It would be an understatement to say that America has an ambivalent relationship with marijuana. The United States is in the world’s top five per-capita consumer of the drug, yet it treats possession more harshly than most of its international peers. The federal government maintains that marijuana has no accepted medical use, but many of the states that comprise the union have entire regulatory apparatuses built around licensed doctors prescribing weed. And despite all the law-enforcement attention, widespread marijuana use has never registered as a public health crisis. There isn’t any evidence that smoking world-class amounts of weed is hurting Americans. But what about not smoking?

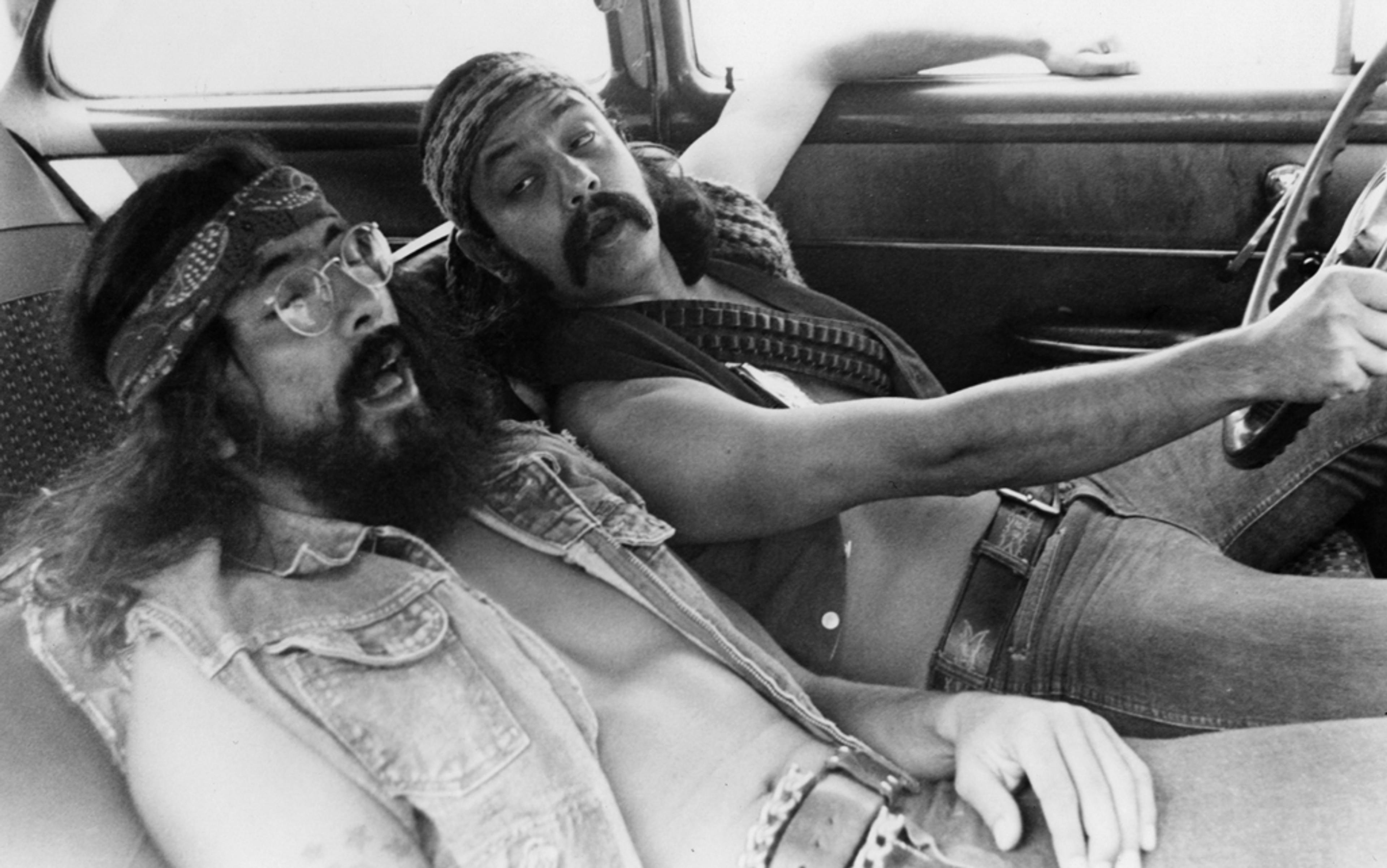

Marijuana withdrawal is a joke, and not a bad one at that. Even though it’s a Schedule I illegal narcotic, scientists can’t agree if marijuana is physically habit-forming. Compared with opiate or cocaine addiction, halting chronic weed use is a piece of cake (if one you might not finish because your appetite is tanking a bit). Marijuana’s hold on you is not harrowing or tragic. As the actor Bob Saget put it in the classic stoner film Half Baked (1998): ‘I used to suck dick for coke… Now that’s an addiction, man. You ever suck some dick for marijuana?’ Addiction science is huge, and it would take a big hole to bury all the lab mice that have overdosed on heroin and prescription drugs. But there isn’t much research on the harms of marijuana withdrawal.

I’ve been what any medical study would classify as a heavy marijuana user for around five years, since I discovered that I was much more invested in my Victorian literature reading when I was high. I went from dragging myself through George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda while repeating: ‘I do not care who gets married’, to turning pages like I was binge-watching on Netflix and thinking: ‘I wonder if they’re going to get married!’ When I wrote an A+ paper stoned, spinning a five-sentence David Foster Wallace story into four pages of analysis between bong hits, I felt like I had passed a test. It didn’t help my work per se, but it didn’t seem to hurt either, and it definitely made the whole thing more pleasurable. Profound insight didn’t descend on me in a puff of smoke, but I did find a new store of patience, a virtue I had always struggled with. I stopped writing sober.

