Three centuries after Christopher Columbus landed in the Americas, Europeans had sailed to the farthest reaches of the Earth, trading in markets as far away as the Americas, Africa and Asia. North Africa, just across the Mediterranean from Europe, was terra cognita. Not only had Europeans fought many wars with North Africans over the centuries, they had established factories, churches and even cemeteries at all the major ports. Still, they were surprisingly unclear about who the North Africans were and how the names they gave them related to those that the people gave themselves. After centuries of calling all North Africans Moors, Europeans didn’t feel the need to change their practice, even when they realised that not everyone they called a Moor thought they belonged together.

‘Moor’ was the name that Europeans had used to describe a variety of North African groups since Roman times. For those who found old designations more compelling, it had the advantage of being very old. It might not have been what North Africans called themselves, but using Moor skipped over the more complicated question of North Africans’ self-identification and the fact that what was known about the ancient Moors came from their Roman masters. When the Arab Muslims conquered North Africa in the 7th century, they used the term ‘Berbers’ to describe those peoples whom the Romans had called Moors, as well as those the Romans called barbarians or something else.

More than 1,000 years later, by the 18th century, the people who inhabited North Africa thought of themselves no longer as Moors but as either Arabs or Berbers. To them, the name of the country that Europeans called Barbary was part of the Maghrib, the Muslim West. Even the Ottomans, who ruled the ‘Barbary states’ of Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli, called it the Maghrib.

