One night, in a tango club in Buenos Aires, a psychoanalyst with an academic face leaned over to me at the bar and said:

‘There are two types of people in tango. Therapists and those in need of healing.’

I already knew we were different types. A year earlier, quite lost inside my life, I had walked into a bar in Auckland and there on the floor was a couple, dancing. They were so erotically tangled in the violin strains of the Ástor Piazzolla tune that was playing, so blissfully at the centre of themselves, that I almost tiptoed out of the bar. But I didn’t leave because I had an instant and devouring desire to be them, one day.

I signed up for classes. I started listening to nothing but tango music – Carlos Gardel, the Argentinean ‘king of tango’, the Paris-based Gotan Project, with their electrotango album La Revancha del Tango; at last, my culturally and personally disjointed life had found its soundtrack. Having washed up in New Zealand as a teenager with my scientist parents after the fall of the Berlin Wall, I was stuck between the Old World and the New. The past haunted me and the future worried me. I was single, scratching a living from writing, and new in town. My posture was terrible and my health a marvel of autoimmune dysfunction. Tango, which sings of all these things and more – drugs, drink, desperation – was a soul balm.

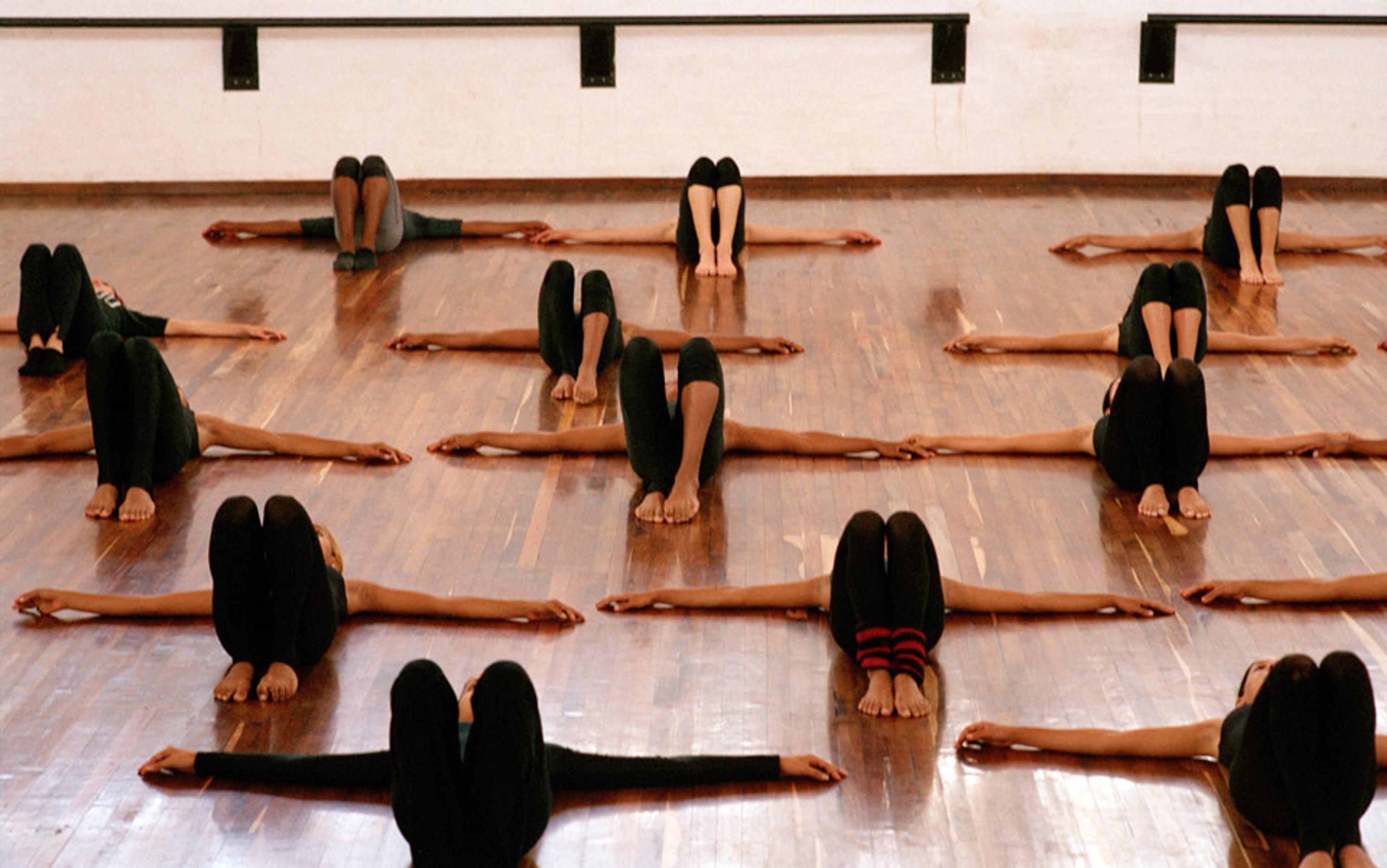

In my flat, I put up posters of a moustachioed Piazzolla with his bandoneón fully open in a gesture of almost sexual possession. I taught myself Spanish, the better to understand the lyrics of moody songs such as ‘I Return to the South’ and ‘The Day That You Would Love Me’ (note the conditional). Five times a week, in steam-windowed city studios, our beginners’ class practised ochos, giros and ganchos, the signature steps of tango.

A flick of fingers on the back, a suggestion of thigh, a syncopation of breath, our dance a private joke, pillow-talk without the pillow

Some, like the giro, or turn, are lyrical: the woman steps around the man in a half-moon crescent that says: ‘You are the apple of my eye’ — an intriguing statement, considering that in 10 minutes she’ll be dancing with another and you might never touch the small of her back again. Other steps are performative, aggressive and gaucho-like, a reminder of tango’s rough-and-ready origins. To ‘gancho’ your partner, you hook your leg through theirs and flick it at the knee in a quick musical heart-beat, while taking care not to sterilise him. Meanwhile, the backward ocho, tango’s emblematic move, has the man advancing half-promise, half-threat, while the woman steps back, drawing a figure eight with her feet, her waist the pinched middle. Then switch — the man retreats, the woman advances with her figure eight, invading his space, saying: ‘Not so fast, honey.’

