‘As long as there has been such a subject as philosophy, there have been people who hated and despised it,’ reads the opening line of Bernard Williams’s article ‘On Hating and Despising Philosophy’ (1996). Almost 30 years later, philosophy is not hated so much as it is viewed with a mixture of uncertainty and indifference. As Kieran Setiya recently put it in the London Review of Books, academic philosophy in particular is ‘in a state of some confusion’. There are many reasons for philosophy’s stagnation, though the dual influences of specialisation and commercialisation, in particular, have turned philosophy into something that scarcely resembles the discipline as it was practised by the likes of Aristotle, Spinoza or Nietzsche.

Philosophers have always been concerned with the question of how best to philosophise. In ancient Greece, philosophy was frequently conducted outdoors, in public venues such as the Lyceum, while philosophical works were often written in a dialogue format. Augustine delivered his philosophy as confessions. Niccolò Machiavelli wrote philosophical treatises in the ‘mirrors for princes’ literary genre, while his most famous work, The Prince, was written as though it were an instruction for a ruler. Thomas More maintained the dialogue format that had been popular in ancient Greece when writing his famed philosophical novel Utopia (1516). By the late 1500s, Michel de Montaigne had popularised the essay, combining anecdote with autobiography.

In the century that followed, Francis Bacon was distinctly aphoristic in his works, while Thomas Hobbes wrote Leviathan (1651) in a lecture-style format. Baruch Spinoza’s work was unusual in being modelled after Euclid’s geometry. The Enlightenment saw a divergent approach to philosophy regarding form and content. Many works maintained the narrative model that had been used by Machiavelli and More, as in Voltaire’s Candide (1759), while Jean-Jacques Rousseau re-popularised the confessional format of philosophical writing. Immanuel Kant, however, was far less accessible in his writings. His often-impenetrable style would become increasingly popular in philosophy, taken up most consequentially in the work of G W F Hegel. Despite the renowned complexity of their works, both philosophers would become enduringly influential in modern philosophy.

