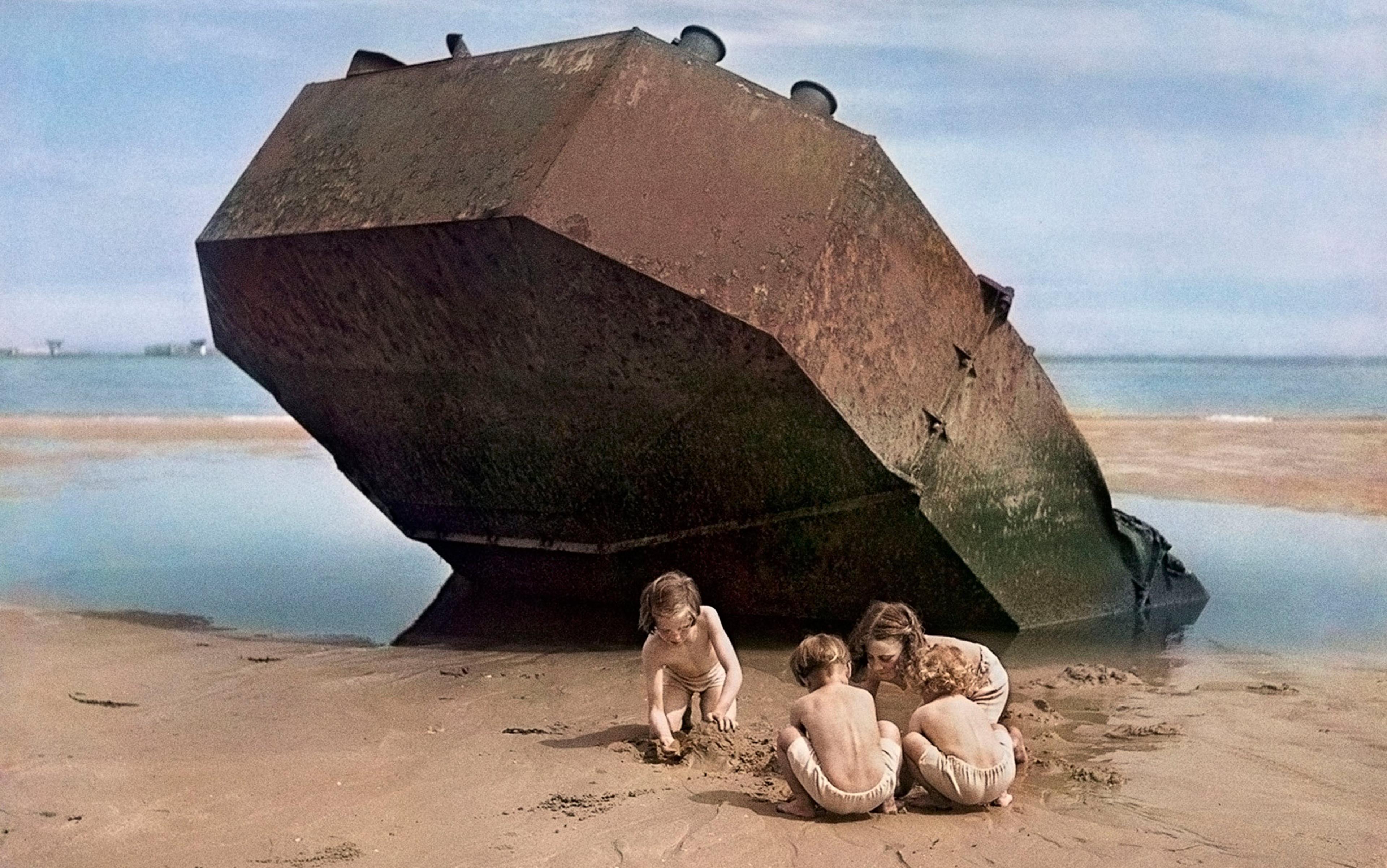

On 25 March 1965, the planes out of Montgomery, Alabama were delayed. Thousands waited in the terminal, exhausted and impassioned by the march they had undertaken from Selma in demand of equal rights for Black people. Their leader, Martin Luther King, Jr, waited with them. He later reflected upon what he’d witnessed in that airport in Alabama:

As I stood with them and saw white and Negro, nuns and priests, ministers and rabbis, labor organizers, lawyers, doctors, housemaids and shopworkers brimming with vitality and enjoying a rare comradeship, I knew I was seeing a microcosm of the mankind of the future in this moment of luminous and genuine brotherhood.

