Last winter, I moved to Lebanon from Turkey. Before that I was in Saudi Arabia. The Middle East, with all its chaos and calamity, was a fascinating place to be, but it also required a lot of effort to make something like a normal life. Moving to Beirut, a city that some still compared to Paris, I thought things might quieten down at last.

The city proved me wrong. There was a shoot-out on my street. My journalist friends were losing their minds trying to cover Syria. Colleagues were getting killed. Hoping to find something other than liquor and worry to take my mind off things, I found myself entering a room with mirrored walls. The space was hushed, with soft light from recessed bulbs. Hesitating, I tiptoed to a spot by the wall, unsure — unsure of what? Of everything, really. Then I took off my shoes, laid out my watch, and took a deep breath.

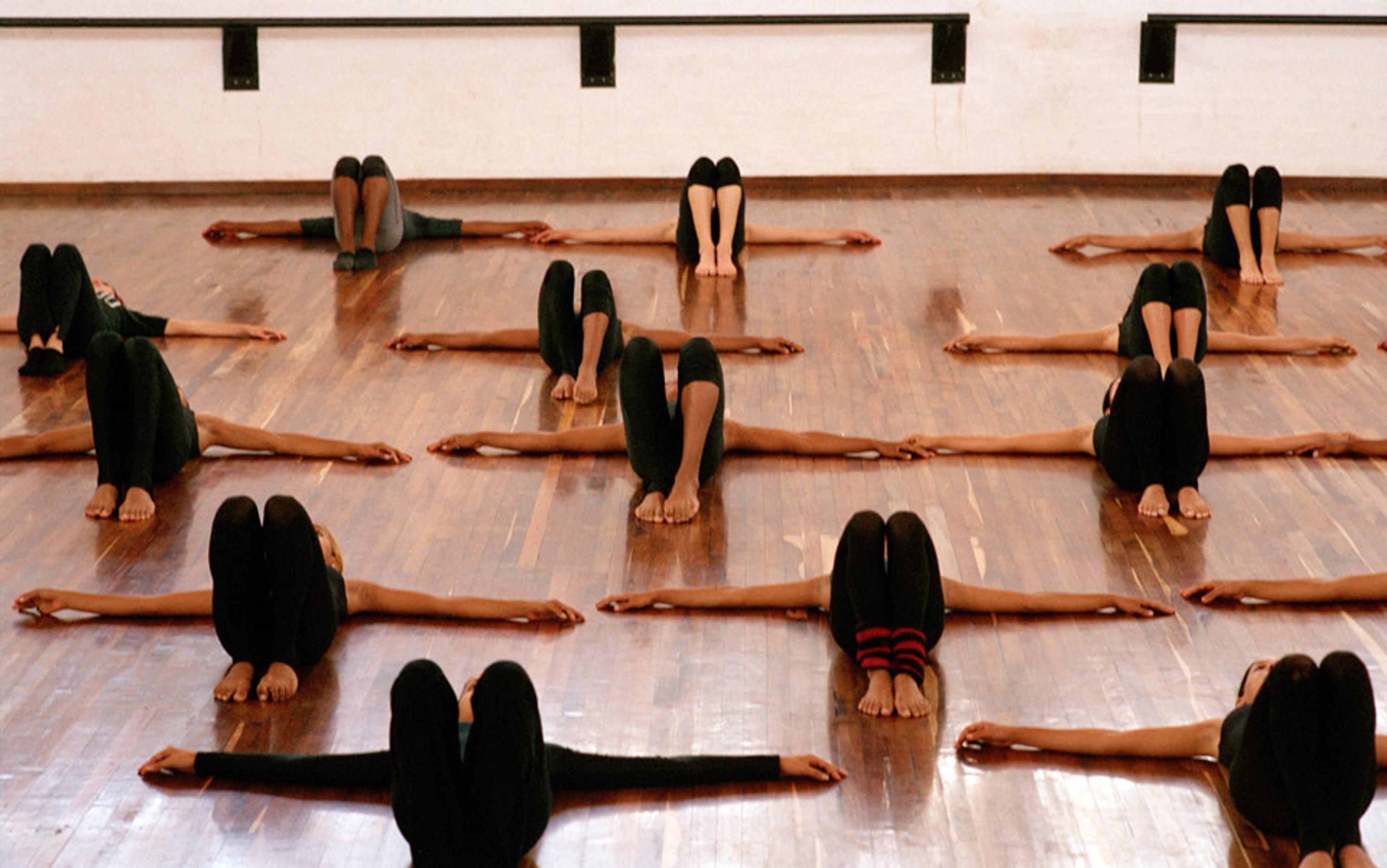

On green mats all around me, creatures writhed in tight clothing. I stood still and tried to look as if I belonged here, to breathe as if I thought this might work. Inside, I was thinking we were all doomed, that our hearts were impure, and we cared about the wrong things, and it couldn’t be helped, and nothing could be done. My heart was beating too hard and I was sweating already. Nothing good could come from any of this. Do you stand on the mat? Or sit on it? I wasn’t sure how to engage with the mat.

Yoga. It sounded so … ethereal. And these didn’t feel like ethereal times, here in Beirut, where my wife was a correspondent for American radio. They didn’t feel like ethereal times anywhere, really. An ugly election was playing out back home in the US, a war kept bursting in from next door, and there was a general absence of anything to feel proud of or comfortable with or confident about. Yet yoga could set you free. I heard that no matter where you were, if you tried hard enough, yoga could make you buff and calm and happy and untroubled. These were things I desired, things we maybe all deserved.

I sought a friendly face, but the women — it was all women — seemed shut off to the world, and each was in the middle of doing something bendy. There was a slow flurry of limbs, all these special poses, each of which seemed to say: I am at rest, I am lithe, and the world is ready to let me do this. I wasn’t so sure the world was ready to let us do this. More to the point, I was surrounded by nearly naked ladies, none of whom even met my eyes. We spoke no words. Maybe I should just relax. The woman beside me bent over, a strange salute from her hindquarters, almost like, Hey, friend, is this so hard? Why the sad face? Be here, with us, doing this, now.

