At universities around the world, students are claiming that reading books can unsettle them to the point of becoming depressed, traumatised or even suicidal. Some contend that Virginia Woolf’s novel Mrs Dalloway (1925), in which a suicide has taken place, could trigger suicidal thoughts among those disposed to self-harm. Others insist that F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925), with its undercurrent of spousal violence, might trigger painful memories of domestic abuse. Even ancient classical texts, students have argued, can be dangerous: at Columbia University in New York, student activists demanded that a warning be attached to Ovid’s Metamorphoses on grounds that its ‘vivid depictions of rape’ might trigger a feeling of insecurity and vulnerability among some undergraduates.

This is probably the first time in history that young readers themselves are demanding protection from the disturbing content of their course texts, yet reading has been seen as a threat to mental health for thousands of years. In accordance with the paternalistic ethos of ancient Greece, Socrates said that most people couldn’t handle written text on their own. He feared that for many – especially the uneducated – reading could trigger confusion and moral disorientation unless the reader was counselled by someone with wisdom. In Plato’s dialogue, the Phaedrus, written in 360 BCE, Socrates warned that reliance on the written word would weaken individuals’ memory, and remove from them the responsibility of remembering. Socrates used the Greek word pharmakon – ‘drug’ – as a metaphor for writing, conveying the paradox that reading could be a cure but most likely a poison. Scaremongers would repeat his warning that the text was analogous to a toxic substance for centuries to come.

Many Greek and Roman thinkers shared Socrates’ concerns. Trigger warnings were issued in the third century BCE by the Greek dramatist Menander, who exclaimed that the very act of reading would have a damaging effect on women. Menander believed that women suffered from strong emotions and weak minds. Therefore he insisted that ‘teaching a woman to read and write’ was as bad as ‘feeding a vile snake on more poison’.

In 65 CE, the Roman stoic philosopher Seneca advised that the ‘reading of many books is a distraction’ that leaves the reader ‘disoriented and weak’. For Seneca the problem was not the content of a specific text but the unpredictable psychological effects of unrestrained reading. ‘Be careful,’ he warned, ‘lest this reading of many authors and books of every sort may tend to make you discursive and unsteady.’

By the Middle Ages, the potentially harmful effects of text had become a recurrent theme in Christian demonology. According to the late University of Washington free speech expert Haig Bosmajian, author of Burning Books (2006), texts that probed Church doctrine were denounced as poisonous substances with destructive consequences for the body and soul. Unsupervised reading could be heresy, the Church feared, and blasphemous texts, such as the Jewish Talmud, were consigned to the fires or ‘metaphorised into deadly serpents, pestilence, and rot.’

The representation of reading as a medium through which readers become psychologically disoriented and morally contaminated continued to influence Western literary culture through every historical epoch. In 1533, Thomas More, the former Lord High Chancellor of England and fierce opponent of the Protestant Reformation, denounced the publication of texts written by Protestant theologians such as William Tyndale (1494-1536) as ‘deadly poisons’ that threatened to infect readers with ‘contagious pestilence’. Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, terms such as ‘moral poison’ or ‘literary poison’ were frequently employed to draw attention to the capacity of a written text to contaminate the body.

With the emergence of the novel in the early modern era, the risks posed by reading to the state of mind of the reader became a regular source of apprehension. Critics of the novel claimed that its readers risked losing touch with reality and consequently became vulnerable to serious mental illness.

The English essayist Samuel Johnson asserted that the realism of fiction, in particular its tendency to deal with the issues of everyday life, had insidious consequences. Writing in 1750, he warned that the ‘accurate observation of the living world’ is more dangerous than the previous ‘heroic romances’. Why? Because since it directly engages with the experience of readers it has the power to influence them. What perturbed Johnson was that the realistic literature directed at impressionable youth failed to provide them with moral guidance. He criticised romantic fiction for mingling ‘good and bad’ qualities of characters without indicating to readers which ones to follow.

