Some time late this century, someone will push a button, unleashing a life force on the cosmos. Within 1,000 years, every star you can see at night will host intelligent life. In less than a million years, that life will saturate the entire Milky Way; in 20 million years – the local group of galaxies. In the fullness of cosmic time, thousands of superclusters of galaxies will be saturated in a forever-expanding sphere of influence, centred on Earth.

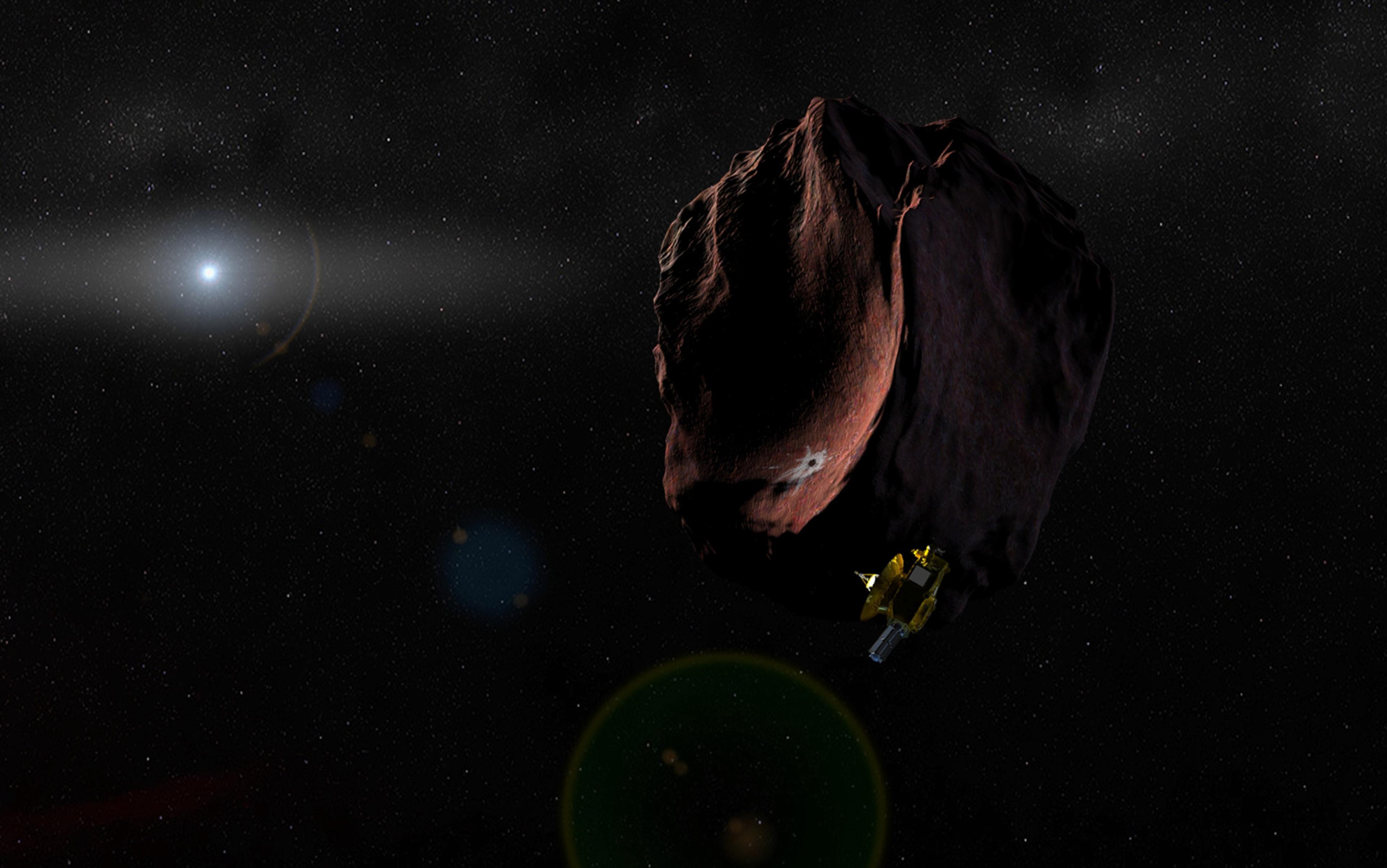

This won’t require exotic physics. The basic ingredients have been understood since the 1960s. What’s needed is an automated spacecraft that can locate worlds on which to land, build infrastructure, and eventually make copies of itself. The copies are then sent forth to do likewise – in other words, they are von Neumann probes (VNPs). We’ll stipulate a very fast one, travelling at a respectable fraction of the speed of light, with an extremely long range (able to coast between galaxies) and carrying an enormous trove of information. Ambitious, yes, but there’s nothing deal-breaking there.