In the faces of the exhausted marchers, King saw the hope that sustained their hard work against the violence and cruelty that they had faced. It is worth asking: why was King moved to try to create a better world? And what sustained his hope?

A clue can be found in the PhD dissertation he wrote at Boston University Divinity School in 1955:

Only a personal being can be good … Goodness in the true sense of the word is an attribute of personality.

The same is true of love. Outside of personality loves loses its meaning …

What we love deeply is persons – we love concrete objects, persistent realities, not mere interactions. A process may generate love, but the love is directed primarily not toward the process, but toward the continuing persons who generate that process.

King subordinates everything to the flourishing of human persons because goodness in this world has no home other than that of persons. Their wellbeing is what makes the events of our lives and of our collective history worthy of effort and care. In order to demonstrate that we are worth the struggle within and among ourselves, King sought to find love between the races and classes on the basis of philosophical claims about personhood. A decade after his dissertation, he was at the forefront of the Civil Rights movement, marching to Montgomery.

Can we still grasp and live the hope that King found? Capitalism, imperialism, nationalism, racism – like iron filings near a magnet, all these historical forces seem to be pulled together today into one fatal, immiserating direction. They teach us hateful ways to behave and promote heinous vices such as pride and greed. Desires flee beyond prudent limits and rush toward disaster. It seems we are not worth all that we used to think we are worth. Can we replace our narcissism with a virtuous self-regard? The philosophical tradition of personalism tells us that we can and do have hope for our future.

