Like a lot of people in the autumn of 2012, I watched the TV debates between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney. It was the last big performance in that interminable presidential election campaign in the United States. Every now and then, as Obama did verbal battle with his adversary, I noticed something I didn’t expect to see. It was a gesture he made with his hand: for emphasis, he would point at Romney with his thumb. I wasn’t the only one to have seen this. In a short piece on the BBC website, a reporter wrote:

Featured in the three presidential debates were Romney, Obama, and Obama’s thumb. At the debates, the president frequently jabbed his hand, with his thumb resting atop a loosely curled fist, to emphasise a point. The gesture — which might appear unnatural in normal communication — was probably coached into Obama to make him appear more forceful … And pointing the index finger is simply seen as rude and too aggressive.

But I’d seen this gesture before, and Obama hadn’t learnt it from a debating coach. Whether consciously or not, he was revealing his boyhood in the Indonesian island of Java, where it is considered impolite to point with your index finger. Seeing Obama point with his thumb in the debates confirmed something I had suspected for some time. Whatever else he might be, Obama is America’s first Javanese president.

Some time ago, I devoted a significant period of time and study to the traditions of Javanese kingship. I was writing a book called Obscure Kingdoms (1993) about traditions of kingship in non-Western societies, and I spent a period of time in Indonesia. One of the book’s chapters was about kingship in Java and, in the course of my research, I had become well-acquainted with a certain Javanese mannerism. I was struck to see that mannerism once again, uncannily echoed by Obama during the televised US presidential debates.

Unlike most political analysts, I see the imprint of Java in Obama far more than the imprint of Hawaii (where he was born and later went to high school); more than the imprint of Chicago (where he began his political career), and certainly more than Kenya (a highly popular notion that is particularly far-fetched). Indeed, it was in Java that Obama spent his childhood, had his primary education, and where his mother made her career. It was the country where his stepfather and his half-sister were born, and which he visited several times in his early adulthood. Obama still speaks some Indonesian.

Considerable time and energy has been spent speculating and theorising about Obama’s Kenyan background. There is a ridiculous book called The Roots of Obama’s Rage (2011) by Dinesh D’Souza. It’s a piece of popular controversialism which suggests that the key to understanding Obama — as a man and as a president — lies in his Kenyan background. Obama’s father, whom he barely knew, was a government economist in the early days of Kenyan independence. D’Souza argues that Obama inherited his father’s Kenyan anti-colonial mindset, and that this is what motivates Obama politically and informs how he sees the world.

Traditionally, the Javanese ruler triumphs over his adversary without even appearing to exert himself

Naturally, the idea caught on in the loony blogosphere, and as a result there are now millions of people in America who hold the view that Obama’s political approach is somehow ‘Kenyan’, and that by the end of Obama’s term of office the US will be governed according to a pernicious form of Kenyan socialism. Absurd, certainly, but then again there are also Americans who believe in black helicopters and alien abduction.

It’s true that Obama has written comparatively little about his time in Java in either of his books. His first autobiographical book, Dreams from My Father (1995), is principally about his search for Barack Obama Snr’s Kenyan roots. In fact, he only went to Kenya to research this book. The search for his African roots was important to him in his journey of self-discovery and self-invention, a process that was completed in his adoption of African-American cultural and social identity, and his choice of the black neighbourhoods of Chicago as the place where he began his political career. Part of the process of forging his own identity and his own path in life involved distinguishing himself from the world view of his mother, Ann Dunham, which was based on her international development work in Java. Most telling of all perhaps, when it comes to Obama’s own downplaying of his time in Java, was a comment in his second book, The Audacity of Hope (2006), in which he wrote: ‘Most Americans can’t locate Indonesia on a map.’

While Dreams from My Father was about the father who returned to Kenya when Barack was a baby, undoubtedly the strongest influence on Obama throughout his childhood was his mother. A truly extraordinary person, Dunham was an anthropologist who devoted her life to the study of small-scale industry in rural Java, while also working as a development economist and raising two children. When Barack was six, he and his mother moved from Hawaii, where he was born, to Jakarta, the Indonesian capital, where he spent the formative years of his childhood. It was in Java where Obama learnt and adopted the cool, calm, unflappable personal and presidential style that has earned him the nickname ‘No Drama Obama’. It’s a genuinely Javan ideal.