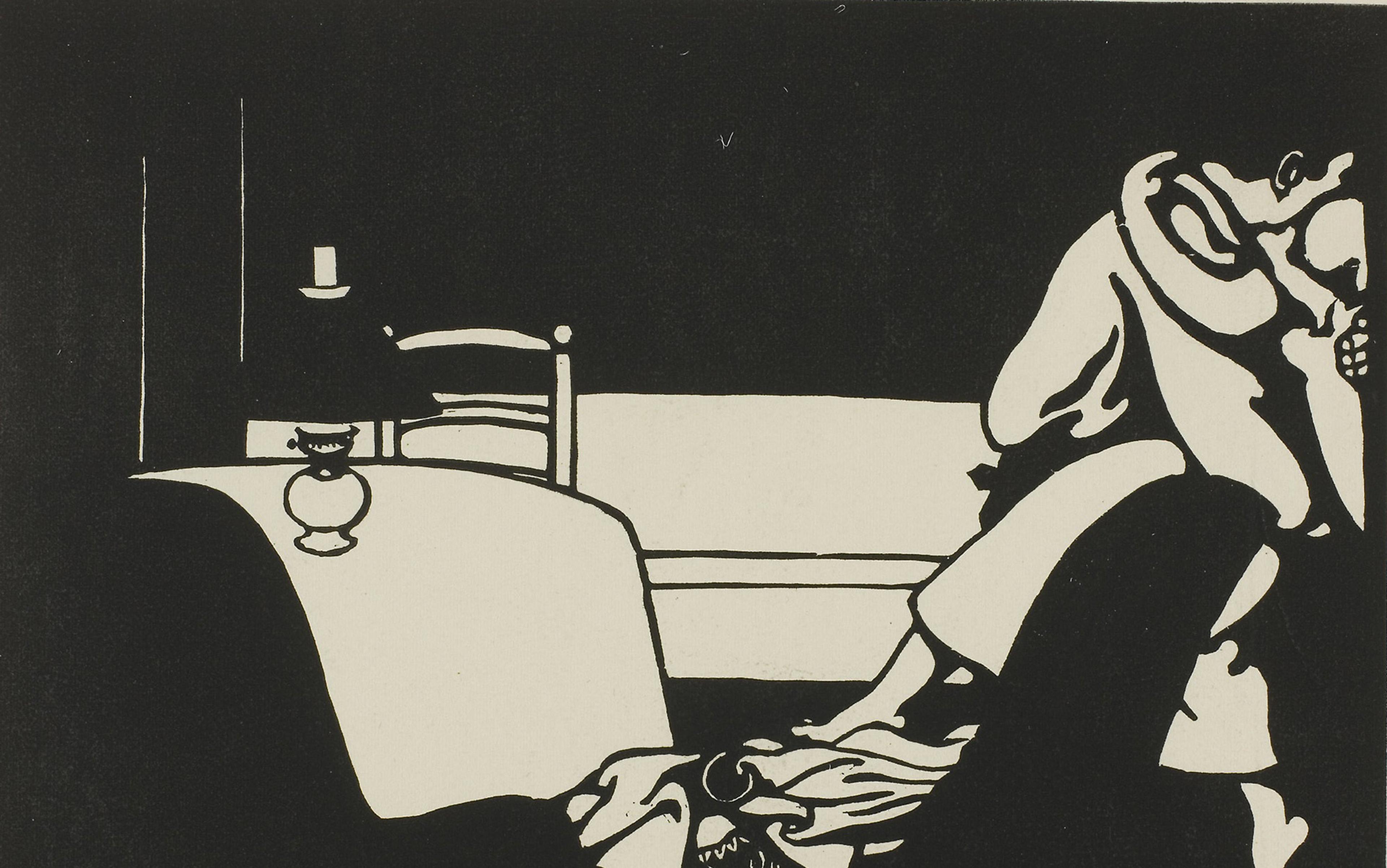

The first tango-dancing women were said to be prostitutes, working-class girls, the non-beau monde of Buenos Aires and Montevideo. Initially, they danced in the twilight slum streets, home to immigrants, wide boys, the dispossessed of the Pampas, and girls with nothing to lose. Until one day in the early 1910s, when tango boarded the ships, docked in Marseilles and London, and revolutionised social dancing. Never before had couple dancing been so improvised, so democratic, and so excitingly close up. Goodbye, Viennese waltz. Farewell, snobs. Adios corsets.

I went to Buenos Aires and danced the nights away with strange men of different nationalities, ages, body types and pheromones, and above all — thrillingly different dancing styles. Some were workman-like, fixated on the mechanics of the steps, disconnected narcissists dreaming of the stage. This was autistic tango and it left me feeling used. Others held me in a close embrace and took small steps, as if whispering secrets. Their lead was delicate, a flick of fingers on the back, a change of direction in the chest, a suggestion of thigh, a syncopation of breath, our dance a private joke, pillow-talk without the pillow. This was a revelation: in the tango couple, small is intimate, and intimate is erotic. Small steps. Small gestures, like the discreet incline of the man’s head known as cabeceo and serving as an invitation. You can ignore it or you can meet on the edge of the dance floor, lift your arms, and take the first sideways step, the salida — all without words, because a good dance is already a conversation. This was a magician’s tango and it left me feeling divine.

I was shedding the crippling binary neurosis of Western modernity whereby in matters of body and mind we are either intellecting, or having sex

So there I was, six months later — broke, brainwashed and begging for more. Tango had swallowed me up like a cult. I had acquired the quasi-messianic glow, the dilated eye, the winged step by which you recognise tango addicts and the insane. But what is it, to be plugged into a pool of energy, sensuality, play, and music — if not sanity? And another thing: I was learning to be unafraid of my body and the bodies of others, to shed the crippling binary neurosis of Western modernity whereby in matters of body-mind, we are either intellecting (above the neck) or having sex (below the waist), with a chasm of stifled sensuality in between. I was learning to let go of self-consciousness and fear, to laugh, laugh, not cry — as the happy-sad tango song ‘El Cascabel’ instructs.