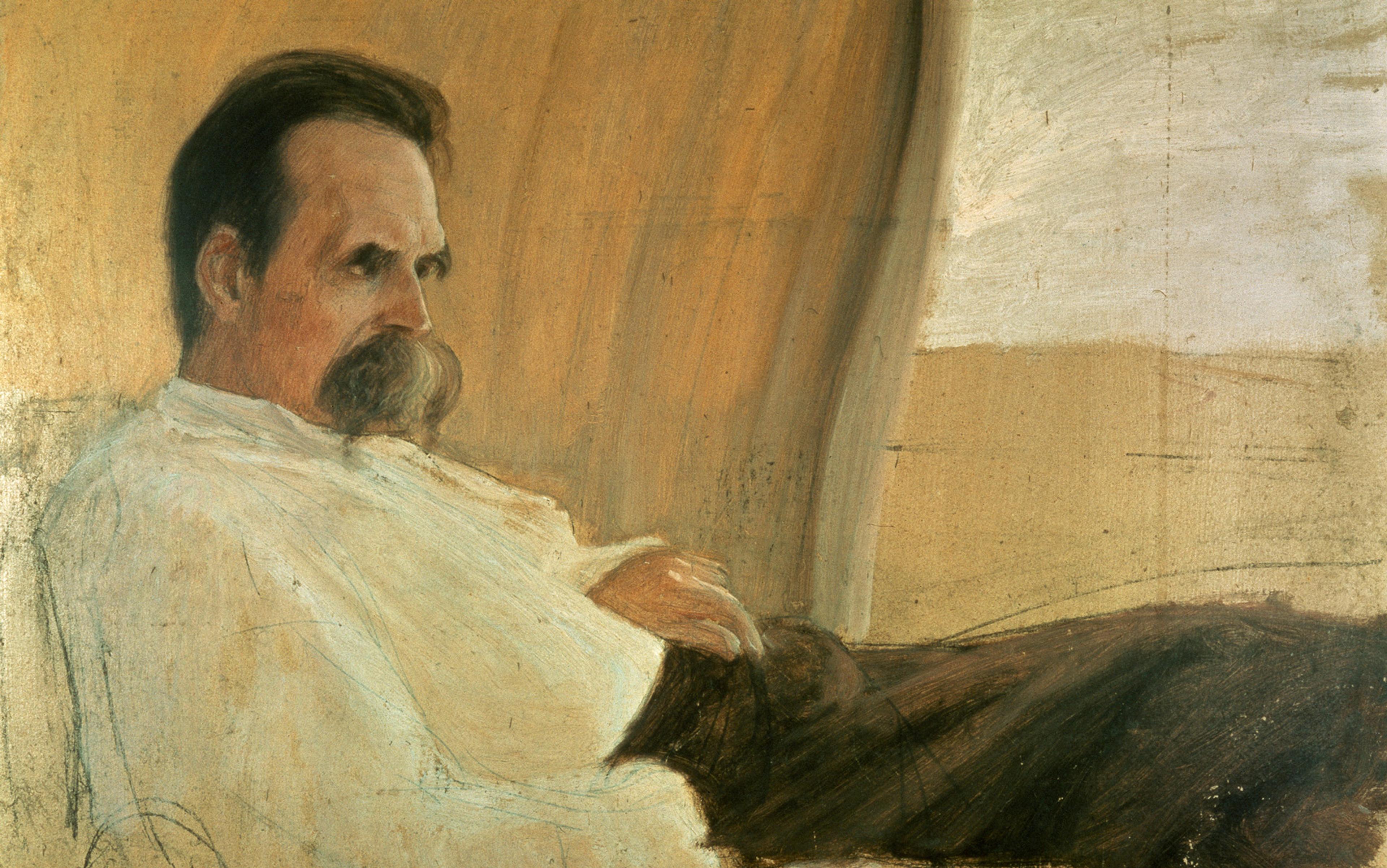

In the 19th century, Friedrich Nietzsche, greatly influenced by Arthur Schopenhauer, wrote in an aphoristic style, expressing his ideas – often as they came to him – in bursts of energetic prose. There are very few philosophers who have managed to capture the importance and intellectual rigour of philosophy while being as impassioned and poetic as Nietzsche. Perhaps this accounts for his enduring appeal among readers, though it would also account for the scepticism he often faces in more analytical traditions, where Nietzsche is not always treated as a ‘serious’ philosopher.

The 20th century proved to be a crucial turning point. While many great works were published, philosophy also became highly specialised. The rise of specialisation in academia diminished philosophy’s broader influence on artists and the general public. Philosophy became less involved with society more broadly and broke off into narrowly specialised fields, such as philosophy of mind, hermeneutics, semiotics, pragmatism and phenomenology.

There are different opinions about why specialisation took such a hold on philosophy. According to Terrance MacMullan, the rise of specialisation began in the 1960s, when universities were becoming more radicalised. During this time, academics began to dismiss non-academics as ‘dupes’. The problem grew when academics began to emulate the jargon-laden styles of philosophers like Jacques Derrida, deciding to speak mostly to each other, rather than to the general public. As MacMullan writes in ‘Jon Stewart and the New Public Intellectual’ (2007):

It’s much easier and more comfortable to speak to someone who shares your assumptions and uses your terms than someone who might challenge your assumptions in unexpected ways or ask you to explain what you mean.

Adrian Moore, on the other hand, explains that specialisation is seen as a way to distinguish oneself:

Academics in general, and philosophers in particular, need to make their mark on their profession in order to progress, and the only realistic way that they have of doing this, at least at an early stage in their careers, is by writing about very specific issues to which they can make a genuinely distinctive contribution.

Moore nevertheless laments the rise in specialisation, noting that, while specialists might be necessary in some instances, ‘there’s a danger that [philosophy] will end up not being pursued at all, in any meaningfully integrated way.’

Indeed, while specialisation might help academics to distinguish themselves in their field, their concentrated focus also means that their work is less likely to have a broader impact. In favouring specialisation, academics have not only narrowed the scope of philosophy, but have also unwittingly excluded those who may have their own contributions to make from outside the academy.

Expertise counts for much in today’s intellectual climate, and it makes sense that those educated and trained in specific fields would be given greater consideration than a dabbler. But it is those philosophers who wrote on a wide range of areas that left a profound mark on philosophy. Aristotle dedicated himself to a plethora of fields, including science, economics, political theory, art, dance, biology, zoology, botany, metaphysics, rhetoric and psychology. Today, any researcher who draws on different, ‘antagonistic’ fields would be accused of deviating from their specialisation. Consequently, monumental books that defied tradition – from Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics to Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil (1886) – are few and far between. This is not to say, however, that there are no influential philosophers. Saul Kripke and Derek Parfit, both not long deceased, are perhaps the most significant philosophers in recent years, but their influence is primarily confined to academia. Martha Nussbaum on the other hand, is one of the most important and prolific philosophers working today. Her contributions to ethics, law and emotion have been both highly regarded and far-reaching, and she is often lauded for her style and rigour, illustrating that not all philosophers are focused on narrow fields of specialisation.

