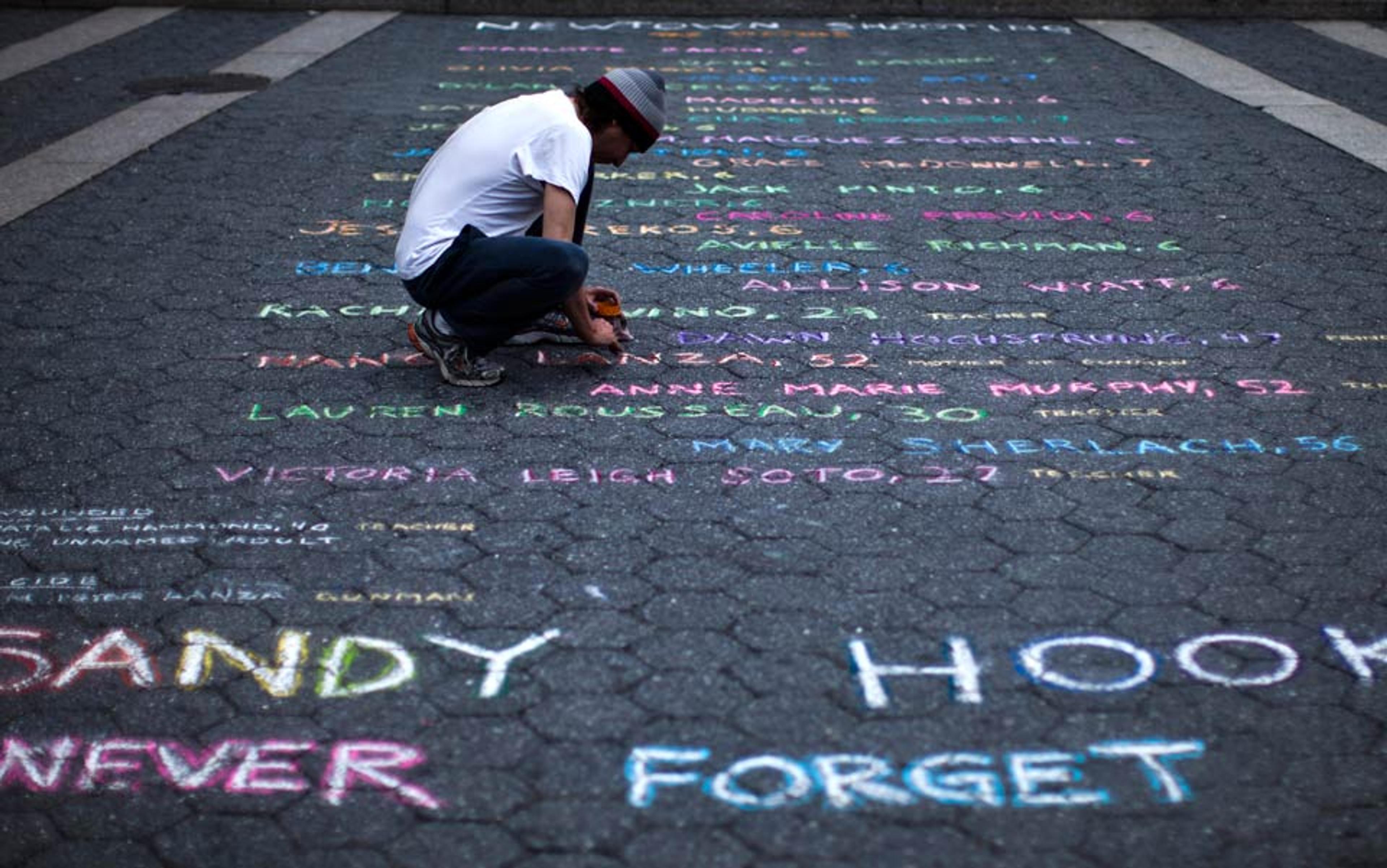

A movie theatre in Aurora, Colorado. Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut. The Washington Navy Yard. The college town of Isla Vista, California. Most of us recognise these as US sites of recent mass murder, loosely defined as the intentional killing of more than four people in a single incident. Unlike the casualties of war or gang-related murders carried out in inner cities, these acts of domestic terrorism strike a particular brand of fear in the hearts of Americans because they seem to be random acts committed in places where such behaviour is unexpected.

Naturally, we respond by trying to pinpoint the cause: bad parenting, mental illness, guns, video games, the media, heavy metal music, or just plain evil. Once some ‘other’ is identified as an offending agent, we set up a kind of quarantine so that it can be banished from society and no longer threaten. Hoping to allay fears and respond to emotionally charged demands for action, politicians jump on this or that bandwagon with proposals for legislation aimed at sequestering and eliminating would-be culprits. Then we go about our lives, until the next mass shooting occurs and the cycle is repeated.

In the short term, this process makes us feel safer than looking inward and thinking: ‘There but for the grace of God go I.’ But what if the reality is that the underlying cause of mass murder lies not in something external to ourselves, but rather something at the root of human instinct and behaviour that’s also interwoven into American popular culture? This possibility suggests that, rather than trying to get rid of some offending external agent, a more meaningful approach might require looking within ourselves and our own communities for a solution.

