There are many things we have come to regard as quintessentially French: Coco Chanel’s little black dress, the love of fine wines and gastronomy, the paintings of Auguste Renoir, the smell of burnt rubber in the Paris Métro. Equally distinctive is the French mode and style of thinking, which the Irish political philosopher Edmund Burke described in 1790 as ‘the conquering empire of light and reason’. He meant this as a criticism of the French Revolution, but this expression would undoubtedly have been worn as a badge of honour by most French thinkers from the Enlightenment onwards.

Indeed, the notion that rationality is the defining quality of humankind was first celebrated by the 17th-century thinker René Descartes, the father of modern French philosophy. His skeptical method of reasoning led him to conclude that the only certainty was the existence of his own mind: hence his ‘cogito ergo sum’ (‘I think, therefore I am’). This French rationalism was also expressed in a fondness for abstract notions and a preference for deductive reasoning, which starts with a general claim or thesis and eventually works its way towards a specific conclusion – thus the consistent French penchant for grand theories. As the essayist Emile Montégut put it in 1858: ‘There is no people among whom abstract ideas have played such a great role, and whose history is rife with such formidable philosophical tendencies.’

The French way of thinking is a matter of substance, but also style. This is most notably reflected in the emphasis on rhetorical elegance and analytical lucidity, often claimed to stem from the very properties of the French language: ‘What is not clear,’ affirmed the writer Antoine de Rivarol in 1784, somewhat ambitiously, ‘is not French.’ Typically French, too, is a questioning and adversarial tendency, also arising from Descartes’ skeptical method. The historian Jules Michelet summed up this French trait in the following way: ‘We gossip, we quarrel, we expend our energy in words; we use strong language, and fly into great rages over the smallest of subjects.’ A British Army manual issued before the Normandy landings in 1944 sounded this warning about the cultural habits of the natives: ‘By and large, Frenchmen enjoy intellectual argument more than we do. You will often think that two Frenchmen are having a violent quarrel when they are simply arguing about some abstract point.’

Yet even this disputatiousness comes in a very tidy form: the habit of dividing issues into two. It is not fortuitous that the division of political space between Left and Right is a French invention, nor that the distinction between presence and absence lies at the heart of Jacques Derrida’s philosophy of deconstruction. French public debate has been framed around enduring oppositions such as good and evil, opening and closure, unity and diversity, civilisation and barbarity, progress and decadence, and secularism and religion.

Underlying this passion for ideas is a belief in the singularity of France’s mission. This is a feature of all exceptionalist nations, but it is rendered here in a particular trope: that France has a duty to think not just for herself, but for the whole world. In the lofty words of the author Jean d’Ormesson, writing in the magazine Le Point in 2011: ‘There is at the heart of Frenchness something which transcends it. France is not only a matter of contradiction and diversity. She also constantly looks over her shoulder, towards others, and towards the world which surrounds her. More than any nation, France is haunted by a yearning towards universality.’

This specification of a distinct French way of thinking is not rooted in a claim about Gallic ‘national character’. These ideas are not a genetic inheritance, but rather the product of specific social and political factors. The Enlightenment, for example, was a cultural phenomenon which spread rationalist ideas across Europe and the Americas. But in France, from the mid-18th century, this intellectual movement produced a particular type of philosophical radicalism, which was articulated by a remarkable group of thinkers, the philosophes. Thanks to the influence of the likes of Voltaire, Diderot and Rousseau, the French version of rationalism took on a particularly anti-clerical, egalitarian and transformative quality. These subversive precepts also circulated through another French cultural innovation, the salon: this private cultural gathering flourished in high society, contributing to the dissemination of philosophical and artistic ideas among French elites, and the empowerment of women.