Granted, I’m glossing over major problems and breakthroughs that will have to occur. But the engineering problems should be solvable. Super-sophisticated flying machines that locate resources to reproduce are not an abstract notion. I know the basic concept is practical, because fragments of such machines – each one a miracle of nanotechnology – have to be scraped from the windshield of my car, periodically. Meanwhile, the tech to boost tiny spacecraft to a good fraction of the speed of light is in active development right now, with Breakthrough Starshot and NASA’s Project Starlight.

The hazards of high-speed intergalactic flight (gas, dust and cosmic rays) are actually far less intense than the hazards of interstellar flight (also gas, dust and cosmic rays), but an intergalactic spacecraft is exposed to them for a lot more time – millions of years in a dormant ‘coasting’ stage of flight. It may be that more shielding will be required, and perhaps some periodic data scrubbing of the information payload. But there’s nothing too exotic about that.

The biggest breakthroughs will come with the development of self-replicating machines, and artificial life. But those aren’t exactly new ideas either, and we’re surrounded by an endless supply of proof of concept. These VNPs needn’t be massive, expensive things, or perfectly reliable machines. Small, cheap and fallible is OK. Perhaps a small fraction of them will be lucky enough to survive an intergalactic journey and happen upon the right kind of world to land and reproduce. That’s enough to enable exponential reproduction, which will, in time, take control of worlds, numerous as the sand. Once the process really gets going, the geometry becomes simple – the net effect is an expanding sphere that overtakes and saturates millions of galaxies, over the course of cosmic time.

Since the geometry is simplest at the largest scale (owing to a Universe that is basically the same in every direction), the easiest part of the story is the extremely long-term behaviour. If you launch today, the rate at which galaxies are consumed by life steadily increases (as the sphere of influence continues to grow) until about 19 billion years from now, when the Universe is a little over twice its current age. After that, galaxies are overtaken more and more slowly. And at some point in the very distant future, the process ends. No matter how fast or how long it continues to expand, our sphere will never overtake another galaxy. If the probes can move truly fast – close to the speed of light – that last galaxy is about 16 billion light-years away, as of today (it will be much further away, by the time we reach it). Our telescopes can see galaxies further still, but they’re not for us. A ‘causal horizon’ sets the limit of our ambition. In the end, the Universe itself will push galaxies apart faster than any VNP can move, and the ravenous spread of life will stop.

Communication becomes increasingly difficult. Assuming you invent a practical way to send and receive intergalactic signals, you’ll be able to communicate with the nearby galaxies pretty much forever (though, with an enormous time lag). But the really distant galaxies are another matter. If we assume fast probes, then seven out of eight galaxies we eventually reach will be unable to send a single message back to the Milky Way, due to another horizon. The late Universe becomes increasingly isolated, with communication only within small groups of galaxies that are close enough to remain gravitationally bound to each other.

Our VNP project might encounter another kind of limitation, too. What if another intelligent civilisation had the very same idea, initiating their own expansion from their own home in a distant galaxy? Our expanding spheres would collide, putting a stop to further expansion for each of us. We don’t know if that will happen, because no one has observed a telltale cluster of engineered galaxies in the distance, but we should be open to the possibility. If we can do it, another civilisation can too – it’s just a question of how often that occurs, in the Universe. Taken as a whole, this entire process bears an uncanny resemblance to a cosmological phase transition, with ‘nucleation events’ and ‘bubble growth’ that come to fill most of the Universe. There is even ‘latent heat’ given off in the process, depending on how quickly these massive civilisations consume energy.

