There is only one true sexbot that you can go out and buy today. Her name is Roxxxy, and she is a ‘robot companion’ intended to look human, or something very close. She’s 5’7” and slender. She’s got a wide range of hair and eye colours. And depending on the model you choose, she can ‘hear’ you, ‘talk’ to you, and ‘feel’ you.

First introduced in 2010 after nearly a decade of development, the Roxxxy line now includes RoxxxyGold, RoxxxySilver, and RoxxxyPillow, as well as Rocky. Only RoxxxyGold comes equipped with a ‘personality,’ although RoxxxySilver will talk during sex. RoxxxyPillow, the least expensive model, is only the torso, head, and three ‘inputs’ – vagina, anus, and mouth. Unlike the other models, which are full-sized, RoxxxyPillow can be tucked away discreetly when not in use.

Roxxxy is decidedly a robot. Unlike some of the gynoids and actroids, Roxxxy does not quite produce the ‘uncanny valley’ effect, where a robot is so close to being human but different enough to create a feeling of revulsion. Roxxxy is mannequin-like, and comes with her very own personality. While she likes the same things as her owner, she has moods too, and can sometimes get sleepy. She can also take on additional preprogrammed characteristics, such as ‘Mature Martha’, ‘Young Yoko’ or ‘Frigid Farrah’. Young Yoko is aged just over 18, but she’s inexperienced and wants to learn, whereas Mature Martha can show her owner the ropes. Wild Wendy is up for anything, while Frigid Farrah needs a lot of coaxing.

What are these interactions like, in practice? Stilted, to be sure, but also surprisingly detailed. Take Mature Martha, for example. She talks to you in an empty robotic voice that sounds a little like a mix between Siri and MacinTalk Victoria. She has the base personality – a mature woman who’s got a lot of professional experience and “erotic experience.” But she’ll talk to you about your specific interests, too. If you’re into golf, she’s into golf. Love Maseratis? Nothing turns her on more. Martha’s purpose, just like Young Yoko or S&M Susan or Wild Wendy or Frigid Farrah’s purpose, is to provide more than just sex. She’s there as a True Companion, to talk to you before and after sex, or maybe in place of it if you’re not in the mood. She’s there waiting for you to connect with her.

The personalities offered by Roxxxy are crude types, but they are instructive, insofar as they tell us what sexbots are likely to proliferate, especially as the technology to customise them becomes more sophisticated. In a few decades time, sexbots might be as commonplace as vibrators. We’d do well to start thinking about what they might mean for human culture.

Where did the sexbot come from? Humans have been using sex toys of various sorts for tens of thousands of years. The oldest known dildo is more than 20,000 years old, dating back to the Upper Paleolithic era. Unlike Roxxxy, it is made of siltstone. Dildos, vibrators, penis rings, anal beads: these have been with us, and in us, for a good long time. Computer-driven sex toys and teledildonics – those that combine telepresence and sex – date back to the mid 1970s, but they serve the same purpose as previous sex tech. They provide intimate pleasure and exploration, sexual stimulation, and in some cases, a window into one’s identity.

Before they were called ‘sex toys’, doctors used vibrators as medical devices. Midwives and occasionally physicians treated female illnesses such as hysteria through a type of masturbation referred to euphemistically as ‘pelvic massage’. For centuries, they performed this massage by manual stimulation. The first vibrator was introduced in France in 1734 but it was not until the late 1800s, with the steam-powered and electromechanical vibrators, that doctors had any mechanical alternative to using their hands. As difficult and cumbersome as the steam-powered machine was to use, many doctors were grateful for it just the same, given the effort manual stimulation required.

In 1902, Hamilton Beach Brands filed a patent that enabled them to sell vibrators directly to consumers, rather than only as a medical device. With this patent, the vibrator became the fifth electrified domestic appliance, beaten only by the sewing machine, the fan, the tea kettle, and the toaster. The vibrator was still advertised as a health and medical device but, in the 1920s, the sexual use of vibrators became more explicit through pornography.

In subsequent decades, vibrators tended toward two main shapes: sleek insertable dildo-style vibrators and external wand massagers. The wand massager, made famous by the Hitachi Magic Wand, was widely marketed as a health device for ‘gentle massage within the home’, with the nudge-nudge, wink-wink of its most popular use as the Cadillac of vibrators simply implied. Demand for a sex toy that provided clitoral stimulation — without which most women cannot orgasm — led to the creation of the Rabbit vibrator in the 1990s, a style that features both an insertable phallus shape and an external attachment with two vibrating rabbit ears.

