My best friend in high school was tall, lean and pretty. She had a long neck and luscious dark hair, alabaster skin punctuated by a constellation of beauty marks, and a teeth gap that she flaunted before it was fashionable. She was funny and fierce, smart but not particularly diligent, and more self-assured than me in matters of romance and sex.

I loved her with a passionate intensity that had sensual undertones of which I was only confusedly and intermittently aware. We spent a lot of time together, shared many new experiences, and supported and relied on each other as intimate friends do.

And yet, I also envied her. I envied her for what I thought was her superior confidence, beauty and ease in navigating a difficult world. I would borrow a skirt of hers, and then, casually and without conscious intention to hurt, I would mention that others had found the skirt slutty. We would take our measurements, and I would resent what was to my eyes an undeniable, if hard to articulate, quantitative inferiority.

I now wonder whether she envied me for my permissive parents, my privileged upbringing, my scholastic achievements. I imagine she perceived my unconfessed envy, but we never discussed it or its manifestations.

Our friendship did not survive graduation. We parted ways without quite telling each other why. I grieved that loss for many years, incapable of understanding what had happened. And then the same thing happened all over again, in college. Different friend, same dynamic.

The phenomenon might sound familiar. Advice columns are replete with stories about frenemies and toxic relationships. Most of the time, the advice is asked or given from the perspective of someone who is immune to envy: it is always the other person in the relationship who is guilty of being envious, petty, competitive and jealous. It’s never us.

The social and moral stigma surrounding this emotion is so strong, that we have a hard time confessing to feeling envy, especially when it involves malice and spite, and even more so when it is directed toward people we love.

And yet, the ancient Greeks were already deeply aware of widespread friendly envy. Aeschylus writes: ‘It is in the character of very few men to honour without envy a friend who has prospered.’ Basil of Caesarea concurs: ‘[A]s the red blight is a common pest to corn, so envy is the plague of friendship.’ And it is not just a matter of friendship.

The first murder in the Bible is committed because of envy: Cain kills Abel because he is jealous and envious that God is more pleased by Abel’s offerings than by his own. Murderous sibling rivalry is so archetypical we find it in many different myths and parables: Romulus and Remus, Thyestes and Atreus, Joseph and his brothers, to name just a few examples from Western culture.

While it rarely reaches these peaks of intensity in real life, sibling rivalry is a well-known phenomenon that concerns both boys and girls, and that seems largely unaffected by parental efforts to reduce it (even though parents can exacerbate it). Envy and jealousy characterise sibling relationships notwithstanding the presence of love. As with best friends, affection, appreciation for the other person’s qualities, and sharing an origin, a culture or favoured activities can even increase, rather than diminish, envy.

