Do nights have a history to tell? How would the history of the working-class nights look? This question drove me to research the lives of the 19th-century labouring poor in colonial India. Following the French philosopher Jacques Rancière’s Proletarian Nights: The Workers’ Dream in Nineteenth-Century France (1981), I wanted to know what the 19th-century labouring poor, especially the cotton textile mill workers of Bombay who worked for 13 or 14 hours a day, did at night. Did they just go to bed or did they socialise with friends, roaming the streets of the city?

We know a lot about the daytime lives of workers. Historians of capitalism, slavery, labour and commodities have favoured the daytime. But that’s only half the story – the other half of our lives is spent at night. Nights are critical to the history of capitalism and labour: control over the night-time was a political act for workers. It asserted their dignity as independent beings. Night was where workers dreamed and pursued their own visions, both together and as individuals.

During the 17th century, the meanings of the night and nightlife in Europe fundamentally changed. In the move towards industrialisation, the night generated new notions and practices of religious experience, a new kind of crime world, as well as new public and private spaces, court culture, witchcraft trials, regulation and policing (through street lights). In Evenings’s Empire (2012), the historian Craig Koslofsky calls it the colonisation of the night: the way urban people slept, socialised and worked radically changed from the early modern period. Artificial lights stretched the daytime realm into the night. Many activities that required light were now possible after dark too. Rural people continued to sleep as humans long had, where the evening slumber is divided in two. But urban people shifted to a single sleep of seven to eight hours. A greater demarcation developed between the day and the night, especially in cities. Night stood for repose, and day for labour. This was not the case before industrialisation. In craft and artisanal work, people had task- or nature-oriented notions of time.

Disciplined industrial capitalism reversed time and work, and people had to master timed notions of work and life, as the British historian E P Thompson showed in 1967. Clocks and timekeeping proliferated and acquired new authority. It took fines, penalties, bells, schooling, workshop clerks and preaching to affect new practices of work life separated from the usual everyday social life (sleeping, chatting, family time). Industrial capitalism required workers to remain attentive, efficient and committed at the shop floor. In the case of colonial Bombay, the capitalist employers’ project was especially incoherent. They did not demarcate the clear boundaries of work and leisure. It was workers who demanded a fixed and timed notion of work.

Bombay’s cotton mills took off in the 1850s. Poor construction and sanitation made mill compounds unhygienic. Cotton floating in the air was suffocating, and running boilers made them hot. Depending on how one counted, cotton-factory workers in the decades 1850-90 laboured between 13 to 16 hours per day. During the winter, mills relied on gaslight to lengthen the workday. Only in the first decades of the 20th century did nightshifts become common when the majority of mills installed electric lights. Workers and employers constantly fought over the boundary between work and leisure. Employers complained that leisure intruded into the working hours, and workers complained that work intruded into their free time.