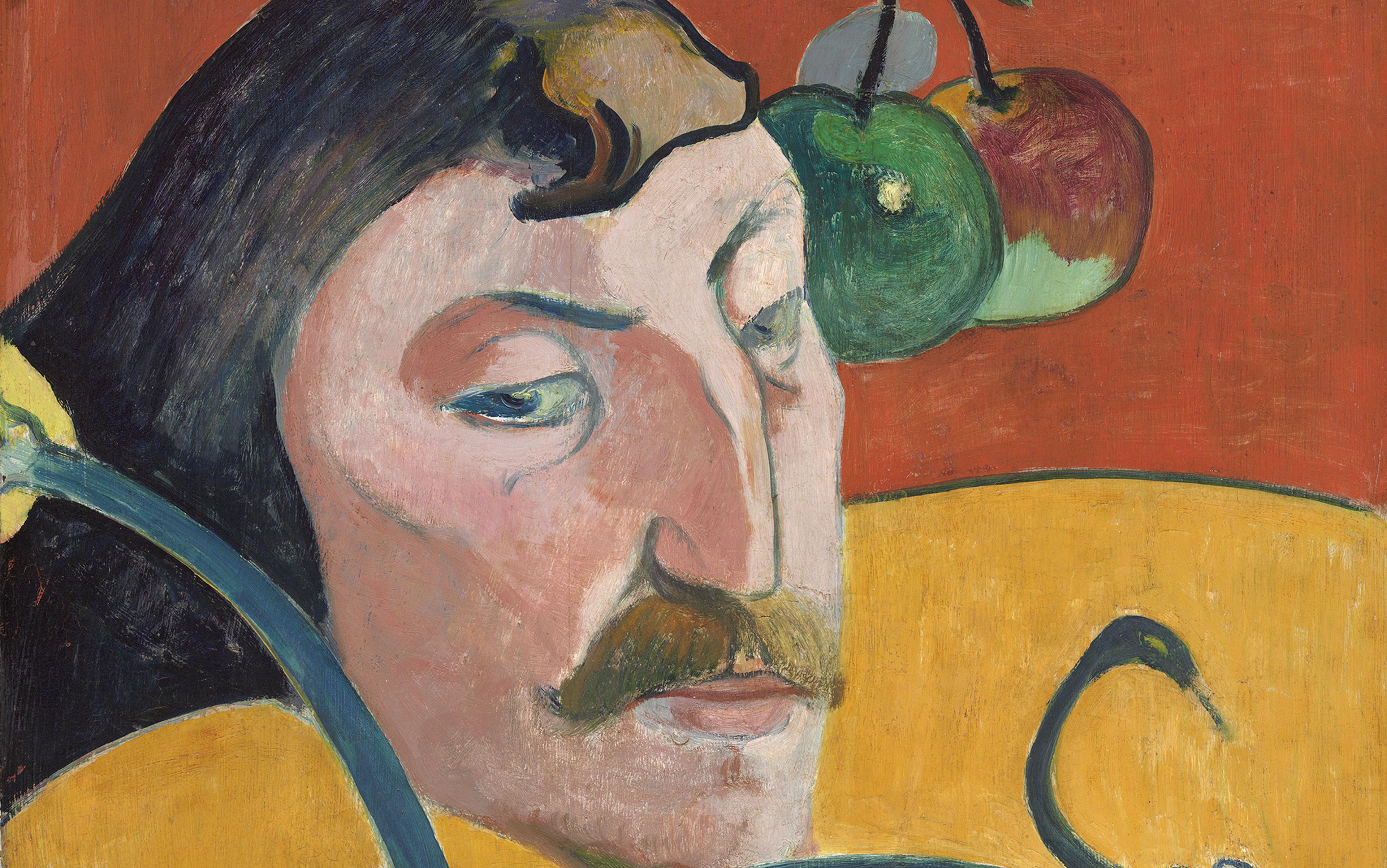

King’s hope came from his understanding of Christianity through the philosophy of personalism. He largely acquired this line of thought during his graduate studies at Boston. His advisors in Divinity School had been students of Borden Parker Bowne (1847-1910), the first philosophy professor at Boston University. Bowne founded Boston personalism, which, with William James’s pragmatism, was one of the two earliest American schools of philosophy. For Bowne, personhood is not the bundles of characteristics we call ‘personality’. Instead, it is the intelligence that makes reality coherent and meaningful. The core of his thought is that personhood is ‘the deepest thing in existence … [with] intellect as the concrete realisation and source’ of being and causality.

Bowne says that if we dismiss abstractions because they are static and have no force in the world, what is left is solely the ‘power of action’. Action for Bowne is intelligence understood as a force that activates the concrete reality of things. This reality is not static substance but the ceaseless business of the effect that entities have on other entities. Personhood is the non-material and non-biological power of relations among things, which activates all the processes of the world. Reality itself is thus deeply personal. Without personhood, it would be atomised and inactive – and therefore unintelligible. In Bowne’s view, only the concept of intelligent selves is adequate for explaining how things are constituted and inter-related. Being is nothing without causality; causality is nothing without intelligence. Reality is nothing without idea; idea is nothing without reality. This intimate connection of mind and the world means that nothing can be understood apart from the intelligence that perceives and understands it, replacing inert substances with the ever-flowing labours of our human need to find meaning in life as we encounter it.

Personalism always begins its analysis of reality with the person at the centre of consciousness

Bowne’s ideas had many predecessors, from Latin Christianity through Immanuel Kant, using many different theories and concepts, about what a human being is and about the personhood of God in its relation to our own personhood. His forceful argumentation influenced James, who helped found the American philosophical tradition of pragmatism shortly after Bowne’s first books were published and who drew increasingly close to personalism, as did the idealist philosopher Josiah Royce. Bowne was at the centre of this troika of canonical American philosophers at the turn of the 20th century. His teaching rippled out through personalist philosophers on the West Coast and through his students at Boston, notably Edgar S Brightman and Harold DeWulf, both of whom later became teachers of King.

Many other forms of personalism had been developed in Europe in the previous century: theistic and non-theistic, socialist or communitarian and libertarian, abstractly metaphysical and concretely ethical. It is more an approach to thinking than a method, doctrine or school. Personalism always begins its analysis of reality with the person at the centre of consciousness, to which it attaches the most profound worth. Some versions develop this through ontology or metaphysics; some, through theologies associated with most denominations of the Abrahamic religions; and some, through the intersubjective and communitarian nature of human life. My own version makes the structure of moral meaningfulness the first step and first philosophy, as I will explain below. All versions seek an integrated, ethically strong comprehension of personhood as the heart of the life of humankind.

Though personalism continues to be a field of robust philosophical research, in American academic philosophy after the Second World War it faded under the hegemony of analytic philosophy. But in King’s hands it became forceful as a practice for justice and other moral ends. Its resources have not been exhausted. Careful revision and updating can make it a source of illumination and hope in the circumstances we face a half-century after King.