Since then, I’ve been more or less what you could call ‘always stoned’. Through gracious friends, a low turnover rate in drug-dealer cell-phone numbers, and the Transportation Security Administration’s willingness to stick to its delegated priorities (which do not, by the way, include searching for drugs), I was able to go four and a half high-performing years without having to abstain for any longer than a couple days. That was, until last summer when I visited my parents who, though sympathetic enough, couldn’t allow weed in the house for professional reasons. If marijuana withdrawal does exist, I have been through it.

If you use any psychoactive substance every day, you’re bound to miss its effects once you suddenly go without. If your chronic marijuana use makes you hungry, not being able to smoke is going to affect your appetite, but these effects can be hard to see under a microscope. Some studies into user withdrawal symptoms have found decreased hunger, while others use the circuitous language of the scientific method to explain why they didn’t find it when they know they’re supposed to. For instance, a 2003 study by Margaret Hanley and colleagues at the department of psychiatry at Columbia University in New York into the use of the depression and seizure medication divalproex for the attenuation of marijuana withdrawal symptoms, including loss of appetite, concluded that: ‘in the absence of robust withdrawal symptoms, it is not possible to conclude definitively that divalproex does not attenuate symptoms of marijuana withdrawal’. They were searching for the answer to a problem they couldn’t prove existed in the first place, and therefore they couldn’t be sure whether they had found it or not.

When I stopped using over the summer, I did lose my appetite. But was it because I was smoking more appetite-suppressing cigarettes to compensate? Without the controls of a lab setting, I’ll never know for sure. Weed use is full of confounding variables such as this; it’s squirmy and tough to pin down. I did see the return of headaches I suddenly remembered having throughout high school, and irritability to match. My patience vanished, and I was back to the snippy ill-tempered version of myself. Did that make irritability a withdrawal symptom?