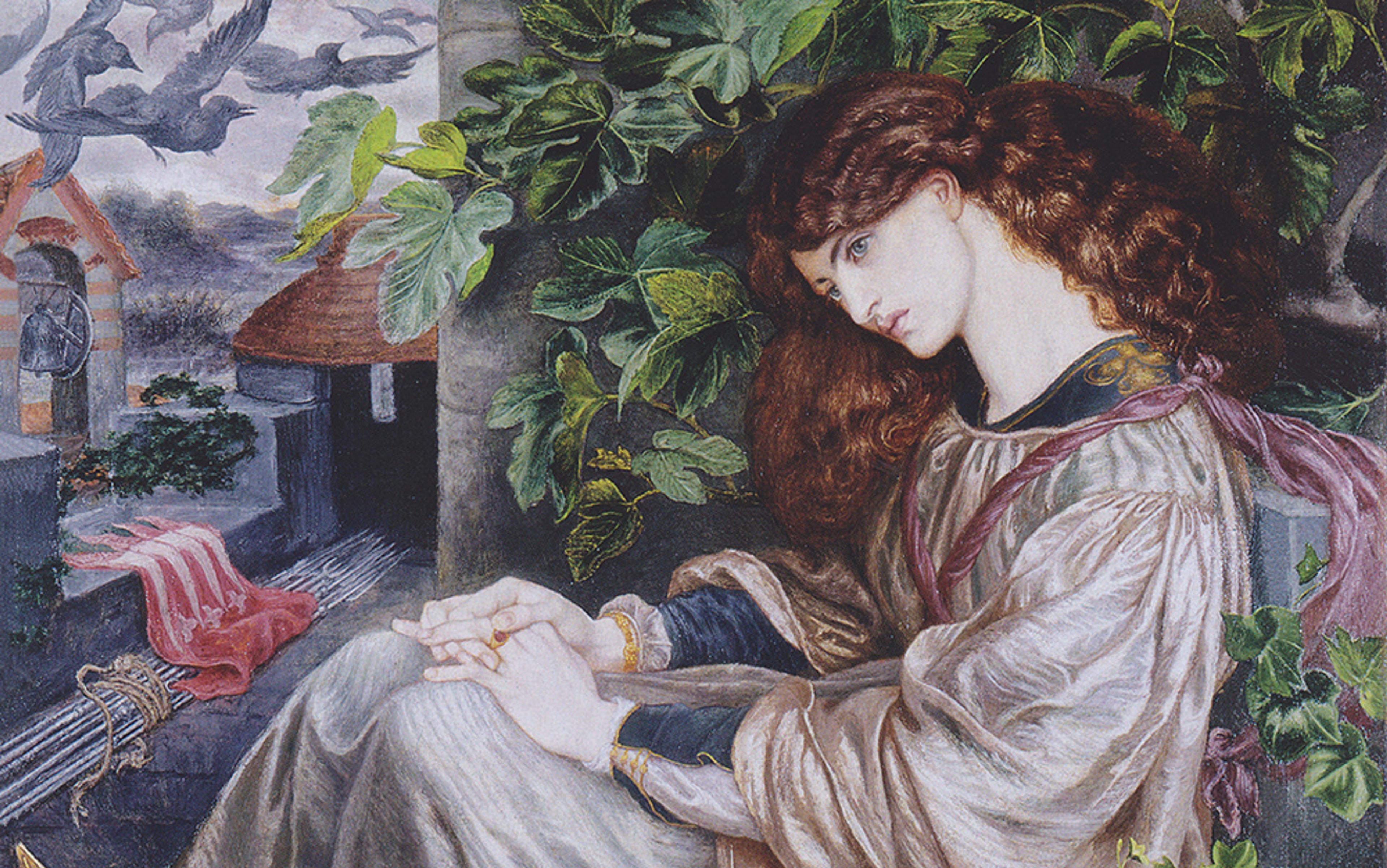

The triggering of dysfunctional imitative behaviour constituted a particular risk to the virtue of women. The philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, writing in his novel Julie (1761), warned that the moment a woman opens a novel – any novel – and ‘dares to read but one page’, she ‘is a fallen girl’.