Why should we update personalism, and what useful purpose will this serve? Our ideas about the nature of human beings are today undergoing a severe challenge by the new philosophies of transhumanism. Through personalism, we can understand and appreciate our purposes and obligations, as well as the dangers posed by transhumanism.

The best known of these transhumanist philosophies is effective altruism (EA). The Centre for Effective Altruism was founded at the University of Oxford in 2012 by Toby Ord and William MacAskill; largely inspired by Peter Singer’s utilitarianism, EA has been an influential movement of our time. As MacAskill defines it in Doing Good Better (2015):

Effective altruism is about asking, ‘How can I make the biggest difference I can?’ And using evidence and careful reasoning to try to find an answer. It takes a scientific approach to doing good.

This is not as clear cut as it might seem, and it has often led to the uncomfortable conclusion that the accumulation of capital by the wealthy is morally necessary in order to affect the world for the better in the future, largely regardless of the consequences for living persons. Its proponents argue that society does not sufficiently plan for the distant future and fails to store up the wealth that our successors will need to solve social and existential challenges.

Other transhumanist theories include longtermism, the idea that we have a moral obligation to provide for the flourishing of successor bioforms and machinic entities in the very distant future, at times regardless of consequences for those now living and their proximate next generations. There is also a kind of rationalism that justifies the moral calculations on which provision for the future instead of for the living is based; cosmism, the vision for exploration and colonisation of other worlds; and transhumanism, which aspires to assemble technologies for the evolution of humankind into successor species or for our replacement by other entities as an inevitable and thereby moral duty. All of these, including the various versions, are sometimes named by the acronym TESCREAL (transhumanism, extropianism, singularitarianism, cosmism, rationalism, effective altruism, longtermism). Here I refer to these as ‘transhumanism’.

The core argument common to these lines of thinking, according to the philosopher Émile Torres writing in 2021, is that:

[W]hen one takes the cosmic view, it becomes clear that our civilisation could persist for an incredibly long time and there could come to be an unfathomably large number of people in the future. Longtermists thus reason that the far future could contain way more value than exists today, or has existed so far in human history, which stretches back some 300,000 years.

From this point of view, human suffering today matters little by the numbers. Nuclear war, environmental collapse, injustice and oppression, tyranny, and oppression by intelligent technology are mere ripples on the surface of the ocean of history.

This idea of the agency of the inorganic is one of the key arguments for decentring the human

Each element of these transhumanist ideologies regards human personhood as a thing that is expiring and therefore to be replaced. As the longtermist Richard Sutton told the World Artificial Intelligence Conference in 2023: ‘it behooves us [humans] … to bow out … We should not resist succession.’ Their proponents argue for the factual truth of their predictions as a way to try to ensure the realisations of their prophecies. According to the theorist Eliezer Yudkowsky, by ‘internalising the lessons of probability theory’ to become ‘perfect Bayesians’, we will have ‘reason in the face of uncertainty’. Such calculations will open a ‘vastly greater space of possibilities than does the term “Homo sapiens”.’

A personalist approach deflates these transhumanist claims. As the historian of science Jessica Riskin has argued, a close examination of the science of artificial intelligence demonstrates that the only intelligence in machines is what people put into them. It is really a sleight-of-hand; there is always a human behind the curtain turning the wizard wheels. As she put it in The New York Review of Books in 2023:

Turing’s literary dialogues seem to me to indicate what’s wrong with Turing’s science as an approach to intelligence. They suggest that an authentic humanlike intelligence resides in personhood, in an interlocutor within, not just the superficial appearance of an interlocutor without; that intelligence is a feature of the world and not a figment of the imagination.

Longtermists’ notions of future entities lack everything we know about conscious intelligence because they use consciousness or living beings as empty black-box words into which even meaningless notions will fit. Effective altruists dismiss the worth attributable to every human, squashing it by calculations that cannot prescribe moral value, whatever these proponents claim. As we can see in the theories of longtermists such as Nick Bostrom and effective altruists such as Sam Bankman-Fried, instead of working with human ethical values, they work with numerical values, ignoring the massive body of thought from anthropologists such as Webb Keane and from phenomenologists such as Rasmus Dyring, Cheryl Mattingly and Thomas Wentzer showing that values are neither empirical nor quantifiable but nonetheless real forces in human affairs. Transhumanism as a whole assigns agency to alien beings and electronic entities that do not exist – and perhaps are inconceivable.

