‘Just try to explain to anyone the art of fasting! Anyone who has no feeling for it cannot be made to understand it.’ Franz Kafka: ‘A Hunger Artist’ (1922)

Brenda Conley was 20 years old when she stopped eating. A simple statement, yet it defies comprehension. Why would a seemingly cheerful young woman from rural Ontario – a recent graduate of an agricultural college, about to be married – choose to waste away? If you had asked her then, she would have said she wanted to look good in her bridal gown. A shy, slim redhead, Brenda had never been unduly concerned with her appearance; her greatest pleasure was tending the cows at her parents’ dairy farm, and her usual outfit involved a sweatshirt and a pair of rubber boots. Nonetheless, she began shunning breads and cereals, then animal protein, then most fruits and vegetables.

Soon Brenda (not her real name) was going without nourishment for days on end. At the wedding reception, she choked down a few bites of salad and cake before resuming her fast, which continued after she moved with her new husband to his parents’ farm. Whenever worried family members begged her to eat, she insisted she wasn’t hungry. She thought of food constantly, but each time she took even a nibble, she was overcome with panic and self-loathing. And the longer she denied herself, the calmer, more focused, and more energetic she felt. She threw herself into housecleaning and quilting with an intensity that puzzled and frightened those around her.

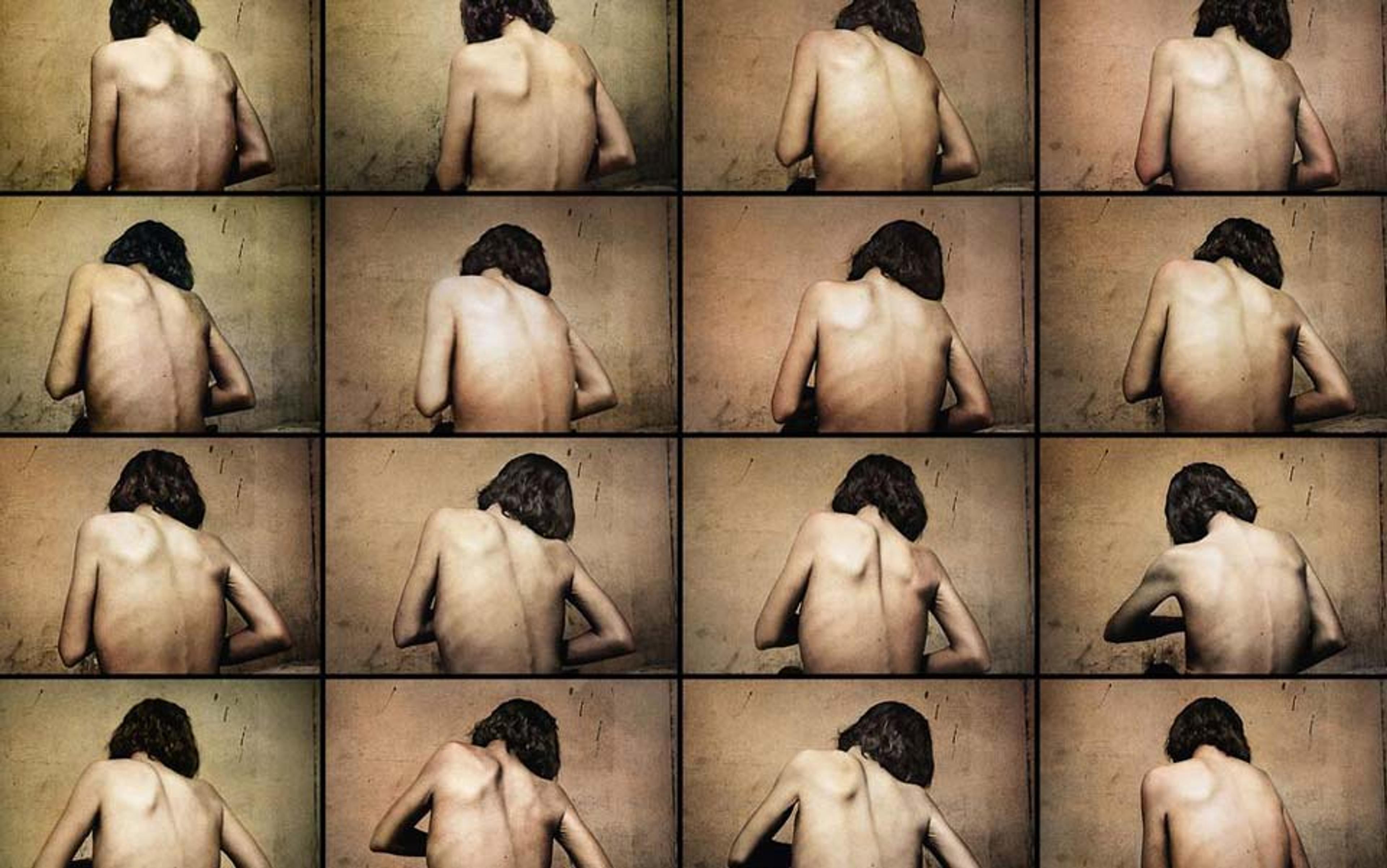

Over the next few months, the flesh melted from Brenda’s 170 cm (5-foot-7-inch) frame; to compensate for the loss of insulation, her skin grew a coat of light fuzz known as lanugo. Her body temperature cooled, her heartbeat slowed, and her menstrual periods ceased. Eventually, her hyperactivity gave way to deep lethargy. Yet even when her weight dropped to a cadaverous 79 lbs (36 kg), the woman she saw in the mirror still looked appallingly plump.

Shortly before her first wedding anniversary, Brenda collapsed in the bathroom. Near death from starvation, she was rushed to the ER and fed through a tube inserted into her stomach. Doctors diagnosed her with anorexia nervosa, a disorder whose mortality rate – up to 15 per cent – is the highest for any mental illness.