Continuing in this vein, The Lady’s Magazine of 1780 warned that novels were ‘the powerful engines with which the seducer attacks the female heart’. The novels in question were, of course, popular bestsellers such as Samuel Richardson’s Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded (1740), about a 15‑year-old who resists seduction and rape, and is rewarded with marriage in the end. Those issuing such warnings had no doubt that since women readers were particularly susceptible to powerful emotional arousal, they risked being overwhelmed by unrestrained sexual passions.

Novels were the focus of a moral panic in 18th century England, criticised for triggering both individual and collective forms of trauma and mental dysfunction. In the late 18th century the terms ‘reading epidemic’ and ‘reading mania’ served to both describe and condemn the spread of a perilous culture of unrestrained reading.

The representation of mass reading as an ‘insidious contagion’ was often coupled with sightings of irrational destructive behaviour. The most alarming manifestation of the reading epidemic was its potential for triggering acts of self-harm, including suicide among the impressionable young. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s novel The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) – a story of unrequited love leading to the act of self-destruction – was widely condemned for triggering a wave of copy-cat suicides on both sides of the Atlantic.

Benjamin Rush reported that booksellers were prone to mental illness because their profession required the ‘frequent and rapid transition of the mind from one subject to another’

Though the claims had little basis in reality, they found support in the work of theologian Charles Moore, who published a massive two-volume study, A Full Inquiry into the Subject of Suicide (1790). In this critique and analysis, Moore alleged that Werther was responsible for triggering a wave of suicides among many of its young readers. Despite the lack of empirical evidence, Moore’s study helped to establish a tradition that would associate the reading of romantic fiction with acts of self-harm. His integration of Werther into ‘the scientific’ literature on suicide served as a legacy on which others would draw.

The massive, six-volume study A System of Complete Medical Police, published by the German physician Johann Peter Frank from 1779 through 1819, outlined a comprehensive review of the problem of suicide. Among the numerous causes of suicides, Frank listed ‘irreligiousness, debauchery, and idleness, lavishness and its attendant unaccustomed misery, but especially the reading of poisonous novels’ such as Werther that presented suicide as a ‘heroic display of contempt for earthly affairs’.

By the late 18th and early 19th century, science was invoked to legitimise health warnings about reading. In his Medical Inquiries and Observations Upon the Diseases of the Mind (1812) – the first American text on psychiatry – Benjamin Rush, a founding father of the United States, noted that booksellers were peculiarly susceptible to mental derangement. Recasting Seneca’s ancient warnings in the language of psychology, Rush reported that booksellers were prone to mental illness because their profession required the ‘frequent and rapid transition of the mind from one subject to another’.

