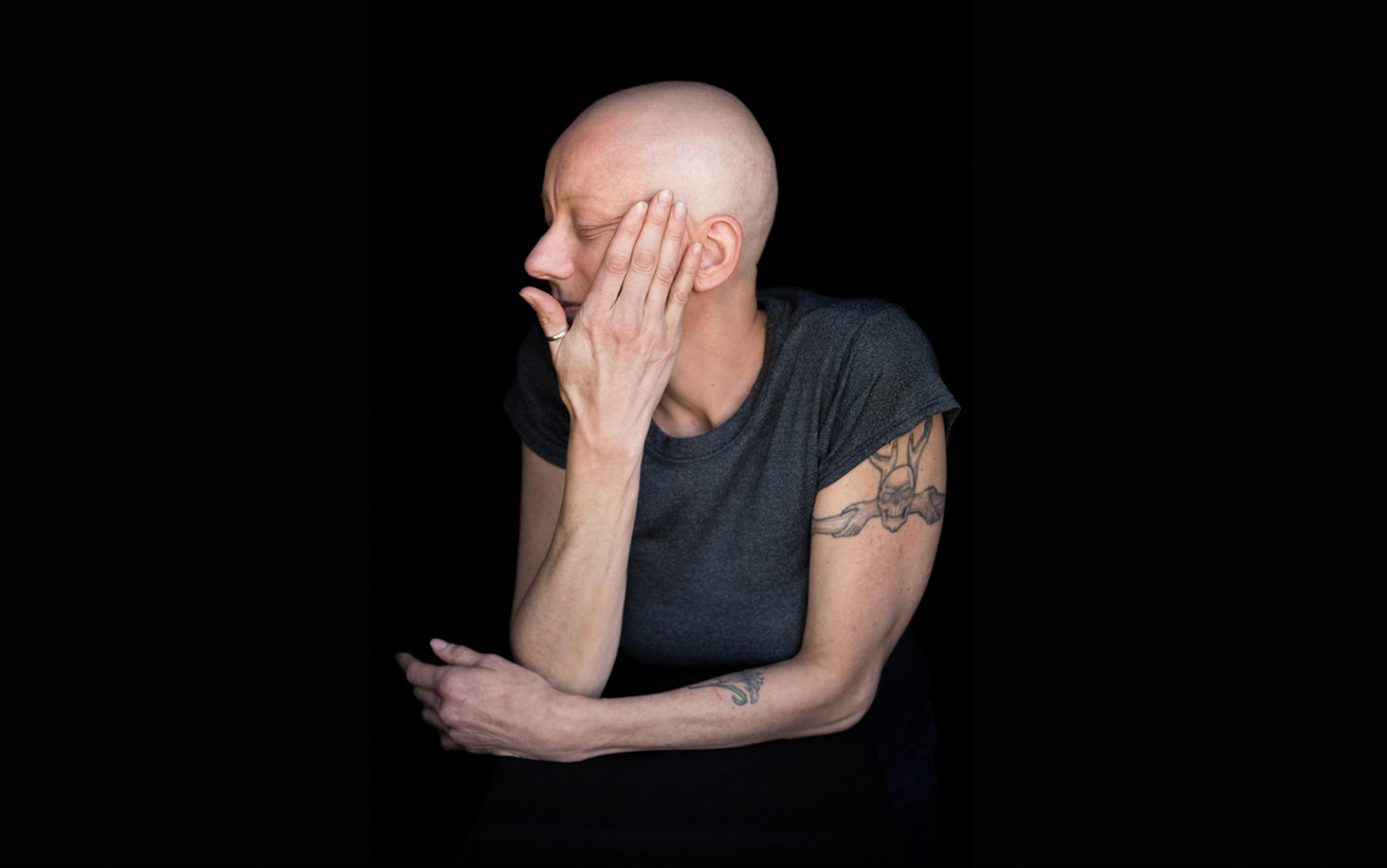

Every month or so, I see a patient called Fraser in my primary care clinic, a soldier who was deployed in Afghanistan. Fifteen years after coming home, he is still haunted by flashbacks of burning buildings and sniper fire. He doesn’t work, rarely goes out, sleeps poorly, and to relieve his emotional anguish he sometimes slices at his own forearms. Since leaving the army, he has never had a girlfriend. Fraser was once thickly muscled, but weight has fallen off him: self-neglect has robbed him of strength and self-confidence. Prescription drugs fail to fully quieten the terror that trembles in his mind. Whenever I used to see him in clinic, he’d sit on the edge of his seat, shakily mopping sweat from his forehead and temples. I’d listen to his stories, tweak his medications, and tentatively offer advice.