The disease has two subtypes: restricting, in which patients such as Brenda drastically limit their food intake; and binge-eating/purging, in which patients periodically overeat and then induce vomiting or diarrhoea to avoid absorbing calories. The latter subtype is distinct from bulimia, whose sufferers maintain normal or above-normal weight. Anorexia affects nearly one in 100 women over the course of a lifetime; in men, the prevalence is one third of that. There is no effective drug, and psychotherapy works only some of the time. Fewer than half of patients recover fully; another third improve partially. In 15 to 20 per cent of cases, the disease becomes chronic and recalcitrant.

Brenda proved to be among the latter group. She spent almost a year in an inpatient treatment centre; by the time she was well enough to leave, her husband had divorced her. Her parents took her in, but her weight quickly slipped below 100 lbs (45 kg) and she was hospitalised again. Over the next 15 years, she cycled in and out of residential eating-disorder programmes, always relapsing within months of her release. Living on her own was out of the question.

Then, in 2011 – during yet another hospital stay – her doctor told her about a small clinical trial just getting under way. Researchers at the Krembil Neuroscience Centre and the University Health Network in Toronto were attempting to treat anorexia by means of surgically implanted electrodes that would deliver pulses of current to a brain region suspected of contributing to the condition. The technique, known as deep-brain stimulation (DBS), had been used for more than a decade to help control movement disorders such as essential tremor and Parkinson’s disease, and showed promise in treating some mood disorders, but it had never been tried on patients like Brenda.

There was no guarantee that DBS would help her. And though the procedure had a low rate of complications, they could be serious: brain haemorrhage, infection, problems with speech or motor control. Like many anorectics, Brenda suffered from severe anxiety; even a slight disruption in her daily routine could provoke a paralysing crisis. Yet she jumped at the chance to risk this intervention. ‘My mom and dad were asking what I wanted for my funeral,’ she recalls. ‘I thought, this is my last resort. Let’s give it a whirl.’

At a time of blitzkrieg advances in brain mapping, when MRI images of lit-up neural pathways are commonplace, the idea behind the Toronto trial might seem obvious. Yet the theory that anorexia could be caused by faulty brain wiring is relatively new, and scientists are just beginning to trace the circuits that might be responsible. Besides the potential personal benefits, Brenda knew, her turn as a guinea pig could help to unveil the secrets of a baffling, and often deadly, disease.