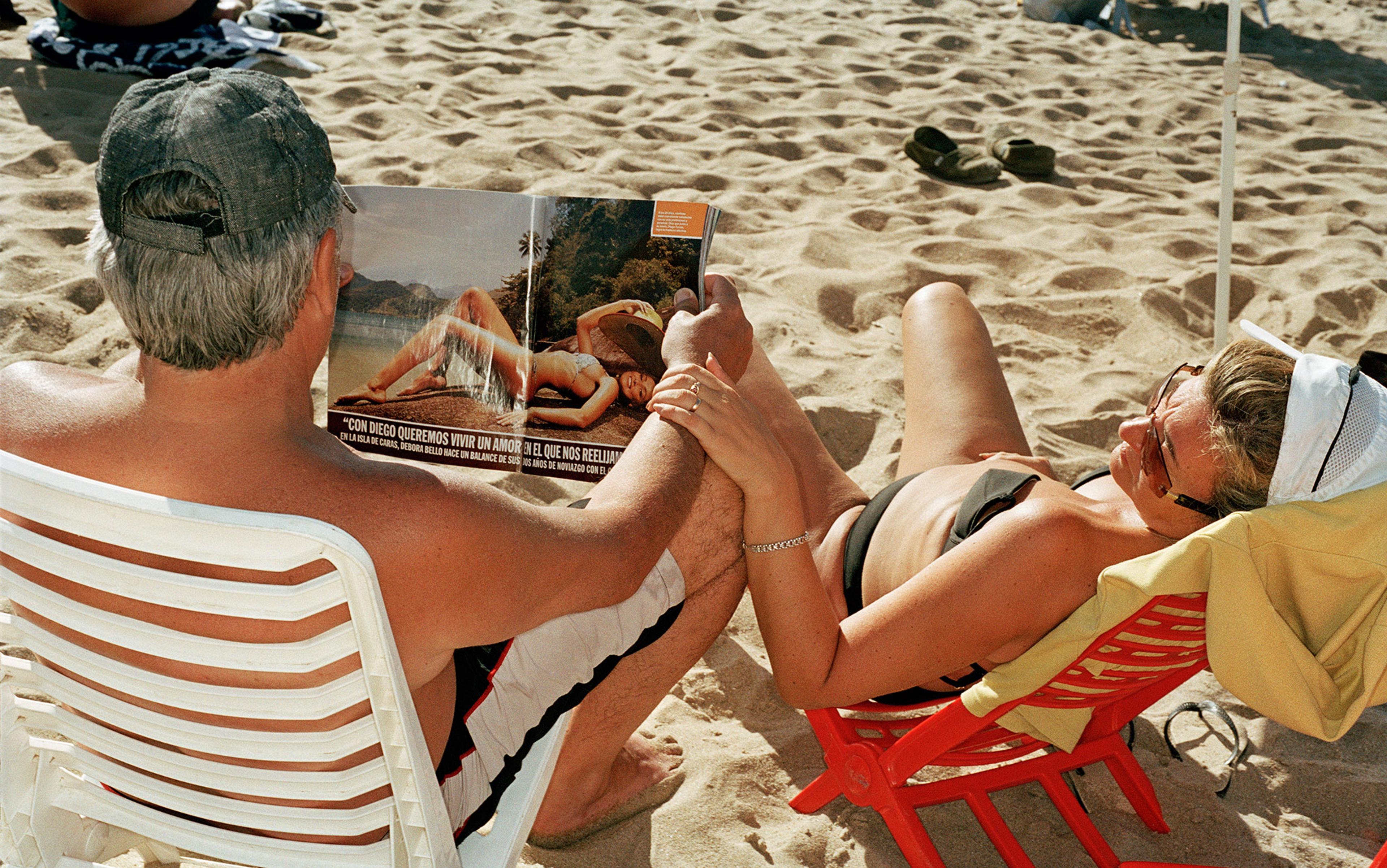

Romantic partners can also feel envy toward one another, especially when they enjoy an equal relationship: in my academic field of philosophy, it is not uncommon for spouses to compete on the job market, sometimes even for the same job, which makes it difficult for the less successful partner to remain supportive of the other.

The greatest taboo of all is envy in the parent-child relationship, which only psychoanalysis, with its emphasis on the unconscious, and literature, behind the veil of fiction, have analysed extensively and without shame.

No love is immune from envy, despite St Paul’s contention that ‘Love does not envy’ (Corinthians 13:4). He is not denying that we sometimes envy our beloved, but is rather pointing to an ideal.