In support of this idea, James Fox and Monica DeLateur, criminologists at Northeastern University, published a paper last year in Homicide Studies that dispels some myths about mass shootings and calls into question our tendency to blame things outside of ourselves. To begin with, the authors note that ‘mass shootings have not increased in number or death toll, at least not over the past several decades’. They then go on to demythologise a number of common assumptions about mass shootings. Contrary to popular opinion after the Columbine High School massacre in 1999, in which two schoolboys murdered 12 fellow students and a teacher, violent entertainment doesn’t seem to be a significant cause of mass murder. In terms of interventions, neither tighter gun control nor arming our schools are likely to reduce mass shootings. Even expanded efforts at profiling would-be mass murderers or enhancing mental health services might be futile. Needless to say, these conclusions aren’t very encouraging and the authors end by suggesting that we ought to continue ineffective responses in any case because ‘doing something is better than nothing’.

Perhaps we need to look at these elements within the context of the culture itself. Guns are instruments for killing, but as the founding fathers of the US recognised in placing gun rights directly into the Constitution, they can also be effective tools for equalising power and overcoming oppression. Indeed, the US was born out of violent revolt, and the idea of the underdog responding with force to defeat an aggressor has been an archetype for the US hero ever since. As a nation, Americans see themselves as promoters of armed rebellion in the name of freedom and democracy around the globe.

Over the past century, generations of US boys have grown up romanticising the Wild West by playing ‘cowboys and Indians’ with replica six-shooters, battling each other as ‘cops and robbers’ armed with plastic revolvers, or staging vast campaigns of toy soldiers in which opposing armies were gunned down in droves. More recently, ‘first-person shooter’ simulations featuring both military and criminal role-plays have become some of the most successful video games of all time. A casual perusal of the top-grossing films of the past two decades is replete with examples of movies intended for children and adults alike that glorify gun violence along with posters featuring heroes posing with firearms, even in comedies.

And while it’s technically true that ‘guns don’t kill people, people kill people’, the phrase ‘guns don’t kill people, but people kill people with guns’ better portrays the relationship between guns and killing. Guns have popular appeal in our society because they can make us feel powerful and safe, in a world that feels increasingly dangerous and uncertain to many. It would seem that the fear of falling victim to the kind of violence featured heavily on the nightly news, ranging from domestic murder to global terrorism, has become something of an industry in the US. At the same time, whether morally justified or rationalised, protecting oneself and one’s family by arming against ‘the bad guys’ and taking ‘an eye for an eye’ remains an enduring US fantasy.

Of course, while violent fantasies might very well reside somewhere within the average US male, they’re often just that – fantasies. Thankfully, the vast majority of us do not discharge a firearm in self-defence, much less commit murder. So, how do we explain why mass murder, although infrequent, does sometimes occur? A typical response would have us believe the answer lies in mental illness or, if not illness per se, then individuals who are somehow flawed and different from the rest of us – ‘psychopaths’, ‘losers’, or ‘evildoers’. Proposed solutions, usually couched in terms of enhancing mental health services, often involve plans to further marginalise those struggling with emotional issues, screening them based on risk factors and warning signs so that they can be locked away in psychiatric hospitals or prisons, which themselves have become the largest mental institutions in the US. Such proposals reflect the instinct to cull such individuals out of the pack so that they can be banished from society.

These risk factors for mass murder are not necessarily the domain of mental illness, but rather the ‘psychiatry of everyday life’

However, efforts to profile mass shooters don’t support mental illness as a root cause. For instance, a 1999 publication by the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) suggested a wide variety of risk factors for school shooters, including depression, alienation, narcissism, poor coping skills, low frustration tolerance, lack of trust, fascination with violence-filled entertainment, negative role models, low self-esteem, access to weapons, and the tendency to manipulate others. Such wide-ranging warning signs result in a profile that has reasonable sensitivity (mass shooters often do have multiple risk factors), but very poor specificity (the overwhelming majority of people who have those same risk factors do not become mass shooters). This sets up the problem of ‘false positives’ in which widespread screening would lead to the inappropriate identification of large proportions of the population. While some might find that reasonable, they might also feel very different if they or their child was among those identified at risk.

Mass shooters are almost exclusively white and male, but aside from that there is no one profile of the group. In defiance of stereotypes, most mass shooters are not psychotic, delusional, ‘crazy’, or ‘insane’. A 2002 US Secret Service report found that the majority of school shooters have had a history of ‘feeling extremely depressed or desperate’ (not the same as having a clinical diagnosis of major depression) and nearly 80 per cent had considered or attempted suicide in the past. Almost all had experienced a major loss such as a perceived failure, loss of a loved one or romantic relationship, or a major illness prior to the shooting, and about 70 per cent perceived themselves as wronged, bullied or persecuted by others.

