In the drawer of her bedside table, Julie maintains an archive of lust. Here are the naked Polaroids she slipped in between her husband’s business papers, explicit notes once left on mirrors, Anaïs Nin, a riding crop. Come evening, Julie used to watch her husband’s movements from across the room, eager for the moment when dinner was done, the kids were asleep and all other intrusions to pleasure had been dismissed. When strangers asked if they were newlyweds, Julie loved responding that they had been married for years, and believed that they were inured to the frazzled disinterest that had settled over the bedrooms of her friends. ‘You always hear how attraction fades with time – the honeymoon period comes to an end. But I always thought that was other people’s misfortune,’ she says.

So when her longing began to dull, Julie struggled to discern what was going on. She blamed the stress of work, the second child, her busy and travel-heavy schedule, the effect of changing seasons, until she had run down the available excuses, and still found she would rather go for a jog on Sunday mornings than linger in bed.

These days, Julie says it feels ‘like suffocating’ to endure her husband’s affections. ‘I’m supposed to get home from working all day, play with the kids, cook dinner, talk about entertaining things, and then crawl into bed and rather than sleep perform some sexual highwire act. How is that possible? That sounds like hell, honestly.’

Julie still loves her husband. What’s more, her life – from the dog, to the kids, to the mortgaged house – is built around their partnership. She doesn’t want to end her marriage, but in the absence of desire she feels like a ‘miserable fraud’.

‘I never imagined I would ever be in the self-help section in the book store,’ she says, but now her bedside table heaves with such titles as Sex Again (2012) by Jill Blakeway: ‘Despite what you see on movies and TV, Americans have less sex than people in any other country’; Rekindling Desire (2014) by Barry and Emily McCarthy: ‘Is sex more work than play in your marriage? Do you schedule it in like a dentist appointment?’; Wanting Sex Again (2012) by Laurie Watson: ‘If you feel like sex just isn’t worth the effort, you’re not alone’; and No More Headaches (2009) by Juli Slattery.

‘It’s just so depressing,’ she says. ‘There’s this expectation to be hot all the time – even for a 40-year-old woman – and then this reality where you’re bored and tired and don’t want to do it.’

Survey upon survey confirms Julie’s impressions, delivering up the conclusion that for many women sex tends toward numbed complacency rather than a hunger to be sated. The generalised loss of sexual interest, known in medical terms as hypoactive sexual desire, is the most common sexual complaint among women of all ages. To believe some of the numbers – 16 per cent of British women experience a lack of sexual desire; 43 per cent of American women are affected by female sexual dysfunction; 10 to 50 per cent of women globally report having too little desire – is to confront the idea that we are in the midst of a veritable crisis of libido.

Today a boisterous debate exists over whether this is merely a product of high – perhaps over-reaching – expectations. Never has the public sphere been so saturated in women’s sexual potential. Billboards, magazines, television all proclaim that healthy women are readily climactic, amorously creative and hungry for sex. What might strike us as liberating, a welcome change from earlier visions of apron-clad passivity, can also become an unnerving source of pressure. ‘Women are coming forward talking about wanting their desire back to the way it was, or better than it was,’ says Cynthia Graham, a psychologist at the University of Southampton and the editor of The Journal of Sex Research. ‘But they are often encouraged to aim for unrealistic expectations and to believe their desire should be unchanging regardless of age or life circumstances.’

Others contend that we are, indeed, in the midst of a creeping epidemic. Once assumed to be an organic feature of women, low desire is increasingly seen as a major impediment to quality of life, and one deserving of medical attention. Moreover, researchers at the University of Pavia in Italy in 2010 found ‘a higher percentage of women with low sexual desire feel frustrated, concerned, unhappy, disappointed, hopeless, troubled, ashamed, and bitter, compared with women with normal desire’.

To make matters worse, according to Anita Clayton, a psychiatrist at the University of Virginia, most women don’t delve into the causes of their waning desire, but settle instead for a sexless norm. She writes in Satisfaction (2007):

You erode your capacity for intimacy and eventually become estranged from both your sensual self and your partner. The erosion is so gradual, you don’t realise it’s happening until the damage is done and you’re shivering at the bottom of a chasm, alone and untouched, wondering how you got there.

Fearful of this end, Julie sought medical help, taking a long and dispiriting tour of conflicting advice (‘Your experiences place you in a near majority of women, but your disinterest in sex isn’t normal’), ineffectual treatments (men’s testosterone cream, antidepressants, marital counselling) and dashed hopes (‘Each time I tried out a new therapy, I told myself it was going to get better’).