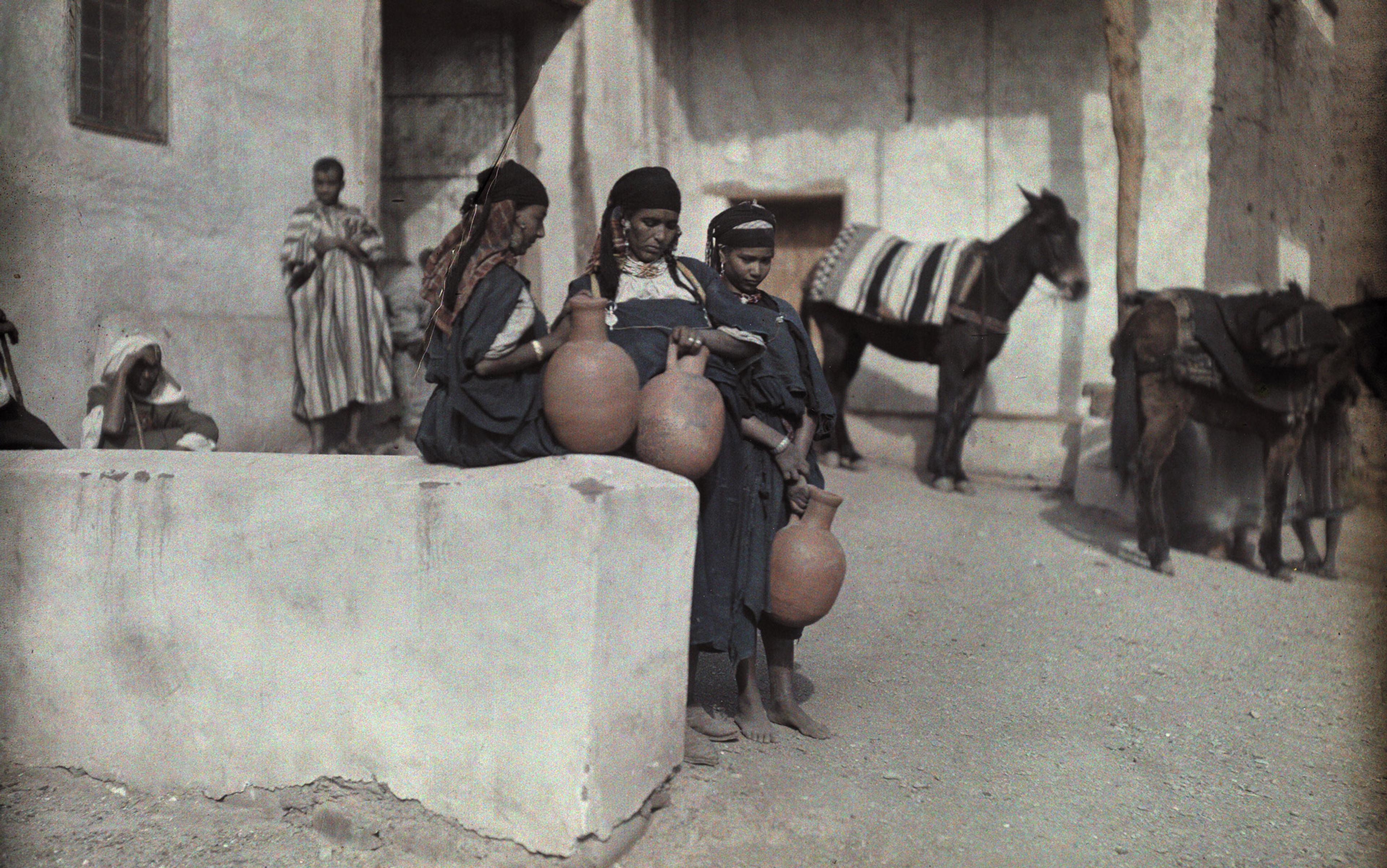

Confusingly, Europeans held on to ‘Moor’ as a name for the people but called the land Barbary, a word they did not imagine had anything to do with Berbers. Over a few decades in the 19th century, the French began to try to sort all this out and to devise a new way of representing the locals, one that adapted native nomenclatures to the project of French colonialism in Algeria. In the process, Barbary gave way to North Africa (Afrique du Nord), Arabs became Oriental Semites, and Berbers became a white race – or at least a non-black one – and the true indigenous inhabitants (indigènes, autochtones) of North Africa.

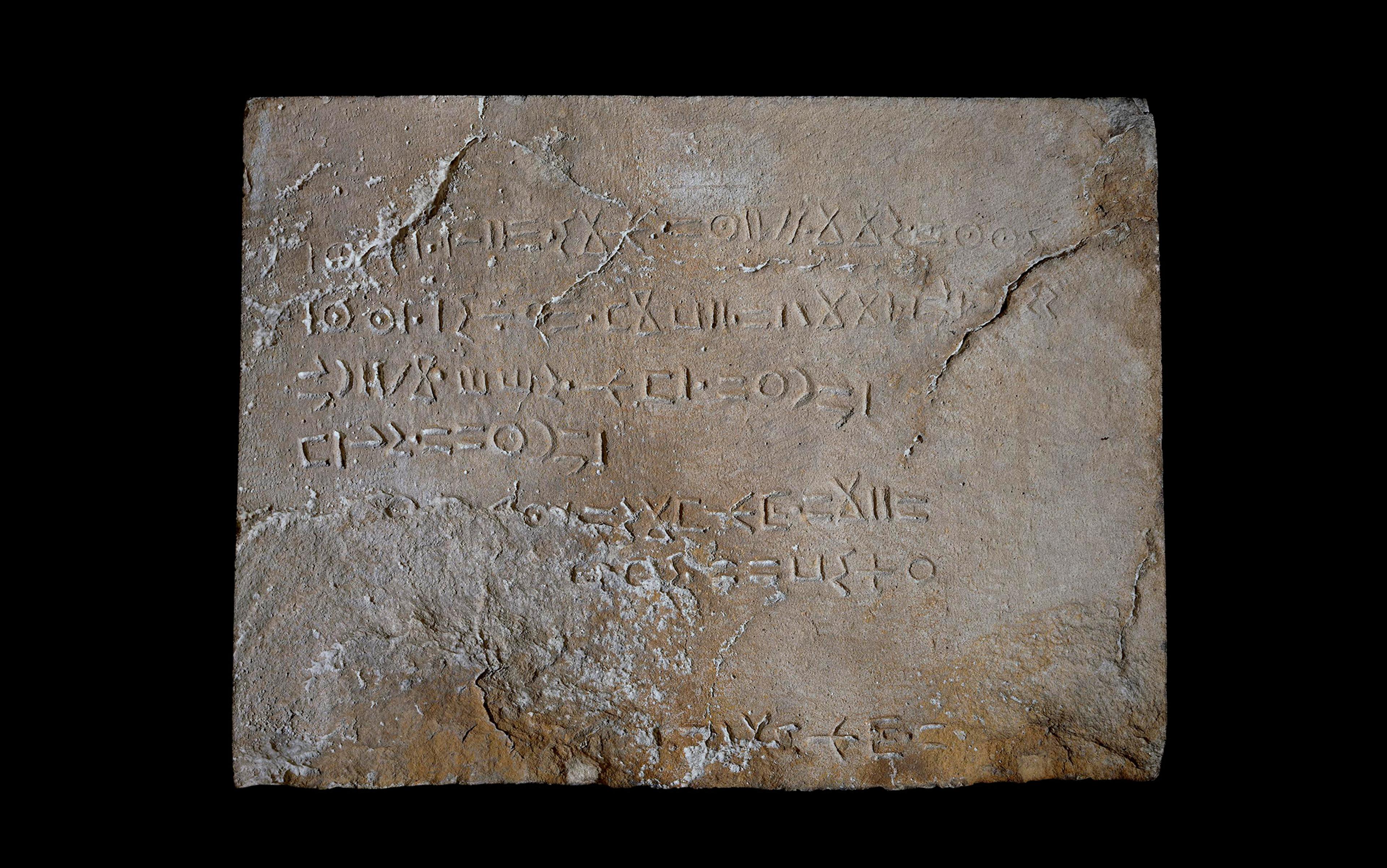

Today, the accepted name for all Berbers from eastern Egypt to the Atlantic is Imazighen (singular: Amazigh, pronounced /ʔa.maːˈziːʁ/), the name of a tribe in central Morocco. Unlike Berber, which evokes ‘barbarian’, the name usually comes with the fanciful but evocative explanation that it is a translation of ‘free men’.

