Like the great entrepreneurs who came before him, Elon Musk’s life story reads like myth. Or maybe a comic book. He was a precocious child of extreme intelligence who read the encyclopedia for fun; not surprisingly, he was picked on relentlessly. Bullies once pushed him down a flight of stairs and beat him so badly he ended up in hospital.

But even as a child, he was obsessed with visions of a better future, convinced that he must try to save humanity. Eventually, he identified five possible species-ending threats to mankind, and resolved to address them. The most solvable, in his opinion, was the need for sustainable energy-production, and the need for a backup plan – say, a self-sustaining million-person colony on Mars.

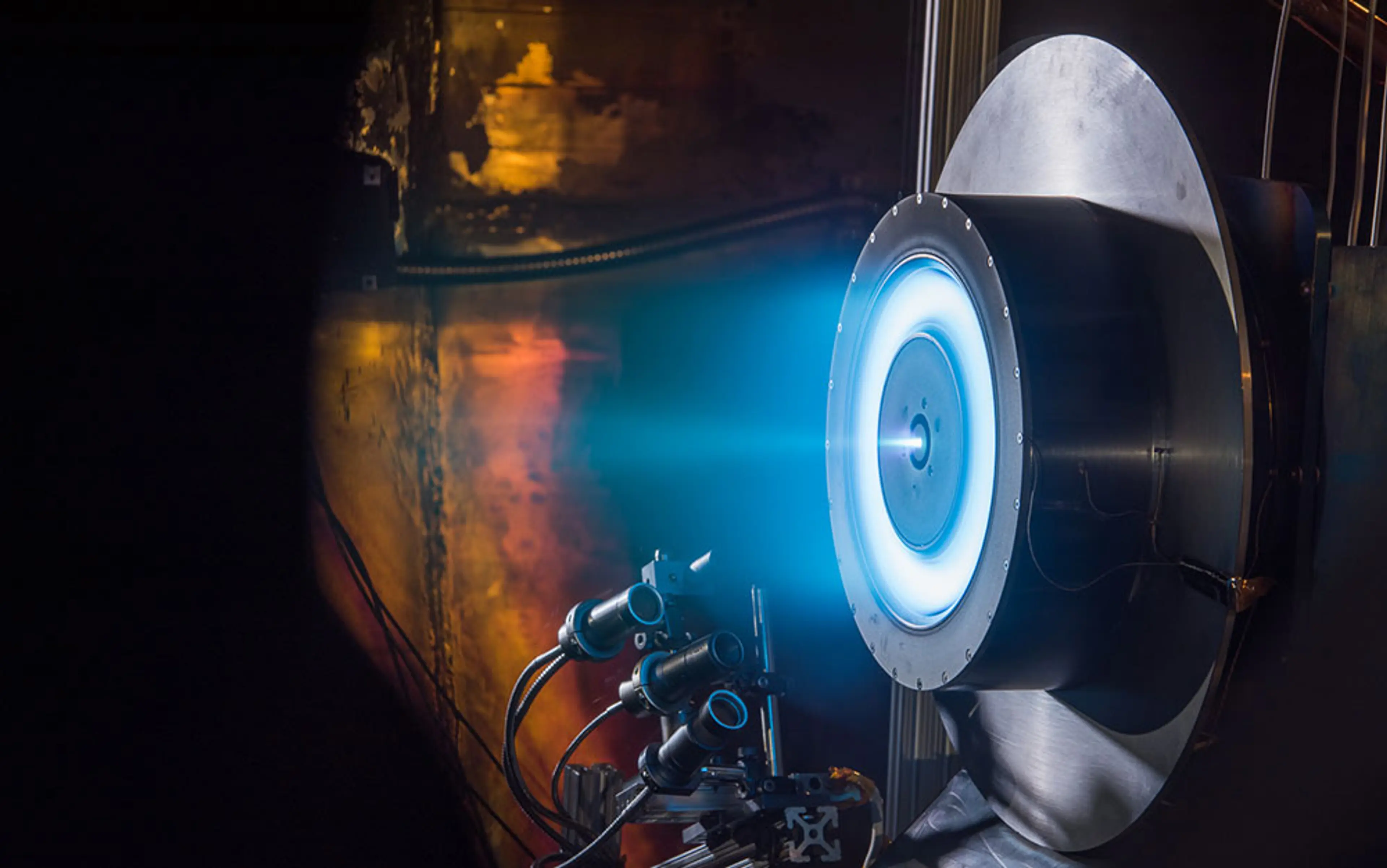

He began implementing this vision seriously in the early 2000s, using a $180 million payout from selling PayPal, his first huge company, to launch the private rocketry firm SpaceX. A few years later, he put millions into the electric car manufacturer Tesla. Car makers and tech people ridiculed his plan to build a high-performance luxury electric vehicle and, eventually, a cheap mass-market version. Everyone else started laughing when the first SpaceX launch vehicle exploded, then another, and then a third.

By 2008, as the financial markets around the world melted down, his plans to save the world through enlightened entrepreneurship were circling the drain. Tesla cars were months behind schedule, and there was enough money only for one more rocket launch. If this rocket exploded too, if the cars didn’t arrive, if the investors didn’t come through, the game was over. Both of his businesses would collapse, and his own fortune would vanish.

Musk says he was on the edge of a nervous breakdown, and then suddenly it all turned around: the launch succeeded, NASA gave SpaceX an enormous contract, the cars were delivered, and today Musk runs two groundbreaking businesses, each worth billions. Now, it’s Elon Musk’s world. We just live in it – until we move to Mars.

In Silicon Valley these days, you haven’t really succeeded until you’ve failed, or at least come very close. Failing – or nearly failing – has become a badge of pride. It’s also a story to be told, a yarn to be unspooled. When a tech startup stumbles or fails, as most of them eventually do, it is customary for the company’s founder to detail how and why it failed.