In her classic Fasting Girls: The History of Anorexia Nervosa (1988), Joan Jacobs Brumberg quotes Charles E Rosenberg’s pioneering history of cholera: ‘A disease is no absolute physical entity but a complex intellectual construction, an amalgam of biological state and social definition.’ Although cases of self-starvation have been recorded for centuries (during the Middle Ages, for example, refusing earthly victuals was a hallmark of female sainthood), it wasn’t until 1873 that the behaviour was identified as the central symptom of a psychological ailment. That year, two eminent physicians – one in England, the other in France – described a syndrome in which otherwise healthy patients, usually young women, developed an aversion to food. Sufferers exhibited increased energy even as their bodies withered; they insisted that they felt no hunger and saw nothing amiss with their appearance. The Frenchman, Charles Lasègue, dubbed the disorder l’anorexie hystérique; the Briton, Sir William Withey Gull, called it anorexia nervosa. (The term anorexia simply means ‘lack of appetite’.) Gull’s appellation stuck.

Psychologists argued over whether anorexia stemmed from family dysfunction or sexual repression

From the beginning, experts debated the cause of the illness, and whether treatment should focus mainly on the body or the mind. Gull considered anorexia ‘a perversion of the will’, curable by supervised feeding. Lasègue asserted that family dynamics played a decisive role. Anorexia, he believed, was most common in girls with indulgent but overbearing parents, and was typically set off by emotional distress. Some Victorian doctors treated anorectics with massage, bed rest, doses of mercury, or electrical stimulation of the skin; others forbade reading and social interaction. Most agreed that hovering parents were the principal impediments to recovery. ‘Parentectomy’ became a near-universal prescription. Patients were sent on sea voyages, dispatched to spas, or confined to ‘hysterical homes’ – anything to remove them from the treacherous family table.

By the early 20th century, the discovery of hormones had sent the pendulum swinging toward body-centred treatments. Anorectics were commonly given insulin, oestrogen, or extracts of thyroid or pituitary glands. In later decades, as such remedies proved ineffective or harmful, attention shifted back to the mind. Psychologists argued over whether anorexia stemmed from family dysfunction or sexual repression; in any event, psychoanalysis was said, by some, to be the cure.

In the 1980s, the death of the singer Karen Carpenter – at 32 years of age, after a long struggle with binge/purging anorexia – led to widespread claims that the Western world was in the grip of an anorexia ‘epidemic’. Critics blamed the supposed upsurge on cultural factors, particularly the diet and fashion industries’ interest in keeping women anxious about their bodies.

Meanwhile, researchers determined that the most effective way to treat adolescent anorectics was the opposite of parentectomy. The new technique trained parents how to supervise feeding in a firm but non-critical way; only when the child reached a healthy weight did therapy aimed at changing behaviour and thinking commence. For adults, a similar regimen (with inpatient programmes assuming the parental role) became the go-to approach. These strategies were better than previous models, but left large numbers of patients as symptomatic as before.

The reason for the high failure rate, researchers say today, is that anorexia (like schizophrenia, obsessive compulsive disorder, and other mental illnesses once blamed on inner conflicts or poor parenting) is a congenital disease of the brain, though environment plays a role. It turns out that anorectics, unlike most of us, are hardwired to feel wonderful when they fast. And they lack the capacity to see how awful they look when they’re down to skin and bones.

Over the past two decades, breakthroughs in genomics, neuro-imaging and other fields have helped to create a broad picture of the biological mechanisms involved. Twin studies indicate that up to 85 per cent of an individual’s risk of developing anorexia is genetic. Genome-wide studies reveal a striking association between the DNA of people with anorexia and those with anxiety, depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder; as a corollary, anorectics are more likely than the general population to suffer from these ailments.

Brain chemistry is also disturbed in anorectics. Levels of serotonin (associated with mood and appetite regulation) are abnormally high, though they drop while the patient is fasting. Levels of the hormone leptin, which signals satiety, are elevated as well.

some of our Pleistocene ancestors developed a mutation that boosted their mood, endurance and alertness when food ran short