In walked the instructor, Tania. She had olive skin and severe eyebrows, and seemed nearly seven feet tall. An impressive layering of scarves and sweaters hung about her, as if she’d just descended from some inclement mountain. I sat down and hugged my knees, fearful and grateful at once. It might hurt, but at least there was someone to tell me what to do.

Tania took a spot on a special mat and sat in the lotus position. The room filled with the warm sounds of world music, underscored, it seemed to me, with the sharp rat-ta-tat of gunfire. I was hearing things. My heart ran like a baby gazelle in my broad, manly chest. But I am lying. I do not have a broad, manly chest.

‘You,’ she said, extending a long finger. ‘You have not done this before?’

I hung my head.

‘Just breathe,’ she said.

I realised that I hadn’t been.

Soon enough, my body crunched up into an allegedly restful pose called ‘downward dog’. Tania said it was restful. She said it was called ‘downward dog’. I lifted a leg into the air, holding it well beyond the point anyone would want to hold a leg in the air. I did it because she told me to. Then I lowered that leg and lifted the other. Soon I was lifting a leg and an arm. This did not seem tenable. Presently, Tania encouraged us to ‘hop, if you can, or walk’ our way to something called a plank. I wanted to smack, if I could, or perhaps thwack, whoever invented this, but Tania led and I followed, and by God I started to get into it.

All of a sudden I had my legs up over my head, supporting myself with bent arms, doing a shoulder stand.

‘You must be careful,’ said Tania, running over. She eased me back to the ground. ‘You’re not ready for this yet.’

In a haze, in Tania’s capable hands, I thought about how easily people were getting hurt. Syria was a war zone. In my daily life, I consorted with a handful of the people, including my wife, who were tasked not only with not dying but also with making sense of what was going on. And yet someone among us had to remember to buy milk. Then there was also drinking: we had all become quite good at that.