When Fraser began coming to see me, I was reading Redeployment (2014) by Phil Klay – short stories about US military operations, not in Afghanistan, but in Iraq. No book can substitute for direct experience, but Klay’s stories gave me a way to start talking about what Fraser was going through; when I finished the book, I offered it to him. He found reassurance in what I’d found illuminating; our conversations took new directions as we discussed aspects of the book. His road will be a long one, but I’m convinced those stories have played a part, however modest, in his recovery.

It’s said that literature helps us to explore ways of being human, grants glimpses of lives beyond our own, aids empathy with others, alleviates distress, and widens our circle of awareness. The same could be said of clinical practice in all of its manifestations: nursing to surgery, psychotherapy to physiotherapy. An awareness of literature can aid the practice of medicine, just as clinical experience certainly helps me in the writing of my books. I’ve come to see the two disciplines as having more parallels than differences, and I’d like to argue they share a kind of synergy.

Patients spend more time with a writer than they can ever spend with their physician, and the hours it takes someone to read and reflect on a book can be time well-spent. Redeployment might have eased some of Fraser’s bewilderment and isolation, but by breaking down a boundary of experience it also helped me to understand a little more of what he had been through. There are numberless other books that do the same. William Styron’s Darkness Visible (1990) offers an eloquent testimony of how it feels to suffer severe depression, and I’ve seen it give sufferers a promise and an encouragement that they, like Styron, might find a way back to the light. The list of books I’ve discussed with patients over the years is as plural as the humanity that pours through the clinic: Ray Robinson’s Electricity (2006) when talking about life with severe epilepsy; Annie Dillard’s The Abundance (2016) while exploring the place of wonder in sustaining our lives; Andrew Solomon’s Far from the Tree (2014) on the challenges of caring for a disabled child; Ben Okri’s poem ‘To an English Friend in Africa’ (1992) in a discussion of the trials and rewards of NGO work.

There are parallels between generating and appreciating lasting stories and art, and generating and appreciating healing, therapeutic encounters. Both are helped by adopting the same attitude of open curiosity, of creative engagement, of seeking to empathise with the predicament of the other, of tapping into the wider context of human lives. The doctor, like the writer, works best when she’s alive to the subtlety of individual experience, and is able at the same time to see that individual in his or her social context.