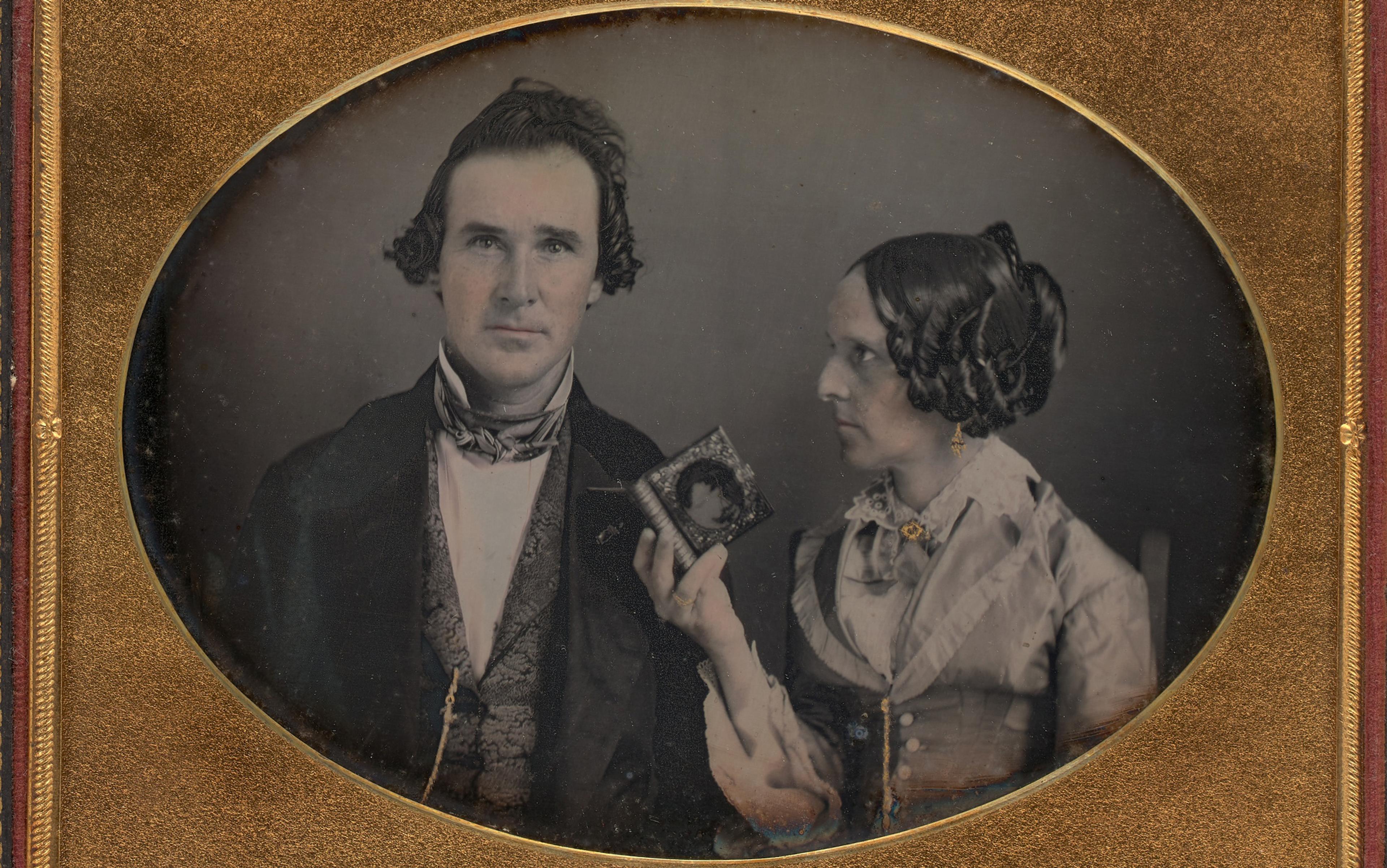

This antithesis between love and envy is visually exemplified in a beautiful Renaissance fresco by Giotto, in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. The fresco features seven pairs of opposing virtues and vices. Envy, a capital sin, is opposed to Charity, one of the three theological virtues. Envy is depicted allegorically as a demonic woman with horns. A snake comes out of her mouth only to blind her, symbolising envy’s ‘evil eye’ and its malicious and counterproductive behaviours. Her ears are huge, because envious people are always alert and curious about other people’s lot. Finally, she holds her possessions with one hand, while her other hand protrudes like a hook, ready to steal from the envied what she lacks. Charity instead seems indifferent to the bags of money lying at her feet; she holds a basket of fruits and grains with one hand, and offers her heart to God with the other.