This idea of the agency of the inorganic is one of the key arguments for decentring the human. Consider, for example, salt. Salt affords certain effects in certain conditions: it produces a specific taste, it corrodes other materials, it serves certain functions in organisms. But it is humans who organise these events under the concept of causality. What salt does, it does without consciousness. Consciousness neither starts nor halts its effects, broadly speaking. What sense is there, then, in saying that salt has agency when it is more illuminating to say that it is a cause of effects under some conditions?

In ordinary language, we frequently speak of machinery or ideas ‘doing’ things in our lives. But they do nothing. People – human persons – produce, operate and apply their creations. The problem with assigning agency, even informally, to the nonhuman is that this disguises the strength of human control, limited though it is in other respects. It leaves us unaware when a more toxic and cunning human drives to take control because we are busy trying to control the world rather than ourselves. Although some people think that machines or ideas are in control of them, it is really other humans. If we overlook this truth, we accept an untruth – an untruth that condemns us to the mercy of our worst drives and behaviours. When we devalue humanity, we unleash our self-destructive drives, thereby turning reason into destructive irrationality. In this way, we are in fact governed by our own human drive for self-destruction.

This drive seems to differentiate us from other animals as much as language or historicity do. If we provoke this drive too much, we shall have nowhere else to turn in our struggle to flourish in the natural world. We must, instead, search out our integrity and worth because the alternative is despair.

The great and encompassing thing that humans create is our story: human history, the sum of our behaviour and our deeds. We create it with and amid the world around us out of our need to make sense of the world. This need, which builds our moral life, is part of what drives everything we do. It drives the ways we pursue survival, for, without a sense of meaning, we have little will to survive. The pursuit of survival can lead us to meaningfulness but, if it fails to do so, the pursuit itself ceases. We guide ourselves by the stories we choose, for storytelling inhabits all ways of knowing and acting. If the meaning we seek as human persons is overtaken by the story that our self-destructive drive presents in the form of transhumanism, we shall not survive.

Persons are worth more than even justice and goodness are, because it is for the sake of persons that we fight for justice and goodness. In the face of possible profound changes, it often seems we must choose between being good and just to ourselves, and being good and just toward nature. The possibility of these radical changes legitimately requires that we profoundly deflate our anthropocentrism, since overblown self-regard has served us poorly. But how do we do this while encouraging our fraught capabilities and appreciating the worth of our flawed species?

The kind of personalism that I have developed out of Bowne’s ideas as a response to this and other questions I call moral agency personalism. Moral agency is the activity of judging and choosing between good and evil, right and wrong, justice and injustice. In my view, every thing that has such moral agency is a person, and all persons are moral agents. (The evidence that some nonhuman species make moral choices, sometimes based on memory and history, has been accumulating.) Adding this possibility to personalism formally recognises worth in all persons, nonhuman as well as human. As a belief and a practice, it can ground a virtuous, as opposed to vicious, self-regard that human and nonhuman persons can exercise for themselves and for other persons. This kind of self-regard is distinct from self-importance.

We can develop a moral agency personalism that has some of the resources we need in facing the human future. We can find these by altering some fundamental concepts of personalism. These updates include: accepting the fact of nonhuman moral agents or persons; including the body in our understanding of individual lives and of interpersonal relations; and rethinking the idealist ontology in personalism in order to make it an ethics-as-first-philosophy approach, with less emphasis on ontology. The guiding idea of these changes is that, in making moral sense out of experience, personal moral agency enlarges our relations to the whole range of our lives and our care for all beings.

We need to respect ourselves as persons with the power to decide not to continue to harm

Personalism gives us robust resources for identifying our worth and for believing in it. It can encourage us to enhance our worth by our acts in seeking goodness, compassion and justice, and guide us to the richest possible moral life. Because our personhood is the home base of our point of view, there is no way forward other than to maintain our integrity while learning what we must in order to thrive.

The initial and most basic of these resources we should tap is the strength not to do more harm. We are the ones who deploy transhumanist projects into the only world that sustains us. We are the ones degrading the environment. And we are the only ones who can stop us from doing both. For this, we need to respect ourselves as persons with the power to decide not to continue to harm. This is the minimum we must do.