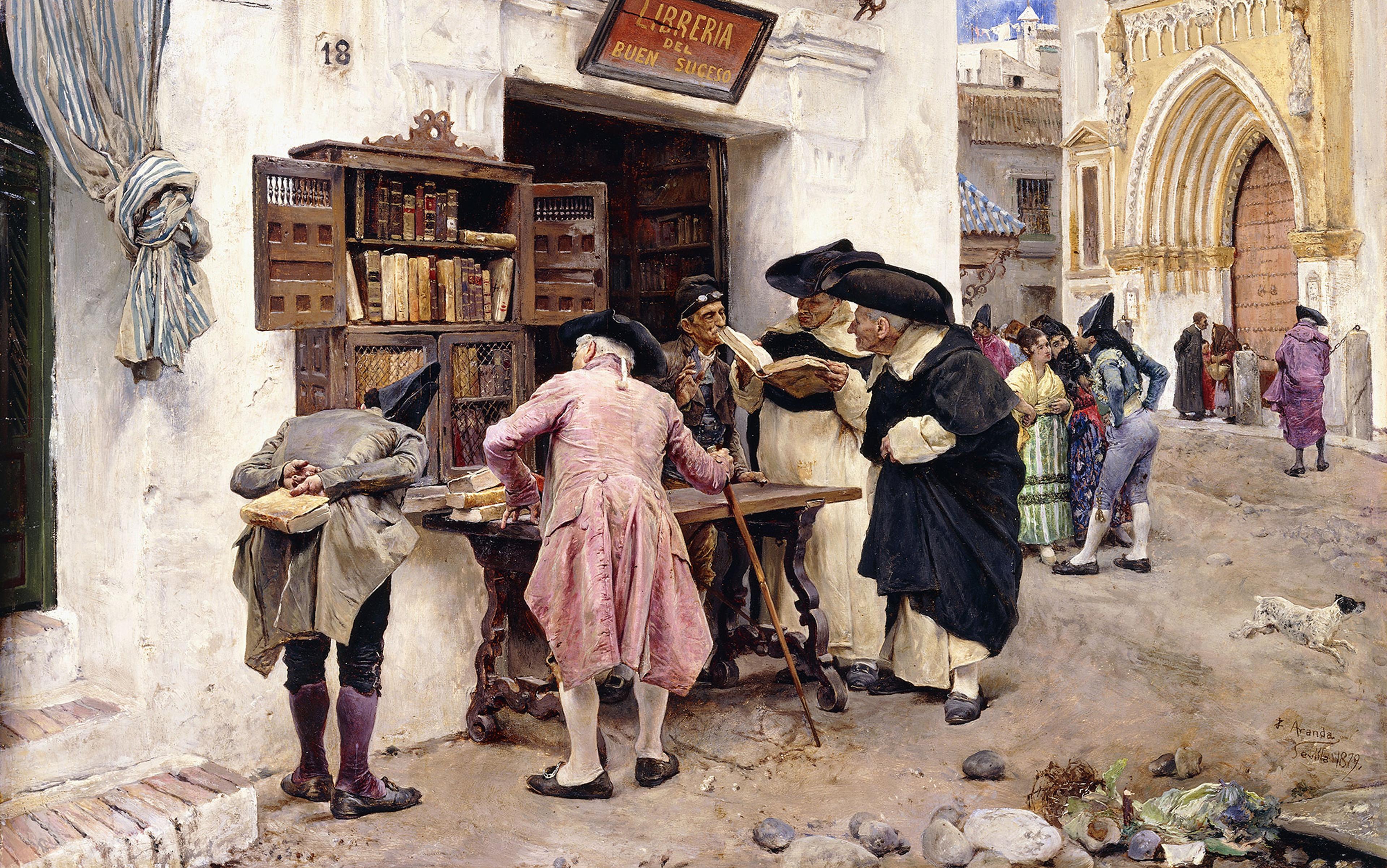

One of the consequences of the emergence of a mass public of readers in the 19th century was the proliferation of warnings about the dangerous medical and moral consequences of popular literature. In 1851, the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer described ‘bad books’ as ‘intellectual poison’, for they ‘destroy the mind’: Karl Spindler’s Der Bastard (1826), Edward Lytton Bulwer’s Godolphin (1833), Eugène Sue’s Les Mystères de Paris (1843) all seemed to pose a risk. It was the very popularity of these novels that disturbed Schopenhauer. He associated popularity with the lowering of cultural tastes, which in turn had toxic consequences on the mind.

During the 19th century, conservative critics of popular literature frequently asserted that readers were directly infected by the sentiments that they absorbed through the reading of the novel. The model of contagion was not simply metaphorical: the absorption of pollutants was portrayed as not only a mental but as also a physical act. From this perspective, sentiment could be caught like a common cold and in many cases it could lead to a traumatic moral disease or even a condition that terminated with the physical act of self-destruction. Although written in 1774, Werther continued to be blamed for inciting its young impressionable readers to commit suicide well into the late 19th century.

During the second half of the Victorian era, the medicalisation and moralisation of reading acquired a new momentum in response to the dramatic expansion of so‑called sensation novels, starting with the spectacular and devastating Madame Bovary (1856). Gustave Flaubert’s great novel features a doctor’s wife who has adulterous affairs in pursuit of passion and intensity, ultimately taking her own life. Following this masterwork was the massive production of cheap, popular ‘penny dreadful’ novels, said to inflict an illness no less serious than that of a physical disease.

