People get stoned in cars. People get fried at home before driving off on epic quests for gas‑station goodies. Because marijuana smells and frequently induces paranoia, users – especially young ones with potentially prying parents – often like to smoke in seclusion. Where I grew up, that meant escaping the post-industrial wasteland of town for gravel roads among outlying corn and soybean fields, where Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band could be played at full tilt without once thinking of uninvited others. End result: teenagers, ripped out of their minds, flying down backcountry highways on the return trip, floating on thoughts of skies with diamonds.

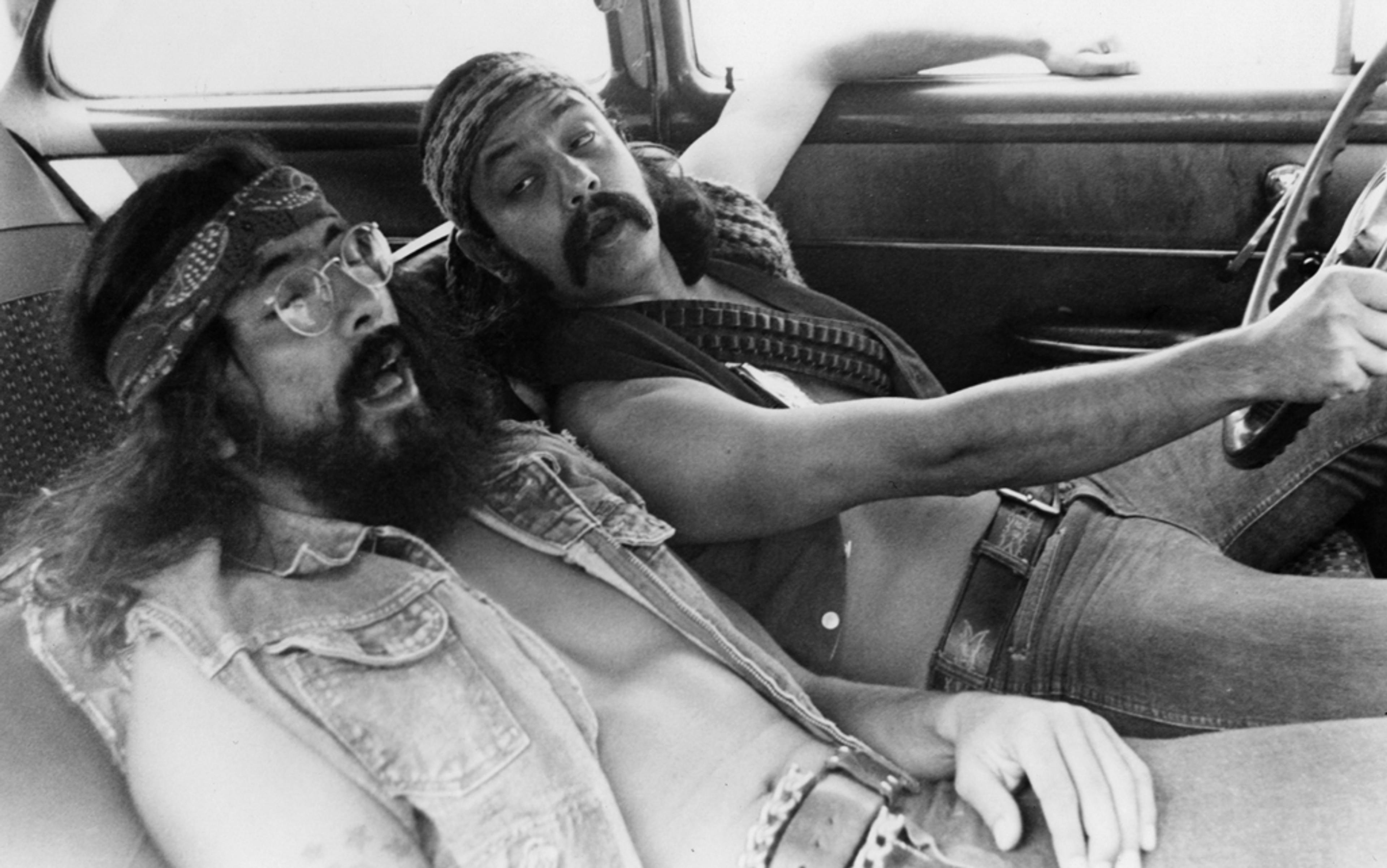

We know all this. It’s the stuff of endless pop‑culture tropes, internet memes and insider film references. Indeed, few stoner movies don’t address the car issue. For sure, in the mother of all stoner comedies, Cheech and Chong’s Up in Smoke (1978), the duo meet when the hitchhiking Chong, disguised as a woman, gets picked up by Cheech, who only moments earlier was ogling attractive blondes out the window of his hoopty lowrider. Almost immediately, the two start smoking an enormous joint. Cheech, who remains behind the wheel, gets so high that he believes he is driving when he is actually illegally parked over a curb on the roadside. For this reason, they get arrested.

Later, C&C, who basically spend the whole movie looking to score, unwittingly drive a truck that is made of marijuana from Mexico to Los Angeles. (Smugglers have made the truck’s body out of ‘fibreweed’, which is like fibreglass only, you know, weed.) In the film’s final scene, while Cheech is driving, he drops a burning piece of hash between his legs and begins swerving around the road. Chong tries to put out the flaming ember by pouring beer into Cheech’s lap, all the while admonishing: ‘Hey, man, watch the road!’ The scene was replicated as homage in perhaps the greatest stoner movie of all, The Big Lebowski (1998).

The car is central to film’s exposition of stoner life. Driving-while-baked is shown as problematic, if hilariously so, because it is risky and sometimes scary and more likely to bring you into contact with the police than staying somewhere quiet. In other words, plenty of pop culture suggests that pot and cars are probably two things better left unmixed.