Respecting the moral worth of persons also ignites our capacity to care for others. We respond with aid to calls for help when we learn to recognise moral obligation pertaining to every person, including ourselves, and toward every other person. Furthermore, our humanitarian disposition is frequently a sure way to developing sympathy for the natural world and the life within it.

Understanding our personal moral agency enables a wise combination of the two general forces of moral action: power and compassion. Power is the logic by which we carry ideas and lines of thought to fulfilment in activity. Compassion is the potentially unbounded lovingkindness with which we temper power and extend love to widening spheres in our lives. So far as we know, we are the only living beings who can use these forces in moral decision-making. But even if other beings have moral personhood, nothing of the sort relieves us of the moral obligation that our possession of these two capabilities makes it possible to accept and to follow.

We possess our history, just as we make it – another resource that is unique to us, so far as we know. History is the engine of self-awareness. As the substance of all that we have done and the actual conditions for the possibility of all that is and will be, historical consciousness serves us as the indispensable locus of reflection and deliberation. No unchanging and antiquated images of ourselves restrain our understanding of history because we create the past anew whenever we study it and reflect on it. It is therefore the great endowment for a renewed humanistic extension of personhood to all humankind and to all life.

There are two more resources, pointing to opposite ends of the spectrum of our concerns. The first is that the personalist grasp of what we are worth supports democracy. Democracy has depended on a powerful conception of personal agency and responsibility that cultural and political changes now challenge, in addition to the material issues of human life in the Anthropocene era. These social and natural developments closely reflect each other. Learning to live together is the worthy goal of democracy. But if we are to pursue concord and peace by that road, we must value ourselves, accept our moral nature with its obligations, submit our desires to what the moral worth of every living being requires of us, and work in response to present and patent human suffering and real human joy.

At the opposite end, on the cosmic scale, lies another possibility for virtuous human self-regard afforded us by personalism. Simply put, it is this: it might become clear to us that the universe is constitutively pervaded by consciousness, or is conscious in all its parts, or is inside of a super-consciousness. These are versions of the notion of cosmic consciousness called panpsychism. Panpsychism is not just about what we can know or do but about reality itself. This appeals to those who have for a moment felt the life of the universe in a small experience and do not want to dismiss what that feeling says and means to them just because it is not empirically verifiable. In our best moments, our lives feel epiphanous.

The moral agency of persons thrives when agents act in obligation to their individual and collective selves

At the same time, however, panpsychism can conflict with the empiricism that is so valuable because it is used to make things that work well for us. And yet other kinds of things, such as erotic love and spirituality, also work well for us and are not conducive to the usual demands of empiricism. For now, it is easy to think that a universal consciousness makes our consciousness unimportant, but there might be ways of getting the opposite outcome. Current advances in physics and biology are starting to support the belief that our consciousness affects reality by working with reality as a consciousness that includes ours. That is, our observing and predicting are inside, not outside, the phenomena we encounter. We are not the crown jewels of creation, but our self-referentiality, our critical awareness and our moral lives form personhood as an important part of a universe that is thereby less alien and cold.

If a suitable form of panpsychism is true, human personhood means more to reality than is usually thought. This kind of personalism puts us into a community or, rather, into many communities made up of conscious beings capable of moral responsibility. The moral agency of persons thrives when agents reflectively act in obligation to their individual and collective selves rather than in seeing themselves through the needs of imagined others in the undetermined future.

What King observed in Montgomery airport in 1965 was actual persons developing their moral purchase with each other. He saw this as the processes of goodness and love at work in their proper sphere: our common existence. King wanted us not only to recognise the unique and infinite value of every person, but to understand it so powerfully that we would feel ourselves obliged to take the action that this recognition requires. As he wrote, we need only look around us at the struggles for a decent and free life that others wage to sense the profundity of human worth and to see that we all depend on one another. That this has the power to inspire us to fight for change sustained his hopes.

We face an urgent present choice. We might prefer that algorithms or despots act for us because our own power of judgment is too explosive to manage. That would suit the purposes of infomaniacal hypercapitalism, which seeks to control consumers rather than to enrich persons. But turning over our judgment to machines does not lock away our power to destroy ourselves and others. We must govern ourselves even as we evolve. This requires an enduring connection to our humanity and a willingness to work hard with one another. This can be successful only if and when we hold fast to all that we are.