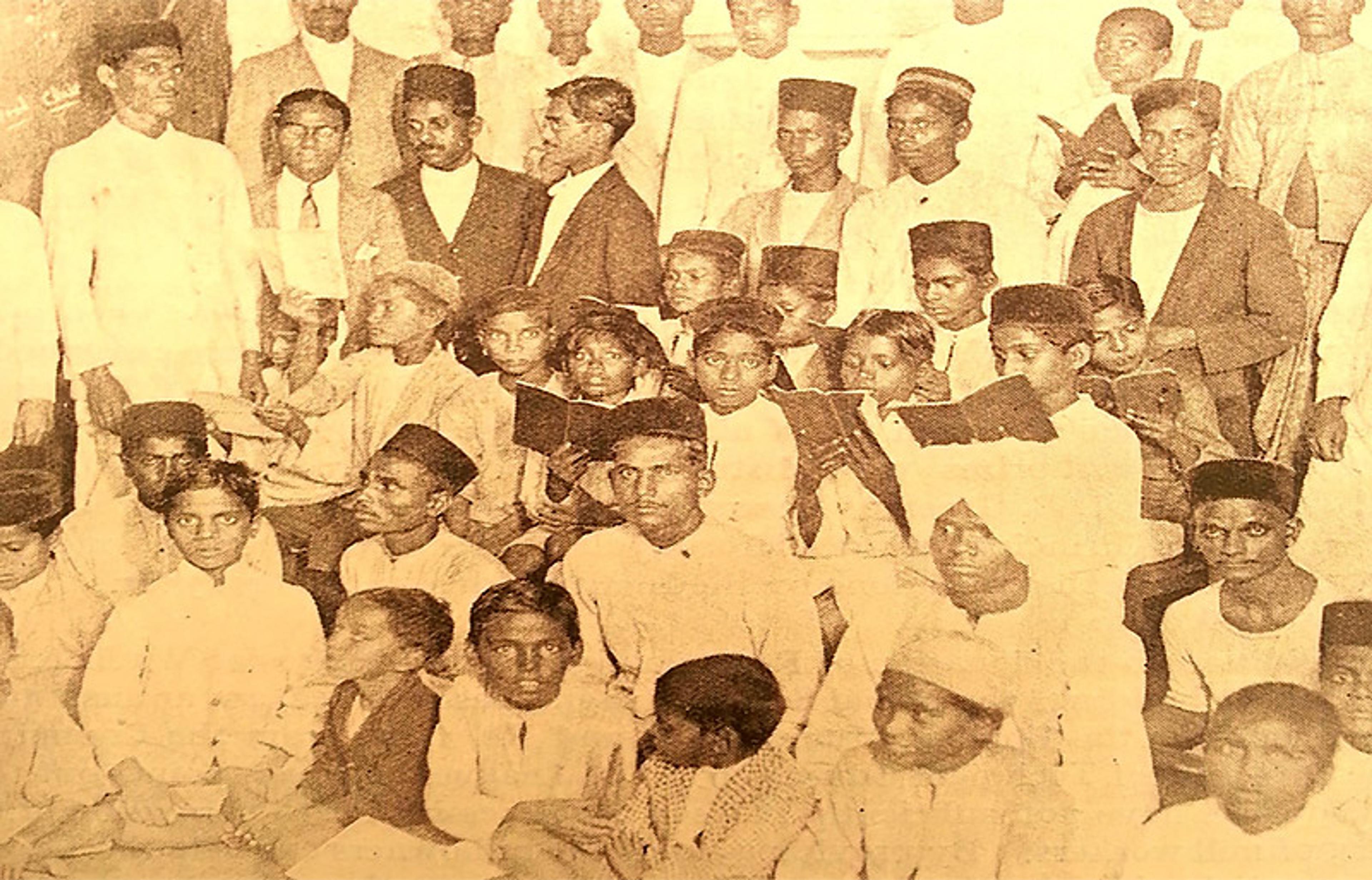

Teachers and pupils in a night school. From Bombay Industries by S M Rutnagur, p514. Photo supplied by the author

For the majority of workers, the day began at 5:30am, and stopped when it was too dark to work. In 1890, to arrive at the factory gates at 5:30am, Babajee Mahdoo woke at 3am. When A Alwe joined the mill as a half-timer in the 1910s, full-timers worked for 16 hours between 5am and 9pm; to get ready for work, adults rose at 4am. The cotton-production process knew neither night nor day however: any intrusion in the cycle was a disruption. From the employers’ perspective, when their employees drank alcohol, gambled, engaged in labour politics or fell ill and missed the next day’s work, they compromised the commodity cycle.

For women working in Bombay’s cotton factories, the experience was even more rigorous. They worked both at home and on the shop floor. In 1890, Doorpathee, a worker and mother, would wake at 3am to take a quick bath, collect water for the whole day, cook food for herself and her daughter, and walk 1.5 miles in the dark to reach the factory gate. A study from 1933 found out that working women living in chawls (typical working-class one-room housing) woke first to collect water from the common tap and then to fire cow-dung cakes and cook; as the report put it, ‘after such a … morning, they have to go to their respective mills and to work in their stuffy atmosphere till the evening’. Factories also tried to steal workers’ free time. They required employees to clean machines on Sundays, and confiscated wages for lateness, missed work and ‘bad’ quality yarn or clothes.

Like Alwe, the majority of Bombay’s cotton-factory workers were migrants from rural and coastal western India. City and factory life were both new to them. Living in Bombay and submitting to what Thompson called the ‘time discipline’ of industrial capitalism must have been a huge mental and physical strain. In the country, the terms of their working life were dictated by seasonal changes, the rhythms of sowing and harvesting, or the fluctuating demand for artisanal goods. Industrial discipline attempted to take over everything yet there were no fixed hours of work in factories. While employers tried to regulate labour hours, the time discipline of their own production process was not fixed. Some worked for 12 or 13 hours, and others for 14 or 15; some factories closed down during the slump, and others continued to run; some installed electricity, and others continued to work on with gaslights. Workers were very much confused about these mixed work practices within one single city, and the first demand to discipline the time of factories came from them.