Julie is hardly alone. Instead, she counts among a consumer population of millions that pharmaceutical firms are now trying to capture in their efforts to fix the problem of desire. But what exactly are they trying to treat? A physical ailment? A relationship problem? An inevitable decline? Could low desire be a correlate of age, a result of professional stress, a clear outlier on the sexual-health spectrum or a culturally induced state of mind?

For drug makers, these questions pose more than a philosophical quandary. It is only by proving that low desire and its favoured tool of measurement – libido – are diagnosable, medical problems that new drugs can be approved.

The task has been herculean, and fraught with confusion. ‘Some of the statistics that get circulated are based on very badly designed studies,’ says Katherine Angel, a researcher on the history and philosophy of science and former fellow at the Wellcome Trust in London. As a result, it’s possible to interpret ‘the presence of fluctuating levels of sexual desire as indications of a medical problem, rather than natural fluctuation over time’.

That hasn’t stopped big pharma from entering the fray. In the case of women’s libido, the industry has spent years in hot pursuit of the condition and its chemical cure, a female analog to the blockbuster drug Viagra. Yet the more scientists try to hone in on the nature of desire, and the more they try to bottle or amplify it, the more elusive it becomes.

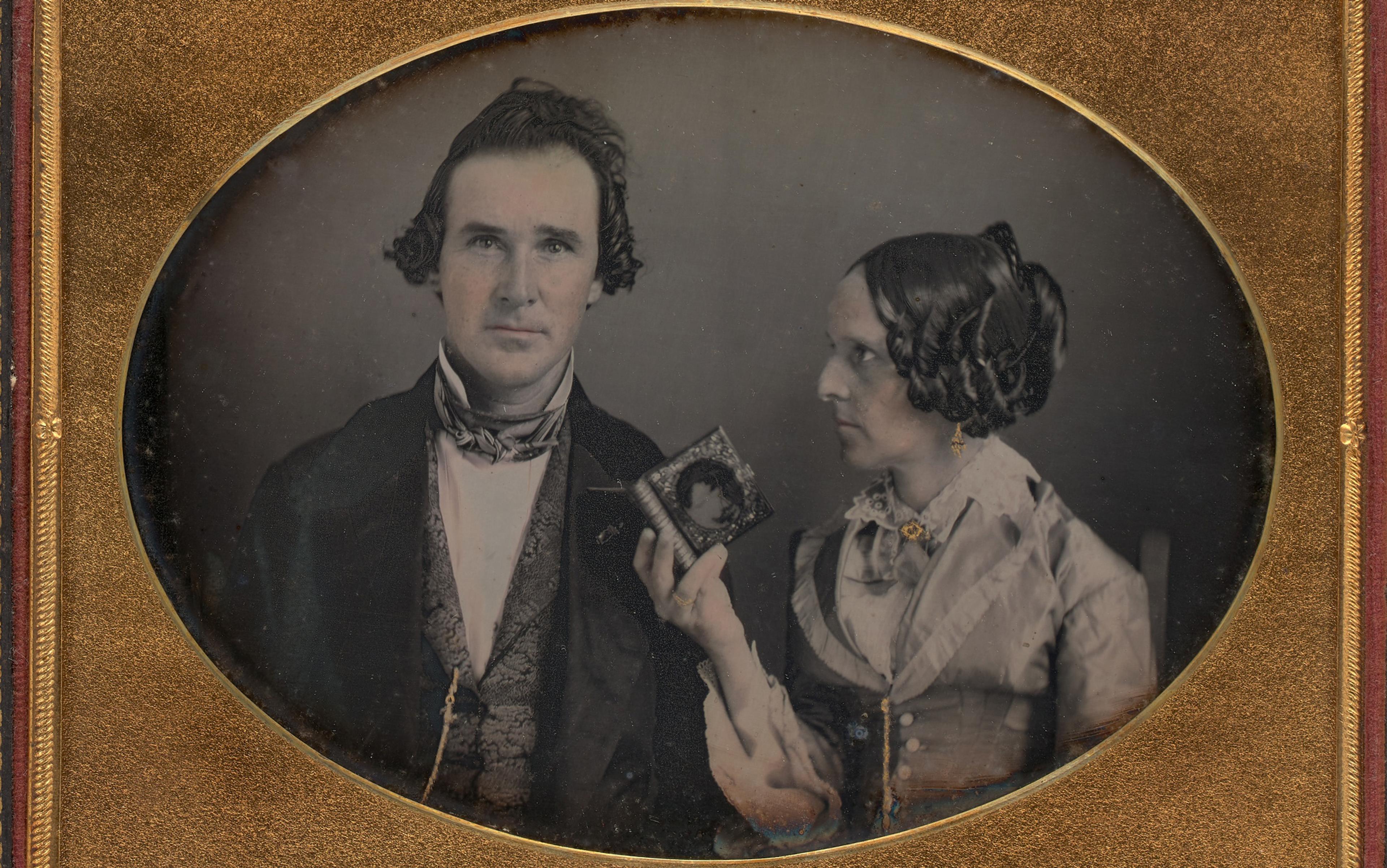

The idea that women could suffer from low desire and benefit from medical intervention reflects a major social shift. Looking back 150 years, it would be hard to conceive that doctors would be concerned with too little desire. The Victorian era is notorious for its desexualised treatment of women. Upheld as moral counterweights to men, women were thought to be sexually passive, untroubled by lust.

Yet another Victorian idea, the notion that love must constitute the centre of marriage, has amplified anxiety over lost desire today. Breaking with a long tradition of unions brokered chiefly for economic and social advantage, the Victorians privileged romantic affection between husband and wife. In the 20th century, this idea expanded to encompass sensual intimacy, and reciprocal pleasure was seen as the key to strong marriages – and the greater good.

The turn toward sensual reciprocity made partnerships more democratic, and couples were meant to provide each other with sexual, spiritual, emotional and social fulfillment. But these gains introduced new stressors, says the family historian Stephanie Coontz of Evergreen State College in Washington State. ‘New expectations were piled on to marriage – many of which were good,’ she says, ‘but they occurred in tandem with new pressures, sex among them, as well as diminished expectations for social life outside of marriage.’

Ellis argued that ‘frigidity’ or ‘sexual anesthesia’ was a response shaped by social distortions that both could and should be overcome