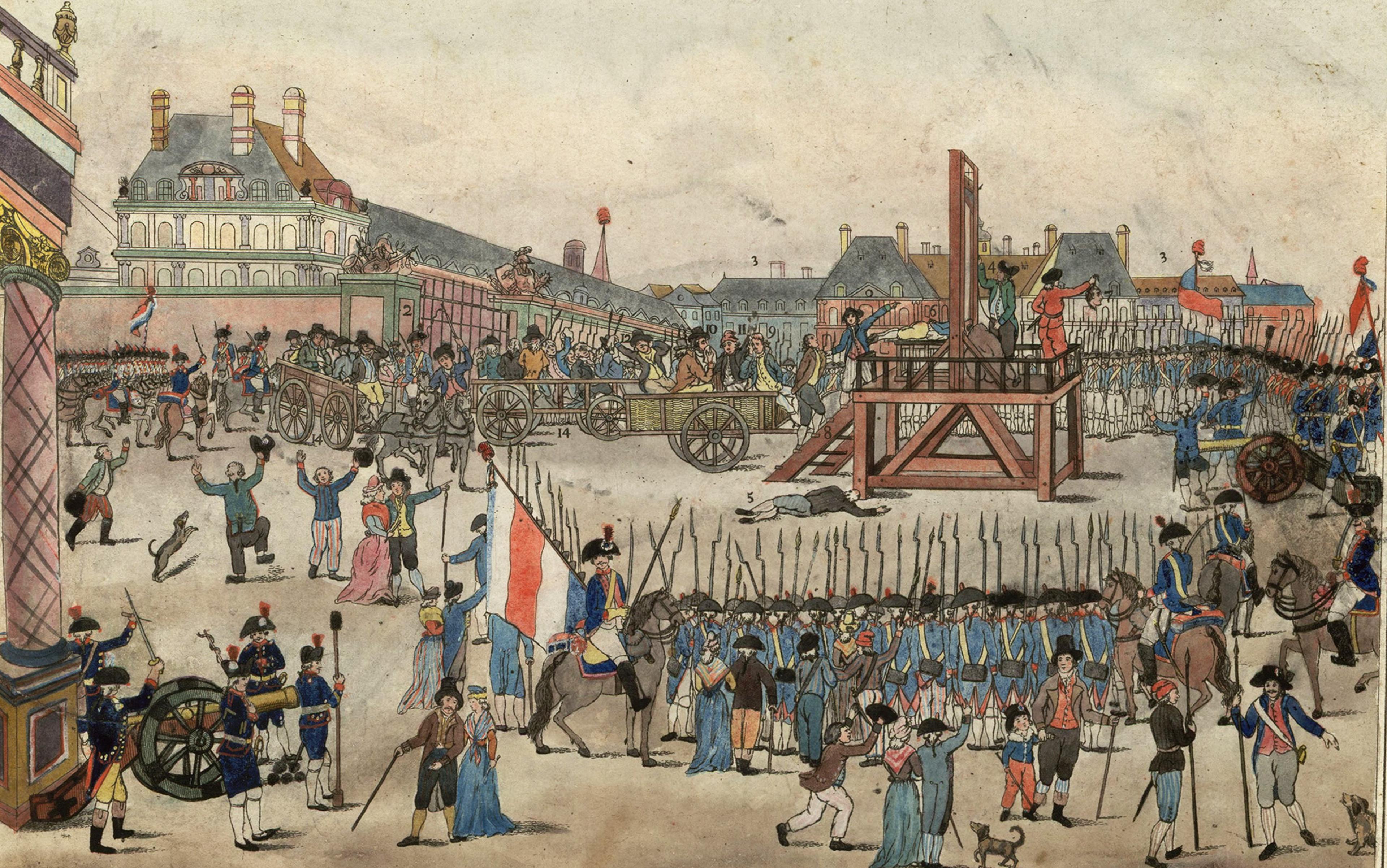

This intellectual effervescence challenged the established order of the ancien régime during the second half of the 18th century. It also gave a particularly radical edge to the French Revolution, compared, notably, with its American counterpart. Thus, 1789 was not only a landmark in French thought, but the culmination of the Enlightenment’s philosophical radicalism: it gave rise to a new republican political culture, and enduringly associated the very idea of Frenchness with novelty and resistance to oppression. It also crystallised an entirely original way of thinking about the public sphere, centred around general principles such as the ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man’, the civic conception of the nation (resting on shared values as opposed to blood ties), the ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity, and the notions of the general interest and popular sovereignty.

One might object that, despite this common and lasting revolutionary heritage, the French have remained too diverse and individualistic to be characterised in terms of a general mind-set. Yet there are two decisive reasons why it is possible – and indeed necessary – to speak of a collective French way of thinking. Firstly, since the Enlightenment, France has granted a privileged role to thinkers, recognising them as moral and spiritual guides to society – a phenomenon reflected in the very notion of the ‘intellectual’, which is a late-19th-century (French) invention. Public intellectuals exist elsewhere, of course, but in France they enjoy an unparalleled degree of visibility and social legitimacy.

Secondly, to an extent that is also unique in modern Western culture, France’s major cultural bodies – from the State to the great institutions of secondary and higher education, the major academies, the principal publishing houses, and the leading press organs – are all concentrated in Paris. This cultural centralisation extends to the school curriculum (all high-school students have to study philosophy up to the baccalauréat), and this explains how and why French ways of thought have exhibited such a striking degree of stylistic consistency.

