You press the pedal at the base of Eduard Bersudsky’s sculpture Piper (2013). The shadow on the wall moves, the cogs begin to hum, the little bell rings, and the pair of gendered fauns flex their legs to activate the dog typist at the typewriter hammering out memos lost to history. Tip, tap, tippity-tap, its tail sways, and the muscular fauns leer. They have wolves’ heads, just as the humanoid pair animating the giant buggy face is monkey-headed. They make the face smile, his eyes move this way and that, and his pipe — crikey, there’s a bird in his pipe! — go up and down. And are those tiny feline-ursine centurions armed with shields guarding the Piper, and what are they guarding it from? Unless, of course, this is a Jungian dream of the unconscious where beasts and innocents are deliciously free to copulate, poke fun at authority, snack on bugs, and squeak instead of talk?

But these are rhetorical questions, because what matters here is the depth of your feeling. Faced by Bersudsky’s work, you’re stabbed with sorrow at the futility of the human endeavour and yet waves of belly laughter ripple through you. This magical spectacle seems, without words, to be telling you something essential, and you can’t stop pressing the pedal.

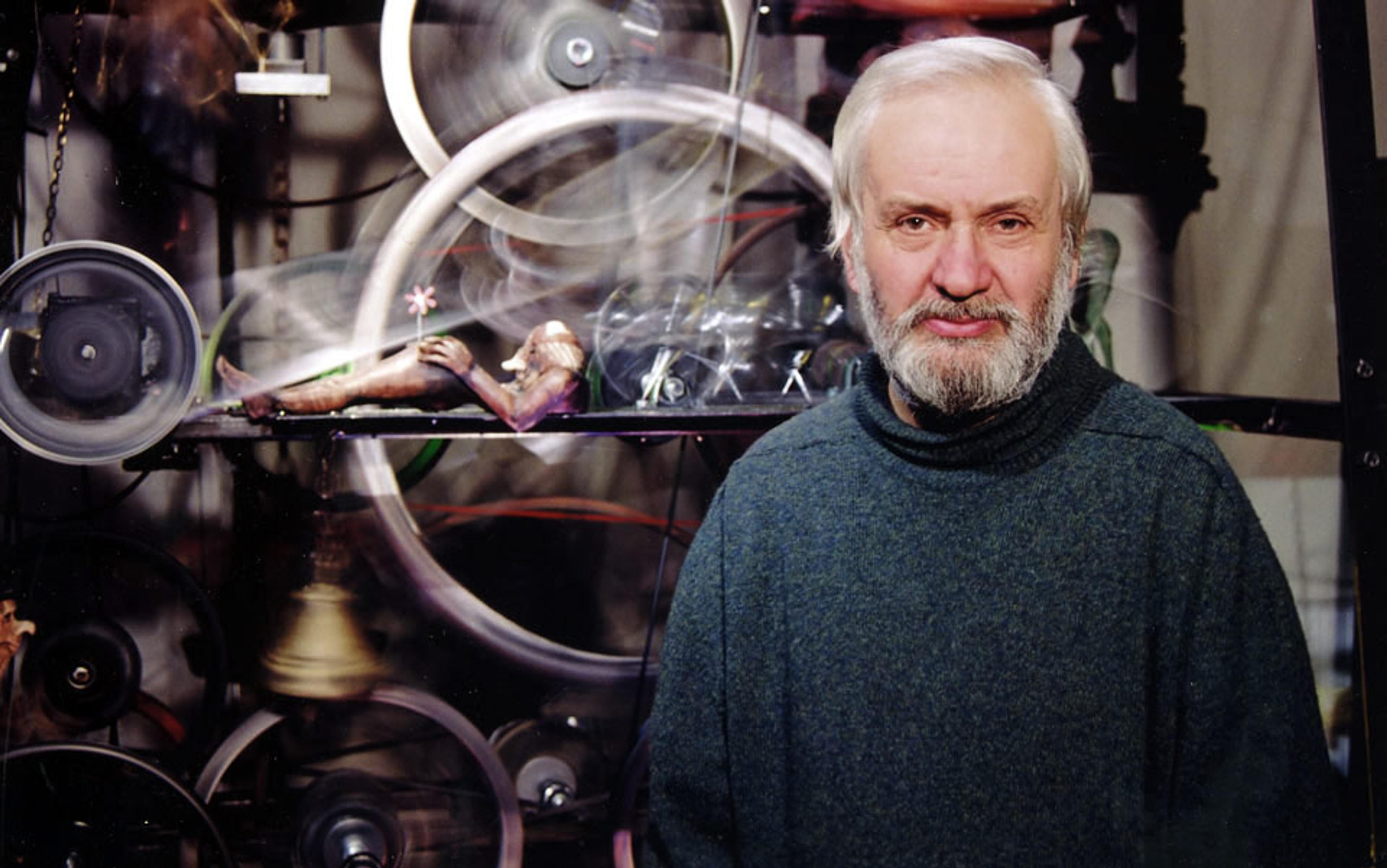