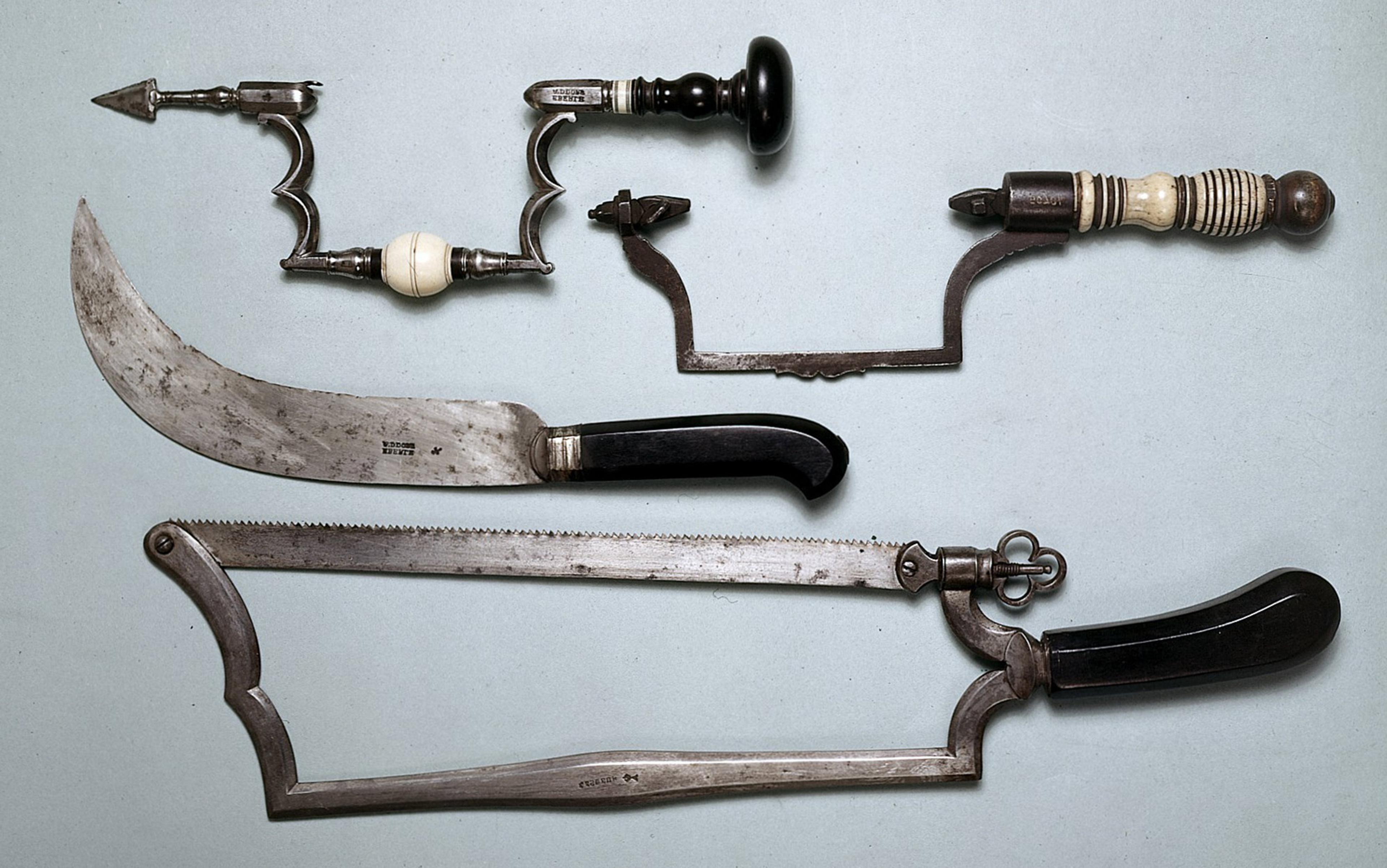

If it’s true that readers make better doctors, and literature helps medicine, it’s worth asking if the relationship is reciprocal – does the practice of medicine have something to offer literature? Certainly, the stories doctors hear take the pulse of a society. Clinicians are often confessors, bound to confidentiality and privy to a community’s secrets in the way that priests once were. More than 300 years ago, Robert Burton in The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) equated priests with doctors when he said that ‘a good divine either is or ought to be a good physician’; the French novelist Rabelais was both.

In former centuries, the two professions offered the same unfiltered exposure to a cross-section of society, the same professional duty to stand witness over life’s crises, and to reckon with questions of purpose and futility that are of urgent relevance to literature. Burton’s contemporary John Donne (also a clergyman) wrote a series of poetic meditations following his own narrow survival from life-threatening illness. The most famous of these, ‘Devotions upon Emergent Occasions’ (1624), confirms that proximity to death can reinforce a sense of belonging to a community of humanity:

any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankinde;

And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

If it’s going to be effective, clinical practice requires a highly trained attentiveness to verbal and non-verbal streams of information. Clinicians of all kinds sieve details ceaselessly from the words and bodies of their patients. And we also expect clinicians to see through the fake narratives we live by – to act as translators and literary critics of the stories we project to the world.

‘There’s no need for fiction in medicine,’ wrote Arthur Conan Doyle in Round the Red Lamp (1894), ‘the facts will always beat anything you can fancy.’ The trajectories of our lives can be as tumultuous or unexpected as any story or movie but will, at the same time, follow the patterns of those archetypal stories we learn in the nursery or see at the cinema. What does the writer do but name and articulate patterns and archetypes of experience, and offer them to the reader to be recognised? And what does the clinician do but offer recognition to the patient’s story – to say ‘your suffering has a name’, and in its naming, attempt to tame it?

the language we use to articulate pain has the power to transform our experience of it

In its use of metaphor, the best writing offers a kind of enchantment, transforming our perspective and helping us to make sense of the world, from Homer’s ‘rosy-fingered dawn’ to Dylan Thomas’s ‘bible-black’ night. A deeper engagement with literature can help clinicians with the metaphors they use: if a cancer is incurable, it doesn’t make sense to think of it as a monster to be defeated but as an inner ecology to be held in balance. When he was diagnosed with prostate cancer, Anatole Broyard, a former editor at The New York Times Book Review, said that he wanted his physician to spin metaphors that would reconcile him to his condition: ‘The doctor could use almost anything,’ he wrote in Intoxicated by My Illness (1992). ‘“Art burned up your body with beauty and truth.” Or “You’ve spent your self like a philanthropist who gives all his money away.”’ Broyard wanted language to conjure dignity from illness, to help him ‘look upon the ruin of his body as tourists look upon the great ruins of antiquity’.