But ‘the blight of specialisation’, as David Bloor calls it, remains stubbornly engrained in the practice of philosophy, and ‘represents an artificial barrier to the free traffic of ideas.’ John Potts, meanwhile, argues that an emphasis on specialisation has effectively discouraged any new icons from emerging:

A command of history, philosophy, theology, psychology, philology, literature and the Classics fostered German intellectuals of the calibre of Nietzsche and Weber, to name just two of the most influential universal scholars; such figures became much rarer in the 20th century, as academic research came to favour specialisation over generalisation.

Reading Nietzsche may at times be arduous and convoluted, but it is never dull

By demoting the significance of generalised thinking, the connective tissue that naturally exists between various disciplines is obscured. One is expected, instead, to abide by the methodologies inherent in their field. If, as Henri Bergson argued in The Creative Mind (1946), philosophy is supposed to ‘lead us to a completer perception of reality’, then this ongoing emphasis on specialisation today compromises how much we can truly know about the world in any meaningful depth, compromising the task of philosophy itself. As Milan Kundera put it in The Art of the Novel (1988):

The rise of the sciences propelled man into the tunnels of the specialised disciplines. The more he advanced in knowledge, the less clearly could he see either the world as a whole or his own self, and he plunged further into what Husserl’s pupil Heidegger called, in a beautiful and almost magical phrase, ‘the forgetting of being’.

To narrow one’s approach to knowledge to any one field, any one area of specialisation, is to reduce one’s view of the world to the regulations of competing discourses, trivialising knowledge as something reducible to a methodology. Under such conditions, knowledge is merely a vessel, a code or a tool, something to be mastered and manipulated.

By moving away from a more generalised focus, philosophy became increasingly detached from the more poetic style that nourished its spirit. James Miller, for instance, called pre-20th-century philosophy a ‘species of poetry’. Nietzsche’s own unique, poetic writing style can account for much of the renown his ideas continue to receive (and also much of the criticism levelled at him by other philosophers). Reading Nietzsche may at times be arduous and convoluted, but it is never dull. Indeed, Tamsin Shaw spoke of Nietzsche as less a philosopher and more a ‘philosopher-poet’. Jean-Paul Sartre called him ‘a poet who had the misfortune of having been taken for a philosopher’.

While many sought to separate philosophy from other creative styles and pursuits, notably poetry and literature, Mary Midgley insisted that ‘poetry exists to express [our] visions directly, in concentrated form.’ Even Martin Heidegger, whose writing was far less poetic than Nietzsche’s, called for ‘a poet in a destitute time’, and saw poets as those who reach directly into the abyss during the ‘world’s night’.

Of course, writing style alone cannot possibly account for philosophy’s floundering; Kant and Ludwig Wittgenstein proved incredibly influential despite their forbidding prose. Like Nietzsche and Heidegger, their works addressed monumental philosophical questions of being and of knowledge, altering the trajectory of philosophy itself. But as philosophy became increasingly detached from the social world upon which its interests were focused, the question about whether it had any relevance to ‘real world’ concerns, anything meaningful to say about what it meant to be human, became more frequent, and was soon the prevailing criticism whenever the topic of philosophy arose. As Bernard Williams had put it in 1996, there is the common accusation that ‘philosophy gets no answers, or no answers to any question that any grown-up person would worry about.’ Or, as David Hall argued, ‘it is the relevance of philosophy that is challenged first.’

Today, one can clearly see the effects of specialisation. Considered little more than a frivolous pastime in the 21st century, at best an elective, philosophy is seen by many to be ill suited to the vocation-oriented education system that is prioritised today. Universities provide courses that make students ‘job-ready’, while digital literacy is marketed as the benchmark of intellect and success. The infrastructure of education is almost unanimously in favour of quantified learning and STEM courses. In 2022, for instance, the Australian Research Council released its results for approved projects for 2023. Out of the 478 projects that were approved for 2023, 131 were for engineering, information and computing sciences; 117 for biological sciences and biotechnology; 98 for mathematics, physics, chemistry and Earth sciences; 93 for social, behavioural and economic sciences; and 39 for humanities and creative arts.