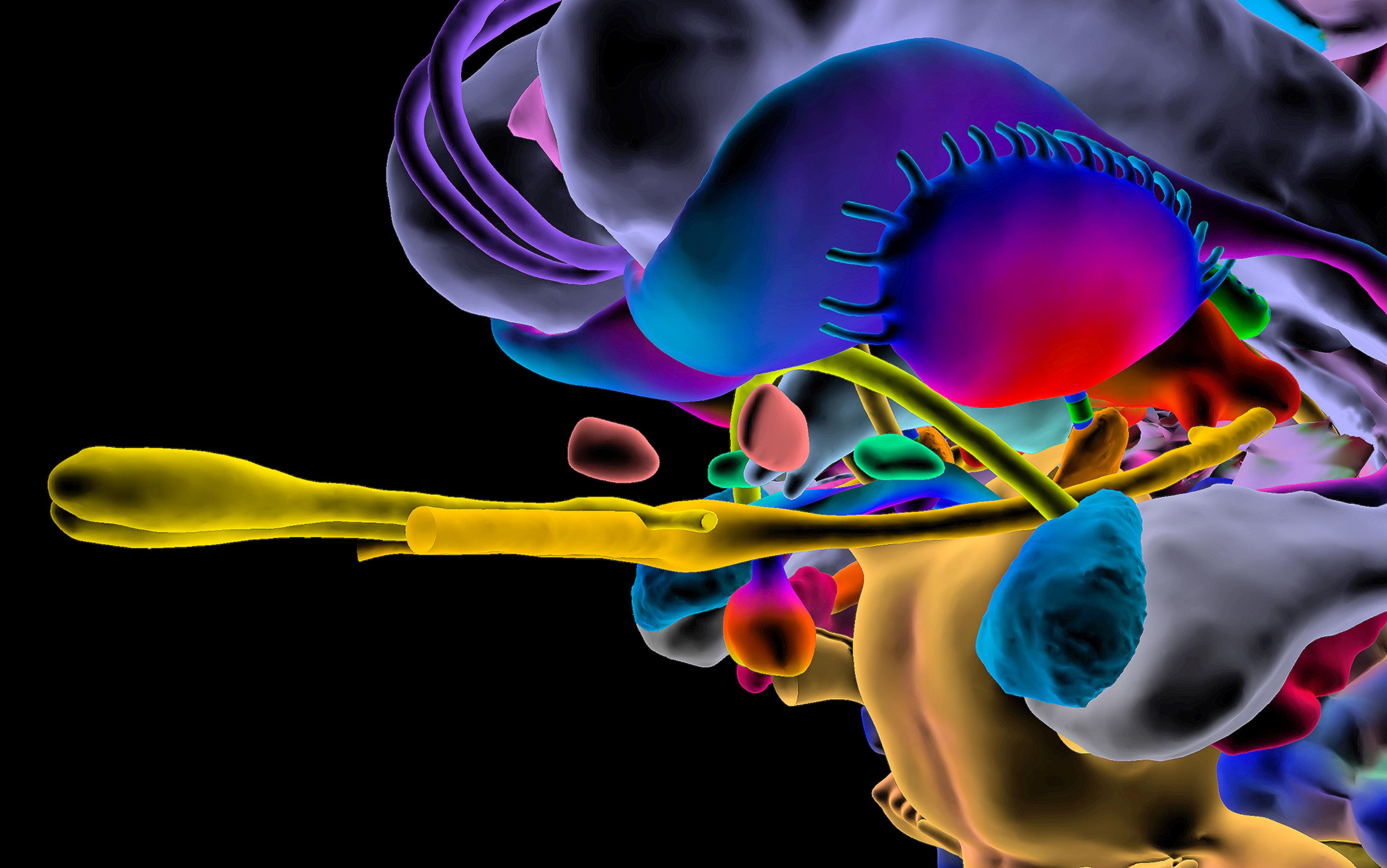

All this translates to glitches in neural circuitry. In brain scans, some areas appear to be overactive while others are underactive. Anomalies are found in the cingulate gyrus, a part of the midbrain involved in predicting and avoiding negative stimuli and also implicated in anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD); the nucleus accumbens, a structure near the brain stem that helps to regulate reward response and is also involved with addiction; and the insula, a region in the forebrain that facilitates communication between brain regions and is also key to feelings of shame and disgust. Regions involved in self-perception behave strangely: when an anorexic woman looks in a mirror, her visual cortex shows markedly less response than that of a normal woman.

A person with an inborn tendency to anorexia might remain asymptomatic until some life event – a painful break-up; an attempt to lose five pounds – makes them reduce their food intake, switching on the relevant genes, according to Cynthia Bulik, professor of eating disorders at the University of North Carolina, who leads the international Anorexia Nervosa Genetics Initiative.