It was dark when they left for work, dark when they got home: they forgot what their children looked like

In front of the commissions appointed to regulate factory working conditions, workers demanded that the night be kept away from the working day. Night united them. Otherwise, work intruded into their family and social time. About 5,000 workers signed a memorandum submitted to the 1884 Factory Commission. It was the first living exhibit of their collective consciousness in Bombay. The worker collective dictated that they would like to work from dawn to dusk, and not in the dark. Their demands included a half-hour recess at noon, Sunday as a rest day, and wage payment before the 15th day of the next month. These were bold demands in those times of no welfare regime and the British colonial state siding by the rich employers. Individual dismissals, everyday workplace harassment and wage punishments were problems in the absence of any regulatory mechanism.

In workers’ testimonies, we get a sense of how they calculated their workday. It was radically different from how employers measured it. For workers, the time spent preparing for work was part of the workday, for example, walking to the factory in the dark and waiting at the factory gates to avoid late-arrival fines. As a result, workers could not spend any time with their children, wives and friends. Workers in 1885 specifically complained that, as it was always dark when they left for work and dark when they arrived back home, they had forgotten what the faces of their children looked like.

Employers were not worried about these issues. They often told the factory commissions that the time workers spent at the site was not equal to the real working hours: workers took naps, visited latrines for smoking and resting, read bhajan books, and took unannounced leave. One mill employer remarked: ‘Workers do not work all the time; they may be sitting down in one of the departments, they may be sleeping – and I myself have seen some sleeping – or they may have their meals.’

In such an environment, where fines and firing were common disciplinary measures, workers created tiny spaces of relief and socialisation for themselves. Queuing to collect the water from the common pump at dawn was also a time when workers got together and nurtured social ties. They chatted about the cruelty of the employer, their children’s futures or the newly arrived migrant, as well as minimum wages, sex scandals and love affairs.

The first two factory acts, one in 1881 and the other in 1891, neglected to shorten working hours. When the 1890 Factory Commission gathered workers’ voices, both male and female workers overwhelmingly demanded a shorter working day. Doorpathee told the commission: ‘It will be better if the hours are shortened.’ The 1891 Factory Act declared Sunday a holiday, limited the work day to 11 hours for female workers and seven hours for child workers (aged between nine and 14). But it left out adult males from the ambit of a shorter work day, and men continued to work between 13 to 16 hours per day.

In 1890, a Times of India correspondent reported: ‘A great many of the labouring classes had a great difficulty in making both ends meet; and when they managed somehow to send their children to these [night] schools, they sent them with the object of giving them a rise in life, which showed that they appreciated the advantage of learning.’

While workers fought battles against employers for a shorter workday, they were also attending night schools established in cooperation with social-reform organisations. As soon as the mills closed and the dusk descended, many workers turned into students. Though tired, many went straight to night school at 7pm, and spent two hours enjoying the pleasure of reading, listening to the teacher and holding a book. The night became reserved for aspiring.

The Theistic Association, a prominent socioreligious reform body of the Prarthana Samaj, a movement of liberal, middle-class Hindus that promoted belief in one god, established night schools in the 1890s for the purpose of educating the labouring masses and improving the mental and physical conditions of working migrants. Influenced by the approach of English reformers to the industrial poor, the educated, middle-class Theistic Association feared that Bombay’s migrant poor might soon emerge as a big social problem. The association wanted to help bring order to the city, and it travelled to working-class neighbourhoods to establish night schools in Kalbadevi in 1876, Girgaum in 1880, and Gamdevi in 1881. Students here included mill workers, day labourers, domestic servants and petty shopkeepers between the ages of 12 and 35. Even though the schools charged a fee of one anna (a 16th of a rupee), the labouring poor crowded the schools. By 1889, three further schools opened. Between 1886 and 1890, about 2,750 workers in total had studied at these night schools.

The demand for night schools was so acute by 1890 that individuals and other social-reform bodies followed the Theistic Association to open new schools, and the Theistic Association continued to expand. It soon established nine schools in different working-class neighbourhoods, including Thakurdwar, Khetwadi, Dongri and Byculla. About 565 students attended these schools daily for two hours per night. By 1912, more than 26,000 worker-students had passed through these institutions.

His schools disrupted the partitioning of the day as a time of work, and night as a time of rest

The history of the first working-class night school tells us what the night meant to workers. Established in 1874 by Bhiwa Ramji Nare, himself a worker, the school was financed for decades from his own salary. While there is no definite information on Nare’s social background and whether he was married or had kids, or what he taught in the school, we do know that he started his career as an ordinary worker on Rs 8 (rupees) per month in the Dinshaw Petit Mill. Nare worked in the mill industry for 37 years, and retired as a master-weaver from the Morarji Goculdas Mill on Rs 250 per month. He was probably one of the earliest labour leaders who mobilised workers politically and intellectually.