There is a significant body of research around marijuana and aggression, but almost all of it addresses the acute effects. In a variety of experiments, participants were required to smoke weed and then undergo quantifiable forms of distress, like tit-for-tat shocking matches or shouting contests. The results are unsurprising: smoking weed makes you chill out (a video of these tests would be extraordinarily popular on YouTube). It wasn’t until 1999 that anyone studied aggression and marijuana withdrawal.

Published in the journal Psychopharmacology, the study ‘Changes in Aggressive Behavior During Withdrawal from Long-Term Marijuana Use’ (1999) by Elena Kouri and colleagues at the Biological Psychiatry Laboratory at McLean Hospital in Massachusetts justifies itself by implying in the introduction that people going through marijuana withdrawal might be committing a lot of crimes. The experiment deprived stoners for a month and put them through a test called the Point Subtraction Aggression Paradigm, which is a simulation in which participants press one button to earn points and another to steal them. The study found that, during the first seven days of withdrawal, subjects had far more stealing responses than the control group, but by the end of the month they had settled down, and their responses matched the control group’s, whose own scores had slightly but steadily increased.

Even if the experimental procedure is a bit inane, this more or less matched my experience. A run-in with unreliable Wi-Fi left me poking the refresh button and snapping at everyone around; if there had been a ‘steal Wi-Fi’ button I could have jammed instead, I would have pushed it straight through the keyboard. But though the results are interesting, it’s easy to see why there aren’t more experiments in the same vein. The study suggested two possible treatments for the aggression problem: the antidepressant nefazodone (which Bristol-Myers Squibb took off the market in 2003 after 20 deaths due to liver failure) and orally administered tetrahydrocannabinol or THC (the main active ingredient in marijuana). A drug with serious side-effects hardly seems justified by the temporary increase in aggressive response the study demonstrated, and solving marijuana dependence with THC pills is like fighting a coffee dependence with caffeine pills. But research needs a reason. Marijuana withdrawal, if it exists, is something to endure, not to solve. And there’s no money in that.

Ex-girlfriends, political struggles, work: all of them blended to a thick black smoothie poured down my mind’s throat

I was expecting the irritability and lack of appetite, but I was not prepared for the dreams. It wasn’t until I was withdrawing that I realised I hadn’t remembered a dream in years. The realisation came in the unfortunate form of intense nightmares. I would wake up more exhausted than when I went to sleep, my mind swimming in pictures and plots. Ex-girlfriends, political struggles, work: all of them blended to a thick black smoothie poured down my mind’s throat. I didn’t repeat the dreams aloud, didn’t write them down; I did my best not to narrativise them at all, to resist crafting plots that might preoccupy my waking hours. Unprepared for the onslaught, I couldn’t tell whether I was simply out of practice or if I really was having extraordinarily strong dreams. Whatever the cause, it took a half-hour every morning just to get my head on again.

I didn’t gain any clarity or inspiration from these dreams. Some people might find swallowing a swamp of subconscious vomit restful, but I am not one of those people. They could have been caused by travel’s effects on my sleep schedule or the mystical powers of a strange pillow, but the dreams seemed physical, too intense to be that psycho on the psychosomatic scale. Withdrawal was real, at least as real as dreams can be.

It’s hard to find firm answers in the body of data on marijuana withdrawal and sleep. For the study ‘Abstinence Symptoms Following Smoked Marijuana in Humans’ (1999), Margaret Hanley and colleagues at the department of psychiatry at Columbia University administered the St Mary’s Hospital Sleep Questionnaire to 12 volunteers going through marijuana withdrawal but found simply ‘no significant changes in response as a function of drug condition’. The divalproex study hooked up participants to sleep monitors to avoid the problems with self-reporting, but still found nothing. Yet studies on rats and rabbits injected with THC showed suppressed REM sleep (the light, early morning sleep), and in some studies human participants self-reported sleep disturbances in withdrawal. The link between marijuana and sleep is strong enough that when the researchers can’t find anything, they seem surprised.