Despite the limitations imposed by nature, suffice it to say that a single VNP launch would offer an unimaginable wealth of the Universe’s resources to dispose of as you wish. OK, maybe not you, but whoever programs that VNP. Which raises a rather sticky point – what exactly should they do? It’s easy to imagine VNPs pillaging the resources of the Universe for no good reason, but what’s the actual benefit? What would motivate anyone to do anything like this?

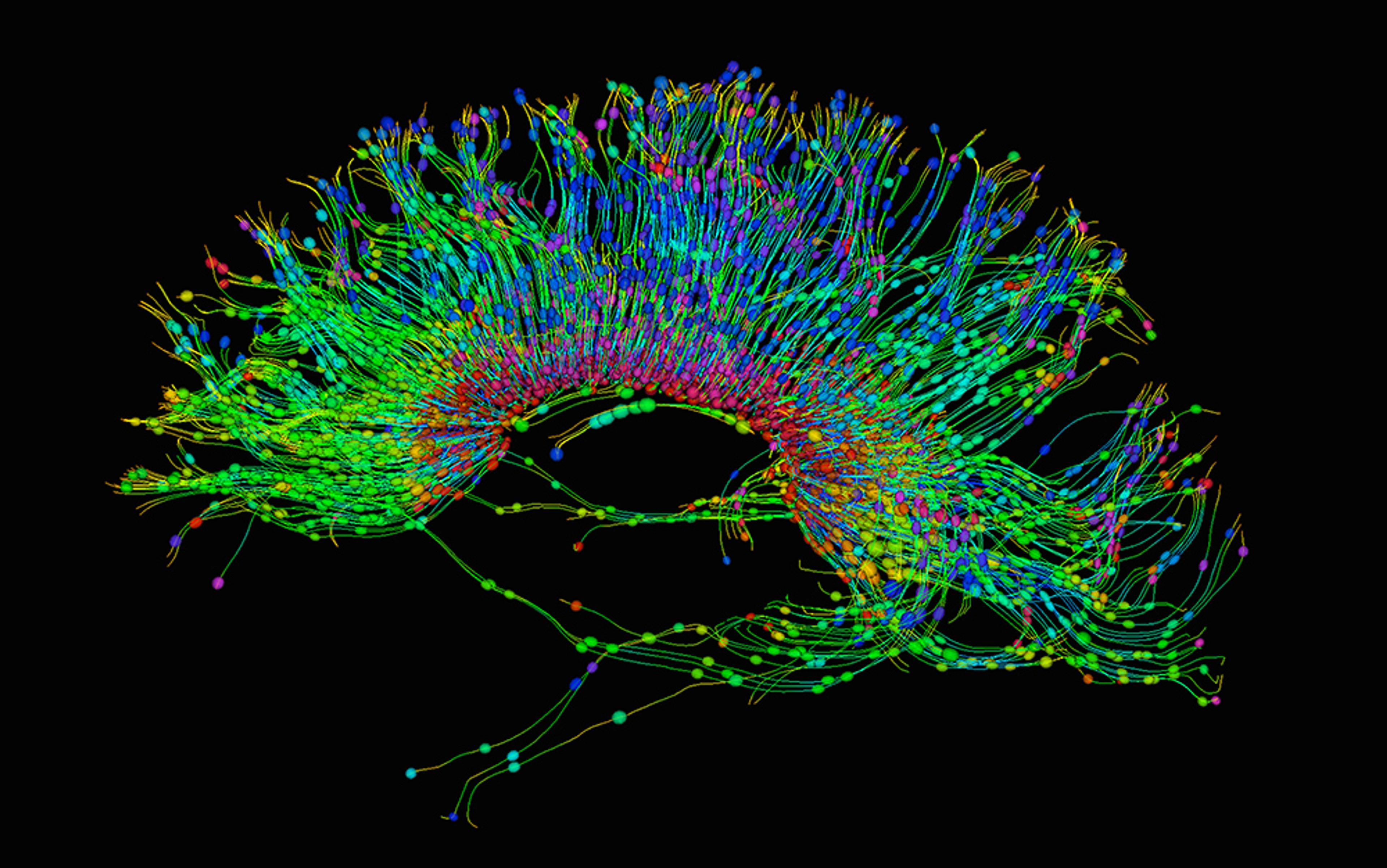

The power it would manifest – millions of years in the future, of course – is so beyond the scale of human experience that we’re still in the earliest stages of imagining what to do with it. It hasn’t even begun to be digested by popular culture and entertainment. But, as a first hint, imagine that, 50 years from now, you were approached to fund a cosmic-scale VNP project. In addition to instructions to ‘reproduce and expand’, each probe will carry a vast library of genetic data and information to reconstruct human bodies and minds on each world, along with an array of plants, animals and cultural information. If you’re still reluctant to fund the project, suppose I throw in a perk: a copy of you, reconstructed with your current memories intact, installed as absolute ruler on countless worlds. Promise of an eternal reign in a heavenly realm has, after all, been known to motivate real people.

But no matter how great your god complex, all the returns-on-investment occur ‘out there’ in space and time, and won’t make anyone rich in the here and now, in the direct manner of, say, asteroid mining. After 1,000 human lifespans, cosmic expansion will still be in its infancy. Don’t expect so much as a snapshot from the nearest large galaxy for at least 5 million years. This pulls us back to the central question. If every direct, tangible benefit is deferred to a weird kind of technological afterlife, why would anyone do it?

The real product of the early space programme was a taste of a new kind of purpose and meaning

At least one answer has been considered by people who think about artificial superintelligence. Maybe we won’t do it – maybe a super-AI will do it for some arcane instrumental reason that doesn’t pay off for billions of years (aggressive resource-acquisition benefits almost any sufficiently long-term goal). I don’t find this answer too satisfying. It’s basically saying that humans will launch VNPs indirectly, by failing to put any limits on an AI’s behaviour. Yes, it could happen, but it doesn’t seem too likely. No doubt the superintelligence control problem is a serious challenge. But writing instructions that constrain an AI to a small region of spacetime should not be the slippery sort of problem that is infinitely easy to get wrong (unlike instructions to ‘make everyone happy’).