Some even have sensors built into their breasts and genitals, in order to respond sexually, but they are not built for sex specifically. At least not yet

There is now a wide variety of vibrators and sex toys available for women and for men. Beyond the traditional shapes and types, remote-controlled vibrators, multispeed and customisable vibrators, and the Rabbit’s Ina model: a smooth and contoured dual-stimulation vibrator that no longer has playful animal shapes but instead looks vaguely sculptural. Then there are smart toys and machines such as the Bluetooth WorldVibe vibrator, with shareable vibration patterns and an app that controls the device, and the Limon, which uses ‘squeeze technology’ that allows one partner to squeeze the toy, programming it to a personalised rhythm and pressure the other can enjoy. There’s also Vibease, the ‘world’s first wearable smart vibrator’, which is controlled by an app on either iPhone or Android. One partner can wear the vibrator inside her underwear and the other, regardless of where she or he is, can control it.

There are toys for men too, although unlike toys for women, which straddle solo and partner play, heterosexual men’s toys are largely masturbatory devices. There is the Fleshlight, a sleeve of ‘flesh-like’ material housed inside a fake plastic flashlight. Remove the cap and the top of the material is shaped like a vagina, an anus, or a mouth, ready to be lubricated and penetrated. Or there’s the Soloflesh Personal Satisfaction Device, a sex toy shaped like a floating pair of buttocks with a vagina; just fill it with warm water and it’s ready for sex.

From there, things shade into something more sexbot-like, such as FriXion, which uses sensors and robotic accessories to assist in remote-controlled sex. The robot appendages use haptic technology, which allows users to grip or penetrate their partners across long distances, with touch not words. There are also chatbots that can emulate human conversation, by responding to your cues: they’ll ask if you’re into big tits, and tell you: ‘I’m feeling a little naughty ;)’.

But apart from Roxxxy, there are almost no examples of actual sexbots in existence. There are human-like robots, particularly the actroids from Japan, of which Project Aiko is perhaps the best-known example. These robots have been created to be the ideal girlfriend or the perfect secretary, and they do speak and respond to human touch. Some even have sensors built into their breasts and genitals in order to respond sexually, but they are not built for sex specifically. At least, not yet.

‘Right now, we’re at an inflection point on the meaning of sexbot,’ says Kyle Machulis, the California-based world expert on sex technology. ‘Tracing the history of the term will lead you to a fork: robots for sex (idealised version: Jude Law in the movie AI), and people that fetishise being robots (clockworks, etc). There was a crossover of these in the days of alt.sex.fetish.robots, but I see less and less people fetishising the media/aesthetics, and more talking about actually having sex with robots.’

Some of the newest and most intriguing sex technology veers away from traditional sex toys in a particular way: it is based around sharing and connecting. A vibrator is an individual’s device that can be shared, but some of the newest forms of sex tech were created with the express intent of sharing. By and large, teledildonics and sexbots are made for and marketed either to couples or to men. Almost none are marketed directly to women, which means that the way we create and view sex technology is being filtered through a very particular perspective: a heterosexual male one.