Yet, stoners themselves often argue to the contrary, that scientific evidence proves stoned driving to be safe driving. When I was in college, I heard several references to a mythological study conducted in the Netherlands – my friends would have said it was done ‘in Amsterdam’ – which showed that driving high was not only safer than driving drunk but also safer than driving straight. ‘Yeah, man,’ my trustafarian and other pothead friends would say, ‘weed makes you a little paranoid so you are more careful!’ In the flatter-than-a-pancake college town of Urbana, Illinois, the study’s findings were repeated often enough to sound like common sense.

But do such findings exist? And if so, where do they come from?

The study of alcohol and driving has a long history, as detailed in Barron Lerner’s excellent book One for the Road (2011). By the 1950s, scientists were already doing research on the psychological effects of alcohol on motor control. These studies resulted in publications that were fundamentally sound and that continue to be cited today as the predecessors of contemporary analysis. Consider the work of William Haddon, Jr, the physician who, in the late‑1950s, was the head of New York State’s driver research centre and who would go on to head the first national auto‑safety agency (now the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration). In New York, Haddon’s epidemiological research found that alcoholics who lived locally accounted for a large share of the single‑vehicle traffic accidents on the roads.

On the other hand, when it comes to marijuana and driving, the research is broad, to say the least. Most of the papers from the 1950s mention driving only in the context of court cases or juvenile delinquency. When studies of how pot influences driving began in the late-1960s, they were, as one would expect, conducted by squares; of course they found that marijuana use negatively affected driving behaviour, sometimes in the extreme.

Yet the studies had problems of two types: some were based on very limited data sets. For example, George E Woody’s ‘Visual Disturbances Experienced by Hallucinogenic Drug Abusers While Driving’ (1970) relied on ‘three case reports of young men with histories of hallucinogen use’. Woody made the drastic claim that these three men experienced hallucinations while driving but they weren’t even high: rather, they were experiencing what others might call flashbacks. He warned: ‘The author believes that use of these drugs may be introducing a new driving hazard.’