Then — did you see this coming? — I fell in love with a fellow dancer. After all, tango looks like the dance of love and it feels like the dance of love. Something is bound to happen sooner or later. We shared the incurable sense of exile that haunts retarded adolescents (we were in our late twenties) and the culturally displaced. We had tanguidad. The cousin of duende, that heightened sense of soul in Spanish flamenco, and saudade, the doomed longing expressed in Portuguese fado, and also distantly related to the German Romantic sentiment of Weltschmerz or world-weariness, tanguidad transcends tango to encompass places, personalities, moments in time, the exquisite pain of the human condition itself.

You see the ruins of the building where you grew up. You sit in a faded port-city alone, at dusk. You grasp that time, and chance, don’t come back. Everything is tainted by memory and yet you are laughing, laughing, not crying. That’s tanguidad.

The relationship didn’t work: between the two of us, we had too much tanguidad, or simply said, we made each other miserable.

The trouble is that tango magnifies. The couple is intensified by the dance and there is no hiding place when your physical, sexual, and temperamental beings are conjoined in the embrace, excited by the minor-key melodies of yesterday, urged by the unrelenting compás of the four beats. One two three four, one two three four, are you following or leading? Why are you leaving, is the music making you sad, or was it me? You’re not playing anymore. I’m not playing anymore. This was a very bad idea.

The good news was, tango had already written all the heartbreak songs I’d ever need. The first song that articulated tango’s metaphysics of urban and erotic alienation was ‘My Sad Night’ (1915), and the title speaks for itself.

This was the first of many lessons that tango had in store for me. The second lesson occurred when I found my tango soulmate, in P. From the first chords, our bodies and spirits fell into unison. Time and worry dropped away. We stepped into a realm of rapture. Here was what life was for. How could reality ever measure up to this? And anyway, who needed shabby old reality when I could have my ecstasy drug administered tangamente, three times a week? The answer that dampened my exaltation was this: P and I had nothing in common, nothing except sublime tango chemistry. I rejected him as a real-life partner, and he rejected me as a dance partner. Self-ejected from our Eden, we each suffered in the arms of others.

Tango is an act of rebellion — against drabness, denial, and death

I was beginning to suspect tango of being a Borgesian maze of psycho-sexual subtext: the couple is everything, and yet the tango couple is either an illusion or a hyperbole. It is never just itself. If you want to leave the couple alone, don’t dance. Tango is the classic romantic film that ends badly and yet we can’t get enough of it: the ultimate Brief Encounter of coupledom. To survive in tango, you must accept this without anger or grief, and that was the third lesson.

The tango embrace represents the couple, it acts out an ideal. This is why the world of social tango is a global subculture, with ‘queer tango’ taking its due place.The promise is there from the first step and, before you know it, you’ve entered the maze.

The paradoxical principle of the tango couple is encoded in their bodies: chests facing, shoulders level, upper bodies the picture of control, while the erotic pursuit of their lower bodies is unmistakable. This dual dynamic is seen in the faces of social and show dancers alike. There is a tango face that you never see in salsa, cha-cha or ballroom: sometimes pained, sometimes pleasured, sometimes both, and always poised on the edge where sex hopes to meet death, or vice versa.

Why do you tango? I asked men and women, and the answers came short and sharp. Because I have secrets, an American woman said. Because every woman tells me a story with her body, a Dutchman said. Because my body is lonely, a Russian woman said. Because I want to die in the arms of a woman, a Frenchman said.

Why do we tango — real-life lovers, dance-floor lovers, ex-lovers, anti-lovers? Because while we are in the arms of another and the music sings of time, and chance passing for us all, we are in the eye of the storm. We cannot die. Tango is an act of rebellion — against drabness, denial, and death. In its embrace, we hope to glimpse in a dusty midnight corner the aleph, the code that will reveal us to ourselves and each other, and therefore heal us. If we’re lucky — as I was, after ten years and thousands of dance-floor couplings and uncouplings — the aleph of tango will manifest itself and we will know something far greater than the ecstasy and agony of the couple: spiritual wholeness, a form of immortality. That is tango’s greatest gift.

Fast-forward years later to that same tango club in Buenos Aires. I was single again, but healthy and happy. A psychotherapist with a smiling face leaned over to me and said: ‘There are no therapists. We are all in dire need of healing. Would you like a dance?’

You bet I did.