Scientists now know much about human mating. The menu includes at a minimum: brief sexual flings, long-term pair-bonding, some infidelity, some polygyny (one man, multiple wives), rare polyandry (one woman, multiple husbands), occasional polyamory, some divorce, and frequent serial mating. These strategies are not well-captured by single labels such as ‘monogamous’ or ‘polygamous’. And we know with reasonable certainty that lifelong monogamy does not describe the primary pattern.

Divorce rates in the United States have hovered just below 50 per cent, and are variable but comparable across cultures around the globe. Among married couples, infidelity is far from a trivial occurrence. In 1952, the sexologist Alfred Kinsey estimated it at 26 per cent for women and 50 per cent for men, although other studies put rates lower or higher. We know that infidelity is the leading cause of divorce worldwide, from the Inuit in Alaska to the !Kung San of Botswana. And we know that most adults in the modern world, including roughly 85 per cent in the US, have experienced at least one romantic break-up.

But there has always been one missing piece of the puzzle when it comes to understanding mating strategies, especially among women. Why do women have so many affairs when these do not increase the number of offspring they can produce?

From an evolutionary perspective, male infidelity is fairly straightforward. Men have evolved a strong desire for sexual variety, stronger than women’s on average, due to the large asymmetries in parental investment. Men can reproduce with as little effort as it takes to inseminate a fertile woman. Women require a metabolically costly nine-month pregnancy to produce a single child. Stated differently, an ancestral married man with two children could have increased his reproductive output by 50 per cent by a single successful reproduction with an affair partner. Adding additional sex partners for women who already have one generally does not, and never could have, dramatically increased their reproductive success.

Yet women do have affairs, a phenomenon that, up until now, has been explained by the ‘good genes hypothesis’: the concept that women have evolved a dual mating strategy – securing investment from one man while mating on the side with men who have better genes than their regular partners.

But the good genes hypothesis fails to explain why, in the wake of infidelity, so many women literally stray, throwing over a current mate for the affair partner. My team’s new concept – the mate-switching hypothesis – fills the gap in scientific understanding, explaining what we observe in the real world. The mate-switching hypothesis posits that women have affairs to extricate themselves from a poor mateship and trade up to a better partner.

For both sexes, the hypothesis explains what we commonly observe: a year after publicly declaring her marriage vows, a woman finds herself sexually attracted to her co-worker. After changing his child’s fifth diaper of the day, a man wonders whether he made a terrible mistake and fantasises about his high-school sweetheart that got away. After six years of marriage, a woman finds that she’s the primary breadwinner and her husband’s laziness has eroded her confidence in their union; she notices that her co-worker lingers longer in the doorway of her office than strictly needed. After years of living a life of quiet desperation, a man starts a passionate affair with his next-door neighbour. A woman confesses to her best friend that she’s in love with another man and surreptitiously lays the groundwork for leaving her husband – a separate bank account and a deposit on an apartment.

These diverse scenarios stem from a common cause – humans have evolved strategic adaptations for mate-switching, a phenomenon that is widespread across species. The simplest such adaptation is the ‘walk-away’ strategy, in which organisms simply physically separate themselves from costly cooperative partners. The mate-switching hypothesis proposes a version of the walk-away strategy underpinned by human psychological adaptations designed to detect and abandon costly mates in favour of more beneficial ones.

Many in modern cultures grow up believing a myth about lifelong love. We are told about falling for the one and only. We learn that the path to fulfilment is paved with a single glorious union. But the plots of fictional love stories often come to a close upon the discovery of that one and only, and rarely examine the aftermath. The story of Cinderella ends with her getting the prince. After overcoming countless obstacles, a union is finally consummated. Few romantic fantasies follow the storyline of committed mating – the gradual inattentiveness to each other’s needs, the steady decline in sexual satisfaction, the exciting lure of infidelity, the wonder about whether the humdrum greyness of married life is really all life has to offer.