William Shaler, the American Consul General at Algiers, arrived in 1815 to represent the United States in the peace negotiations following the Barbary Wars. During his 10-year stay in Algiers, he socialised with foreign merchants and diplomats, French and Italian mostly, enjoying civilised parties where everyone spoke French and drank French wine. It was from them and a few travelogues that he gathered bits of information about the locals that served as the bases for his book Sketches of Algiers (1826), a work that represents well what Europeans knew about the ‘Barbary coast’.

Shaler’s Sketches gives reliable information on the commercial and military situation of Algeria. It is also filled with inaccuracies, half-truths and misunderstandings about the country and its inhabitants. Like many foreigners in Algiers, Shaler could neither speak nor understand the Turkish of government officials, the Moorish Arabic of the majority of the population nor the Hebrew that the Jews used in their temples. He knew even less of Berber dialects, applying the name of one (Showiah) to all the others. But Shaler did his best to account for Berbers:

Berebers, or Brebers, from which is probably derived the actual denomination of Barbary, which this part of Africa is known by, being probably a corruption of Bereberia, the term in use at this day to designate this country in the Spanish language. But now they are mere classical terms, for these people are unconscious of being either Berebers or Brebers.

Authors who could read Arabic, such as Leo Africanus (c1485-c1554) and Luis del Mármol Carvajal (c1520-1600), had mentioned the presence of Berbers, but Europeans had a hard time figuring out how they related to the Moors. By the 19th century, Moor had become a catchall term, comprising, as Shaler put it: ‘Africans, Berbers, Arabs, emigrants from Spain, Turks, and others.’

He didn’t elaborate on what criteria he used to decide their whiteness, but meant that the Berbers were not Negroes

In spite of all the imprecision, and a good deal of confusion, Europeans were also certain that the Moors were not Berbers. Shaler spoke for the still-reigning conventional wisdom when he wrote: ‘The Berbers … are a white race of men, who inhabit the chain of Mount Atlas, and extend to the borders of the Desert of Sahara.’ The Berbers might live under the political authority of the Moors, Shaler wrote, but ‘the Moorish governments’ have never succeeded in subjugating them because, politically, the Berbers, ‘like ultra-Mississippian Indians, live in a state of savage independence’. Shaler’s intended audience was Americans, and so his comparisons sometimes took on an American hue. He portrayed the Amazigh, Kabyles, Tuarycks and Siwah – the putative four nations of Berbers – all as white, and so were the Moors and even the Asiatic Arabs. While he didn’t elaborate on what criteria he used to decide their whiteness, Shaler meant that the Berbers were not Negroes.

Writing of Algiers in 1837, seven years into the French occupation, Alexis de Tocqueville expressed the conventional wisdom of the Parisian intelligentsia: ‘We had no clear idea of the different races that inhabit it, their customs, and not a single word of the languages these peoples spoke.’ Yet, he maintained: ‘our nearly complete ignorance did not prevent us from winning, because in battle victory belongs to the stronger and braver, not to the more knowledgeable.’ After taking Algiers, French generals used extraordinary violence to brutalise the natives into submission. Thousands perished in enfumades (‘smoke-outs’), when the French army steered civilians into caves and then started fires to suffocate them. After executing leaders of the Algerian resistance, French soldiers collected their severed skulls and sent them home as trophies and specimens for scientific study. Some are still stored at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris.

The Algerian natives surrendered to the French on the condition that they would be free to practise their religion and to adjudicate conflicts among themselves. Since Ottoman rule had rested on their protection of North African Muslims from Spanish Christians, retaining their status as Muslims seemed primordial to them. Yet, resistance to colonial rule mobilised not just religious but also tribal solidarities. The French needed to find ways to disarm both. In 1844, they established the Arab Bureaus (bureaux arabes), the public face of the military pacification of the natives. Combining brute force, the displacement of thousands of people and the management of their livelihoods, the bureaux arabes subjected Algerians to ‘a constant regime of both euphemised and overt violence … which endured for a century thereafter’, as James McDougall writes in A History of Algeria (2017). In an effort to help administer their new colony, French Orientalists, ethnographers and intelligence officers collected extensive information about the country. But their data were unsystematic and fragmentary. It was not until 1856, when an Irish-born Orientalist published his translation of a 14th-century Arabic history book, that the French figured out how to connect their piecemeal data to a synoptic (and completely new) view of Algerians and North Africans.

