After mentioning this, he wrote what seems to me the most bittersweet line of his memoir: ‘And it was here … I would find that splendour in the grass, that glory in the flower, that today I find no more.’ No, there is no going home again, nor can the man become the boy.

We might have a rich literary archive on the human connection with place, but serious scholarly investigation of the psychology of this relationship and how it might change during a lifetime has only begun in the last few decades. The full panoply of associated psychological attributes are only now being excavated — under the banners of EO Wilson’s Biophilia hypothesis, Yi-Fu Tuan’s notion of Topophilia (and Gaston Bachelard’s phenomenological account of Topophilia that predates this), Jay Appleton’s symbolic analysis of landscapes, Louv’s Nature Deficit Disorder, and a variety of ecopsychological investigations. Many of these trace the roots to the pioneering work of the environmentalist and counter-culture historian Theodore Roszak.

All of these theoretical accounts ask whether we have genetic predispositions to certain landscapes, how our cultural identity with place is formed, and so on. However, according to the environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht, professor of sustainability at Murdoch University in Western Australia, we do not yet have an adequate vocabulary to address our ‘psychoterric’ states — or how the state of the Earth relates to our states of mind. To balance the negative psychological state of ‘nostalgia’, a couple of years ago Albrecht proposed ‘endemophilia’ (the sense of being truly at home within one’s place and culture — or ‘homewellness’). To balance the term ‘topophilia’, a love of place, Albrecht opposes ‘solastalgia’ — the desolate feeling associated with the chronic decline of a homescape. Solastalgia names the emotions we have at the loss of species and habitats through climate change and other environmental changes. We should all expect a lot more of it.

Even if the world stood still, we would still spin away from it

We could say, then, that the tales of Pooh and his friends are a celebration of ‘endemophilia’, a deep at-homeness in place and time. On the other hand, Christopher Milne’s memoir has elements of solastalgia, as in the pain he associates with the loss of those beech trees. Indeed, he warned the readers of The Enchanted Places that, though they could try to follow his map of the Cotchford terrain, they might not be able to do so, as the landscape could have changed. Solastalgia could be the ruling mood of our age.

But there is another sadness recorded in Christopher Milne’s story, a sadness that most of us experience, I expect: the loss of connection with place, especially a natural one, that happens as we grow older. I propose, in the spirit of Albrecht, to call this ‘toponesia’ (from the Greek topos, place, and amnesia, loss of memory). Even if the world stood still, we would still spin away from it, dragged into the orbit of our private economies and that series of mischiefs that we call our adult life. These psychological factors associated with Winnie-the-Pooh — its nostalgia, solastalgia and toponesia — combine to make the stories a surprisingly powerful meditation on place, as much as a source of simple pleasure.

The Winnie-the-Pooh stories express the powerful and intimate connections that we form as children, not only with our toys, which we imbue with life, but also with place, which serves as both cradle and companion. A larger inspection of the books (and the real life of their central character) manifests both the delights and the discomfiting aspects of our relationship with place. Connections with nature that many of us nourish in memory are hard to retain in adulthood. An inspection of Christopher Milne’s story brings to mind that we grow up and we change, as do landscapes, as do our relationships. We leave our childhood places behind us, sometimes literally, by thousands of miles, traversing several biomes before alighting like storm-tossed petrels in deeply unfamiliar territory.

We think we need to inculcate in our children a love of the wild, but I suspect we misunderstand the direction in which instruction must flow

Discovering how to develop an affiliation for new places might be the major environmental task of our age. Even those who do not move at all will find themselves in places that feel new, as habitat damage and climate change take effect. And, if we do leave, we need to learn to love the places in which we find ourselves.

What tools are available to us? AA Milne’s method was the vicarious: as Christopher Milne wrote in his memoir, ‘My father who had derived such happiness from his childhood, found in me the companion with whom he could return there.’ We can see the world with our children’s eyes. Recently, I saw a father leaning over his child who was enraptured by a bird hopping on a city sidewalk. Mimicking his child’s enthusiasm, he whispered in his best David Attenborough voice, ‘I think it’s a sparrow.’ We think we need to inculcate in our children a love of the wild, but I suspect we misunderstand the direction in which instruction must flow.

But there are other ways, I think, in which we could gain as adults a love for those places, uncanny though they might be, in which we find ourselves newly arrived, or in which old certainties are disrupted. My model in this regard is Tim Robinson, an English writer, who in the 1970s showed up on the west coast of Ireland. Over the subsequent decades, by dint of his map-making, his writing (about Aran and Connemara), and his scrupulous attention to people and place, Robinson has become almost synonymous with the West of Ireland. His basic methodology is walking and listening: just as Christopher Milne and his imaginary companions before him were wont to do. If we are to regain intimacy with this place, this Earth, we might have to take up again those ancient and revolutionary tools, walking and listening, listening and walking.