It is 4.18am. In the fireplace, where logs burned, there are now orange lumps that will soon be ash. Orion the Hunter is above the hill. Taurus, a sparkling V, is directly overhead, pointing to the Seven Sisters. Sirius, one of Orion’s heel dogs, is pumping red-blue-violet, like a galactic disco ball. As the night moves on, the old dog will set into the hill.

It is 4.18am and I am awake. Such early waking is often viewed as a disorder, a glitch in the body’s natural rhythm – a sign of depression or anxiety. It is true that when I wake at 4am I have a whirring mind. And, even though I am a happy person, if I lie in the dark my thoughts veer towards worry. I have found it better to get up than to lie in bed teetering on the edge of nocturnal lunacy.

If I write in these small hours, black thoughts become clear and colourful. They form themselves into words and sentences, hook one to the next – like elephants walking trunk to tail. My brain works differently at this time of night; I can only write, I cannot edit. I can only add, I cannot take away. I need my day-brain for finesse. I will work for several hours and then go back to bed.

All humans, animals, insects and birds have clocks inside, biological devices controlled by genes, proteins and molecular cascades. These inner clocks are connected to the ceaseless yet varying cycle of light and dark caused by the rotation and tilt of our planet. They drive primal physiological, neural and behavioural systems according to a roughly 24-hour cycle, otherwise known as our circadian rhythm, affecting our moods, desires, appetites, sleep patterns, and sense of the passage of time.

The Romans, Greeks and Incas woke up without iPhone alarms or digital radio clocks. Nature was their timekeeper: the rise of the sun, the dawn chorus, the needs of the field or livestock. Sundials and hourglasses recorded the passage of time until the 14th century when the first mechanical clocks were erected on churches and monasteries. By the 1800s, mechanical timepieces were widely worn on neck chains, wrists or lapels; appointments could be made and meal- or bed-times set.

Societies built around industrialisation and clock-time brought with them urgency and the concept of being ‘on time’ or having ‘wasted time’. Clock-time became increasingly out of synch with natural time, yet light and dark still dictated our working day and social structures.