Anyone who has visited the island of Java will know what great value the Javanese people place on maintaining a serene demeanour, harmonious social relations, and not appearing visibly angry. Acutely aware of local norms of behaviour, Dunham made a point of ensuring that her son adopted Javanese manners. In his memoir, Obama recalls how his mother ‘always encouraged my rapid acculturation in Indonesia. It made me relatively self-sufficient, undemanding on a tight budget, and extremely well-mannered when compared with other American children. She taught me to disdain the blend of ignorance and arrogance that too often characterised Americans abroad.’

But this formative period entailed more than a process of pragmatic acculturation. In Janny Scott’s biography of Obama’s mother, A Singular Woman, one of her interviewees maintains: ‘This is where Barack learnt to be cool … if you get mad and react, you lose. If you learn to laugh and take it without any reaction, you win.’ What the young Barack had to take was being taunted by Indonesian children — his classmates and the children he played with in his Jakarta neighbourhood — for his dark skin colour. At first he was often thought of as an Indonesian from one of the outer (racially Melanesian) islands of the Indonesian archipelago. Yet of this period in Jakarta, Obama’s biographer David Maraniss wrote that the young Barack ‘had become so fluent in the manners and language of his new home that his friends mistook him for one of them’.

The Javanese have a word for this kind of bearing. They call it halus. The nearest literal equivalent in English might be ‘chivalrous’, which means not just finely mannered, but implies a complete code of noble behaviour and conduct. The American anthropologist Clifford Geertz, who wrote some of the most important studies of Javanese culture in English, defined halus in The Religion of Java (1976) as:

Formality of bearing, restraint of expression, and bodily self-discipline … spontaneity or naturalness of gesture or speech is fitting only for those ‘not yet Javanese’ — ie, the mad, the simple-minded, and children.

Even now, four decades after leaving Java, Obama exemplifies halus behaviour par excellence.

Halus is also the key characteristic of Javanese kingship, a tradition still followed by rulers of the modern state of Indonesia. During my period of study in Indonesia, I discovered that halus is the fundamental outward sign or proof of a ruler’s legitimacy. The tradition is described in ancient Javanese literature and in studies by modern anthropologists. The spirit of the halus ruler must burn with a constant flame, that is without (any outward) turbulence. In his classic essay, ‘The Idea of Power in Javanese Culture’ (1990), the Indonesian scholar Benedict Anderson describes the ruler’s halus as:

The quality of not being disturbed, spotted, uneven, or discoloured. Smoothness of spirit means self-control, smoothness of appearance means beauty and elegance, smoothness of behaviour means politeness and sensitivity. Conversely, the antithetical quality of being kasar means lack of control, irregularity, imbalance, disharmony, ugliness, coarseness, and impurity.

One can see the clear distinction between Obama’s ostensibly aloof style of political negotiation in contrast to the aggressive, backslapping, physically overbearing political style of a president such as Lyndon Johnson.

Traditionally, the Javanese ruler triumphs over his adversary without even appearing to exert himself. His adversary must have been defeated already, as a consequence of the ruler’s total command over natural and human forces. This is a common theme in traditional Javanese drama, where the halus hero effortlessly triumphs over his kasar (literally, unrefined or uncivilised) enemy. ‘In the traditional battle scenes,’ Anderson notes:

The contrast between the two becomes strikingly apparent in the slow, smooth, impassive and elegant movements of the satria [hero], who scarcely stirs from his place, and the acrobatic leaps, somersaults, shrieks, taunts, lunges, and rapid sallies of his demonic opponent. The clash is especially well-symbolised at the moment when the satria [hero] stands perfectly still, eyes downcast, apparently defenceless, while his demonic adversary repeatedly strikes at him with dagger, club, or sword — but to no avail. The concentrated power of the

satria [hero] makes him invulnerable.

Even to seem to exert himself is vulgar, yet he wins. This style of confrontation echoes that first famous live TV debate in the election of 2012 between Obama and Romney, in which Obama seemed passive, with eyes downcast, apparently defenceless (some alleged ‘broken’) in the face of his enemy, only to triumph in later debates and in the election itself.