‘Abd al-Raḥmān Ibn Khaldūn (1332-1406) was born in Tunis into a family of elite émigrés from Muslim Spain (al-Andalus). His education and upbringing prepared him to serve rulers, which he did all his life. In 1377, he composed the introduction to what became a monumental history of the Maghrib. He called it The Book of Examples (in Arabic, Kitāb al-‘ibar). Ibn Khaldūn’s history focuses on the Arabs and Berbers who founded dynasties, as well as the Turks, Persians and Romans who were their contemporaries. He claimed that history – which he understood as the rise and fall of dynasties – moves from tribal to urban civilisation and back. He believed tribal solidarity was the driving force of history, although he acknowledged that religion could supplement it. While urban civilisation was more complex, Bedouins led simpler lives and possessed qualities that urbanites lacked, such as generosity, courage and honour.

Ibn Khaldūn organised his history into a succession of generations (or strata) of Arabs, Berbers and others. When he lacked historical information about which dynasty ruled at a particular time, especially in remote undocumented periods, he filled the gap with mythological stories and tribal genealogies. Ibn Khaldūn’s history of the Maghrib was thus synonymous with the records of those Arab and Berber tribes who founded powerful dynasties there. For him, just as the history of the Arabs begins in Arabia and extends back into mythological (genealogical) time, that of the Berbers truly begins in the Maghrib. Ibn Khaldūn knew the world as populated from Noah’s offspring. The Berbers must have settled in the Maghrib so long ago, however, that it had been their home basically forever.

In 1844, William Mac Guckin de Slane (1801-78), a native of Belfast educated in Paris, began his work editing and translating Ibn Khaldūn, an author whom French Orientalists had recently discovered. De Slane started by editing the Riḥla, Ibn Khaldūn’s autobiography. Two years later, he became chief interpreter of the French Army of Africa in Algeria, working on editing historical selections from the Book of Examples that pertained to North Africa (Maghrib). De Slane’s translation was published in four volumes as History of the Berbers and the Islamic Dynasties of North Africa (1852-56). It immediately became the Ibn Khaldūn that everyone knew. Even those who had access to the Arabic original now began to read it through de Slane’s translation. Within just a few months, references to the Histoire des Berbères, as it came to be known, mushroomed.

De Slane’s Histoire des Berbères is not, the way all translations are, simply a new text with some relation to the original. It is an enriched version, suffused with modern notions, such as race, nation and tribe – concepts that would have been foreign to Ibn Khaldūn. De Slane’s translation mangled key terms. For instance, Ibn Khaldūn used the complicated and rich notion of jīl to refer to the prominent members of a kin group. Jīl refers to something like a generation, members of a group who lived at a particular time, and, by extension, the group itself. When de Slane thought that Ibn Khaldūn did not mean ‘generation’, he translated jīl as race. But because for Ibn Khaldūn kinship groups are related to civilisation or type of social organisation, de Slane found himself referring to nomad and urbanite races. In addition to jīl, he translated terms such as umma – which described ‘nations’ or ‘people’ such as the Arabs and Berbers but also subgroups that belonged to them – as ‘race’. Thus in de Slane’s translation, the Berbers became a race, but so too were the Kutāma and Ṣanhāja. Likewise, the Banū Hilāl and Banū Sulaym tribes belonged to the fourth race (ṭabaqa) of the Arabs.

Race was very much on de Slane’s mind. Amazingly, he often just inserted ‘race’ even when there was no Arabic term to translate. Ibn Khaldūn’s kings of Zanāta (mulūk zanāta) became de Slane’s ‘kings of the Zanātian race’. In a different passage, the Senegal River separated the Berber race and the black race. De Slane so completely misrepresented Ibn Khaldūn’s ideas that they are, in his translation, impossible to recover. Where Ibn Khaldūn saw genealogies filling the gap of knowledge about particular dynasties, de Slane turned again to races.

De Slane’s notion of race helped generals, ethnographers and doctors avoid having to think about Algeria and its history