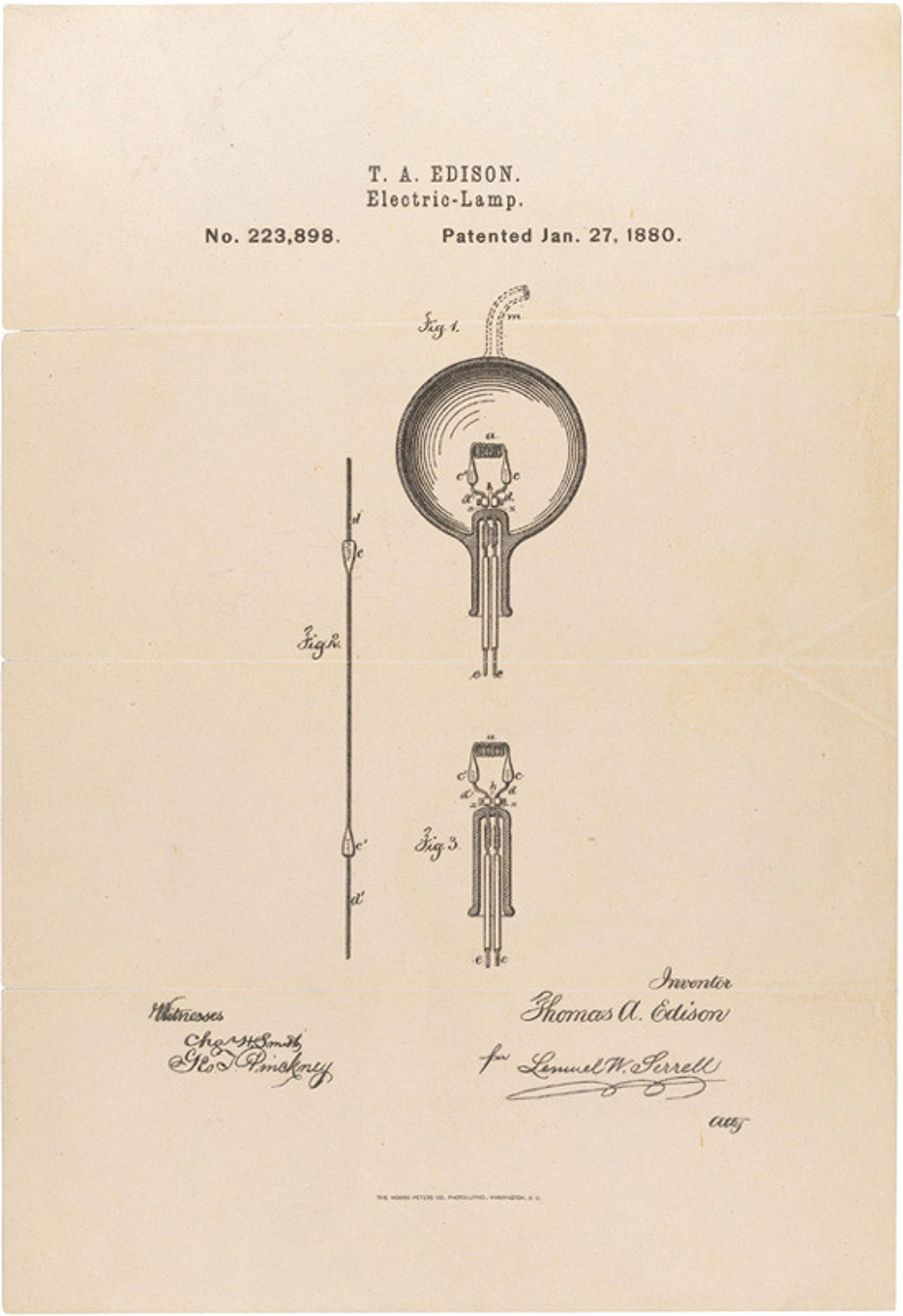

Then, in the late 19th century, everything changed.

The lights got turned on.

Modern, electrical illumination revolutionised the night and, in turn, sleep. Prior to Edison, says the Virginia Tech historian A Roger Ekirch, author of At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past (2005), sleep had been divided into two distinct segments, separated by a period of night-waking that lasted between one and several hours. The pattern was called segmented sleep.

Sleep patterns of the past might surprise us today. While we might think that our circadian rhythm should wake us only as the sun rises, many animals and insects do not sleep in one uninterrupted block but in chunks of several hours at a time or in two distinct segments. Ekirch believes that humans, left to sleep naturally, would not sleep in a consolidated block either.

His arguments are based on 16 years of research during which he studied hundreds of historical documents from ancient to modern times, including diaries, court records, medical books and literature. He identified countless references to ‘first’ and ‘second’ sleeps in English. Other languages also describe this pattern, for example, premier sommeil in French, primo sonno in Italian and primo somno in Latin. It was the ordinariness of the allusions to segmented sleeping that led Ekirch to conclude this pattern was once common, an everyday cycle of sleeping and waking.

Before electric lighting, night was associated with crime and fear – people stayed inside and went early to bed. The time of their first sleep varied with season and social class, but usually commenced a couple of hours after dusk and lasted for three or four hours until, in the middle of the night, people naturally woke up. Prior to electric lighting, wealthier households often had other forms of artificial light – for instance, gas lamps – and in turn went to bed later. Interestingly, Ekirch found less reference to segmented sleep in personal papers from such households.

For those who indulged, however, night-waking was used for activities such as reading, praying and writing, untangling dreams, talking to sleeping partners or making love. As Ekirch points out, after a hard day of labouring, people were often too tired for amorous activities at ‘first’ bedtime (which might strike a chord with many busy people today) but, when they woke in the night, our ancestors were refreshed and ready for action. After various nocturnal activities, people became drowsy again and slipped into their second sleep cycle (also for three or four hours) before rising to a new day. We too can imagine, for example, going to bed at 9pm on a winter night, waking at midnight, reading and chatting until around 2am, then sleeping again until 6am.

in the dead of night, drowsy brains can conjure up new ideas from the debris of dreams and apply them to our creative pursuits

Ekirch found that references to these two sleeps had all but disappeared by the early 20th century. Electricity greatly extended light exposure, and daytime activities stretched into night; illuminated streets were safer and it became fashionable to be out socialising. Bedtimes got later and night-waking, incompatible with an extended day, was squeezed out. Ekirch believes that we lost not only night-waking, but its special qualities, too.

Night-waking, he told me, was different in nature from waking during the day, at least according to the documents he found. The third US president Thomas Jefferson, for example, read books on moral philosophy before bed so that he could ‘ruminate’ over them between his two sleeps. The 17th-century English poet Francis Quarles rated darkness alongside silence as an aid to internal reflection:

Let the end of thy first sleep raise thee from thy repose: then hath thy body the best temper, then hath thy soule the least incumbrance; then no noise shall disturbe thine ear; no object shall divert thine eye.

My own night-waking confirms this difference between night- and day‑waking; my night brain definitely feels more dreamlike. When dreaming, our minds create imagery from memories, hopes and fears. And in the dead of night, drowsy brains can conjure up new ideas from the debris of dreams and apply them to our creative pursuits. In the essay ‘Sleep We Have Lost’ (2001), Ekirch wrote that many had probably been immersed in dreams moments before waking up from the first of the two sleeps, ‘thereby affording fresh visions to absorb before returning to unconsciousness. Unless distracted by noise, sickness, or some other discomfort, their mood was probably relaxed and their concentration complete’.

Ekirch’s ideas about segmented sleep derive from old documents and archives, but are supported by modern research. The psychiatrist Thomas Wehr of the US National Institute of Mental Health found that segmented sleep returns when artificial light disappears. During a month-long experiment in the 1990s, Wehr’s subjects had access to light for 10 hours per day, as opposed to the artificially extended period of 16 hours that is now the norm. Within this natural cycle, Wehr reported, ‘sleep episodes expanded and usually divided into two symmetrical bouts, several hours in duration, with a one- to three-hour waking interval between them’.