Stephen Hawking was one of the most vocal critics of philosophy in recent history, declaring in 2010 that ‘philosophy is dead.’ For Hawking, philosophy lacked the empirical rigour of the sciences. This wasn’t a new accusation. In Power Failure (1987), Albert Borgmann claimed that science is superior to the humanities since ‘there is always by near unanimous consent a best current theory. There never is any such thing in the humanities.’ Einstein, he wrote, ‘superseded Newton in a way in which Arthur Miller has failed to supersede Shakespeare.’ Yet what Borgmann didn’t understand is that philosophical theories are not necessarily meant to be proven or disproven, and that philosophical ideas do not simply become obsolete as new ones take shape. As Hall put it: ‘the philosopher of culture is concerned primarily not with questions of the truth or falsity of this or that interpretation, but with the articulation of those important understandings that promote cultural self-consciousness.’

Steve Jobs and Elon Musk were not the individuals he had in mind when he theorised the Übermensch

In response to the stifling impact of specialisation, certain writers and scholars have sought to rectify philosophy’s obscurity by attempting to make it more relevant to society. But in their efforts to broaden philosophy’s reach, many have simply turned philosophy into a corporate enterprise. Corporatisation – the most egregious mutation of neoliberal capitalism – has had a devastating impact on philosophy, to the extent that ideas and creativity are embraced only insofar as they are marketable and profitable.

In an age dominated by self-help, the cult of Silicon Valley and the normalisation of excessive wealth, philosophers have been demoted, replaced with ‘thought leaders’ and think tanks, influencers and entrepreneurs. Kiran Kodithala, in his article ‘Becoming the Übermensch’ (2019), even sees Nietzsche’s Übermensch as an entrepreneur, providing a particularly egregious interpretation of Nietzsche’s philosophy:

According to Nietzsche, becoming ubermensch is quite simple. His recipe is to believe in yourself and stop worrying about the world. The status quo will always resist change, the society will always call you crazy, some might even label you a narcissist, and a few might call you naive for coming up with radical ideas.

For Kodithala, Steve Jobs can be seen as one possible incarnation of Nietzsche’s elusive Übermensch, in large part due to his dogged pursuit of creativity against considerable hardships. Yet Nietzsche would have baulked at the implication, while admonishing society’s celebration of tech moguls like Jobs and Elon Musk, who have simply reinforced the status quo under the guise of entrepreneurship, rather than disrupting it. These were not the individuals that Nietzsche had in mind when he theorised the Übermensch, a concept that applied less to a specific individual than to an idea. Had Nietzsche intended for the Übermensch to apply to a specific person or persons, he would have reserved it for the greatest artists only.

For Nietzsche, art exists as the purest form of self-expression, and he held in the highest esteem figures like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Goethe and Schopenhauer who, he felt, exhibited the intrinsic spirit of self-overcoming. In the 21st century, creativity has been co-opted by industries of capital, and the very idea of ‘greatness’ has lost its meaning, increasingly applied to those who, Nietzsche would have argued, do nothing but defile culture and tarnish the very idea of creativity. Creativity is not rewarded as an end in itself, but merely as a method to accrue capital. Or, as Jenny Odell puts it in How to Do Nothing (2019), art, philosophy and poetry struggle to survive ‘in a system that only values the bottom line’; such pursuits ‘cannot be tolerated because they cannot be used or appropriated, and provide no deliverables.’

To this end, great philosophical works have been replaced by pop philosophy books that are more closely associated to the self-help industry than to philosophy itself. Alain de Botton is one of the more familiar figures whose place in contemporary philosophy attests to this shift; his School of Life organisation (comprised of a large production team) has turned philosophy into a business aimed at selling gimmicky merchandise under the guise of contemporary enlightenment. While his desire to breach the gap between philosophy and the general public is certainly commendable, his efforts are at once a help and a hindrance to the nature of philosophy itself. On the one hand, his books attempt to ‘modernise’ philosophy for a broad readership that might otherwise be unfamiliar with such concepts or philosophers, while on the other his particular brand of modernising the field threatens to reduce philosophy and philosophical concepts to a gimmick for curing self-esteem issues. Titles such as How Proust Can Change Your Life (1997) and How to Think More About Sex (2012) share nothing with the great works of philosophy, while promoting the harmful notion that, if philosophy is to have any value now and beyond, it must base its worth on its practical use-value as an antidote to society’s psychological sickness.