In fact, it’s become a ritual. Many post-mortems appear on Medium; others are collected at Autopsy.io, a site curating first-person tales of flops, or at FailCon, a convention dedicated to picking apart failures. The stories tend to unfold the same way, with the same turning points and the same language: first, a brilliant idea and a plan to conquer the world. Next, hardships that test the mettle of the entrepreneur. Finally, the downfall – usually, because the money runs out. But following that is a coda or epilogue that restores optimism. In this denouement, the founder says that great things have or will come of the tribulations: deeper understanding, new resolve, a better grip on what matters.

Silicon Valley is a sun-drenched utopia of money and world domination. Tech entrepreneurs are household names. So why the tales of woe, the obsession with darkness overcome? Why are people still preoccupied with Musk’s near-failures, even as they worship his current success? Unconsciously, entrepreneurs have adopted one of the most powerful stories in our culture: the life narrative of adversity and redemption.

Each of us has a story we tell about our own life, a way of structuring the past and fitting events into a coherent narrative. Real life is chaotic; life narratives give it meaning and structure. Studies in the field of narrative psychology suggest that these tales we tell aren’t just a convenient way to describe the past: the way we formulate our own story moulds who we are.

For Americans, the redemption narrative is one of the most common and compelling life stories. In the arc of this life story, adversity is not meaningless suffering to be avoided or endured; it is transformative, a necessary step along the road to personal growth and fulfilment.

For the past 15 years, Daniel McAdams, professor of psychology at Northwestern University in Illinois, has explored this story and its five life stages: (1) an early life sense of being somehow different or special, along with (2) a strong feeling of moral steadfastness and determination, ultimately (3) tested by terrible ordeals that are (4) redeemed by a transformation into positive experiences and (5) zeal to improve society.

This sequence doesn’t necessarily reflect the actual events of the storyteller’s life, of course. It’s about how people interpret what happened – their spin, what they emphasise in the telling and what they discard.