As social commentators in the first half of the 20th century doled out advice about the importance of sexual satisfaction in marriage, many women reported not enjoying sex as much or as often as their partners. Disorders, diseases and definitions of ‘normal’ track culture’s turns, and it was in this climate of early sexual revolution that sexology began to mature as a field of scientific inquiry. The British pioneer in the discipline, Henry Havelock Ellis, worked across the turn of the 20th century. He maintained that for men and women sex was a natural act, governed by biological urges. Ellis did not believe that women’s disinterest in sex was a natural state, but rather argued that ‘frigidity’ or ‘sexual anesthesia’ was a response shaped by social distortions that both could and should be overcome. In short, women’s low desire wasn’t a matter of biological engineering but rather an outcome of oppressive conditioning.

Nonetheless, the notion of female frigidity spread like wildfire in the decades that followed. Concerns over women’s lack of sexual desire grew so pervasive that in 1950 an article in The Journal of the American Medical Association led with the claim: ‘Frigidity is one of the most common problems in gynaecology. Gynaecologists and psychologists, especially, are aware that perhaps 75 per cent of all women derive little or no pleasure from the sexual act.’

Despite the size of the problem, by mid-century, researchers did not deem it hopeless. Following the work of William Masters and Virginia Johnson in the 1960s and ’70s, sexual dysfunction – the term that came to replace frigidity (just as erectile dysfunction would later banish ‘impotence’) – was viewed largely as a technical issue, and one that could be resolved through a proper education in physiology and technique. Their most lasting contribution has been the ‘human sexual response cycle’ – a linear model of sexual response from excitement to repose based on their lab observations of hundreds of couples, which they believed held largely consistent for men and women.

While Masters and Johnson attended to problems of orgasm and pain, they failed to note disorders of desire. Attention there emerged later in the 1970s in the work of the New York-based sex therapist Helen Singer Kaplan, who argued that Masters and Johnson dwelled on sexual function at the expense of the psychological, emotional and cognitive factors that shape behaviour. Sexual desire, Kaplan said, was a central need like hunger or thirst; low desire in women was not normal, but a natural expression ‘gone awry’. Kaplan, who opened the first sex therapy clinic in the US, wrote extensively on the treatment of sexual dysfunctions and introduced a new ailment into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual in 1980: ‘inhibited sexual desire’.

The new view of desire evolved over the decades that saw feminism flourish and brought women the Pill – and with it a confounding mix of sexual liberation and sexual disappointment. Although freed from reproductive worries, women continued to report dissatisfaction with sex, leading some to theorise that women’s desire took on a different shape from men’s, and that the Masters and Johnson linear model of lust and arousal was biased toward male experience.