It helps that you are standing inside a Gothic church deep in the Scottish Highlands, and that the church is Kilmorack Gallery — a secular shrine to the sublime, where art is God. But Bersudsky, the artist who painstakingly carved these figures and, like a magician-alchemist, animated them with a hidden mechanism, doesn’t care for such big words as God, Politics, History, or even Art. In fact, he doesn’t much care for words, full stop. Once, he stopped speaking for two years. Why? He shrugs. Some things need no explaining, and anyway, he was too busy carving fallen trees into lifelike animals for the park department of what was then called Leningrad. In those days in the 1970s, it was the only paid job in the Soviet Union available to a nonconformist artist branded an ‘enemy’ by a regime that was no one’s friend.

Bursting with creative energy, the young Bersudsky carved animals for children’s playgrounds in the daytime, and worked through the night in his 12 square-metre bedroom in a communal flat. He spent his mute Soviet years building his first kinemats or kinetic sculptures, from odd bits and pieces: electrical plugs, the wheels of Singer sewing machines, factory motors he’d swap for a bottle of vodka. Blending the refuse of Soviet life with his crafted creatures, he constructed his own poetry of the absurd to straddle fantasy and satire, the lyrical and the grotesque. And because these kinemats were ideologically and aesthetically wrong until perestroika came along, only a close circle of friends and aficionados saw Bersudsky’s Hieronymus Bosch-like creations — works such as Self-Portrait With a Monkey (2002).