Believing that you have a mandate to fix social problems requires a sense of self-importance, even a touch of arrogance

In his most recent study, the outcome of years of intensive interviews with 157 adults, McAdams has found that those who adopt this line tend to be generative – that is, to be a certain kind of big-hearted, responsible, constructive adult. Generative people are deeply concerned about the future; they’re serious mentors, teachers and parents; they might be involved in public service. They think about their legacy, and want to fix the world’s problems. But generative people aren’t necessarily mild-mannered do-gooders. Believing that you have a mandate to fix social problems – and that you have the moral authority and the ability to do so – also requires a sense of self-importance, even a touch of arrogance.

No wonder that the redemption narrative is so popular in Silicon Valley, where the script of Musk’s life emerges again and again in the stories that founders tell. The Silicon Valley version of the Redemption Story has adapted the format put forth by McAdams with three main chapters that tech founders claim as their own: The Awesome Journey, The Pivot and, finally, Making the World a Better Place.

The founder’s story usually begins with the fun stuff – frantic work, hair-raising scrapes with bankruptcy, and at least one long, dark night of the soul in which the founder is nearly destroyed by doubt. In tech culture, this is called ‘the awesome journey’ (as in ‘It’s been an awesome journey, with tons of learning along the way’) and relentless hours of work; Uber’s CEO Travis Kalanick refers to these as the ‘blood, sweat and ramen’ years. In a talk a few years ago at FailCon, he told the epic tale of the business he founded prior to Uber, and the marathon that kept it alive. He endured two lawsuits, the burst of the first dot-com bubble, a bankruptcy, and months of living at his parents’ house on zero pay. After that, his co-founder defected to Google, stole his main engineer, and scuttled a million-dollar deal. Kalanick’s talk focused on the gory details, which is what his audience wanted to hear. The fact that his startup was eventually acquired was a side note.

The awesome journey is equivalent to the ‘moral challenge’ of the classic narrative. By recapping the hero’s difficulties, it demonstrates his resolve. McAdams describes the theme this way: ‘I am a gifted adventurer who journeys forth into a dangerous world.’ The adversities encountered during this phase are what later unlock the doors to triumph. For entrepreneurs, these are not merely newbie errors. They are cathartic moments of suffering that enable later greatness.

But first, the moment of truth.

It’s a myth that Silicon Valley loves the demoralising experience of failure. So startup postmortems aren’t neutral accounts of what went wrong and why. They promote the idea that failure enables later success.

That’s why tech entrepreneurs refer to failure as a pivot. Originally popularised by The Lean Startup (2011), a guidebook for entrepreneurs, ‘pivot’ has come to mean a moment of reckoning, the moment when one set of plans is abandoned.

People pivot when it becomes obvious that their business plan is too complicated, will never gain traction, has no potential customers, or is just a bad idea. But tech is not like other sectors, where bad ideas merely sink without a trace. People pivot, and they begin again. Pivoting turns failure into rebirth, in which the difficulties and setbacks of the past give rise to a new, stronger, better vision. This is not incremental improvement; it is a transformation. A phoenix rises from the ashes, a door opens, a new vision emerges from the old. In this moment of redemption, the slate is wiped clean.

Obviously, this is a mythos, an outlook rather than a neutral accounting of the facts. In reality, the idea that failure breeds success is empirically wrong, points out the historian Leslie Berlin, who researches the history of innovation at Stanford University. In a Harvard Business School study of thousands of venture-backed companies, those entrepreneurs who succeeded the first time were more likely to succeed again the second. Those who failed once were just as likely to fail again the second time. ‘In other words, trying and failing bought the entrepreneurs nothing – it was as if they never tried,’ Berlin wrote in The New York Times. The narrative device of the pivot sustains hope against this cruel reality.