In fact, we come from a long and unbroken line of ancestors who went through mating crises – ancestors who monitored mate value, tracked satisfaction with their current unions, cultivated back-ups, appraised alternatives, and switched mates when conditions proved propitious. To understand why, we must turn our gaze to those ancestors and uncover the mating challenges that they confronted.

Ancestral humans faced three great struggles in life. First were the hazards of the physical environment – getting enough food to eat, findings shelter from the storm, fending off extremes of heat and cold. Second were struggles with other species. Survival was always at risk from dangerous snakes, carnivorous cats, and parasites that made human bodies their homes. A third class of challenges proved no less fundamental – competition and conflict with members of our own species. Other humans, with their multifarious slings and arrows, collectively made up a momentous hostile force of nature.

In the context of these struggles, humans evolved a menu of mating strategies, of which long-term committed pair-bonding became central. A committed mate could provide meat during cold winters when no berries were blooming. A long-term partner could offer protection from hungry predators and hostile humans. Life mates could nurture one’s children, the invaluable vehicles that carried precious genetic cargo into the future. Long-term mating, in short, offered a bounty of benefits, aiding in combat against all three classes of human struggles.

But something could always go wrong. An initially promising hunter could get hobbled by injury or infection. A regular partner could get bitten by a poisonous spider, wounded in battle, or killed in inter-group warfare. Or his status within the group could plummet, decreasing his privileged priority for access to the group’s critical resources. A partner’s mate value, initially promising an upward path, could suffer calamitous setbacks. Long-term mate selection is all about future trajectory, and the future often carries with it treachery and tragedy.

The vagaries of life provided new prospects for our ancestors to trade up in the mating market

Another challenge facing a committed mateship is that more valuable mates, initially not present or not available, sometimes appear on the scene. Your mate value might rise, rendering you attractive to potential mates who were initially uninterested. A previously unavailable potential mate could suddenly become unencumbered due to the death or desertion of their own partner. The fusion of two separate tribes could present a fresh wealth of mating opportunities. In short, the vagaries of life provided new prospects for our ancestors to trade up in the mating market.

And on the flip side, individuals could find themselves on the losing end of a partner who becomes disenchanted. A husband might start an affair, diverting valuable family resources to another woman and her children. A man might feel that his status entitles him to a second wife, halving the initial wife’s share of his resources. Or he might divorce her entirely, abandoning her and her two dependent children just as advancing age drags down her mate value and dims her own prospects for re-mating.

All of these ancestral challenges favoured the evolution of strategic solutions. Some solutions involve tactics of mate retention, motivations to fend off mate poachers, and hold on to an investing partner. These tactics range from vigilance to violence. But there existed another important suite of solutions – adaptations for mate-switching, to which we now turn.

Although much scientific research has focused on the initial stages of mate selection and mate attraction, and some on mate retention, relatively little attention has been given to adaptations for mate switching. One of the most important involves monitoring a partner’s mate value, which is made up of dozens of qualities. These include social qualities – the status or esteem in which they are held; their network of friendship and coalitional allies; the power of their kinship alliances. Physical qualities also contribute to mate value, such as athletic prowess, physical formidability, attractiveness, and observable cues to health.

Personality is important, too. Is a partner energetic, dependable, ambitious, emotionally stable, sociable, easy-going or dominant? Most of these qualities change over time. Social status can rise or fall. Health and wellbeing rise and fall day-to-day, but can also be impaired more permanently by a parasite, disease or injury. Personalities change. Energy levels can ebb with age. Ambition might be sated post-mate selection. Even emotional stability can change due to psychological or physical trauma. PTSD is a common consequence of the ordeals of war and sexual assault. Changes in these key components of mate value, inevitable in all but the most insulated lives, must be monitored.

A partner’s mate value is critically also a function of how much they value you. The technical term is welfare-trade-off ratio (WTR), the ratio of how much value they place on your welfare relative to their own welfare. Some mate selectors suffer a rude shock when a high WTR during the courtship phase turns into a selfishly skewed WTR after the wedding vows. This might be one reason why divorce is most common in the first few years of marriage, and then tapers off over time. A partner who initially shows high investment might curtail that investment over time. Relationship satisfaction, a barometer that goes up and down with the tides of time, is the key psychological monitoring mechanism that tracks components of a partner’s mate value, their level of investment, and the WTR they hold with respect to you.