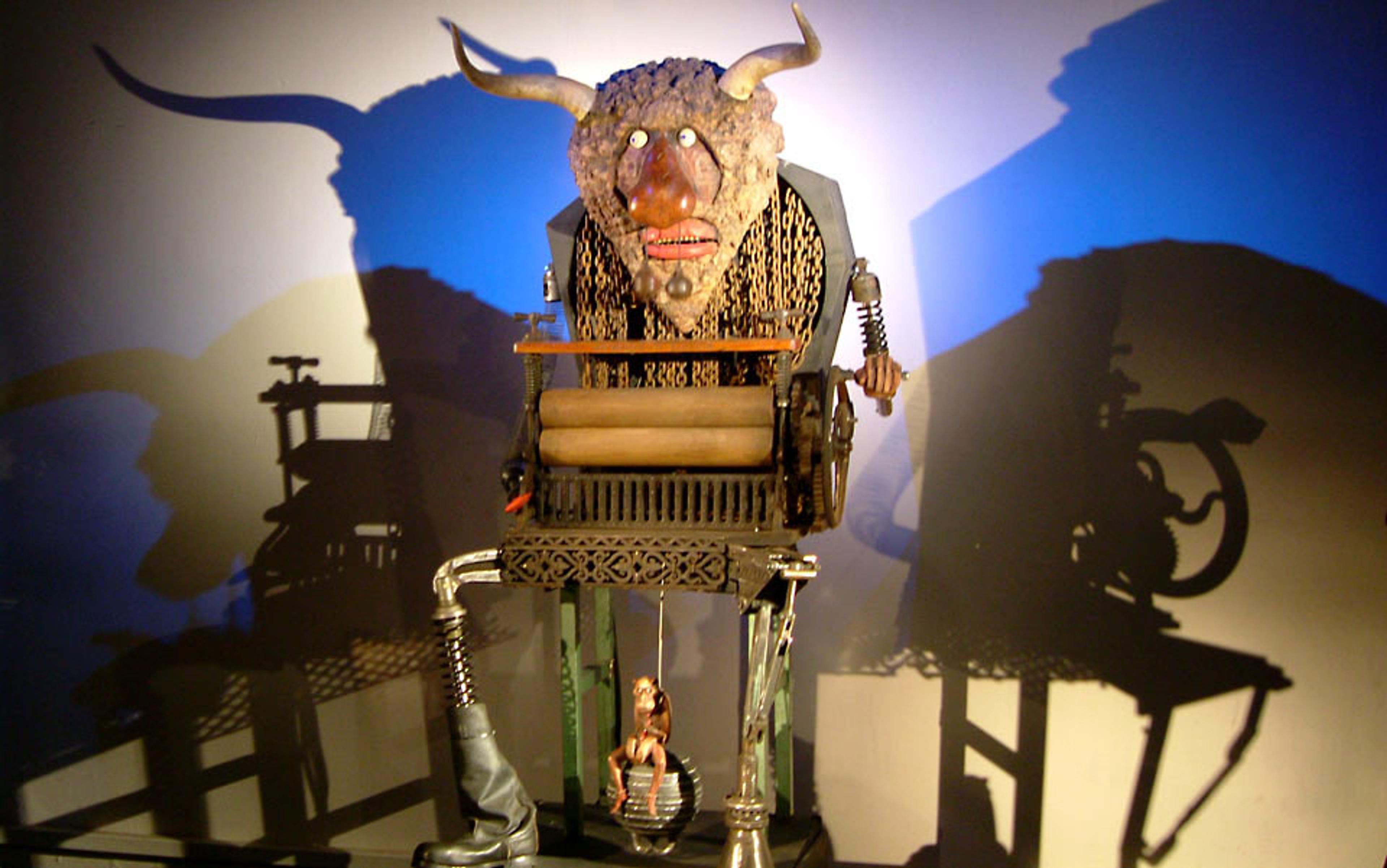

Bersudsky’s wife and collaborator Tatyana Jakovskaya switches it on for me at the couple’s Glasgow home and workplace, the Kinetic Theatre Sharmanka. A monkey hangs by the neck from a chain attached to the testicles of a mechanical giant with a horned head. When the light comes on, the giant turns into an organ-grinder, tapping along with a prosthetic army-booted foot to the Russian song ‘Separation’. ‘Farewell, my homeland, my beloved,’ sings the bass voice, recorded by a friend of the couple who was forced into political exile in the 1970s. Just as the ever-morphing monkey-man and monkey-woman are mascots of subversion in his work, so the organ grinder is emblematic of the cyclical Bersudskian universe. It crops up in his disturbing early drawings, as well as in his later works. And it gives Sharmanka its name, which is a wink at the barrel-organ’s arrival in Russia with the popular tune ‘Charmante Catherine’.

I wonder whether the incessant banal chatter of the world drives a wedge between the sane private self and the strident public self

On and on the organ grinds, friendly yet sinister, childish yet sorrowful, repeating an expired tune of hope to a ghostly audience. This tongueless tune lodges in your psyche like an existential drip of futility and persistence: the musical equivalent of Samuel Beckett’s line ‘I can’t go on, I’ll go on.’ The genius of Bersudsky’s world is to tell nothing yet reveal all, through recurring dreamlike objects like the organ grinder, the little person’s only weapon against a power-mad world.