Generally, I sense that invoking super-AI makes little difference to the question. ‘Why would anyone do it?’ just becomes ‘Why would anyone use super-AI to do it’? A real answer has to lie with human incentives in the present, on Earth.

So, if there is no direct product in the present, what about the indirect products, that do occur in the here and now? This is where the answer must lie. Space programmes have known about these since Apollo. The early space programme did generate some tech spin-offs, but the real product was something different – it was a taste of a new kind of purpose and meaning, as we constructed the story of humanity’s first tenuous steps into a new realm. In the kind of VNP project we’re imagining here, human meaning will be embedded in a cosmic story spanning billions of years, superclusters of galaxies, and a narrative that grants special status to those who participate. The story will contain a moral dimension too, since you’ll need an overpowering moral imperative to justify appropriating galaxies. Regardless of whether a moral imperative exists at present, if a demand for one exists, a supply will emerge to fill it.

Let’s be sceptical of that last sentence. Perhaps we’re offended by this entire discussion, and conclude that humanity must not despoil the cosmos with VNPs. Further, suppose we have total faith in our ability to convince the world that a ‘no cosmic expansion’ philosophy is the best vision. Well, that’s not good enough, because this philosophy must also compete for all future opinions.

For the sake of argument, let’s say that our ‘no cosmic expansion’ philosophy is dominant for 1,000 years before briefly falling out of favour, allowing a single VNP to be released. The net outcome for the cosmos is identical to a world in which our philosophy never existed at all. No, reliance on human persuasion is insufficient, if we’re really committed to the cause. A more practical, long-term way to safeguard the Universe from life would be to launch a competing project of cosmic expansion, using our own VNPs. One whose goal is to spread everywhere and, with minimal use of resources, do nothing but prevent others from gaining a foothold on the trillions of worlds we come to occupy. Only then can we smugly sit back and let it all go to waste in sterility.

The point is that any competing philosophy with a sufficiently strong opinion must adopt some form of cosmic expansion, even if it opposes the entire concept. Those efforts will unavoidably create their own Cosmic Story with Moral Dimension, enshrining the progenitors and offering Purpose and Meaning. There doesn’t seem to be any way around it, short of snuffing out humanity before any of this can happen.