The French way of thinking has been remarkably fertile. One of the striking measures of this success is the extent to which French ideas have shaped the values and ideals of other nations and peoples. Versailles in the age of the Sun King was the unrivalled political and aesthetic exemplar for European courts, in the same way as the French Revolution, by virtue of its equation of monarchy with tyranny, and its celebration of civic equality, became an inspiration for progressives all over the world during the 19th century and beyond. The Russian Bolsheviks were notably obsessed by the analogies between their revolution and its French predecessor.

At the same time, thanks to its colonial empire (the second largest in the world after Britain’s), France basked in its great-power status and projected its ‘civilising mission’ across its Asian and African dominions. The Statue of Liberty, which has become such an emblem of Americanness, was designed by the French sculptor Frédéric Bartholdi in 1879; to this day Poland’s national anthem celebrates Napoleon Bonaparte; and Brazil’s flag bears the motto of Auguste Comte’s positivist philosophy: order and progress.

Modern French literature, from Flaubert, Balzac and Hugo to Camus, has become an integral part of the Western cultural heritage. In the second half of the 20th century, Jean-Paul Sartre became a global symbol of the intellectual who dared speak truth to power in all its forms, while Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1949) revolutionised our understanding of the feminine condition. A few decades later, ‘French theory’ reshaped the contours of US academia, and Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida and Pierre Bourdieu remain to this day among the most cited thinkers in the social sciences.

One of the main reasons for this global appeal was the dynamism of French thinking. The sheer inventiveness of Gallic thinkers reflects the key role devolved to imagination, alongside reason, in modern French thought; and a corresponding contempt for empirical knowledge: Rousseau begins his Discourse on the Origin of Inequality (1754) by ‘laying aside all facts’. Hence the tendency for French thinkers to push their ideas to their extreme conclusions, and the primacy given to intellectual creation and cultural innovation. Key concepts such as ideology and engagement are French inventions, and the idea of rupture is central to French intellectual discourse. Derrida was thus one of the most recent of a long tradition of French thinkers when he asserted in 2001: ‘There is no ethical responsibility, no decision which is worthy of its name which is not, in its essence, revolutionary, which is not in rupture with the system of dominant norms, or even with the very idea of normativity itself.’

This inventiveness also appears in the establishment of such powerful overarching frameworks as republicanism, positivism, socialism, existentialism and structuralism, and in the Gallic fondness for combining apparently contradictory concepts. ‘Never were we more free than under the German occupation,’ said Sartre at the end of the Second World War, and this French love of paradox has also given us mystical rationalists, conservative revolutionaries, secular missionaries, republican monarchs, and (most wondrous of all) the concept of the glorious defeat.

French thought proved compelling, too, because of its remarkable boldness. This quality was expressed in the richness of the French utopian tradition, which began with Rousseau, reached its apogee in the 19th century in the irenic works of socialists and Saint-Simonians, and later culminated in the communist tradition. This boldness was also reflected in the extraordinary intellectual ambition to provide ‘total’ explanations of human phenomena – a common trait of Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert’s 18th-century Encyclopédie, Comte’s 19th-century positivism, and the 20th-century Annales historians’ methodology, whose self-proclaimed objective was to produce a ‘total history’.

French rationalism is charged with creating a nation of individualists, with a fetish for skepticism and challenging authority

This French style of thinking has had its critics, both from within France and outside. The liberal thinker Alexis de Tocqueville noted in 1856 the ‘extraordinary and terrible’ influence of literary figures in France, lamenting their disposition to ‘indulge unreservedly in ethereal and general theories’ in order to ‘rebuild society on some wholly new plan’. Making the same point in philosophical terms in 1901, the essayist Hippolyte Taine criticised Descartes and Rousseau, France’s tutelary thinkers, for shying away from experience, and creating a formal mode of reasoning that relied only on the deductive method and on essentialist abstractions such as ‘human nature’.

Likewise, Foucault criticised the French philosophical obsession with Reason for its sweeping character, and for effectively clearing the way for new, and more perverse, forms of social and political oppression. Indeed, Foucault believed that the imperatives of control and domination lay at the heart of the Enlightenment’s conception of rationalism: it was thus less concerned with liberating the mind than with imposing a bourgeois order of ‘pure morality and ethical uniformity’. It was a similar intuition that led Frantz Fanon to urge his comrades struggling for freedom from colonial rule during the post-Second World War-era to reject the false universalism of ‘the European model’, which was nothing but ‘the negation of humanity’.