The persistence of the genes despite their dangerousness could be rooted deep in human prehistory. A leading theory, first proposed in 2003, holds that some of our ancestors developed a mutation that boosted their mood, endurance and alertness when food ran short. The author of the ‘adapted to flee famine’ hypothesis, the Montana-based psychologist Shan Guisinger, was trained as a behavioural ecologist, and her anorexic patients’ hyperactivity reminded her of the restlessness that birds display when it’s time to migrate. Their ability to function at a high level while fasting, moreover, resembled that of mother penguins that trek for weeks in search of fish to feed their young. In a world where the difference between deprivation and plenty might lie over the next range of hills, Guisinger speculates, ancient anorectics had the drive to seek out new hunting-and-gathering grounds while their normal counterparts, exhausted by hunger, stayed put.

Whatever evolutionary advantages anorexia might once have conferred no longer apply, of course. Nonetheless, the theory suggests, many modern anorectics may find it impossible to deactivate their famine-survival genes once they’ve been turned on. In some cases, talk-based or behavioural therapies are able to push the ‘off’ button – but more direct methods have long been needed for those who stay sick.

Attempts to treat anorexia by altering the brain date to the 1950s, when surgeons cured some stubborn cases by removing portions of the patients’ frontal lobes. Such radical and irreversible procedures (which can cause troubling cognitive and personality changes) have obvious drawbacks. But DBS might be able to rewire neural circuitry with more precision and far less collateral damage. After the technique was approved for the treatment of Parkinson’s in 2002, scientists began researching its potential for treating mood disorders as well. The method has been tested in clinical trials for depression, OCD and epilepsy, with encouraging results; case studies also suggest it could be useful in treating traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s disease, Tourette’s syndrome, obesity and addiction.

The first clinical trials of DBS for anorexia were completed in 2007, but the results were equivocal. A team in Shanghai used the technique to treat 15 young anorectics whose cases were of relatively short duration. The researchers applied DBS to the reward-related brain structure, the nucleus accumbens; in 12 of the subjects, they also performed a procedure called an anterior capsulotomy (severing connections in the anterior limb of the internal capsule, a structure in the forebrain associated with several psychiatric illnesses, especially OCD). Patients who received both DBS and the capsulotomy showed improvement in eating behaviour, anxiety and OCD, but some suffered side effects including urinary incontinence, confusion and memory loss. Those who received DBS alone were unharmed; they showed improvement in psychiatric symptoms, but little progress in eating behaviour.

In 2009, a team at McGill University in Montreal released a case study of a patient whose eating disorder cleared up when she received DBS for depression. The following year, Nir Lipsman, a neurosurgery resident at the University of Toronto, decided to do his PhD research on DBS as a possible treatment for anorexia. He wanted to see if the disorder could be controlled by targeting the subcallosal cingulate, an area near the front of the midbrain known to play a role in mood regulation. As collaborators, Lipsman enlisted Andres Lozano, the head of his department and a pioneer in DBS treatment for Parkinson’s and mood disorders, and Blake Woodside, a University of Toronto psychiatry professor and the medical director of the eating disorder programme at Toronto General Hospital. The team began recruiting subjects for a phase I clinical trial to gauge the method’s safety.

In the 18 years since she was first diagnosed with anorexia, Brenda has developed her own theory of how she succumbed to the disease. She was always anxious and insecure, she explains, but she hid her fears behind a sunny, compliant manner. Her fiancé was domineering and abusive; she didn’t want to marry him, but she didn’t know how to say no. After the wedding, he forbade her to work in the cow barn – the one place where she felt entirely confident. ‘I was losing myself,’ she says. ‘The only thing I could control was my food, and that’s what I did.’

When she first fell ill, in the late 1990s, Brenda received the standard treatment for anorexia: a course of intensive re-feeding, followed by individual and group psychotherapy. She underwent this process at least a dozen times, at a variety of institutions, but it failed to loosen the disease’s grip. In therapy sessions, she said what she thought her doctors wanted to hear; at mealtimes, she ate just enough to earn a few privileges and boost her weight toward the minimum required for release. Back at her parents’ farm, despite a regimen of anti-anxiety meds, her compulsions again took over. A voice in her head told her what and when she could eat – very little, very seldom – and harangued her about the padding she’d put on. The only thing that calmed her, besides her family’s animals, was the feeling of fasting.

By the time she heard about the experiment in Toronto, she was eager to escape the prison of her illness. ‘At the hospital, I was being stomach-tubed again,’ Brenda recalls. ‘They were talking about putting me in a nursing home.’ The DBS trial seemed a welcome alternative.