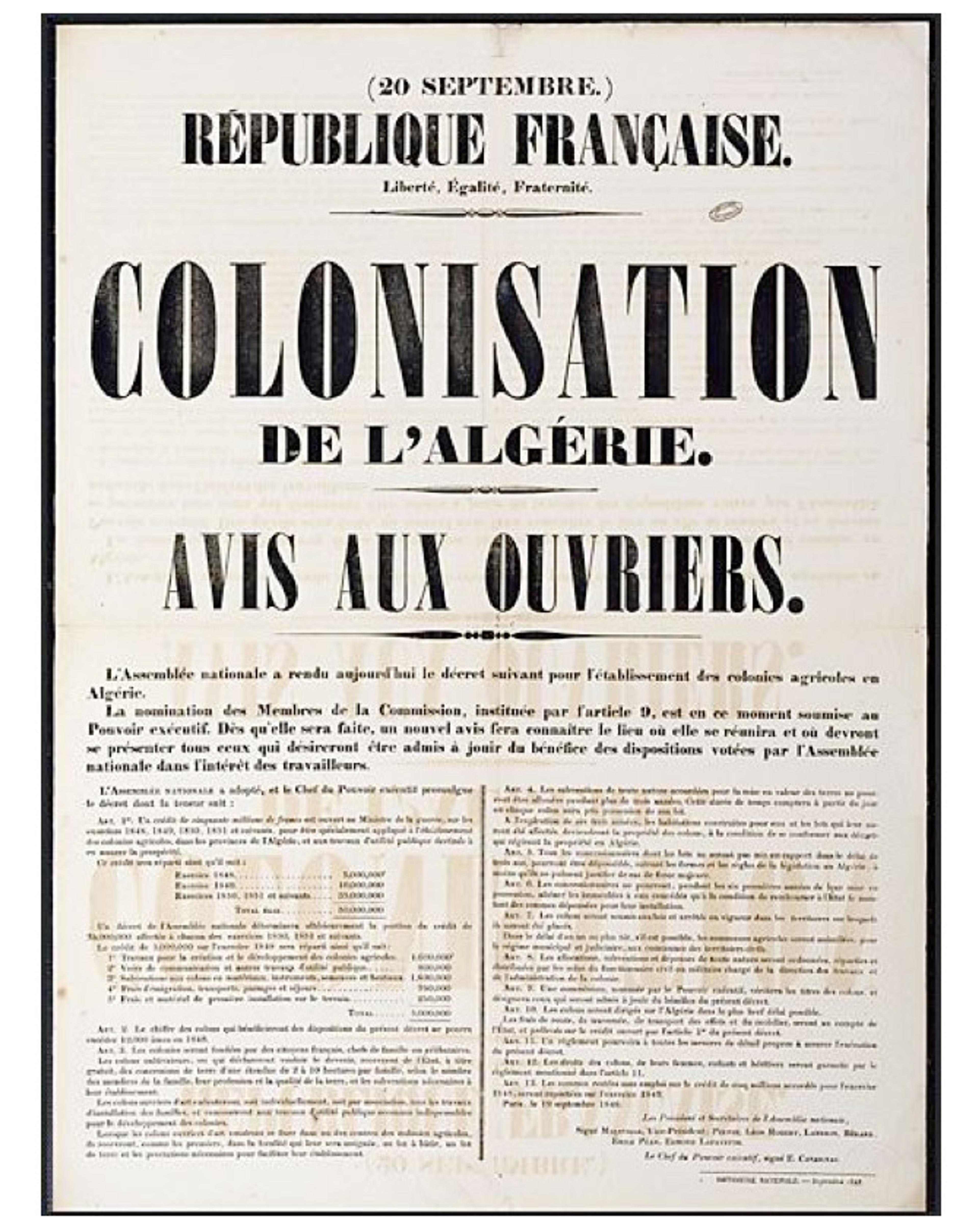

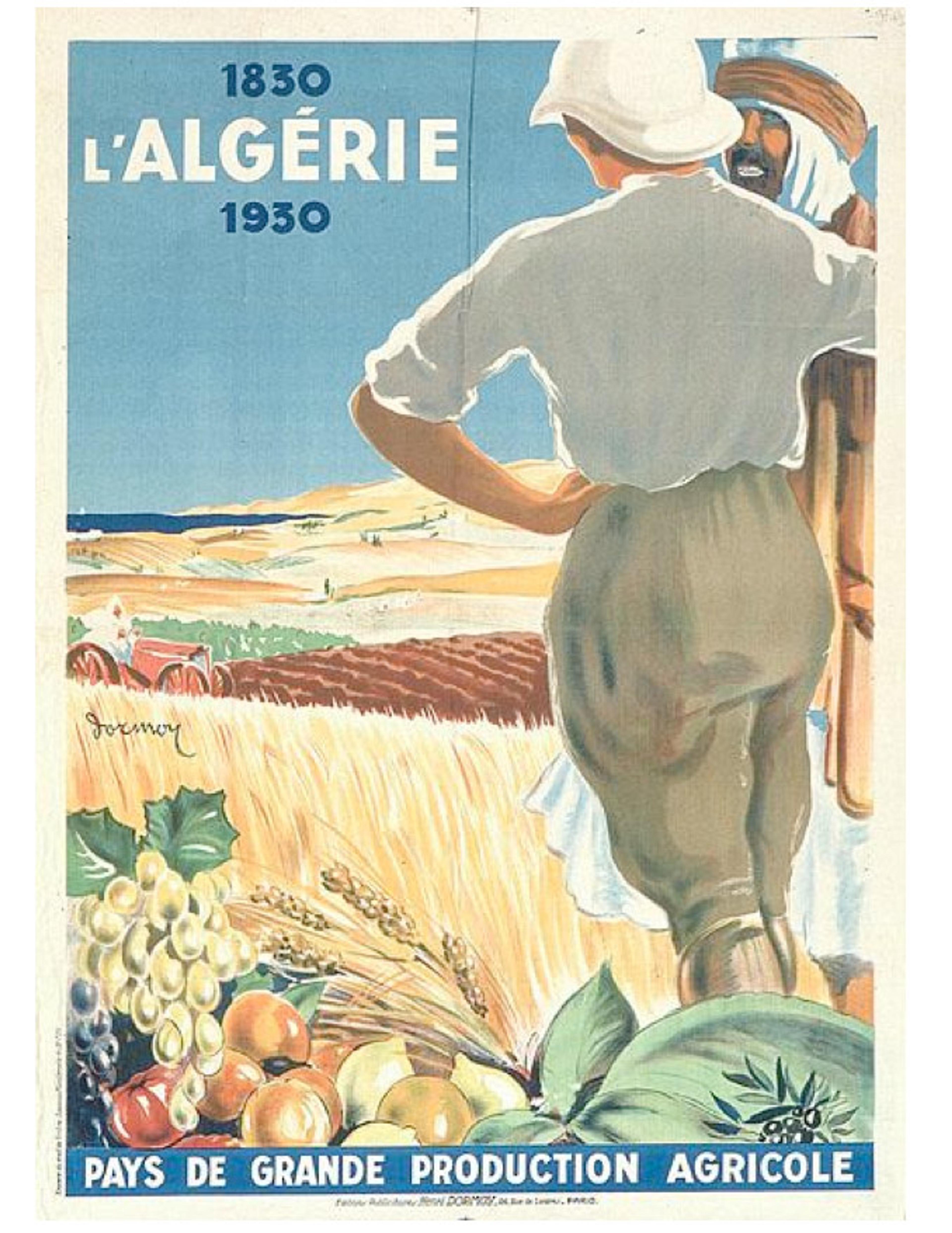

In 1839, the French government had begun to use the name ‘Algeria’ for all the former Barbary states under its control. In 1848, after defeating the uprising led by ‘Abd al-Qādir (1808-83), it annexed that Algeria, creating three new French provinces (départements) of Oran (west), Algiers (centre) and Constantine (east). French Algeria continued to expand, although the conquest of the Sahara took until 1905. Together with their military takeover, the generals oversaw a transfer of property on an epic scale. From urban real estate to agricultural land and natural resources, the wave of expropriations redistributed an entire system of wealth and set the foundations for a new colonial society.

De Slane’s liberal use of the notion of race helped generals, ethnographers and doctors avoid having to think about more subtle and complex details of Algeria and its history. For this favour, they made Ibn Khaldūn the most authoritative source on the natives; Ibn Khaldūn, mistranslated by de Slane, became the patron saint of experts. In 1870, the French organising a new system of colonial rule turned to the church of Ibn Khaldūn and its ancient truths about the indigènes, as the new colonial laws called them.