Like a Javanese king, Obama has never taken on a political fight that he has not, arguably, already won

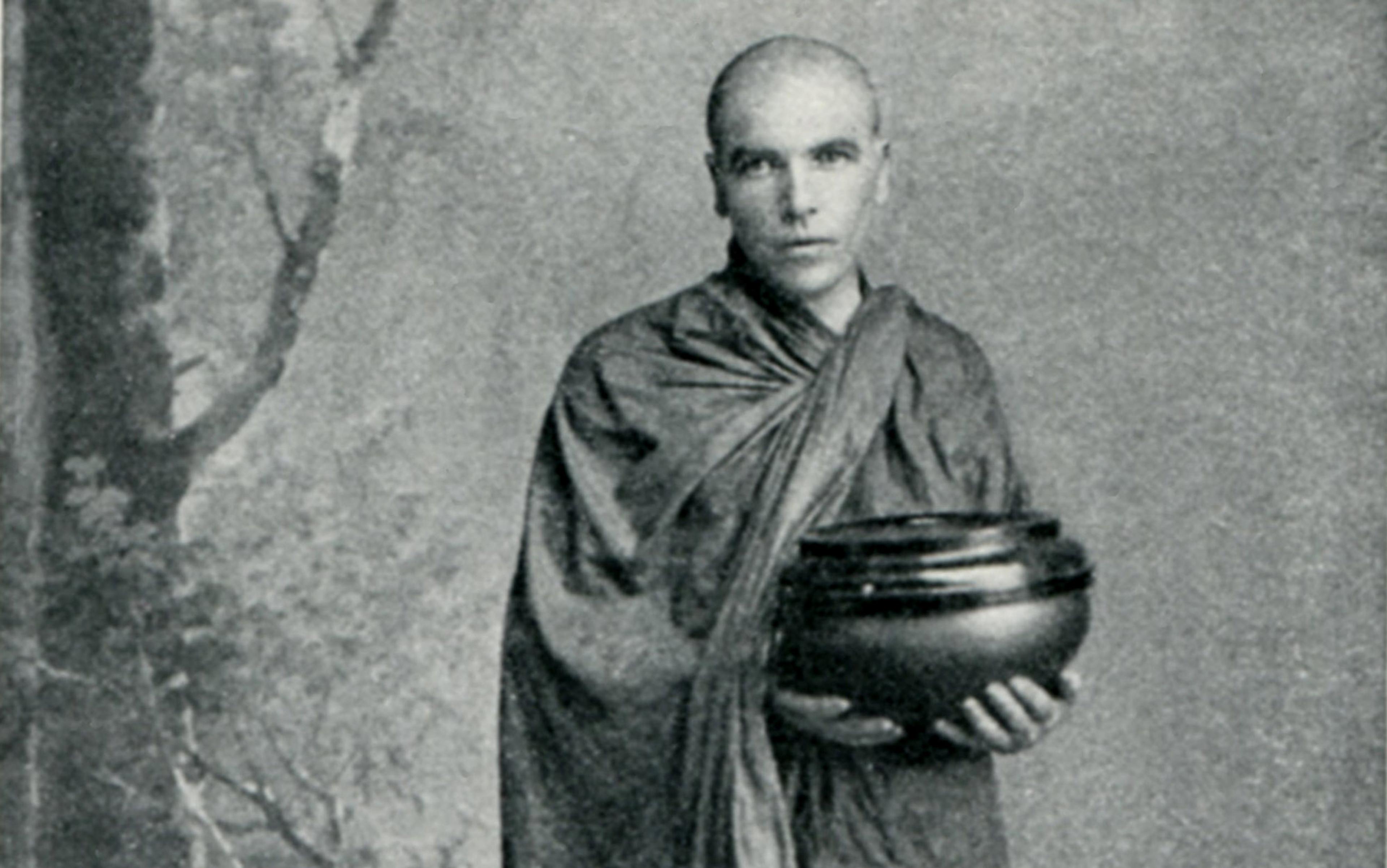

But such a disposition is not just external posturing. Halus in a Javanese ruler is the outward sign of a visible inner harmony which gathers and concentrates power in him personally. In the West, we might call this charisma. Crucially, in the Javanese idea of kingship, the ruler does not conquer opposing political forces, but absorbs them all under himself. In the words of Anderson again, the Javanese ruler has ‘the ability to contain opposites and to absorb his adversaries’. The goal is a unity of power that spreads throughout the kingdom. To allow a multiplicity of contending forces in the kingdom is a sign of weakness. Power is achieved through spiritual discipline — yoga-like and ascetic practices. The ruler seeks nothing for himself; if he acquires wealth, it is a by-product of power. To actively seek wealth is a spiritual weakness, as is selfishness or any other personal motive other than the good of the kingdom.