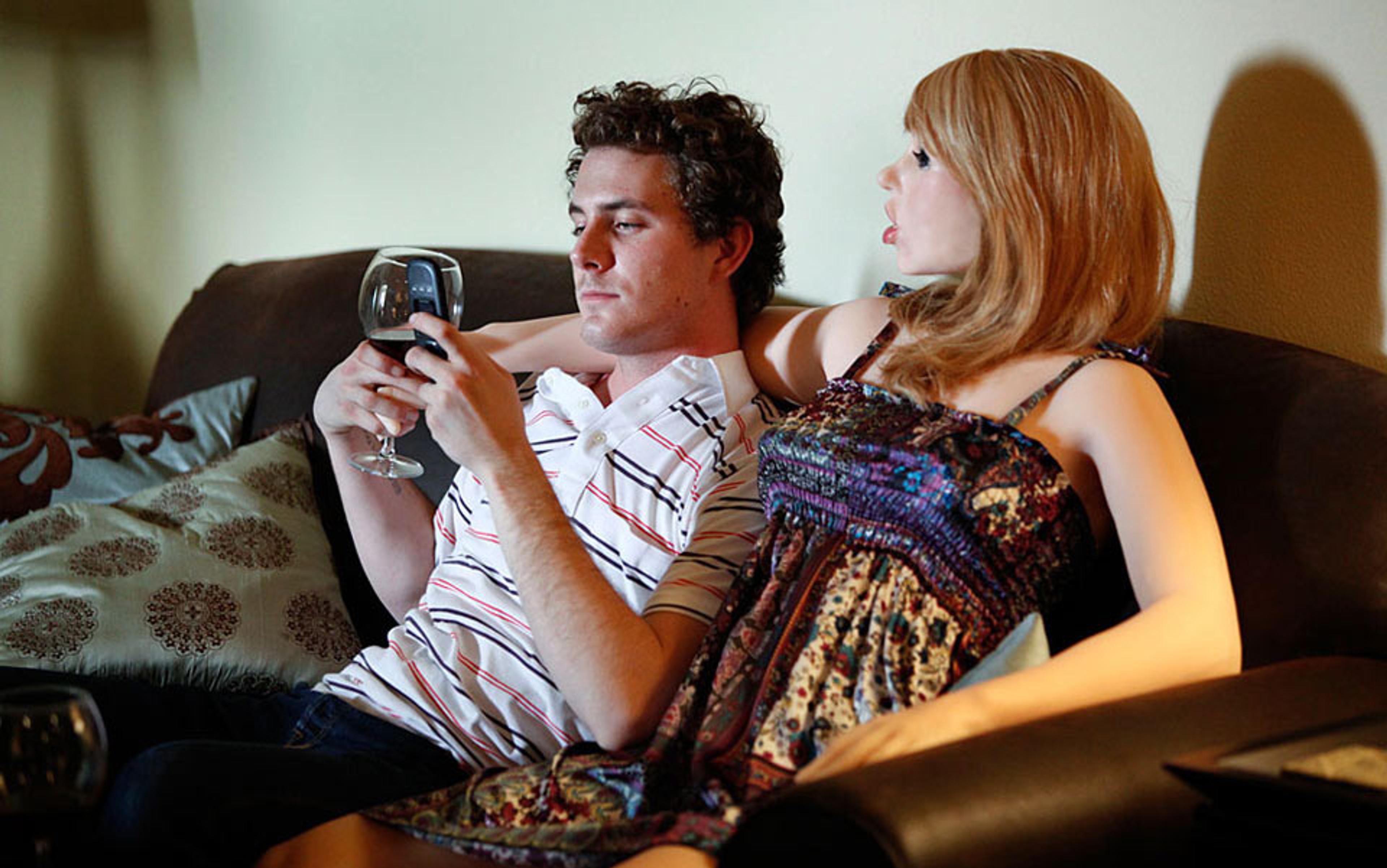

Much of the discourse around emerging sex tech is male-focused. Roxxxy’s roots were in the recreation of a friend lost in the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, but she has grown into a sexbot who exists to match and please her owner. Some find this servitude unobjectionable, because AI is still very much not human. But what if we think about sex technology and sexbots as part of a shared experience? What if we work to program these sexbots so that they are not simply objects to control and swap like livestock, but beings with whom to share intimacy? Sex toys have had to emerge from the shadows of female hysteria, sexual dysfunction, and shame. Should sexbots be created with the seeds of their own stigma built in?

we are programming them to be like a specific type of person: the type of woman who can be owned by a man

Perhaps the best-known work on intimate relationships with robots is by the British author, chessmaster, and CEO of Intelligent Toys Ltd, David Levy. Most of the discussion regarding the ethics of robot sex centres on his article ‘The Ethics of Robot Prostitutes’ from Robot Ethics (2011), wherein he separates types of sexbots according to their sophistication. Levy argues that as long as sexbots are artefacts, without ‘artificial consciousness’, there are no ethical implications in having sex with them or using them for prostitution. However, should sexbots attain artificial consciousness, Levy argues there may be both legal and ethical implications not only for humans but for the robots themselves. But even if sexbots are not currently conscious, they do have the external markings of personhood, and we are programming them to be person-like. Indeed, we are programming them to be like a specific type of person: the type of woman who can be owned by a heterosexual man.

If women are the model on which most sexbots are based, we run the risk of recreating essentialised gender roles, especially around sex. And that would be too bad, because sex technology has the potential to alleviate longstanding human problems, for both men and women. Sex tech can help us take on sexual dysfunction and profound loneliness, but if we simply create a new variety of second-class citizen, a sexual creature to be owned, we risk alienating ourselves from each other all over again.