Carried along by this funny-sad shadow play into a state of hypnosis, I’m reminded of the Argentine-born writer Alberto Manguel’s words: ‘True experience and true art… have this in common: they are always greater than our comprehension, even than our capabilities of comprehension.’ But there is one thing I do comprehend.

We are all sad children who have forgotten how to play. We are hanging on to the broken merry-go-round of history where failure and injustice stalk us. The circus of tyranny goes round and round, and the cultural currency — be it advertising slogans, political fashions, or the diamond skull of corporate art — belongs to the powerful of the day, blithely unaware that tomorrow they too will be bug-eyed exhibits in the Museum of Broken Things.

No wonder Bersudsky is mistrustful of language and speaks through his carvings and cogs. He is already making, from the scraps of today, the kinemat of tomorrow. He can’t stop making, whether snowbound in Leningrad or in spring-blossomed Glasgow. In his back room workshop, the viscera of modernity is filed in drawers and labelled: ‘springs’, ‘bells’, ‘clocks’. His work in progress is a flock of birds that buzz around a…a sort of … It chokes me up. I can’t describe it.

What are you working on? I ask Eduard. Oh, just something to keep me amused. He adds, in Russian: ‘A child who plays doesn’t cry.’ And he shuffles off to make tea with sliced lemon. With her decades of experience as theatre director, Tatyana will be the one who breathes light and music into his work, together with the help of her son, Sergey Jakovsky. He was still a boy when they emigrated to Scotland 20 years ago.

The couple are indifferent to their surroundings, their material needs so simple that they leave their theatre home only when they run out of food or need to travel for a show. They inhabit a parallel dimension, and I would like to live there with them.

‘To create an alternative world — that is the artist’s true happiness,’ Tatyana says as Eduard spoons half a jar of honey into my tea. ‘Not money. We are rich because we do something we love.’

Eduard and Tatyana are the embodiment of a rare thing: the unity of life and art. Their life, like their art, is a form of humanist resistance as well as an act of love, in the spiritual sense of the word. There is precedent: the two of them remind me of another subversive cult couple with a lasting legacy, the ‘Bonnie and Clyde of art’, Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely, makers of fantastical sculptures. For de Saint Phalle, play was art, and so she played ‘furiously’. For Tinguely, ‘le rêve est tout’, the dream was everything. They married in 1971 but had no children together. Instead, their fertile artistic coupling lasted for the best part of the last half-century. After Tinguely’s death in 1991, Bersudsky received the gift of his Parvalux electrical motors and they found their way into the next kinemats.

‘If you want to work on your art, work on your life,’ Anton Chekhov once said. Meeting Eduard and Tatyana forces me to ask whether, for most of us living in this age of sound and fury and Twitter, there isn’t in fact a neurotic chasm between the two. And taking this further, I wonder whether the incessant banal chatter of the world drives a wedge between the sane private self and the strident public self. I think it does, I can hear it in my head. Tip, tap, tippity-tap, all those memos lost to history.

When I’m writing, dancing, learning to play the accordion, fooling around with the dog, or making a salad — all forms of play — I’m happily entranced. I can’t lie or be lied to when I’m at the source of creation. When I’m out in the world, virtually or literally, my ego fanned out in desperation like a peacock in mating season, I am distracted by the glitter of worldly promise. This is when the rot of adult delusion sets in. It’s a form of insanity.

How to avoid this fracture of the integral self? How to stop ourselves surrendering to the cynicism of a corrupt world, with its self-trumpeting dictators, maniacs disguised as gurus, and con men with fortunes and painted clown’s smiles? Meeting Eduard and Tatyana has shown me one way: if you have an inner sanctuary, you have less need to make spectacular outings in your emperor’s new clothes.

The creative genius of Eduard Bersudsky and Tatyana Jakovskaya is incidental to their life philosophy; in other words, there is hope for all of us. In fact, to seek a realm of freedom and truth within is perhaps the only meaningful task in our lives.

To see Piper in action is to be reminded of what we are: orphaned children whose only path home is to remember how to play and dream again.

Go on, press the pedal again. Nobody’s looking.