Christian theology is not unique. Many other religions invite the believer to shun envy, and embrace love. But is that humanly possible?

In his essay ‘Idea for a Universal History with a Cosmopolitan Aim’ (1784), Immanuel Kant compares human beings who accept the hardship of a civic union to trees in a forest: ‘precisely because each of them seeks to take air and sun from the other [they] are constrained to look for them above themselves, and thereby achieve a beautiful straight growth; whereas those in freedom and separated from one another, that put forth their branches as they like, grow stunted, crooked and awry’.

In the essay, Kant discusses two intertwined human tensions: on the one hand, human beings are social animals, driven by benevolence and empathy, capable of self-sacrifice out of love and altruism. On the other, human beings are ferocious beasts, driven by competition and malice and capable of the most atrocious and hateful deeds.

Kant called the juxtaposed human tendencies ‘unsocial sociability’ and, together with other modern philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, sought to explain how it works. Humans derive a deep, highly motivating enjoyment from ‘what is eminent’, as Hobbes puts it in his book Leviathan (1651). They want to be acknowledged by their peers as worthy of esteem and appreciation. They want to be honoured. But honour is unavoidably positional: if we are all honoured, honour loses its value. It requires a ranking, a comparison. Therefore, desire for social esteem is grounded in the tendency to compare oneself to others. This desire is the root of our unsocial sociability.

In the second part of A Discourse on Inequality (1754), Rousseau discusses the paradoxical relationship between love and envy:

[Men] became accustomed to looking more closely at the different objects of their desires and to making comparisons … Whoever sang or danced best, whoever was the handsomest, the strongest, the most dexterous, or the most eloquent, came to be of most consideration; and this was the first step towards inequality, and at the same time towards vice … producing combinations fatal to innocence and happiness.

Rousseau could have been describing high school: people crave to stand out from the crowd as the ‘coolest’ individual and are, in turn, attracted to those who are outstanding. But being the most lovable also means being the most enviable.

Aristotle drilled down on the phenomenon in Rhetoric, observing that ‘we feel [envy] towards our equals … in birth, relationship, age, disposition, distinction, or wealth’. He goes on to explain that ‘we also envy those whose possession of or success in a thing is a reproach to us: these are our neighbours and equals; for it is clear that it is our own fault we have missed the good thing in question.’

Envy arises only when we perceive ourselves as slightly inferior to another, and only with regard to something we care about

Aristotle anticipated a conclusion reached by contemporary social psychology: there can be no envy in the absence of equality between the envier and the envied. Comparing ourselves to others helps us to figure out whether we are talented, beautiful or successful. But, in order for the comparison to be truly informative, it cannot be of the apples-to-oranges sort. If I want to know whether I am a good swimmer, I have to compare myself to other swimmers, not to tennis players. Furthermore, I have to compare myself to swimmers who are roughly my age, gender and skill level, or else the comparison would be skewed. Consequently, envy arises only when we perceive ourselves as slightly inferior to another person, and only in a domain that affects our self-conception, with regard to something that we care about.

An amateur ballerina will not envy, but rather admire a renowned professional dancer such as Misty Copeland, while she might feel envious of another amateur dancer with whom she takes a class, and who dances more gracefully than she does.

So what happens if the more accomplished ballerina turns out to be the amateur ballerina’s best friend? This is a relevant question. We do envy our beloveds, and the reason is not only that we are drawn to love and envy for the same reasons, but also that love and envy thrive in the same conditions of similarity and equality.

‘Equality and similarity make amity,’ claims Aristotle in his ethical masterpiece, the Nicomachean Ethics. He actually devotes much discussion to the many ways in which being similar is crucial to philia, a Greek term that is often translated as ‘friendship’ but that encompasses a much broader range of modern loving relationships, including the relation between parents and children, and spouses. He talks about being equal in reputation and social status, living in the same time and space, sharing the same background, being similar in talent and competence, and having the same goals and values.