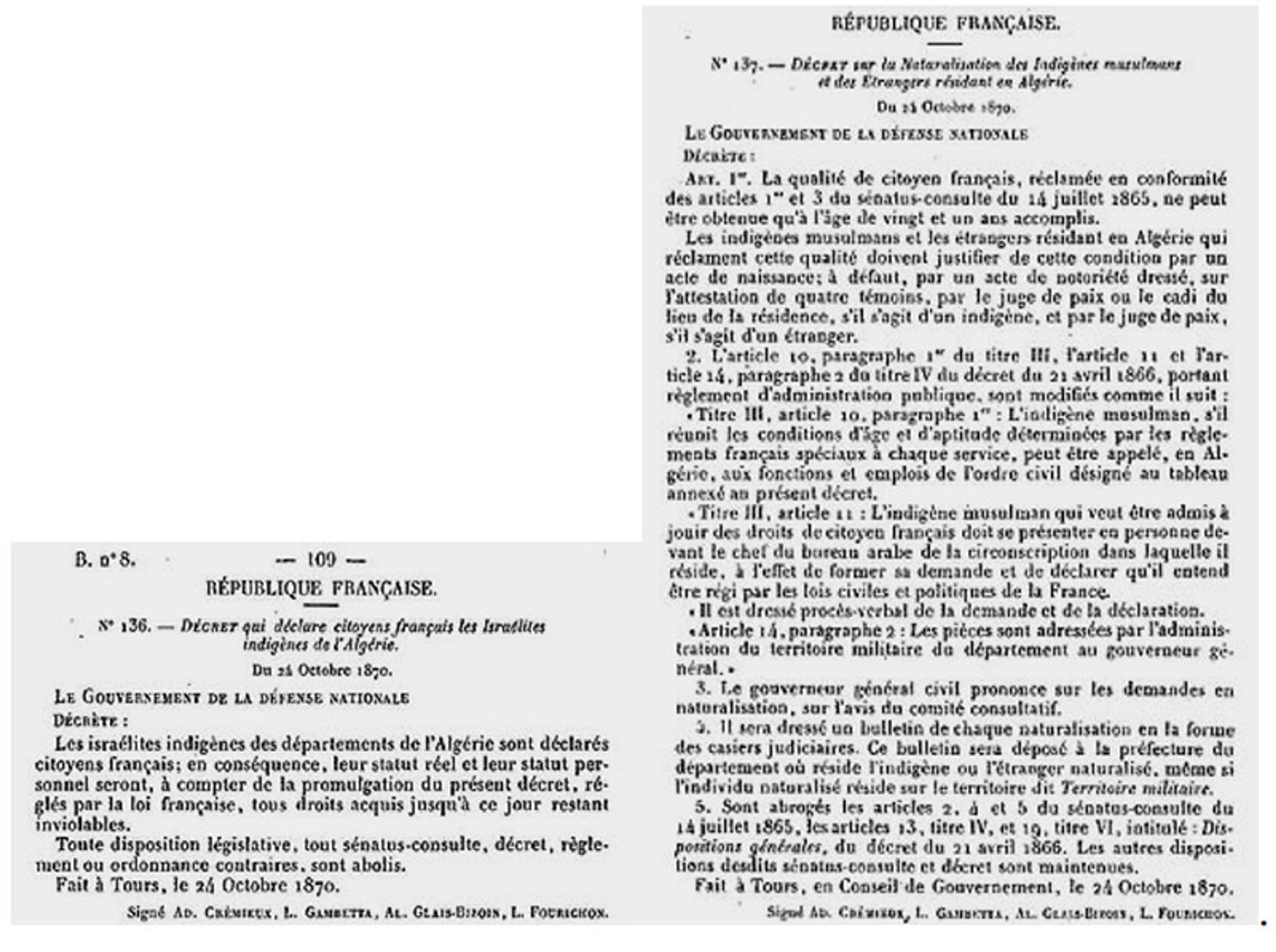

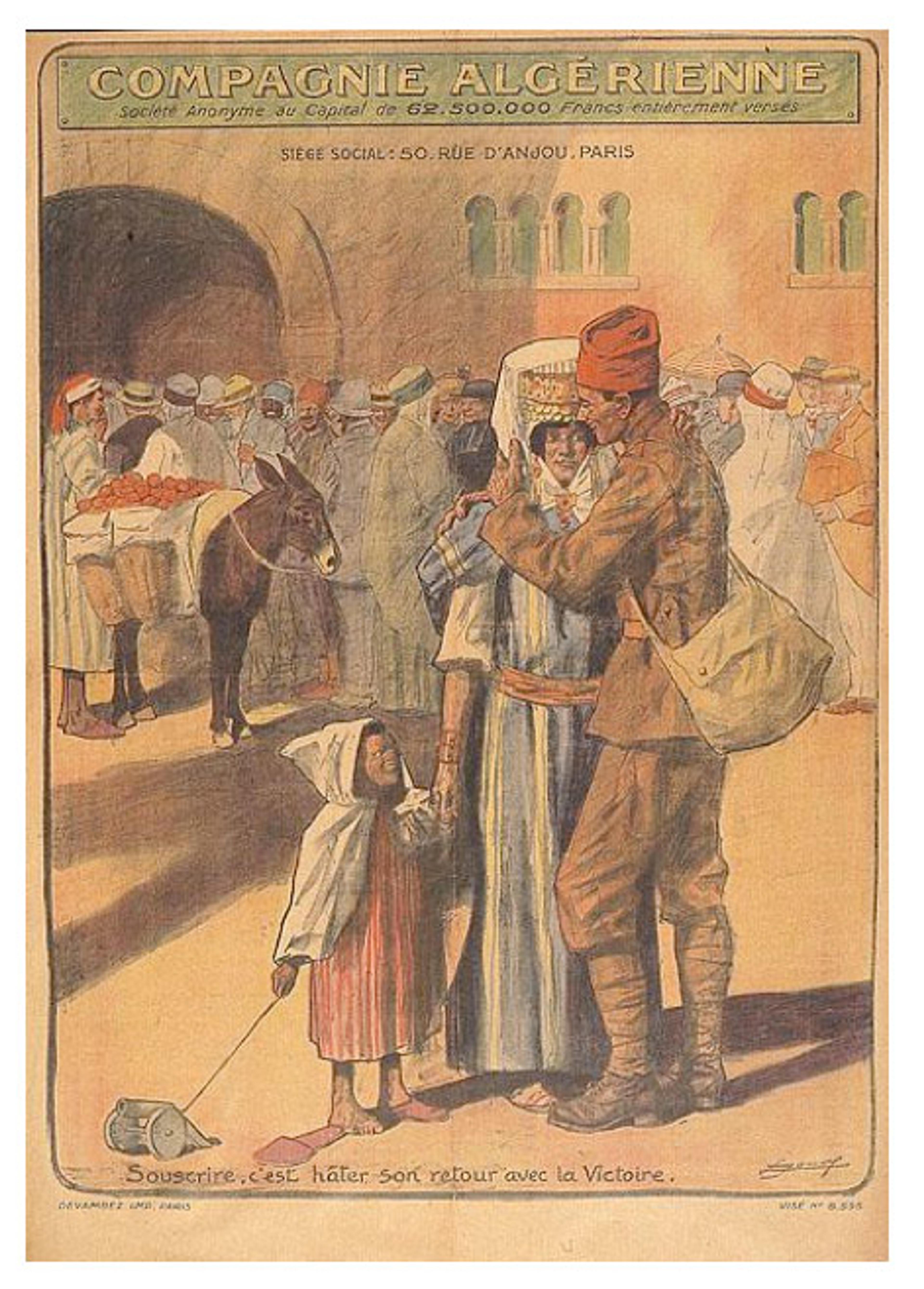

Courtesy Archives Nationales

French colonialism in Algeria aimed to avoid the mistakes made in the Americas that led to France’s losses there. It would have a clearer vision and be better organised. The correct approach was hotly debated by the French, but in the end settler colonialism won the day. In 1870, the minister of justice Isaac-Jacob Adolphe Crémieux (1796-1880) introduced a law that would set the architecture of the colonial system in Algeria. As president of the Alliance israélite universelle, Crémieux convinced the French political class to confer French citizenship on Algeria’s approximately 35,000 Jews. For Muslims, on the other hand, the so-called Crémieux Decree required that each Muslim must apply as an individual for citizenship and formally renounce Islam and its law. Muslims would be second-class indigènes in French Algeria, subjects without full political rights.

The so-called Crémieux Decree. Courtesy Wikimedia

So it was Islam, not race, that served as the basis for the official disenfranchisement of the indigènes. Again, however, de Slane’s version of Ibn Khaldūn is important. By representing so many things as racial, and time and again inserting race as a key component of Algeria and its history, de Slane’s translation helped the French to racialise Algerian Muslims into two different peoples: Arabs and Berbers. The division reduced the threat of their partnership against the settlers. Although they might not have understood the fine points of Islamic theology or jurisprudence, the colonists knew that the new racialised Islam benefited them. France’s settler colonists were entitled to receive expropriated land at very favourable financial terms. They also enjoyed a legalised system of protections from the natives. Eventually, French colonisation led not only to the pauperisation of the natives, but also to the emergence of a few very large estates and a large number of poor farmers who depended on the colonial state for their economic survival.