Moralisers who feared the malevolent influence of texts drew the conclusion that censorship served the functional equivalent of quarantine

In 1875, the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice issued a report written by the American moralist Anthony Comstock condemning the ‘shrewd and wily’ dealers of obscene material who had ‘succeeded in injecting a virus more destructive to innocence and purity of youth, if not counteracted, than can be most deadly disease in the body …Guard with ceaseless vigilance your libraries, your closets, your children’s and wards’ correspondence and companionships, lest the contagion reach and blight the sweetness and purity of your homes,’ Comstock exhorted teachers and guardians.

Comstock’s call to parents to read their children’s letters and police their reading materials was not simply an expression of Victorian obsession with moral pollution. Like the contemporary advocacy of trigger warnings, Comstock’s demand had as its premise the conviction that dubious texts represented a serious threat to the mental health of the reader.

Moralisers who feared the malevolent influence of texts drew the conclusion that censorship served the functional equivalent of quarantine. For example in 1929, James Douglas, the editor of the Sunday Express, described authors who promoted moral ‘degeneracy’ as lepers. His aim was to force society to undertake the ‘task of cleansing itself from the leprosy of these lepers’.

Despite being bombarded by the language of fear, the reading public cheerfully ignored the health warnings issued by their betters. Throughout most of the modern era, people bypassed the censor and demonstrated a willingness to embark on the journey into the unknown through their reading. Their open-minded approach towards reading was encouraged by humanist and radical cultural currents that affirmed the capacity of readers to benefit from engaging a whole range of texts.

The rise of mass‑market, inexpensive serial literature and sensation novels showed that Victorian moralisers could not inhibit the public demand for entertaining fiction, whatever health warnings they might issue. Meanwhile, in the 21st century, it is the reading public itself that seeks protection from the distressing health effects of reading. And therein lies the difference.

Today, it is not puritanical religious moralists but undergraduate students who demand that Ovid’s poem should come with a trigger warning. For the first time in their career, my academic colleagues report that some of their students are asking for the right to opt out of reading texts that they find personally offensive or traumatising. This self-diagnosis of vulnerability is unlike the traditional call for a moral quarantine from above. Once upon a time, paternalistic censors infantilised the reading public by insisting that reading literature constitutes a serious risk to its health. Now young readers infantilise themselves by insisting that they and their peers should be shielded from the harm caused by distressing texts.

The campaign for trigger warnings represents its cause as an attempt to protect the vulnerable and the powerless from any potentially traumatic and harmful effects of reading. Those who are opposed or indifferent to the call for these warnings are condemned as accomplices in the marginalising of the powerless. Paradoxically, censorship, which once served as an instrument of domination by those in power is now recast as a weapon that can be wielded to protect the powerless from psychological harm.

Often, supporters of trigger warnings draw attention to themselves and their own state of minds and feelings. Their arguments are much more a statement about themselves than an assessment of the content of a text. Indeed, advocates of such warnings are entirely indifferent to the literary merits or the content of the text that they wish to issue with a health warning. What agitates their concern is the conviction that, if readers are unprepared for the unexpected and uncertain experiences encountered through their reading, they might get distressed to the point of psychological damage.

Yet any reports of psychological damage from reading disturbing texts appears to be based on anecdotal rather than rigorous empirical evidence. As the psychologist Richard McNally at Harvard University reported in his review of recent research for Pacific Standard last year: ‘The use of trigger warnings doesn’t just underestimate the resilience of most trauma survivors, it may send the wrong message to those who have developed PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder].’

The key problem raised in the debate on trigger warnings is not psychological but cultural. It highlights the sensibility of vulnerability and minimises the capacity for resilience. That is why university students who have frequently been at the forefront of reading and debating ‘dangerous’ literature can now perceive themselves as unable to cope with unsettling material.