In 2002, Rosemary Basson, a psychiatrist at the University of British Columbia, put forth an alternative theory. Moving away from the idea that desire occurs as a spontaneous precursor to sexual activity, she suggested that other incentives, such as craving intimacy and connection, can lead women to engage in sex. But this idea, too, has generated a host of questions around the biological differences between men and women, and whether women’s desire for emotional closeness is an organic drive, a social impulse or a kind of complacency.

Despite all the fascinating theories of female desire, nothing has generated more excitement than the prospect of an easy pill fix. The introduction of Viagra to the consumer market in 1998 brought about a radical reinterpretation of bedroom life. From an unknowable, even transcendent act, sex was suddenly – and publicly – reduced to its most mechanical elements. If, as Viagra implied, male desire was essentially an act of hydraulics in which blood flow was increased to sexual organs, mustn’t there be a similar mechanism for women?

Days after Viagra’s release, The New York Times Magazine ran an article asking whether the tablets might also help women. The piece featured Irwin Goldstein, then a urologist at the Boston University School of Medicine, who served as the principal investigator for the Pfizer-funded research that introduced Viagra to the world. At the time, he was also experimenting with using the medicine on women on the theory that improving blood circulation might improve lubrication and thus facilitate libido. Goldstein maintained that men and women were physiologically similar, and that the tissue of the penis and clitoris was effectively the same. He told the Times that female sexual dysfunction was, like men’s, a matter of poor circulation and ‘in essence a vascular disease’.

The media buzz notwithstanding, study upon study failed to prove Viagra had a real impact on female experiences of desire and pleasure, and Pfizer gave up on clinical trials in 2004. But desire was already undergoing another definitional makeover. Rather than being a matter of blood flow to the genitals, desire was placed in the crosshairs of hormonal balance, specifically ‘androgen insufficiency’ or testosterone deficiency. The men’s medical market had for years been full of testosterone-enhancing gels, creams, patches and even injections, administered on the theory that low levels of the sex hormone contributed to diminished sex drive, accompanied by weaker erections, lowered sperm count, depressed mood and physical sluggishness. Like men’s, women’s levels of testosterone decline with age, and scientists speculate that falling counts might contribute to diminished desire. As a result, medical doctors routinely prescribe men’s testosterone therapies to women with sexual dysfunction, and pharmaceutical firms are busily experimenting with androgen-boosting treatments for women.

Desire might not be so much a matter of turning on, but rather learning to turn off the quotidian noise

Goldstein was again at the fore of this new turn, furthering a hormonal understanding of women’s sexual function. He is quoted at a 2000 conference as saying: ‘For hundreds of years, women have had low levels of testosterone and we’re only just seeing this now. So, the psychological is important and all, but we’ve got to get women up to normal levels!’

Just how much testosterone affects women’s libidos remains a matter of debate. While the efficacy of testosterone therapies in men is typically assessed through physiological markers, the research on women tends to rely on self-reports of mood and sexual interest, preserving the assumed rift that assigns sexuality to men’s bodies and to women’s minds.

More than a decade later, Goldstein says he continues to be ‘frustrated by the lack of treatment options available to women’. While men have a number of ‘impressive pharmaceuticals’ at their disposal – and as a result are experiencing new levels of mid- to later-life potency – doctors often attempt to placate women with the advice to eat chocolate, drink wine or reduce stress levels. ‘We can’t intervene on one side of a partnership and not the other,’ he says.

The quest for equivalence might be one reason the treatments remained unsuccessful. To date, men’s medicines do not target desire. Erectile dysfunction drugs and testosterone therapies intervene on a mechanical level, with the underlying assumption that if the flesh is able, the mind is willing. But efforts targeting women’s physiology have repeatedly missed the mark.

Aiming to target women specifically, Cindy Whitehead, the CEO of the pharmaceutical startup Sprout, is involved in yet another turn in defining women’s sexual desire. In August 2015, her company gained US Food and Drug Administration approval for its drug flibanserin, which will be marketed under the name Addyi. Though media has been quick to call the agent a ‘female Viagra’, flibanserin does not affect blood flow, but rather acts on neurotransmitters in the brain. The compound is among a number of recent entrants into the race to develop a female desire drug that intervenes in the mind.