The other five women chosen for the pilot study were equally desperate. Like Brenda, they were all long-term sufferers of life-threatening, treatment-resistant anorexia. Their ages ranged from 24 to 57, and their mean duration of illness was 18 years. Between them, they’d been hospitalised almost 50 times.

The trial they had signed up for was in many ways a shot in the dark. Although stimulating the subcallosal cingulate had seemingly helped the McGill patient overcome anorexia back in 2009, her case was far less severe than theirs. Her eating disorder, moreover, was tied to her depression; there was no guarantee that DBS would work for patients (such as some in the Toronto group) whose anorexia came coupled with other mental illnesses, for example anxiety or OCD, or with none at all. The success at McGill might have been a one-off, or a fluke.

Still, there was reason for hope. Deep-brain stimulation works much like a heart pacemaker: by delivering a regular electrical pulse to misfiring nerve cells, it helps them fall into a steady, co-ordinated rhythm. In the brain, tuning one network can affect many others. So even if the subcallosal cingulate wasn’t the perfect target, improving its function might have benefits elsewhere – for example, by lifting patients’ mood enough to let them benefit from other therapies. In any case, it was a place to start: ‘We had to go in through the side door,’ Lozano, Toronto’s DBS pioneer, said. ‘We don’t know what the front door is.’