Courtesy Archives Nationales

The gradual industrialisation of Algeria made many of these poor European farmers into an urban working class with better jobs and pay than the Muslim masses. As the mass poverty of the natives became a conspicuous social fact, it served as evidence of all sorts of ideas about their own responsibility for their condition. Again, the French turned to de Slane’s translation of Ibn Khaldūn for authority: the Arabs (ie, medieval Bedouins) know only how to destroy civilisation; the Arabs were one race, the Berbers another; the Berbers’ conversion to Islam was superficial; under Islam, the Arabs victimised the Berbers; the Berbers were originally white, the (Semite) Arabs were not.

French missionaries used Ibn Khaldūn to remind the Berbers of their purported Christianity before the Arabs: after all, St Augustine was Berber. Ibn Khaldūn’s focus on civilisation allowed colonial intellectuals to cast the mission of the colonial state as one in which France would help natives shed those attributes (Islam) that retarded their emancipation – although the education of natives never became a budgetary priority. To the French, the landless and poor Berbers were responsible for their own hardships because they stubbornly clung to the Islam of the Arabs who victimised them (more than 1,000 years ago).

The French have held no monopoly on self-serving mistranslations of Ibn Khaldūn. In 1958, an English translation of The Muqaddimah appeared by Franz Rosenthal, an Arabic scholar at Yale University. Rosenthal’s translation continues in the spirit of de Slane, offering to Anglophone readers an Ibn Khaldūn saying things about race that he never thought, and a North Africa full of Arab, Berber and black races. Since command of Arabic has, amazingly, never been de rigueur for Westerners claiming expertise on North Africa, it is de Slane and Rosenthal’s translations that have formed the views of countless French and American diplomats, policy experts, journalists and even academics.

Courtesy Archives Nationales