Revenge was a motive in the majority of incidents. Christopher Ferguson, a psychologist at Stetson University in Florida whose work has contributed to the debunking of the link between violent video games and violence, recently summarised the most salient features of a typical mass shooter, noting that risk factors for mass murder are similar for both adults and children. These include antisocial traits, depressed mood, recent loss, and a perception that others are to blame for their problems. And herein lies the rub – while this kind of profile implies that mental illness could be an important risk factor, what we’re really talking about are negative emotions, poor coping mechanisms and life stressors that are experienced by the vast majority of us at one time or another. These risk factors are not necessarily the domain of mental illness, but rather the ‘psychiatry of everyday life’.

Therefore, it appears that the most important risk factors aren’t those that set mass murderers apart from the rest of us; instead, they are simply appropriated from culturally sanctioned patterns of aggression. The difference between one who fantasises about revenge and carries it out could be a matter of degree, rather than some bright divide separating a murderer from the rest of society.

Several authors have speculated on how the dynamics between individuals, risk factors and popular culture might set the stage for mass murder. Augusto De Venanzi, a professor of sociology at Purdue University in Indiana, has argued that modern society, with its emphasis on individualism and the pursuit of material happiness, fosters narcissism and that, within the microcosm of white suburban schools in particular, self-worth is defined by the likes of socioeconomic status, achievements in competitive academics and athletics, and fashion. James Knoll IV, a forensic psychiatrist at Upstate Medical University, part of the State University of New York, has written that in such a narcissistic culture or subculture, affronts to self-esteem can be equated with threats to our very survival and that the typical response to such narcissistic injuries is a desire for revenge.

Roy Baumeister, a social psychologist at Florida State University and the author of The Cultural Animal (2005), has concluded that low self-esteem is not a cause of violence and that boosting self-esteem ought to be a reward for, rather than a precondition of, achievement and good behaviour. As a matter of speculation, perhaps the promotion of unconditional self‑esteem of children in more affluent family structures instills a kind of entitlement that helps to explain why mass murder is primarily a crime carried out by white males. When the happiness and social status that one feels is deserved is not forthcoming, feelings of peer rejection, resentment and blame can become all-consuming.

Obsessed with revenge, those aspiring to mass murder draw from the archetypal US hero who relies on gun violence to right wrongs and overturn oppressive institutions. Those who transition from fantasy to action are those who rationalise no other option than murder-suicide by ‘going out in a blaze of glory’. No doubt this rationalisation represents a distinct kind of tunnel vision, distorting the traditional US hero into an anti-hero who regards society as the enemy. But in creating enemies in one’s mind, perception can be reality and moral justifications are subjective. As the saying goes: ‘One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom-fighter.’

In psychiatry, a ‘culture-bound syndrome’ is an idiosyncratic, locale-specific pattern of behaviour that represents a culturally sanctioned expression of distress if not a mental illness per se. In Malaysia, for example, the culture-bound syndrome amok involves episodes of mass violence committed by an individual following a period of brooding. Unfortunately, in addition to borrowing the word amok in our own lay speech, it would appear that the US, along with other Western societies, has developed our own brand of running amok in the form of mass shootings. Once the cultural mythology of such mass murder has been firmly planted into public consciousness, a select few distressed individuals will look to this model to guide their own behaviour, creating the problem of copycat killings.

we should reach out to those who have fallen away from mainstream society, bringing them back to the herd before they come to see only a single, deadly alternative

If mass shootings are difficult to predict, potentially self-perpetuating, and result not from easily eliminated sources but rather from untimely interactions between normal instincts, culturally sanctioned patterns of behaviour and entrenched features of modern society, is there a rational approach to prevention? Inasmuch as marginalisation seems to lie at the heart of the mass murderer’s grievances, further attempts to screen, identify, remove and effectively punish those with the potential to commit such violence are doomed to fail.

Instead, interventions that screen for risk with a goal of reintegrating at-risk individuals into their communities make more sense and bypass the problem of false-positives. This approach doesn’t mean that society is to blame for mass murder, nor does it suggest that we should embrace mass murderers through some kind of ‘Have you hugged a mass shooter today?’ campaign. But it does mean that we should reach out to those who have fallen away from mainstream society, bringing them back to the herd before they come to see only a single, deadly alternative.

Mass shootings are terrifying phenomena that deserve our best efforts at prevention, but it’s high time we resisted the usual knee-jerk defence of trying to find an easy target to blame and eliminate. If you still think that guns are to blame, take care not to remove responsibility from the individuals that wield them. If you think bad parents are the problem, make sure you read Susan Klebold’s heartfelt essay about her son who committed mass murder at Columbine. Support the expansion of mental health services, but know that what we’re really talking about is reaching out to those on the fringe of clearly defined mental illness where there’s no easy solution in a pill.

Let’s also consider re-assessing some of our cultural values and teach our children about different kinds of heroes, how to resolve conflicts, and cope with loss. And, as a recent report from the Making Caring Common Project suggests, let’s prioritise raising children who are kind. The real solution is not about blame, but opportunity. According to the 2002 Secret Service report, mass shootings are not sudden, impulsive acts. They occur with planning that is known to at least one other person in more than 80 per cent of cases. This means that there’s time to reach out – not to a murderer, loser or weirdo; but to someone’s son, student, classmate and neighbour.