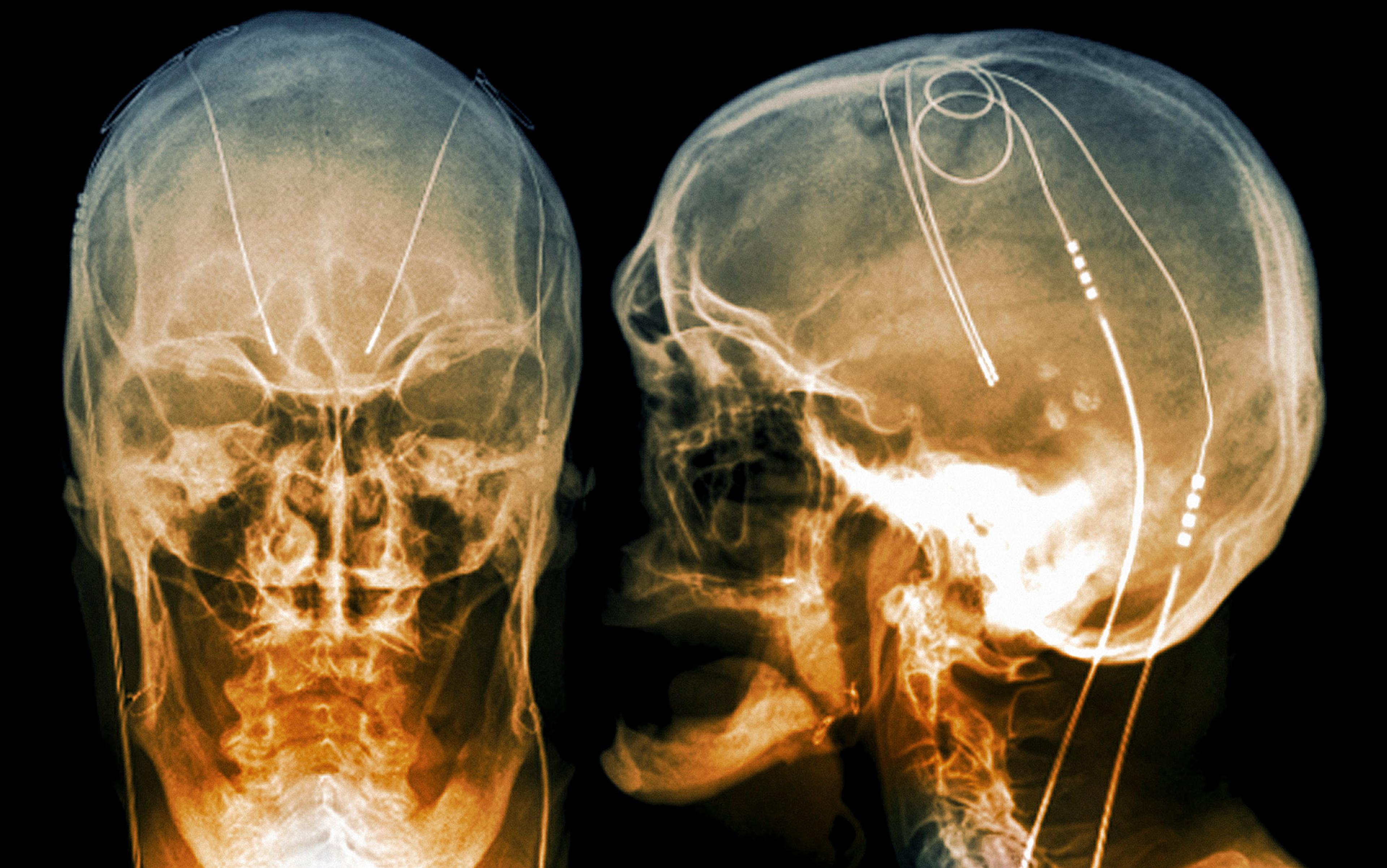

In December 2011, Brenda was given a sedative and strapped on to an operating table at Toronto Western Hospital. Lozano immobilised her head using a metal structure called a stereotactic frame, administered a local anesthetic, and drilled a small hole in her skull. Using co-ordinates from an MRI scan to guide his work, he threaded two wires tipped with electrodes into their target regions on each side of her brain. As he probed, he activated the electrodes and asked Brenda to report on any changes in mood or perception. Once the electrodes were in place, Lozano inserted a small, battery-powered pulse generator under the skin of her chest, and connected it to the wires.

Within a month of the surgery, the device began to malfunction, turning itself off and on at random. Doctors used a remote control to reprogram it, but Brenda had already grown more skeletal. After three weeks in the hospital, she gained enough to go home, but by September 2012 she’d dwindled to 75 lbs (34 kg) – the lowest weight of her adult life. She went back to the ER for tube-feeding, then checked into another inpatient eating-disorder programme.

This time, though, things were different. Her anxiety receded noticeably, enabling her to absorb the lessons that the programme was trying to teach. In therapy sessions, she began to emerge from her shell. ‘I was much more open with everybody about how I was really feeling,’ she recalls. ‘I was very honest with myself.’ She was released in April 2013, at 123 lbs (56 kg), and has not been hospitalised since – her longest stretch away in nearly two decades.

The researchers are pondering other brain regions as potential targets

Around the same time, the Toronto researchers published their initial findings in The Lancet. Three of the patients (including Brenda) had achieved the greatest and most sustained weight gain since the onset of their illness. Four experienced improvements in mood, anxiety, obsessions, compulsions, and control over emotional responses; as a consequence, two subjects were able to complete an inpatient eating-disorders programme for the first time. Only one patient experienced a serious complication – a seizure while the implant was being programmed, which did no lasting damage. And only one (the sole subject who did not suffer from a psychiatric disorder in addition to anorexia) failed to show any change. It’s well worth noting that of the patients who did improve, changes still required extensive therapy programmes of four to six months. This suggests that improvements did not result from a placebo effect; if patients had been fooled into thinking the treatment worked, it would have kicked in immediately, not months out. DBS, it appeared, had at least partially normalised their brain circuits. The cruel syndrome passed down from their Stone Age ancestors was on its way to being tamed.

Since the Lancet paper was published, the study has entered phase II, in which the efficacy of DBS is being tested on a larger group. So far, 15 patients have received an implant; among the eight who have been followed for at least a year, three have achieved and maintained more or less normal weights. The researchers are pondering other brain regions as potential targets. Scientists elsewhere are preparing their own experiments aimed at replicating or expanding on the Toronto team’s work.

Brenda, now 38, lives in a small townhouse, the first home she’s ever been able to call her own. Every morning, she drives with her dog to her parents’ farm, where she cares for five sheep and two horses – animals her family bought her when they realised she was well enough to handle the responsibility. She recently became a leader of her local 4H youth club. ‘I could never have done that before,’ she says. ‘Getting to meetings is anxiety-provoking, but I enjoy them once I’m there.’

She doesn’t know her current weight (her therapist won’t let her look at a scale), but she guesses that it still isn’t optimal: ‘If somebody saw me coming down the street, they’d say, She’s not feeling 100 per cent, I don’t think.’ Brenda is still on medical disability, and doesn’t consider herself cured.

But DBS has given her something she once could get only by starving: a feeling of control. ‘I can manage my anorexia now,’ she says. ‘It’s kind of like a whole new life.’