It turns out, then, that the same kinds of equality and similarity that favour philia also favour envy: the same soil is fertile for the weed and the crop, and water and fertiliser cannot promote the growth of one without the other. Imagine our amateur ballerina and her friend: they will enjoy going to the opera together, they will show each other YouTube videos, they will give each other advice when taking ballet masterclasses. But every moment in which they rejoice in each other’s company, in which they share their love for dance and engage in their favourite activity, is also an occasion for envy to rear its ugly head: for one to notice that the other is more talented than she is. Envying the beloved is not just common, but virtually unavoidable.

Is that as bad as it sounds? It is undeniable that envy can poison a loving relationship to the point of breaking it. But not all envy was created equal. Contemporary philosophers and psychologists have argued that envy comes in many varieties, which differ in internal psychological structure, behavioural manifestations and moral value.

The envy represented by Giotto is demonic, like that possessing Lucifer in John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667) and motivating Cain to kill his own brother. In sports, on the other hand, we talk about ‘fair competition’, where competing against one another is perhaps the most effective way to achieve self-improvement. By playing against a superior competitor, we improve our own performance, learn new strategies and techniques, and go beyond our limits. There is empirical evidence that a certain kind of envy is more effective at motivating self-improvement than other emotions, such as admiration.

I believe that the only kind of envy that is appropriate and possibly beneficial in a loving relationship is emulative envy. This form of envy is characterised by a focus on the lack of the envied good as opposed to the envied’s superior position; it is motivated by the sense that one is capable of getting the good. The individual who feels emulative envy looks at the envied not as someone to deprive of desirable and valuable qualities or goods, but as a representation of what the agent herself could be or have, as a model for self-improvement. Emulative envy is still an unpleasant emotion, since, like any kind of envy, it necessarily implies the perception of being inferior to another with regard to something important and valuable. But the pain is assuaged by a shared sense of identity with the beloved and thus permits rejoicing of the other person’s good fortune: it’s a pain mixed with pleasure. Furthermore, emulative envy is forward-looking, optimistic and hopeful, because it involves the belief that one is capable of doing better.

As Kierkegaard said: ‘Admiration is happy self-surrender; envy is unhappy self-assertion’

Emulative envy cannot be satisfied by bringing down the envied to one’s inferior position. It is thus void of the malice or ill-will that afflicts other varieties of envy, and fully compatible with the duties of benevolence that ideal love prescribes.

Of note: emulative envy is different from admiration. The Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard in The Sickness Unto Death (1849) captured their fundamental difference in one pithy sentence: ‘Admiration is happy self-surrender; envy is unhappy self-assertion.’ That is, admiration is a pleasant emotion, similar to awe: we admire a person like we admire a landscape. We are motivated to protect it, rather than to become it. It is an emotion that makes us feel good and that doesn’t involve a comparative judgment. So isn’t admiration a nobler alternative to emulative envy? Not really. Unfortunately, admiration is less likely to arise in the same circumstances of equality and similarity, and less likely to bring the envier up to par.

What happens, then, when emulation is not possible – when two friends are in love with the same person, or when two spouses compete for the same job? Loving relationships can tolerate occasional bouts of malicious envy if lovers understand that loving wisely means accepting, forgiving and forgetting our human flaws.

Those last few lines might sound like arid moral philosophy. So let me end on a different note. Literature is the place where truths about human nature are revealed without being explained, and as a philosopher I am grateful for that, because sometimes our analytical tools fall short, and all we can do is to point to the phenomena.

In the quartet of novels that starts with My Brilliant Friend (2012), Elena Ferrante masterfully illustrates the inescapability of envy in a loving relationship. The novels recount the ‘splendid and shadowy’ friendship between Lila and Lenù, two extraordinary, if humanly flawed, women who grow up in a poor and degraded neighbourhood of Naples in Italy.