I, on the other hand, definitely found something in my sample size of one. So, like people have done for centuries when they can’t get the right answers from mainstream medicine, I went alternative. To some of my elders, the whole internet might seem like crystal healing, but Google Scholar is as reputable as a textbook. Forums, on the other hand, contain the worst of internet stereotypes: uncited ‘facts’, long personal anecdotes, silly user names, and petty arguments. It’s an amateur medium, but last time I checked there was no such thing as a professional weed smoker. A large body of drug knowledge is concentrated in hyper-personal trip reports: diaries from people’s trips to the edge of consciousness and back. I’d go as far as to say that the best drugs information on the internet is in forums. But you’d better check everything you get on Snopes before you repeat it to your friends.

Even if the best in medical hardware couldn’t prove I was having crazy dreams, the online marijuana community let me know I was not alone. On Marijuana.com, a question about REM from IBoogie00 prompted a seven-page review of the scientific literature interspersed with detailed first-person accounts that matched my own experiences. At the Grasscity.com forum, my exact question had already been asked and answered. The user GolgiApparatus wondered:

ok so ive been smoking weed for 5 years and about 4 and a half years ago I noticed that i stopped dreaming when I slept. especially when I puffed right before bed.

so im taking the first break ive ever had in 5 years its been 3 days so far and these past 2 nights ive literally had 2-3 of the most intense, vivid, and absolutely emotional dreams. its been mentally intense to say the least.

so yeah thats my statement. what do u all think

Scrolling the responses, which mostly ranged from the non-scientific to the pseudo-scientific, satisfied my desire for information more than all the inconclusive and contradictory studies. The working explanation on the forums is that chronic marijuana use suppresses REM sleep where vivid dreams occur, and some users going through withdrawal experience a rebound period in which their brain overcompensates, and the sudden overload of REM sleep manifests in intense dreams. REM rebound is most common after extended periods of sleep deprivation, and it’s also an accepted symptom of alcohol and sleeping-pill withdrawal. But the forum users were trying to explain their lives, not establish normal baselines or test anything under controlled circumstances.

The experience made me ask myself what I was really looking for. We usually assume the problem with doing your own medical research is that you might end up believing the wrong information, but deciding between kinds of truth is more complex than filtering out falsehood. I didn’t want a cure for my withdrawal, and I certainly wouldn’t have taken a pill for it even if the science supported a prescription. Nor did I feel my aggravation deserved sociological study as a criminogenic factor. What I wanted was confirmation that I wasn’t making it up, that I was experiencing a recognised phenomenon.

We don’t name psychological experiences just to cure them; we do it because we need language to think about things

If I could find a reason and a name for what was happening to me, then I could lend some order to my disordered mind. As long as I didn’t know, the disorder seemed limitless and uncorralled, as though it might mutate and overrun its bounds at any time. We don’t name psychological experiences just to cure them; we do it because we need language to think about things, to reflect on what’s happening to us, and bind sensations into concepts. Medical research looks for something different. It looks for things it can prove.

The people who post on forums support each other — to the best of their varied abilities — with information and their own experiences. Instead of relating back to an imagined sober control, these stoners treat abstinence like its own trip. At the Weed Street Journal — which bills itself as ‘the authority in cannabis news and culture’ — an unsigned editorial in May 2011 on ‘weird dreams after you quit smoking marijuana’ suggested this very outlook. After glossing the medical literature, the author’s suggestion was a lot more practical than the conclusion in any peer-reviewed study I saw:

My recommendation for those who stop smoking is to mentally prepare yourself for these dreams and look at them in a positive light. Obviously, some dreams can be terrifying, but more times than not I had some pretty crazy dreams that I really enjoyed. It can actually be a fun part of your quitting process, and I would even go as far as to say you should write down your dreams so you can read the absurdity later.

When I had to take a month off weed, medical research was the wrong place for me to look for answers. Asking people who can inject a bunny full of THC with a straight face to explain my trippy dreams was never a good idea. Sometimes, pothead questions need pothead answers.