Mate value within couples is inherently relative. Consequently, monitoring a partner’s mate value is not enough. Self-assessment is required. A woman’s or man’s mate value can increase over time. Either person might rise in status, inherit a bounty of resources, or distinguish themselves through acts of bravery, leadership or wisdom, rendering them more desirable on the mating market. A woman whose mate value increases can find herself dissatisfied with her husband, even if his overall desirability has remained unchanged.

Women high in attractiveness elevate their mating standards, expecting higher levels of mate qualities on metrics such as status, resources, commitment, and cooperativeness. A woman’s mate value even varies over the monthly ovulation cycle. To the degree that a woman’s mate value is a function of her fertility, she becomes more desirable around ovulation than at other phases of her cycle. Subtle changes in women’s attractiveness reflect these ovulation shifts. Their skin glows a bit more, their waist-to-hip ratio becomes slightly lower, and their voices rise a bit, all qualities found to enhance perceptions of female beauty. The fact that women become more exacting in their mate preferences at precisely this time in their cycle might reflect an adaptation to monitor their own mate value and adjust their standards accordingly.

According to the mate-switching hypothesis, scanning for alternative mates remains activated even in happy relationships

We do not know whether these cyclical or more enduring changes in women’s desirability influence qualities such as their level of satisfaction with their current partner, their attraction to alternative potential mates, their effort to cultivate back-up mates, or their temptation to have an affair. But there is tantalisingly suggestive evidence. One study found that women are most likely to evade their partner’s mate-guarding efforts precisely around their most fertile phase – an effect most pronounced among women partnered with men low in attractiveness. These women find themselves more interested in attending social events, perhaps because they might interact with alternative mates. And they report engaging in greater flirtation with men other than their regular partner. These findings point to the possibility that women monitor their own mate value, and when it increases, alternative mates can seem more attractive. This, in turn, requires monitoring alternative possible mates.

According to the mate-switching hypothesis, scanning for alternative mates remains activated even among those in happy relationships. Sometimes that tracking occurs at low levels when newly available mates appear or when a potential mate’s attraction or interest increases. Sometimes it gets activated at high levels, as when a woman becomes increasingly dissatisfied with her regular mate and wants out of the relationship.

Our studies, led by the psychologists Daniel Conroy-Beam at the University of California at Santa Barbara and Cari Goetz at California State University San Bernardino, suggest that women tracking alternative mates operate in three dimensions. The first is interest: does the potential mate show attention, attraction and desire? Prolonged eye contact, selective smiles and sideways glances are some documented indicators here. Do these indicators signal long-term interest or a fleeting sexual desire? Many women are reluctant to leave their regular partner for a passing fancy, although some see it as an important signal that something is seriously wrong in their regular relationship. The second dimension is mate value: only large increments in value over the committed partner are likely to be worth the costs of breaking up. The third dimension for tracking is eligibility: is the interested alternative actually free of encumbering commitments such as an existing spouse or crushing obligations to dependent children? Conroy-Beam, Goetz and I also found that women scaled back on the effort to retain their regular partner only when operating in one or more of the dimensions above.

These classic, widespread patterns would never have evolved without producing real-world mating decisions and behaviour. So how do women actually implement a potential mate-switching strategy? We propose three key strategies – cultivating back-up mates, implementing affairs, and enacting a break-up.

One woman told me: ‘Men are like soup; you always want to have some on the back burner.’ The back-up mate hypothesis contends that even people experiencing relatively high relationship satisfaction benefit from cultivating back-up mates because nothing in life or love comes with a guarantee. Our studies on this, led by the psychologist Joshua Duntley at the Richard Stockton College of New Jersey, find that both women and men report cultivating back-up mates – potential replacements for their current mate should their relationships implode. On average, both sexes list having roughly three potential back-up mates. People also report that they would be upset if their back-up mate became seriously involved romantically with someone else. Interestingly, women are more likely than men to report that they would be upset if their back-up entered a long-term relationship or fell in love with someone else. Women more than men report that they would actively try to prevent their back-ups from marrying someone else. The implication seems clear – a back-up mate’s deep mating involvement with someone else undermines their value as an actual back-up mate.