In her poetic and careful study of vaccination, On Immunity (2014), Eula Biss showed how the human immune system is better compared to a well-maintained garden than a militia. War metaphors in health and healing can be valid, but bring different ideas to the mind of each patient – an appreciation of storytelling can assist physicians to choose the metaphor that will best help their patients, and also help patients articulate inner experience to their physicians. Pain descriptions are the most vivid daily example of our tendency to metaphorise experience – next time you have a pain, think about whether it’s ‘stabbing’ or ‘ripping’, ‘throbbing’ or ‘aching’. The nerves perceiving the pain communicate none of these things, but studies have shown that the language we use to articulate pain has the power to transform our experience of it.

In his autobiographical essay The Practice (1951), the poet and general practitioner William Carlos Williams wrote that medicine’s clamour and diversity can, if approached in the right spirit, be inspirational and even restorative. Medicine nourished Carlos Williams’s sense as a writer of what it means to be human, and offered the very lexicon he used to write:

Was I not interested in man? There the thing was, right in front of me. I could touch it, smell it … it was giving me terms, basic terms with which I could spell out matters as profound as I cared to think of.

Sigmund Freud noticed that doctors’ choice of vocabulary has always influenced the way people understand and come to terms with illness: ‘All physicians, therefore, yourselves included, are continually practising psychotherapy, even when you have no intention of doing so and are not aware of it.’ He asked whether clinicians might not be more effective if they were able to understand the power of words, and resolve to wield that power more effectively.

At the heart of both physicians’ and writers’ work is a will to imagine and recognise the patterns of our lives, and ease its dissonances. But there’s a crucial difference: writers and readers have the liberty to lose themselves in their world of characters and plotlines, while clinicians must remain perceptive, attentive and, crucially, keep to time. Physicians who give themselves up entirely to the suffering of their patients risk burnout. This is the Faustian pact at the heart of the contract between physicians and their patients – to be offered limitless experience of the plurality of humanity, but at the risk of exhausting compassion in a way that’s less relevant for the writer.

Neuroscientific research suggests that the more closely you empathise with someone in mental or physical pain, the more your brain behaves as if you’re in pain yourself. When compassionate attitudes are gauged in new medical students, junior doctors and more senior trainees all the way up to those on the verge of retirement, they have been seen to drop stepwise with age and experience, as if the practice of medicine brings with it a cargo of such mental and emotional weight that some clinicians become overburdened.

Abraham Verghese, the Stanford physician and novelist, has observed ‘what we need in medical schools is not to teach empathy as much as to preserve it’. The weight of clinical practice can be overwhelming for some – that’s why more doctors in the West are working part-time and retiring earlier than ever before. But the profession’s very multiplicity offers insights and inspirations, satisfactions and consolations, available in few other others.

20 years into my medical career, medicine and literature can feel like the verso and recto of a single page

In an interview for the BBC in 1962, Sylvia Plath said: ‘I would like to have been a doctor … somebody who deals directly with human experiences, is able to cure, to mend, to help.’ She explicitly contrasted clinicians’ ‘mastery of the practical’ with her life as a poet where, she complained, she felt as if ‘one lives a bit on air’. As a child, she played at doctors, and as an adolescent, she attended births and watched human dissections. But she baulked at the discipline involved in medical training, and worried its burdens would have been too much.

Those burdens are real, and doctors have to find ways of bearing them. I’m now 20 years into my medical career, and medicine and literature have sometimes felt like the verso and recto of a single page, at other times the left and right foot of a steady gait, but neither of those metaphors carries the sense of heaviness that medical work can bring, which a love of literature can leaven. As I look forward to the next 20 years of medical practice, I know that the burden of stories will get heavier, but prefer to imagine that weight as ballast, and the airy, poetic quality of literature as wind in the sails. If the two can work together, there’s a limitless ocean of humanity out there to explore.

This is an edited extract from the 2016 Sheridan Lecture on Medicine and Literature, delivered at Brown University, Providence.