What about this ‘Cosmic Story with Moral Dimension that delivers Purpose and Meaning’? That description may seem familiar. That’s because it’s religion, by another name. It could be a secular religion (that will inevitably take offence at religious comparisons), or it could be one that imports spiritual beliefs from pre-existing religions. Either way, religion it will be. Cosmic Story. Moral Dimension. Transcendent Purpose and Meaning for practitioners. One can go further – based on what we’ve seen before, it’s likely to be a cult.

That may sound like a stretch, so let’s unpack it. If your goal is to conquer and utilise the accessible Universe, you’ll need absolute certainty in your philosophy. At least, you’ll need to approach certainty before launching your VNPs (it’s no good changing your mind after the launch!) So, you’ll need to identify and recruit participants inclined to fully commit to your cause. And you’ll need to relentlessly purge dissenters who occasionally arise inside your organisation – they threaten to mutate the ‘absolutely certain’ goal. You’ll also have a strong incentive to adopt secrecy as a tool to prevent infiltration, spying and sabotage from competing groups, or government interference. So, then, what do you call an insular, highly dogmatic religion that ruthlessly enforces conformity? Exactly.

The underlying philosophy will need supreme self-confidence to justify asserting itself on the cosmos, and it must strenuously avoid meddling from outsiders before the launch date. These projects won’t necessarily start out as cults – they may even work against cultish behaviour – but as the decades pass and objectives become less abstract and goals get nearer, they’ll find strong incentives to move in a cult-like direction, and very little incentive to move back.

Another obvious observation is that competing religions tend not to get along with each other. When they do get along, it’s usually because one or more has given up on certain ambitions, and/or stopped taking their doctrine too seriously. They become more agreeable as they become more about ‘personal faith’, and less outward-focused. That condition will not be present in a race to deploy VNPs to capture the cosmos. The next 100 billion years of the Universe will be at stake, depending crucially on events happening today. The future of millions of galaxies. Someone will surely point out that direct physical conflict in the here-and-now on Earth is preferable to cosmic-scale conflict later on. In other words, there will be an incentive to violence, before launch-day.

The most successful cult – by hook or by crook – is going to inherit the cosmos

I’m hardly unique in predicting conflict over future technology. Science fiction loves to do that. Others, like Hugo de Garis, have predicted an eventual world war over the question of ‘whether humanity should build godlike massively intelligent machines’.

But this is different. I’m talking about the few. Conflict between small, secretive groups of highly technical zealots. People who could tell you the distance to the Andromeda Galaxy but hope you don’t want to know. While the rest of humanity is fretting over issues like AI safety on Earth and shouting about impacts to their personal way of life, these people will be thinking about something else entirely, and watching with a jealous eye for others like themselves. Because the most successful cult – by hook or by crook – is going to inherit the cosmos.

There’s an important point we touched on before. Each religion is in competition with the others of the present, but also with the others of the future. Being the first to launch VNPs isn’t enough to guarantee victory over the competition. The reason is that intergalactic travel takes millions of years. Suppose you launch VNPs with a travel speed that’s 50 per cent of the speed of light, and your competitor launches VNPs with a speed 1 percentage point faster. Your competitor then arrives at the nearest large galaxy with a 100,000-year lead. That’s enough lead to capture the entire thing, depending on the dispersal pattern of the probes. The effect is magnified the further out you go; you’ll quickly be cut out of all future expansion, finding every galaxy fully colonised by your competitor by the time your probes arrive. It’s irrelevant if you were the first to launch by a decade, a century, or a millennium.

Thus, if your moral imperative dictates that you capture the cosmos, you want to launch and want to see no future launches by anyone else. This creates an incentive that is truly perverse. If you want certainty that your probes are successful, you’ll have to act to prevent all future competition. It’s hard to imagine many ‘nice’ ways to do that. Even the most heavy-handed political schemes tend to become uncertain in less than a century. A group that successfully launches first will be placed in an awkward position, weighing the wellbeing of one planet – Earth – against the future of millions of galaxies. In a nightmare scenario, a truly committed cult could become the most extreme kind of death cult, determined to leave a poison pill for the rest of us, to ensure the ‘correct’ cosmic outcome. No one knows the probability to assign to any of this, but it’s unwise to ignore incentives just because they’re horrific. The strength of the incentive is magnified by the scale of the future. If the future promises to be big and glorious enough, almost anything is justified in the present to ensure a righteous outcome. We’ve seen a similar moral calculus at work in 20th-century political movements, and real-world implications of this kind of futurist reasoning are already appearing in the present day, as with the case against Sam Bankman-Fried.