So often self-improvement was self-directed, a walk down a strange path. How comforting, in a world of unknowns, to have signed up for a guided tour

I knew I needed a change. With yoga, there was a plan, a beginning and an end. Even hung-over I could follow along and not screw up too badly. With Tania’s instruction, I felt previously unknown muscles twitch in my thighs, abdomen, biceps, calves, lower back. My toes and even my arches seemed to buzz. It was harder than anything I’d ever done before. Yet there wasn’t much risk of failure. So often self-improvement was self-directed, a walk down a strange path. How comforting, in a world of unknowns, to have signed up for a guided tour.

For the last 10 minutes we lay in silence. Tania crept beside me, hands again on my arm — there was even form for lying with your eyes closed — and then she pulled down the collar of my shirt and rubbed some kind of scented oil into my neck and ears.

Over week and months, I wouldn’t exactly stop drinking or come to terms with our ostensibly perilous life in Beirut. I wouldn’t, in the end, figure out what to do with myself. But with yoga, I was growing stronger. The pain in my muscles gave way to tightness, an ability to balance, a steady breath. Oh, sure, I could still sense darkness gnawing at the edges. Nevertheless, every day, for nearly two hours, I could enter a room where everything was right, a small place bathed in light. I’d put my faith in Tania. In her hands, I knew what to do. And so, for at least some of the day, there were no gnawing questions, just a series of softly spoken answers.

Then, one day, Tania said she was leaving. Telling the assembled class, of which I’d become a fully fledged regular, she hung her head. I wanted to scream ‘Straighten your back, Tania! Strong spine!’ Panic rose up: was she really leaving? Who would teach this class? There were whispers about a daughter in trouble, a flight to America, a New York yoga studio, a new job. It had never occurred to me that she might have a life of her own, her own questions, her own darkness. One last time, we all closed our eyes, even Tania. I tried to imagine a new teacher, different hands.

A few days later, trying out an instructor I’ll call Greta, I tried not to be unsettled by the unfamiliar woman sitting in Tania’s spot. She began to play music, but it was loud. Her movements were hurried and preening, and she tossed her gorgeous hair a lot. She seemed interested in her own body and its smooth moves, but not so much in how her students were doing. Covered in sweat, feeling lost, I walked out, thinking I might never return.

I left Beirut soon after that, for a summer in America. Staying with family I slept well for the first time in ages. After several months of home cooking, I also gained 20 pounds. Returning to Beirut in the fall, my plan was to cut down on the booze, eat right, and return to the gym. First off, I grabbed a mat and a spot in the old room. But without Tania, without the imminent danger of going over the edge, I found myself unable to sit still, no love any more for the feeling of being told what to do.

I could have tried other classes, but I couldn’t bring myself to find and maybe lose yet another teacher, so I began to pursue solitary activities. I started swimming laps, first for half an hour, then an hour. I couldn’t always strike up the nerve to swim, so on alternating days I started climbing a fearsome insectoid structure called an elliptical. Mounting it made me look at least as idiotic as I did when I was bending over backwards and balancing on one leg, and it seemed to offer similar room for error. There was a satisfying little digital readout, too: one time, despite nearly falling off the machine on numerous occasions, the screen said I had burned something like 800 calories. That was an exhilarating achievement, I suppose.

Rarely were my thoughts as dark as a few months before, waiting to hear about the next person who was dead or dying. Syria was still a mess but we’d all gotten used to it, or at least had learnt to cope. Things in Beirut were relatively quiet. So, I made my daily visits to the gym, and I wrote some stories, as did my wife. This was our life.

Then winter descended. There was an increasing influx of refugees from Syria, and all the surrounding countries felt the burn. Turkey fired across the border, and there was a bomb in Beirut that killed three and injured 100. Everyone seemed to be waiting for America or some other Western power to take the lead.

Sensing an old desperation mounting, I redoubled my commitment to the gym, one day even eying the free weights. Maybe I should pump some iron? But with the various illusions of control so fragile, it seemed foolhardy to try anything too difficult, to think about lifting more than I could already carry.