Sometimes, opposite-sex friends serve as back-ups. Women more than men prioritise economic resources and physical prowess in their opposite-sex friends – gender differences that mirror precisely the sex differences in long-term mate preferences. But can the qualities women value in an opposite-sex friend and in a long-term mate be nearly identical by sheer coincidence? A key prediction from the mate-switching hypothesis is that women will ramp up their efforts to solidify opposite-sex friends as potential back-ups when circumstances suggest that a mate switch is on the horizon.

Another clue is that people rarely reveal to their regular partners that they consider someone a back-up mate. ‘We are just friends’ is a common refrain. But being ‘just friends’ is also a tactic used by poachers trying to lure someone away from a long-term mateship. Back-up mates often conceal their own mating motivations.

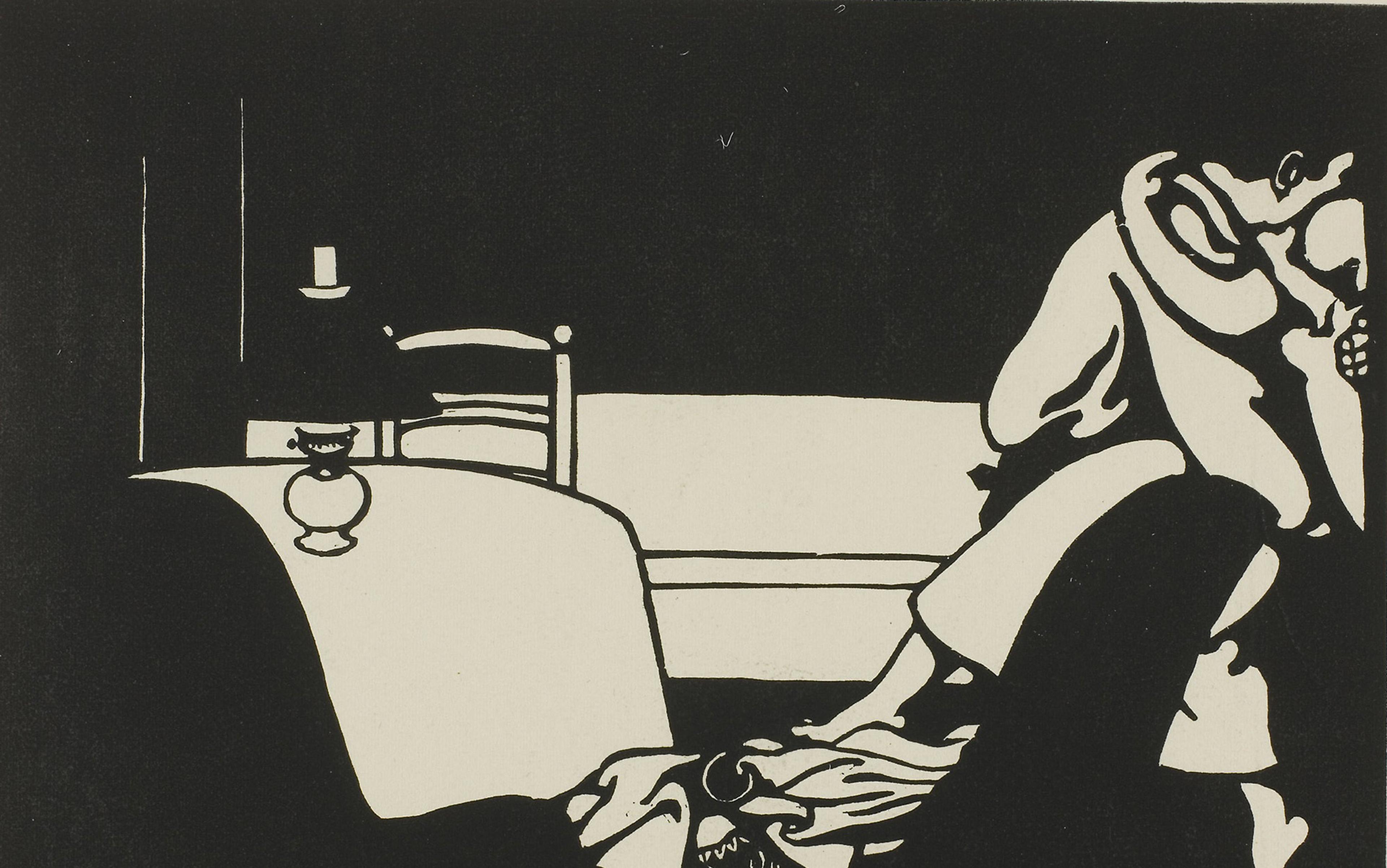

It might disturb a man to realise that his wife carries a mate-insurance policy, harbours sexual fantasies about her co-worker, or has ‘just a friend’ who is his rival

This makes sense. Infidelity is an effective tactic for prompting a divorce, but it is also dangerous. In fact, infidelity is the leading cause of intimate partner violence, and is also a key motive behind spousal murder. Despite these risks, about a quarter of women still take the plunge. Interestingly, married women in their early 30s are most likely to have an affair, perhaps reflecting a motivation to switch mates while their desirability is still high.

A few lines of evidence support the notion that infidelity serves a mate-switching function for women. First, women who initiate affairs are much more likely to suffer from marital dissatisfaction than women who do not. This might seem blindingly obvious, but the same studies show that men who have affairs do not, in fact, differ from those who abstain from affairs in their levels of marital happiness. Second, women are much more likely than men to become emotionally involved with, and to fall in love with, their affair partners. Roughly 70 per cent of women report doing so, in contrast to only 30 per cent of men. Moreover, women are more likely to cite emotional involvement as a reason for the affair. Men are more likely to cite pure sexual pleasure. These critical sex differences point to dramatically different functional reasons for male and female infidelity. For women especially, they point to the mate-switching function.