‘This is what happens when you work to change things. First they think you’re crazy, then they fight you, and then all of a sudden you change the world’

But while faith in the pivot might be delusional, it is a valuable illusion. When people think about their misfortunes as life-changing opportunities, they gain an advantage, McAdams has found. ‘The failures become part of the grand narrative of progress: “That had to happen, and I needed that setback, or I wouldn’t have made this discovery”,’ he says. It keeps morale high. It fosters grit and perseverance. People who tell these stories tend to be more satisfied and feel that their lives are coherent and meaningful. People in McAdams’s interviews said that they turned the bad into good, or found new strength inside themselves. It’s a mindset that encourages resilience, something every entrepreneur needs.

In the redemption narrative, the payoff for steadfastly enduring all the challenges is a fresh opportunity to do good. People told McAdams that they intended to create a better future for their family, community, or society as a whole.

There’s a reason that the idea sounds familiar: it’s become a running joke about the self-importance of tech. In the first season of the HBO spoof Silicon Valley (2014-), one startup founder after another deploys that mantra to convince investors to pump money into esoteric projects. Example: ‘We’re making the world a better place through canonical data models to communicate between endpoints!’

The joke hits home. The iPhone tagline was ‘This changes everything’. In Google’s S-1 – the regulatory paperwork a company submits before going public – an entire section is titled ‘Making the World a Better Place’.

That mentality was perfectly captured in just two sentences by Elizabeth Holmes, the founder of the former Silicon Valley darling Theranos, which is developing an improved blood-testing technology. The company, recently valued at more than $9 billion, abruptly fell from grace in 2015 when it became clear that the technology was not ready for prime time. In her appearance on CNBC, Holmes played the notes of tech redemption: ‘This is what happens when you work to change things,’ she declared. ‘First they think you’re crazy, then they fight you, and then all of a sudden you change the world.’

Sure, it sounds presumptuous, maybe even a bit phoney. The usual assumption is that when people in tech talk about changing the world like that, it’s just a cynical bid for attention. That’s because Silicon Valley has a reputation for selfishness, where vast wealth stays in the pockets of CEOs and founders rather than being diverted toward museums or universities – never mind toward changing the world.

But an essential point about the redemption narrative is that, through the telling, it culminates in a genuine desire to improve the world – and in the case of tech, the conviction that it is possible to do so.

So maybe we’ve got it all wrong about tech. The logic of the redemption narrative predicts that when Musk says that he plans to convert the world to solar power and establish a colony on Mars, he’s entirely sincere, as crazy as he might sound. In a redemption narrative, the will to succeed in business is perfectly compatible with a desire to change the world.

In fact, the idea of doing good by doing well goes back to the early years of Silicon Valley. In his book From Counterculture to Cyberculture (2006), the Stanford historian Fred Turner describes the origins of this train of thought in the late 1960s, when visionaries such as Stewart Brand of the Whole Earth Catalog rubbed shoulders with artists, military-funded cybernetic theorists and commune-builders; the same utopian spirit lives on today at the Burning Man festival in Nevada. For people who belong to this world, it’s self-evident that technical innovators can also solve social problems. It’s taken for granted that entrepreneurialism is the fastest road to a better future.

So it seems possible that in the coming decade, as the tech titans of today hit middle age, the most generative stage of life, they will unleash an unprecedented wave of philanthropy. These optimists, fuelled by vast sums of money and unwavering confidence in their own ability to fix things, might become world-builders on an unprecedented scale. Already we see hints of that: in the efforts of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to eliminate malaria; in Mark Zuckerberg’s efforts to improve schools; in Sean Parker, the founder Napster, pledging $600 million for research into cancer and malaria, among other causes.

Musk is taking that just a few steps further, by hoping to seed other planets with human beings to avert the inevitable extinction of the species. In fact, the launch of SpaceX could be seen as the ultimate act of generativity. Musk says that when he founded the company, he knew the odds were against him. The stakes were just too high. ‘An engineered virus, nuclear war, inadvertent creation of a micro black hole, or some as-yet-unknown technology could spell the end of us,’ he wrote in 2008. ‘Sooner or later, we must expand life beyond our little blue mud ball – or go extinct.’