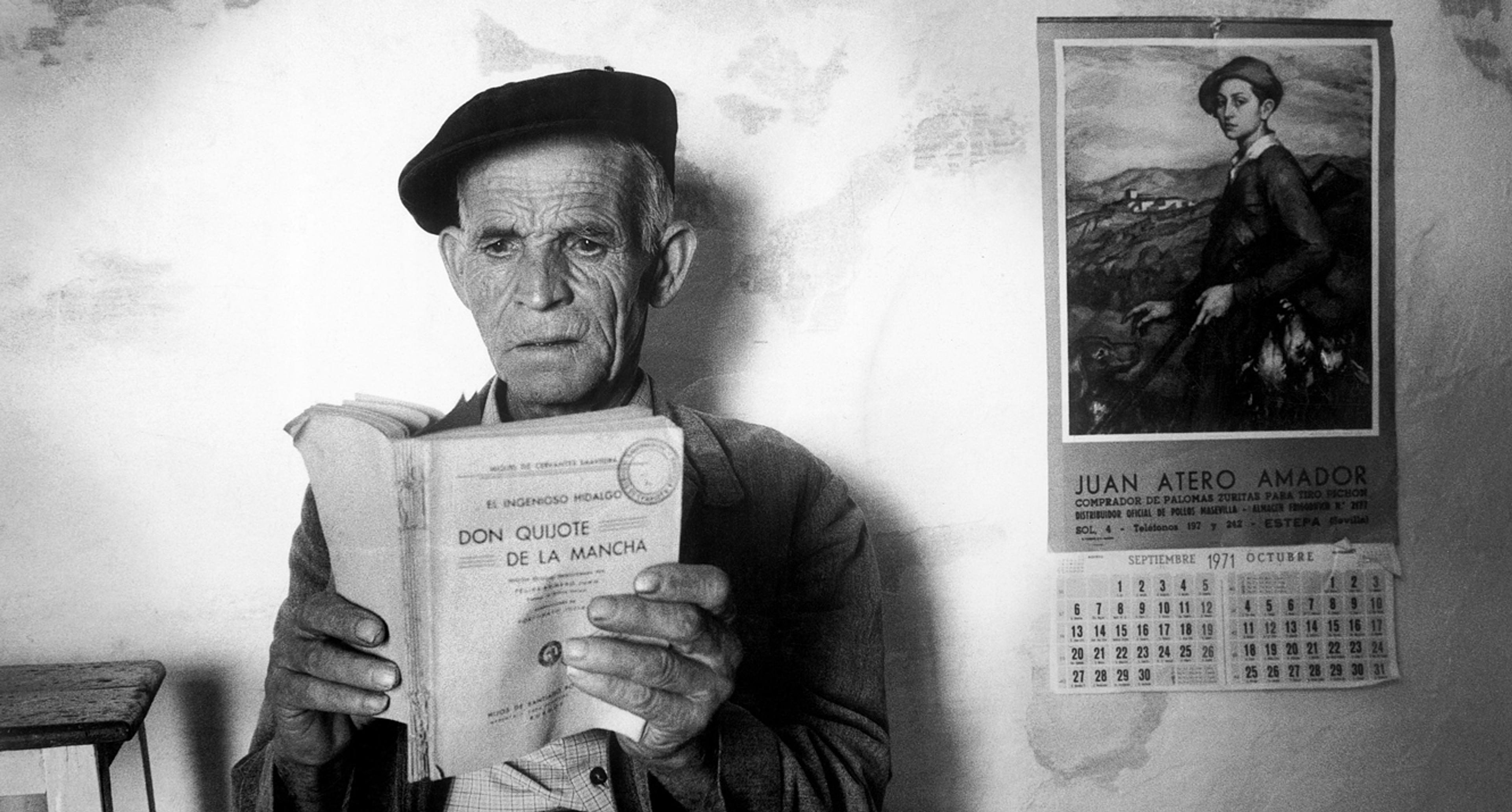

There is one point on which the crusade for the imposition of trigger warnings is absolutely right. It is not for nothing that reading was always feared throughout history. It is indeed a risky activity: reading possesses the power to capture the imagination, create emotional upheaval and force people towards an existential crisis. Indeed, for many it is the excitement of embarking on a journey into the unknown that leads them to pick up a book in the first place.

Can one read Proust’s In Search of Lost Time or Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina ‘without experiencing a new infirmity or occasion in the very core of one’s sexual feelings?’ asked the literary critic George Steiner in Language and Silence: Essays 1958-1966. It is precisely because reading catches us unaware and offers an experience that is rarely under our full control that it has played, and continues to play, such an important role in humanity’s search for meaning. That is also why it is so often feared.