Almost all of the other studies from that time involved putting stoned people behind the wheel of driving simulators, not actual cars. Yet, simulated driving does not map perfectly onto actual driving. The divergence between simulation and reality might be especially true when high and paranoid individuals sitting in the simulator have scientists peering over their shoulders.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that researchers started conducting studies based on observations of actual driving, and that’s where the Dutch come in. Perhaps because of the Netherlands’ decriminalisation of hash and other substances, the nation’s scientists have produced many of the leading studies on stoned driving. I think it is generally fair to say that later studies have found smoking and driving to be less direly problematic than earlier studies did, though they often still assert that pot decreases driver performance along several key measures. One reason why the severity of findings might have decreased over time is that younger scholars actually used pot at some point in their lives. That is, they weren’t/aren’t older scholars worried about what the kids are up to.

But somewhere along the line, the Dutch research got twisted by the stoner community and the public at large. Proof of the mythic conclusions were said to have been published by Ramaekers et al in Human Psychopharmacology under the title ‘Marijuana, Alcohol, and Actual Driving Performance’ in October 2000. In the study, subjects either received a placebo, got stoned, got drunk, or got stoned and drunk. They then drove along a standardised test route with a licenced driving instructor who had the kinds of redundant vehicle controls often placed in driver’s-ed training cars.

The idea that pot is safer and better for you than alcohol is virtually a stoner battle cry

The cars were specially equipped with an electronic device that measured the vehicles’ distance from the left‑lane line. In this way, the core measure of the study was how marijuana, alcohol and the combination of the two influenced the car’s relationship to that lane line, a measure known as standard deviation of lateral position (SDLP). As the study explained: ‘SDLP is a measure of road‑tracking error, in practical terms, a composite index of … weaving, swerving and overcorrecting.’

Here’s what the study really found: stoned drivers perform worse than straight drivers. The worst performers of all were those individuals who got high and drunk, confirming the long-held belief that marijuana amplifies the effects of other drugs, sometimes in unpredictable ways. The study also found that driving stoned is safer than driving drunk.

This last finding is likely why potheads energetically took up news of the study. The idea that dank buds are safer and better for you than alcohol is virtually a stoner battle cry.

What appears to have happened is that the pot users I knew or people they knew got some parts of the Ramaekers study right, especially the bit about reefer versus booze. But someone in the stoner community – either willfully or through faulty memory – switched the study’s findings about straight versus stoned driving. Moreover, it’s not clear if the person who made this error was even a member of the user community in Central Illinois. It could just as easily have been a University of Illinois student’s buddy in a smoking session somewhere in the Chicago suburbs, or it could even have been something someone picked up from a cousin while on vacation in Florida or whatever. (I am setting aside the internet as a source because in 2000 many students still did not own their own computers, and went to university computer labs to do school work. At that time, I didn’t know many people who got their news from the web.)

The key point is, if the Ramaekers research was the source of this myth, someone took the study’s safety rankings of these two states of mind – straight versus stoned – and reversed them. The study was re-invented: stoned driving is better than straight driving, stoners told each other and the world, a belief that has spawned almost two generations of road trips and a galloping, cartoon fast-food sense of the American culturescape.

But things get more interesting than that. Last semester, I was discussing self-driving (autonomous) cars with students in my Computers and Society class. We were focusing on how self-driving cars will be a boon not only to those who are blind but also to serious drug addicts and alcoholics, who could, for example, go to their local watering holes, get totally loaded on gallons of Coors Light, have angry arguments settled by Wikipedia, crawl into their autonomous vehicles, and (because one model of the Google car doesn’t even have a steering wheel) press the home button. Why not?

It was in this context that students raised the classic stoned‑driving question, and I told them the story of the mythological Dutch study. The students got excited. They told me that the TV show, MythBusters, had recently reproduced just this study. What the MythBusters gang found, the students said, was that stoned drivers drove better than drunk drivers, and that experienced pot users drove much better than inexperienced ones.

This latter finding about experience is exactly what you would expect, if you have either used the drug or have read the social scientific literature on drug culture, including Howard Becker’s foundational essay ‘Becoming a Marihuana User’ (1953). Becker’s paper was based on 50 interviews with users. His central insight is that, at first, smoking pot is typically not fun. ‘Marihuana-produced sensations are not automatically or necessarily pleasurable.’