Both Ekirch and Wehr’s work continue to inform sleep research. Ekirch’s ideas were the subject of a dedicated session at Sleep 2013, the annual meeting of the US Associated Professional Sleep Societies. One of the biggest implications to emerge was that the most common insomnia, ‘middle-of-the-night insomnia’, is not a disorder but rather a harking back to a natural form of sleep – a shift in perception that greatly reduced my own concern about night-waking.

It is 7.04am. I have been writing for nearly three hours and I now am going back to bed for my second sleep. I will work again later in the day. It is only because of the way that I have made my life (no children, self-employed) that I can be a segmented sleeper.

But I have also had to fit my sleeping habits into periods of nine-to-five work, and the two are hardly compatible; few sounds are more dreadful than the buzz of an alarm when you have spent several hours in the night awake and have only just gone back to sleep. It is the clash between ‘natural’ sleep patterns and our rigid social structures – clock-time, industrialisation, school hours, working hours – that makes segmented sleeping seem like a disorder and not a boon.

Creative people often find ways to live without the nine-to-five, either because they are successful enough with their books, art or music that they don’t need a day job, or because they seek employment that allows a flexible schedule, such as freelancing.

In Daily Rituals: How Artists Work (2013), Mason Currey describes the routines of famous writers and artists, many of whom are early risers, and several segmented sleepers. Currey found that many hit on the pattern of segmented sleep by accident. The architect Frank Lloyd Wright, for instance, would wake around 4am, unable to fall back to sleep – so he would work for three or four hours, then take a nap. The Nobel Prize-winning novelist Knut Hamsun would often wake after sleeping for a couple of hours. So he kept a pencil and paper by his bed, and would, he said: ‘start writing immediately in the dark if I feel something is streaming through me.’ The psychologist B F Skinner kept a clipboard, paper and pencil by his bed to work during periods of night wakefulness, and the author Marilynne Robinson regularly woke to read or write during what she called her ‘benevolent insomnia’.

Some of us are morning people, others night people – early birds or night owls. Currey says that creative people who work in the night are ‘drawing on an optimal state of mind for their work’, governed by personal natural rhythms, rather than choice.

The novelist Nicholson Baker was the only person Currey encountered who had consciously decided to practise segmented sleeping. Baker is very aware of his own writing habits and routines, and likes to experiment with new writing rituals for each new book, Currey told me, so it seems appropriate that he would carve out extra productive hours by creating two mornings in one day.

Indeed, when Baker was writing what would become A Box of Matches (2003), a novel about a writer who gets up around 4am, lights a fire and writes while his family sleeps, Baker himself practised this ritual, then went back to bed for a second sleep.

‘I found that starting and nurturing this tiny early flame helped me to concentrate,’ Baker told The Paris Review. ‘There’s something simple and pleasantly meditative about building a fire at four in the morning. I started writing disconnected passages, and the writing came easily.’

It is this dreamy flow that seems to characterise creative work undertaken in the middle of the night. Between sleeps, there is the stillness, the lack of distraction and perhaps a stronger connection to our dreams.

Blissfully zonked out by prolactin, our night brains allow ideas to emerge and intertwine as they might in a dream

Night also triggers hormonal changes in our brains that suit creativity. Wehr has noted that, during night-waking, the pituitary gland excretes high levels of prolactin. This is the hormone associated with sensations of peace and with the dreamlike hallucinations we sometimes experience as we fall asleep, or upon waking. It is produced when we feel sexual satisfaction, when nursing mothers lactate, and it causes hens to sit on their eggs for long periods. It alters our state of mind.

Prolactin levels are known to increase during sleep, but Wehr found that (along with melatonin and cortisol) it continues to be produced during periods of ‘quiet wakefulness’ between sleeps, triggered by the natural cycles of light and dark, not tied to sleep per se. Blissfully zonked out by prolactin, our night brains allow ideas to emerge and intertwine as they might in a dream.

Wehr suggests that not only have modern routines altered our sleeping patterns, they have also robbed us of this ancient connection between our dreams and waking life, and ‘might provide a physiological explanation for the observation that modern humans seem to have lost touch with the wellspring of myths and fantasies’.

Ekirch agrees: ‘By turning night into day, modern technology has obstructed our oldest avenue to the human psyche, making us, to invoke the words of the 17th-century English playwright Thomas Middleton, “disannulled of our first sleep, and cheated of our dreams and fantasies”.’

Modern technology might have muddied the channels that connect us to our dreams and encouraged routines that are out of synch with our natural patterns, yet it can also lead us back. The industrial revolution flooded us with light, but the digital revolution might turn out to be far more sympathetic to the segmented sleeper.

Technology fuels the invention of new ways of organising our time. Home working, freelancing and flexitime are increasingly common, as are concepts such as the digital nomad and the online or remote worker – all of whom might adopt a less rigid routine, one that allows night-wakers to find a more harmonious balance between segmented sleeping and work commitments. If we can make time to wake in the night and ruminate with our prolactin-sloshed brains, we may also reconnect to the creativity and fantasies our forebears enjoyed when, as Ekirch notes, they ‘stirred from their first sleep to ponder a kaleidoscope of partially crystallised images, slightly blurred but otherwise vivid tableaus born of their dreams’.