In less apocalyptic terms, French philosophical rationalism has also been charged with creating a nation of individualists, with a crippling fetish for skepticism, and for challenging authority in all its forms. This trait has been deemed to have negative consequences of both a practical and theoretical nature. In the latter case, it has fostered a tradition of theoretical extremism (most vividly reflected in the vibrant radical movements in France both on the right and the left). It has hindered the emergence of a gradualist epistemological tradition of acquiring knowledge through a process of accumulation. And in practical matters, this French individualism has encouraged a cult of singularity and a resistance to state power: President Charles de Gaulle (himself one of France’s great individualists) gave voice to this concern when he once wondered whether it was possible to govern a country that produced 246 varieties of cheese.

Since the late 20th century, the rich tradition of French thought has come under increasing strain. The symptoms of this crisis are numerous, beginning with a widespread belief in the decline of French artistic and intellectual creativity. In 2007, Time magazine’s cover article even announced ‘The Death of French Culture’, cruelly concluding: ‘All of these mighty oaks being felled in France’s cultural forest make barely a sound in the wider world.’ Even philosophical ideas about resisting tyranny and promoting revolutionary change, which were the hallmark of French thought since the Enlightenment, lost their universal resonance. It is instructive that neither the fall of Soviet-style communism in eastern Europe or the Arab spring took any direct intellectual inspiration from French thinking. The European project, the brainchild of French thinkers such as Jean Monnet, has likewise stalled, as European peoples have grown increasingly skeptical of an institution that appears too distant and technocratic, and insufficiently mindful of the continent’s democratic and patriotic heritages.

Mirroring this retrenchment is a pervasive mood of pessimism that has spread across the French nation. In opinion polls since the early 21st century, the French have appeared consistently gloomy about their future prospects as a nation. French thinking has become increasingly inward-looking – a crisis that manifests itself in the rise of the xenophobic Front National, which has become one of the most dynamic political forces in contemporary France, and in the sense of despondency among the nation’s intellectual elites. It is no accident that two of the bestselling pamphlets of the recent past have been Alain Finkielkraut’s L’Identité malheureuse (2013) and Eric Zemmour’s Le suicide français (2014), and that Michel Houellebecq’s latest dystopian novel about the election of an Islamist candidate to the French presidency bears the resigned title of Soumission (‘submission’) (2015).

A telling example of this crisis of French thought is the discussion of the integration of post-colonial minorities from the Maghreb – one of the burning issues in contemporary French politics. The roots of this question lie in the universality of the French model of citizenship, and the deeply held assumption of the beneficial quality of French civilisation for humankind. Because of their belief in the emancipatory quality of their culture, French progressives consistently advocated a policy of assimilation in the colonies, and largely ignored the racism and social inequalities produced by their own empire. This uncritical belief in the supremacy of the French mission civilisatrice was illustrated during the Algerian war of national liberation in the 1950s and early ’60s by the socialist Guy Mollet, who rejected all manifestations of Algerian nationalism as ‘reactionary’ and ‘obscurantist’.

This colonialist legacy still casts a long shadow over the ways in which France treats and perceives its ethnic minority citizens, especially those from the Maghreb. Because of their rejection of ‘communitarian’ group identities in the British or American mould, the French have no generic way of even designating these minority groups (the only available word is the slang term beur), except to refer to their country of origin. Even worse, these minorities are regularly demonised in the French conservative press and by the extreme right. This vilification has been made easier by the typically abstract and binary ways that French thinkers have framed the debate about minority integration. Thus the principle of laïcité (secularism) has been deployed not to protect the religious freedom of the Maghrebi minorities, but to question their Frenchness.

the Gallic malaise highlights the erosion of the classical strengths of French thinking (universalism, dynamism and inventiveness)

The Muslim veil (hijab) has been banned in French schools, and those who have opposed this measure have been spuriously accused of ‘communitarianism’ and ‘Islamism’ – terms all the more terrifying in that they are never precisely defined. Since the January 2015 attack on Charlie Hebdo, there have been widespread calls for French citizens of Maghrebi origin to ‘prove’ their attachment to the nation. Presenting the issue of civic integration in such schematic terms has proved socially divisive, not least because it has detracted from the real problems confronting these populations: unemployment, racial discrimination, and educational underachievement.