Lenù is the narrative voice, and she often talks of both her own envy toward Lila, and Lila’s envy toward her. The very title of the first novel is ambiguous: until the end, it is unclear who ‘the brilliant friend’ is. Since Lenù is the narrator who recounts how much she admires her friend, it is natural to think that the brilliant friend is the amazingly gifted and seducing Lila, the woman who has overcome poverty, loss and physical and emotional abuse of every kind. But, as the story develops, we realise as well that Lila considers Lenù, who has become a successful writer, the brilliant one.

By the novel’s end, the reader can see that they are both the brilliant friend – that this is precisely the point, and why the story is so riveting, and their friendship so resilient, notwithstanding the many challenges, conflicts and fractures it endures.

Both women manage to live far more meaningful, richer lives than those of their neighbourhood counterparts. Neither one could have achieved such a result without the other. From the very start, when they are little girls, Lila and Lenù prod and spur each other to do better, and they never stop. They compete throughout their lives not just on professional grounds, but also in the romantic sphere, unwittingly and resentfully sharing suitors and lovers. Their competition is often implicit, but nevertheless fierce, and occasionally vengeful and mean. Their rivalry even leads Lenù, whose most intimate thoughts the reader can access, to wish that her friend had died, and to believe that Lila’s envy has cursed her own happiness. Their relationship thus undergoes all varieties of envy, even the most spiteful kind. And yet, they also feel the most noble one, which constantly motivates them to become better, stronger, more fulfilled women.

Loving wisely takes rivalry and competition as a chance for shared and authentic improvement

How can their friendship not only benefit from emulative envy, but also survive the wounds of the more malicious kinds? Their deep, intense, passionate, friendly love is wise. Loving wisely involves the cultivation, even if not the full achievement, of virtues such as compassion and unbiased self-reflection: it involves the capacity to feel envy toward the beloved in a way that is not only destructive but also constructive.

Wise love is committed to protecting the loving relationship and making it flourish despite negative, aggressive emotions that might arise. That commitment implies that the lover can even encourage the beloved to feel emulative envy toward her. Envy can be an opportunity for the lovers’, and love’s, growth. When envy is emulative, loving wisely takes rivalry and competition as a chance for shared and authentic improvement, and reciprocal and altruistic support. When it is not emulative (such as when Lenù wishes Lila to lose the good things she has, or even wishes her death), loving wisely implies becoming capable of forgiving and forgetting.

Lila and Lenù are friends, their love a perfect example of philia. But there are other forms of love, and they might require different ways of handling envy. For example, parents are supposed to be role models for their children, and so it is appropriate for them to adopt an explicitly pedagogic attitude in managing their children’s envy. Children might find it more beneficial to adopt a sympathetic and tolerating attitude toward their parents’ envy. Siblinghood allows for more open competitiveness than other relations, and so envy might be dealt with in the spirit of fair and affectionate rivalry. The same holds for friendship, even though female friends, due to internalisation of sororal and nurturing ideals of womanhood, might have a harder time engaging in open and fair competition. Attitudes appropriate to romantic relationships are the hardest to characterise in general terms: some lovers behave like peers, while others have more hierarchical relations; some tolerate ‘Pygmalionesque’ attitudes that others find humiliating. Strategies for dealing with envy should be tailor-made for each relationship, solutions to come not from philosophy but rather, psychotherapy.

When envy is destructive and malicious, it can indeed damage our loving relationships, and corrode the delicate fabrics of which love is composed. But the coexistence of love and envy is the consequence of deeply seated features of human nature. They are expressions of our unsocial sociability. However, once we accept that envy is the dark side of love, we come to see that love is the luminous side of envy. Emulative envy, when infused with wise love, can be not just tolerated but might even contribute to the flourishing of our loves.