For those seeking to end a current partnership, exiting the mateship is clearly the final step. One clichéd ejection tactic involves saying: ‘It’s not you, it’s me,’ in an attempt to minimise rage-motivated vengeance. A second involves transforming the existing romantic relationship into a friendship, also designed to minimise the ire of the ex. In some cases, women might continue for a time to provide sexual favours to an ex to minimise costs or attempt to direct his sexual attention to other women. The effectiveness of these and other ejection tactics, and the circumstances in which each tactic is deployed, remain to be studied scientifically.

The mate-switching hypothesis explains an array of findings that otherwise remain mysterious. It explains why most people cultivate back-up mates, why desired qualities in opposite-sex friends map on to desired qualities in a long-term mate, and why back-up mates typically fly under the radar of the regular mate. It explains why women become dissatisfied with their existing relationships when there exist available alternatives in the mating pool who are higher in mate value than their regular partners. It provides a cogent explanation for why women are willing to risk so much to have affairs, an enduring evolutionary puzzle because women gain no direct benefits in the currency of reproductive success.

Recognising that humans have evolved a psychology dedicated to mate-switching undoubtedly will be disturbing to many. It might be disconcerting to a man to realise that his wife is carrying a mate-insurance policy, harbours sexual fantasies about her co-worker, or has ‘just a friend’ who is his rival. It might be depressing to realise that you are more replaceable than you knew. It could be disturbing when it dawns on you that your partner’s unhappiness might not be transient and instead portends a hidden plan for exiting the relationship.

But nothing in mating remains static. Evolution did not design humans for lifelong matrimonial bliss. Our ancestors faced a mating world where something could always go wrong. Those who stuck it out through thick and thin might win admiration for their loyalty. But modern humans have descended from successful ancestors who carried mate insurance; who devoted energy to scenario-building, the cognitive simulations of fantasising about possible mates and laying plans for exiting; and who acted on those scenarios when the hidden calculus pointed to the benefits of switching mates.