The French fondness for abstraction appears in its most paradoxical (and perverse) form in the absence of precise statistical information about their Maghrebi minorities, as it is illegal to collect data about ethnicity and religion in France (an article on the front page of Le Monde this August stated that France has ‘between 2 and 5 million Muslims’). And so, in the absence of specific social facts and trends, the debate about minority integration has become mired in crude ideological oversimplifications: the equation of secularism with Frenchness (even though the 1905 law separating church and state has never been implemented in some parts of France, such as Alsace-Moselle); the suggestion that the white secular French are the bearers of ‘reason’, while those who practise the Islamic faith are ‘reactionary’ (the very same argument deployed earlier against any natives who dared to question French colonial rule); and the essentialist assumption of an immutable, and yet paradoxically-fragile, French ‘national identity’.

The present Gallic intellectual crisis is in part an anguished collective reaction against France’s shrinking place in a world increasingly dominated by Anglo-American culture. Indeed, this penetration has now advanced deep into the French heartlands: Disneyland Paris is one of the most visited theme parks in Europe; translations of US and UK novels routinely feature on French bestseller lists; and to the dismay of many of the nation’s intellectual elites, the French government recently voted a law allowing French universities to teach certain courses in English. The global retreat of French cultural institutions is also apparent in the low ranking of the nation’s elite universities in the Shanghai league table, and the generally recognised impotence of official organisations such as Francophonia, the association of French-speaking countries, which does little except hold lavish annual summits of its heads of state.

In intellectual terms, the Gallic malaise also highlights the erosion of the classical strengths of French thinking (universalism, dynamism and inventiveness), and the preponderance of its less salubrious features: an over-reliance on abstraction, and a fetish for semantics (one of the most perverse legacies of the post-structuralist flourish of the late-20th century, typified by the works of Foucault, Derrida, Gilles Deleuze and Jean Baudrillard); a tendency to look inwards in space, and backwards in time, and to retreat within the comfortable boundaries of disciplinary specialisations. As the leading historian Pierre Nora said in an interview with Le Figaro this May, French thought is increasingly suffering from ‘national provincialisation’.

The humanism of the republican tradition is still alive, and pushing back against the pessimism of the declinists

All of these negative elements are fused in the current mainstream discussion of French identity, which stems from the refusal of the nation’s elites to adapt their rhetoric to the reality of a multicultural and postcolonial French society. This resolute and often dogmatic attachment to a unitary sense of the French collective self is also one of the powerful legacies of Descartes’ conception of philosophical reason. This ideal (echoed in the classic concept of the ‘one and indivisible republic’) remains widespread among French intellectual elites today. As the editor of the daily newspaper Libération Laurent Joffrin put it in an article this April: ‘Only an abstract conception of Man can confer unity upon France.’

Yet there are silver linings to this bleak vision. The humanism and intellectual creativity of the republican tradition is still alive, and indeed is increasingly pushing back against the pessimism of the declinists. Such voices can be heard in the progressive press, notably in the powerful pamphlet by the journalist Edwy Plenel Pour les musulmans (2015), an eloquent demonstration that multiculturalism is in fact an integral (albeit unrecognised) part of France’s cultural heritage; in the sociological theories of Bruno Latour, whose research effectively combines grand theory with epistemological pluralism; and in Thomas Piketty’s acclaimed study of the inherently inegalitarian nature of modern capitalism, which was hailed by the Nobel Prize-winning US economist Paul Krugman as ‘a book that will change both the way we think about society and the way we do economics’.

Indeed, there are wider grounds for optimism. The French are still exceptionally devoted to their culture, to an extent that is unique in the Western world. France remains the land of major cultural festivals (more than 3,000 are held every year, mostly during the summer); the Journées du Patrimoine draw more than 12 million annual visitors to the country’s historical sites; the Ministry of Culture provides subsidies to a wide range of cultural activities, from artistic endeavours and research institutes to regional bookshops. Most importantly, the French still idolise their major writers, and remain a nation of avid readers, across all age groups and occupations. The Rentrée Littéraire is a cherished literary ritual every September, and for the 2015 season no fewer than 589 new novels are expected.

Among the runaway early successes is Laurent Binet’s La septième fonction du langage, an entertaining murder-mystery yarn framed around the death of the philosopher Roland Barthes in 1980. Its subtle lampooning of the vanities of late-20th-century Parisian high culture should be read as a satire of the structuralists’ interpretative delirium, but also as a belief in the possibility of a return to the universalising rationalism of the French intellectual tradition. Regeneration, after all, is one of the most potent ideals of modern French culture.

Sudhir Hazareesingh’s book How the French Think: An Affectionate Portrait of an Intellectual People is published in the US on 22 September 2015.