Early in the social history of the factory, he recognised the need for a formal school for workers and their children. Nare’s schools disturbed the life that employers wanted for their workers. His schools disrupted the partitioning of the day as a time of work, and night as a time of rest. By constantly absenting themselves from mills, sending their children to schools and mobilising workers for pressing grievances, workers learned to question the rules of the industrial life in which they found themselves caught. The time discipline taught by the industrial world had to be unlearned by workers.

Nare’s schools generated a politics of intellect in the working-class neighbourhoods and threatened to collapse the ‘natural’ distinctions of society. At that point, hardly any employer was interested in educating the workers. The Indian Textile Journal wrote: ‘Nare was a man in 10,000 giving his leisure time to conducting a school for the children of mill-hands.’ But the editor of the journal also detested Nare’s efforts to intellectualise and politicise the working class: ‘The Indian operative is no more fit for Trade Unions than he is for scientific education or ever reading and writing. He has to first learn things that are much more necessary, touching his daily life and work.’ The journal reasserted the dominant view that the realm of workers was hard, manual labour; it was not education, not politics, and not intellect.

Nare’s activism was not limited to one school. In 1887, with the help of his worker friends, he expanded the night school into a free day school for workers in the Mararji’s Chawl in Parel. He named the school Nare and Mandali’s Free School, advertising its free education policy. The school grew to be popular, and continued after Nare’s death in 1917. Encouraged by the enthusiastic response towards education among workers, Nare established two more schools, but he could not maintain them following his 1906 retirement. By now, Nare was a public leader and a representative of workers’ voices. He founded the Kamgar Hitwardhak Union (KHU) in 1909 and served as its president for eight years. Emerging as one of the earliest loose trade unions, the KHU helped workers in financial distress, unionised them, provided legal support, mediated their concerns with the mill management, opened schools and promoted temperance. Along with Nare’s schools, the KHU also ran a Marathi language night school.

By 1911, work hours for adult men in Bombay’s factories were reduced to 12 hours, and for children to six. While workers did not wait for a shorter working day to attend schools, the Factory Act of 1911 gave them a bit more time to attend night schools and use libraries. The number of worker-students grew. The Times of India in 1911 calculated that about 2,000 people attended night schools daily in Bombay. By 1919, it reported that the city had about 50 night schools, with an average daily attendance of 1,200 to 1,500 students. Meanwhile, according to the municipal records, by 1922 there were 33 night schools with an average of 1,136 students.

What drove workers to these night schools at the expense of much-needed sleep? There are no direct answers in the archives: the night-school workers have not left any of their writings. But it appears they wanted to change their social and economic condition. The colonial economy in India required a large number of educated and literate clerks, postmen, compositors, teachers, supervisors and overseers. Poor workers, coming from villages and lower-caste backgrounds, aspired to rise to these positions. Unlike manual labour, the requirement of literacy made these kinds of petit bourgeois positions socially respectable.

In contrast, social and economic elites defined workers as an illiterate and ignorant class. They used illiteracy to ‘explain’ the workers’ lack of commitment, militant behaviour, inefficiency and poverty. For a long time, both the colonial state and employers maintained this rhetoric to deny education, free time and higher wages to workers. Many scholars accepted these notions and continued to consider Indian workers as a predominantly illiterate force. But the night schools called the workers’ presumed illiteracy into question. There, we can begin to understand the workers’ dreams for emancipation from an enslaved life, their efforts to transcend their everyday exploited selves.

Bombay’s cotton workers traversed two worlds: the world of manual labour and of education. For them, the two were not fundamentally separated, as elites would have preferred them to be. Commenting on the enthusiasm of the student workers, The Times of India marvelled at ‘how low-paid workers who somehow or other are able to maintain themselves and their families, [are] attending these night schools so enthusiastically instead of enjoying their well-earned rest’.

Workers used the night to discover their subordinated existence and liberate themselves from exploitation by their employer. Instead of resting and completing the cycle of commodity production, they used the night to socialise and have new experiences – going to night school, or to the theatre, cinema, Bhajan mandali (religious gatherings) and lantern slide shows, drinking alcohol or roaming in the newly electrified streets of Bombay: these were all part of their nights. While the day symbolised bondage and humiliation, the night brought workers freedom, passion and dignity. And to acquire it, they were willing to fight employers, patriarchal family heads and the state. For Bombay workers, the overcrowded chawls and poor sleeping arrangements meant that night also had its discomforts. But overcoming these constraints made enslaved lives liveable. Workers slept and snored in the classroom, and yet stubbornly attended to their education.

They believed that education would allow them to dream and aspire for an economically secure life. It would move them and their children from the drudgery of manual labour that caste and poverty had imposed on their lives. Workers knew that their education was limited, short-lived, and different from the elites. And, it might not lead to a better material status. But then they would be known as ‘literate workers’.