What happens when those incentives reach their maximum possible strength, with the cosmic future in the balance? I’ll advance a picture that seems plausible to me.

The humans recruited would be technical types, and those with connections, money or other useful resources. They would have to be attracted to (or tolerant of) cult-like behaviour, with personalities that accept the demand for extreme control, and for whom personal meaning, ‘secret knowledge’, and a new/special identity are a big draw. They would, of course, also be selected for a proven capacity to keep their mouths shut in the face of any number of red flags.

The overlap of those requirements narrows the pool, yet large numbers are not essential. Just enough to have their fingers in the relevant technologies, and the ability to take them a few steps in their own direction. Imagine something like a secret network within a few powerful companies – one with a charismatic leader (not necessarily a CEO) and a critical mass of followers in key positions, willing to do almost anything to advance the leader’s grandiose cosmic scheme.

I’m favouring small, secretive groups over large, overt players such as governments or big organisations, publicly dedicated to their own vision. The reason is that, for any specific Moral Imperative you might propose, there will be many more people who oppose it than who agree – just as no single, coherent religious sect commands a human majority. Large, overt organisations are also easy to infiltrate and sabotage. Imagine any active politician – even one you think is particularly good. How comfortable would you be in handing over all cosmic resources and the next 100 billion years to a Moral Imperative of their choosing? Can you imagine anyone willing to take extreme measures to prevent it from happening? And what do you think would happen if, let’s say, the UN wanted to select the Imperative by vote?

The sci-fi we all grew up with trained us to think too small about the future, in space and time

I suspect that getting and maintaining sufficient agreement, secrecy and control implies a small group. Small groups could tap ‘off-the-shelf’ technologies as they become increasingly available. High availability implies that more small groups will compete, when the time is right.

What does this imply about the Moral Imperative itself? It will probably incorporate extreme versions of beliefs that are trendy with engineering types at the time (two or three generations hence), with a proven ability to evoke strong emotions and commitment. A lot of history will occur between now and then, so I hesitate to even speculate on the theme it will take. I seriously doubt it will be an idea that is fashionable today.

Where are we are in this timeline right now? In the very early days. References to our interplanetary future are still largely found in science fiction; yet it’s a great irony that the big-budget sci-fi we all grew up with trained us to think too small about the future, in space and time. Fictional world-building invoked fanciful notions like faster-than-light space travel and ‘aliens everywhere’ so that events could unfold in a short time, and not too far away. It was never a case of invoking implausible tech as part of ‘thinking big’. The real Cosmic Story is yet to be imagined.

The most distant and uncertain part of the picture is the Moral Imperative. I haven’t seen one that looks compelling. Eventually, I expect there to be many. For now, though, the heavy lifting is done by the vastness of scale, not by the moral dimension – but eventually, it must become the ultimate driver. Of course, the most dedicated agents may not make their programmes public. Someone with a coherent long-term plan might prefer this state of affairs to persist as long as possible, where no one can imagine a moral imperative connected with ‘outer space’ – simply as a matter of having less competition.

Finally, what about Purpose and Meaning? It’s making an appearance already. However one might critique longtermism in detail, it has surely discovered a powerful human response that won’t be going away. Since Copernicus in the 1500s, humanity’s place in the Universe has been continually and relentlessly demoted by astronomy. Unfortunately, human meaning was demoted along with it. Wouldn’t it be intoxicating, then, to learn that the entire point of that 500-year enterprise wasn’t to show us our insignificance, after all? The real purpose, I submit, was to comprehend the scale of events that we mere mortals would be setting in motion.

This Essay was made possible through the support of a grant to Aeon+Psyche from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. Funders to Aeon+Psyche are not involved in editorial decision-making.