So, people have to learn how to enjoy it. Becker writes: ‘This paper seeks to describe the sequence of changes in attitude and experience which lead to the use of marihuana for pleasure.’ You aren’t going to use pot if you don’t like it. The path to these ‘changes in attitude and experience’ is through other users, who teach novices smoking technique and how to deal with the sensations of being stoned, which are ‘typically frightening’ at first. One user told Becker of novices: ‘You have to, like, reassure them, explain to them that they’re not really flipping or anything, that they’re gonna be all right. You have to just talk them out of being afraid.’

Becker paints a picture of a pothead subculture that gently soothes and instructs newbies in the ways of the world. Aficionados teach greenies how to use and enjoy weed. But these are not the only things that amateurs learn as they are inducted into the user community. For example, they are taught about music (for your rocketship). They learn rituals, like stuffing a towel under the door. They pick up rules of thumb, including the idea that it is better not to go out in public stoned until you really know what you are doing, and that making a pizza delivery order can be scary but will probably be all right in the end because others don’t know. (On the pizza delivery lesson, watch this insightful Mr Show skit, a parody of Sid and Marty Krofft’s children’s TV series, H R Pufnstuf.) Users also propagate all kinds of folklore, invented traditions and practical wisdom, including how to handle a drug deal, and who the local drug dealers are. If Becker is right, then, the last thing you would want to do is put a brand‑new user, who might be freaking out, behind the wheel of a car. Bravo! Those wily MythBusters confirmed a fundamental social-scientific picture of reality.

Given that science is one of the basic ways modern cultures build pictures of reality, it would be weird if potheads didn’t talk about ‘scientific’ things, especially ones related to their shared interests. Hey, and some stoners are scientists. Moreover, individuals are more likely to circulate ideas that support what they are already doing anyway, especially when they are feeling a touch anxious. In such an environment, it would be easy for someone to utter something false, either as an act of pure bullshitting or in a moment of misremembering, and then for that utterance to take on the status of fact.

Like the MythBusters episode. It turns out it does not exist. Or at least, I have not been able to find it after many Google searches, which I am going to assume probably means it doesn’t exist. Indeed, one of the most common things I have found through such searches is people begging MythBusters to make that very episode.

Joints aren’t the only things being passed around. So are ‘findings’

Smoke isn’t the only thing flying around the hotbox of pot culture. ‘Facts’ are flying, too. And joints aren’t the only things being passed around. So are ‘findings’.

In a recent essay entitled ‘What is Ideology?’, John Levi Martin, a professor of sociology at the University of Chicago, argues that most of our political beliefs, or ideologies, are not based on considered, rational positions, but rather arise primarily from whom we choose to associate, or affiliate, with. For example, Martin says that the traditional friction between liberals and conservatives over welfare policy comes because they ‘differ greatly… in their belief as to how worthy the recipients are,’ that is, ‘how likely the poor are to be trying to solve their own problems’. Martin goes on to say that the question over whether the poor are trying to help themselves ‘refers to a matter of external fact. We would imagine that at least one of the two positions has to be wrong.’

Martin sheds light on the subjective nature of most of our political beliefs. They come from the friends we select, the media choices we make, and the political spaces we feel comfortable inhabiting. A Tea Party enthusiast will feel comfortable at a Tea Party rally; a Hillary Clinton fan won’t. Our beliefs are largely a product of where we are in networks of others.

If my account above adds anything to Martin’s analysis of politics, it is to suggest that this picture also applies to our beliefs about science – while acknowledging, of course, that politics and science can rarely, if ever, be pried apart. After all, the subject of how weed affects driving often comes up in conversations about whether it should legalised.

We should pay more attention to how subcultures and other medium-to-small group units construct and circulate ‘facts’ that are not facts. We could examine this dynamic just as easily among progressives who hate genetically modified organisms as we could among conservatives who deny climate change. Already in the context of pot legalisation laws, we are seeing a bunch of new studies on marijuana and driving performance. And we can expect to see many more. How will groups pick up these studies? How will they be altered and reinvented?

We must be careful. We must weed through the ‘facts’ because often, in our search for truth and in our quest to live life well, smoke gets in our eyes.

Take a hit of that.