That’s the theory, though highly simplified. The modern Republic of Indonesia is in many ways the direct successor and continuation of the ancient Javanese kingdom. Java remains the political centre of an empire of islands. The first president of Indonesia, Sukarno, was inaugurated in 1945 in Yogyakarta, the Javanese city that remains the capital of the Javanese kingdom, in the very spot in the royal palace where the Sultans of Yogyakarta were crowned. Yogyakarta was briefly the capital of the Republic of Indonesia, and the Sultan of Yogyakarta was its second vice president. Sukarno began his term as president with a policy that combined communism, Islam and nationalism, a weird combination in Western terms, but one that makes sense in Javanese terms: in claiming ownership of these political forces, Sukarno was seeking to subjugate them and harmonise them under his own kinglike authority.

I can’t help but feel the parallels with Obama are striking. He dismayed many liberals in the first term of his presidency, by persisting in a political approach that sought to absorb the Republican Party — his political opponents — into his policy-making, just as Sukarno sought, at first, to absorb all political forces in Indonesia, and as the Javanese king absorbed all natural and human forces. Four years later, of course, with political dramas such as the fiscal cliff behind him, one can see an Obama that has adjusted to American political conditions; he is now playing American, not Javanese politics. But then again, like a Javanese king, Obama has never taken on a political fight that he has not, arguably, already won.

There is, however, another reason why I persist in looking at Obama in the context of traditional Javanese kingship. After Barack left Indonesia to attend high school in Hawaii, his mother Ann Dunham moved from Jakarta to the very cradle of Javanese civilisation, the compound of the palace (Kraton) of the Sultan of Yogyakarta, in central Java. The Kraton is the past and present home of Javanese kings; in recognition of the role of Sultan Hamengkubuwono VIII in the struggle for independence from Dutch colonial rule, the area around Yogyakarta was given special political status inside Indonesia, and the sultans retain political status within the Indonesian republic. Not only does the sultanate of Yogyakarta represent the theoretical and cultural model of government and political power in the modern state of Indonesia, the Kraton is the home of traditional Javanese culture. The Kraton’s walled compound — essentially, a densely populated urban village — is traditionally the residence of members of the royal family and of palace servants and officials. Foreigners are forbidden from living here, but Dunham secured the unusual privilege of being allowed to live there because her mother-in-law, Eyang Putri, the mother of her second husband, Lolo Soetoro, was believed to be a distant relative of the royal family and lived in the compound. Although the old lady was in very good health, Obama’s mother was allowed to move into her house in the palace compound for the nominal purpose of looking after her.

Let your opponent yell and scream, and listen politely

Now it might or might not be true that Dunham’s mother-in-law — Obama’s step-grandmother — was a blood relative of the Sultan. Maraniss, Obama’s biographer, found no evidence either way. But Obama’s stepfather believed it, as did Obama’s mother, and so did their daughter, Obama’s half-sister Maya Soetoro-Ng. This belief or family myth is by itself significant. It places the family firmly within the system of Javanese kingship. Growing up, in Java or back in Hawaii, Obama would have known about this connection and its meaning.

After leaving Java for his education, Obama visited his mother regularly over the years. The palace compound (bekel, in Javanese) is a beautiful place. While I was researching my book on non-Western traditions of kingship, I would walk around it in the evenings, glimpsing the interiors of the houses, with their green and pink glowing aquariums, and blue and grey glowing televisions. Stars could be seen through the palm-tree branches, the air was filled with birdsong. I looked back at my own book and found the following reflection of the place: ‘Tourists are forbidden from staying here, but a few academic researchers had managed it, and I envied them.’ I didn’t know then about Dunham.

As Obama entered adulthood, he sought to create a new identity for himself that was based on an American and, within that, a black American identity. He distanced himself from what he saw as his mother’s ‘internationalist idealism’. But the influence of Javanese ways remained, unconsciously perhaps, a crucial part of him. When he was a community organiser in Chicago, working with black churches and local institutions, people noticed his unusual tendency to prefer harmony to confrontation, to bringing all forces together under his quiet leadership. Maraniss quotes an informant who was present at a meeting of church leaders when one of the leaders attacked Obama as a ‘do-gooding outsider’:

To Barack’s credit, he didn’t get up from the back of the room and come to defend himself. He left it there and let the guy say what he needed to say …. Barack absorbed it. But then, as soon as it was over, he waited until the guy left, and said, ‘Now, what just happened? Let’s make sure we understand what just went on so we can go from here.’ Civility, being respectful, was always very important to him.

He would use this same technique again and again in later political conflicts: let your opponent yell and scream, listen politely, and then, when your adversary has exhausted himself, somehow end up winning. Indeed, that is halus through and through.

*This article was amended on 7th February 2013. It should have stated that the Sultan of Yogyakarta was the second vice president, rather than the first.