In their focus on neurological balance, these drugs signal a move away from looking at desire as a matter of physiological cues and toward a murkier prelude in the depths of the psyche. Stephen Stahl, a psychiatrist at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine who has studied flibanserin, says the balance of the neurotransmitters dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin plays an important role in regulating women’s sexual desire. According to Stahl: ‘In hypoactive sexual desire disorder, there’s a theory that what is wrong is that there are circuits that are inhibited, and women can’t turn off distracting thoughts and images. The brain organises planning over pleasure, but it can get stuck and doesn’t allow pleasure to flow through.’ In other words, desire might not be so much a matter of turning on, but rather learning to turn off the quotidian noise.

In this most recent scientific appraisal, desire lies at the mercy of everyday demands, present but unduly hushed by the stressors of modern life. It makes one wonder whether the researcher and pharmacologist Adriane Fugh-Berman of Georgetown University could be right: ‘We are medicalising a condition for which medication is not the best treatment,’ she says. Instead of changing our circumstances ‘like demanding help for work and childcare and reducing stress’, we have created a drug.

The psychologist Leonore Tiefer, an expert in sexuality at the New York University School of Medicine, similarly deplores what she describes as the ‘disease-mongering trends’ of women’s sexual health. Her campaign, called the New View, counters claims that low desire is a form of pathology, exposing ‘biased research and promotional methods that serve corporate profit rather than people’s pleasure and satisfaction’. According to the campaign’s manifesto: ‘The infusion of industry funding into sex research and the incessant media publicity about “breakthrough” treatments have put physical problems in the spotlight and isolated them from broader contexts. Factors that are far more often sources of women’s sexual complaints – relational and cultural conflicts, for example, or sexual ignorance or fear – are downplayed and dismissed.’

The multifaceted nature of desire – spanning biological drive, cognitive beliefs, the right time and place, and sheer motivation for intimacy – might well escape the quantifiable parameters of health and the scope of any one treatment. For some, a narrow medical diagnosis of low desire could respond to a molecular cure. But desire, much like love, contains an aspect of the unknowable – easy to strike and easy to take flight, nurtured perhaps by the persistent gulfs that exist between ourselves.

In an infamous cartoon in The New Yorker in 2001, one woman confides to a friend over drinks: ‘I was on hormone replacement for two years before I realised what I really needed was Steve replacement.’ Medicine has been reluctant to engage the question of just how much monogamy and long-term togetherness affect sexual function and desire, and the ‘Steve’ problem remains an issue that is tacitly acknowledged and yet under-discussed. To return to Julie’s growing pile of self-help titles, the books all promise to return, revive, restore without really getting down to the brass tacks of why desire extinguished in the first place. As Julie notes, the honeymoon grinds to an end, but the issues leading there are complex. In short supply is attention to the way mind and body react to social structures such as popular media, faith and marriage.

To develop drugs to boost libido is like ‘giving antibiotics to pigs because of the shit they’re standing in’

The American psychologist Christopher Ryan argues that the institution of modern marriage – meaning an exclusive couple bound by romantic love – is antithetical to long-term excitement. Ryan is best known for Sex at Dawn (2010), a book authored with his wife Cacilda Jethá, that makes the case that sexual monogamy is deeply at odds with human nature. He is among a growing number of researchers suggesting that the rift between women’s purportedly limitless sexual potential and their dulled actuality might owe to the circumstances of intimacy. Accordingly, the conjugal bed is not only the scene of dwindling desire, but its fundamental cause. The elements that strengthen love – reciprocity, closeness, emotional security – can be the very things that smother lust. While love angles toward intimacy, desire flourishes across a distance.

To Ryan, low desire is not the ailment, but rather a symptom of an ‘all-encompassing problem’ spanning the burdened interplay of work, stress, isolation and expectations for parenting, family and monogamy. These days, reports regularly surface with the gloomy news that people are working harder and longer and with less satisfaction, that collective levels of stress have increased, that families are isolated and cut off from networks of kin, and that diagnoses of mental illness are growing steadily. To develop drugs to boost libido, Ryan says, is analogous to ‘giving antibiotics to pigs because of the shit they’re standing in’.

At the same time, suggests the historian Coontz, people are investing more of their personal identity in the pair bond, demanding more of their partners while expecting less of the world. With so much at stake in a relationship, from personal identity to financial security, one might sooner find fault with one’s own mind and body than attribute feelings of numbness to the nature of togetherness itself.

And yet, there is a collective hunger for more and better and different when it comes to desire. It houses our longing for the euphoric and our deepest vulnerability. And as such, it can make us ready targets: sensing we are somehow broken, we want desperately to find a fix.