De Botton is not alone in this treatment of philosophy as a self-help marketing device, as an alarming number of so-called ‘philosophy’ books sold today are merely self-help books masquerading as philosophical treatises. One such book blurbs: ‘How can Kant comfort you when you get dumped via text message? How can Aristotle cure your hangover? How can Heidegger make you feel better when your dog dies?’ Certainly, none of these philosophers ever intended their work to be used in such a way.

In her scathing review of Colin McGinn’s poorly received The Meaning of Disgust (2011), Nina Strohminger called the book ‘an emblem of that most modern creation: the pop philosophy book. Actual content, thought, or insight is entirely optional. The only real requirement is that the pages stoke the reader’s ego, make him feel he is doing something highbrow for once.’

There is a feeling among younger readers that philosophy is in want of a clearer identity or direction

These books may, of course, prove useful to many people, but they also risk trivialising our expectations regarding what philosophical and critical thinking is supposed to feel like. As Christian Lorentzen put it in the London Review of Books in 2020: ‘Many people buy books that supply the illusion of thinking …’ These books can help introduce readers unfamiliar with philosophy to the thoughts and ideas of some of the great philosophers, but they stop short of demanding more critical engagement from readers. At most, they can make readers feel a bit better, not an unworthy goal, but not at all one with which philosophy itself is concerned. As the philosophical biographer Ray Monk has argued, these books ‘might have a purpose.’ ‘But,’ he adds: ‘that’s not philosophy.’

In his book The Nature and Future of Philosophy (2010), Michael Dummett asks: ‘Where, then, is philosophy likely to go in the near future?’ It is a question that many people, both philosophers and non-philosophers, often ask. In fact, as Kieran Setiya recently pointed out, it isn’t uncommon for people to lament the state of philosophy. He specifies that philosophers of a certain age tend to deplore the discipline’s lack of direction, or the lack of great, influential figures. But there is an overwhelming feeling among younger readers and practitioners that philosophy is in a particular stage of uncertainty or stasis, and that it is in want of a clearer identity or direction.

Dummett recognised that specialisation and the various opposing traditions that emanated from this has had no small impact on philosophy’s future: ‘[T]he gravest obstacle to communal progress in philosophy has been the gulf that has opened between different traditions.’ Dummett puts forth the argument that the most fruitful path taken in philosophy has been the analytic tradition, whose chief interest has been language. Though he believes the analytic tradition has certain strengths over the continental focus on phenomenology, he also sees potential in a ‘reconciliation’ between these traditions, believing such a union could be best met through a mutual focus on the philosophy of mind. Both scientists and philosophers, he contends, have become obsessed with the idea of consciousness, an area that may, he reasons, see these divergent traditions meet each other halfway.

Yet there is still the larger problem of the lack of understanding regarding philosophy’s identity. Pop philosophy has flooded the market, adding to the confusion about what philosophy actually is and what it does. On Penguin Australia’s ‘pop philosophy’ site, the publisher promotes a list of books – by writers such as de Botton, A C Grayling and Marie Robert – that offer ‘some pearls of wisdom to help steer you through your day’. Promoting pop philosophy is one thing; one might expect that a separate search for ‘philosophy’ on Penguin’s website would at least yield more substantial results. Instead, one is met with an incongruous mix of works by Jordan Peterson, Marcus Aurelius, Stephen Fry, and Seneca. It is perhaps no surprise that philosophy is in such a state of confusion, when classic philosophical works appear alongside lightweight self-help books, as if they are interchangeable. And while academic books might prove more substantial in their offerings, they are notoriously and often prohibitively expensive, meaning they are largely ignored, or read almost exclusively by other academics.

There is a disconnect between philosophy as it was practised by the likes of Nietzsche, Heidegger and Kant, and what readers are being offered today. Corporatisation and commercialisation have not only dulled people’s tolerance for critical thinking but have warped their expectations about what it means to read philosophy, seeing it only as something that can make them happier. But as Monk reminds us: ‘Philosophy doesn’t make you happy and it shouldn’t. Why should philosophy be consoling?’

Nietzsche himself recognised that philosophy can be an unsettling endeavour. In his final book, Ecce Homo, he claimed that philosophy is ‘a voluntary retirement into regions of ice and mountain-peaks – the seeking-out of everything strange and questionable in existence.’ He wrote: ‘One must be built for it, otherwise the chances are that it will chill him.’

Nietzsche did not see himself as a philosopher in the traditional sense

In 2005, two years before his death, Richard Rorty similarly noted that ‘philosophy is not something that human beings embark on out of an inborn sense of wonder …’ Instead, Rorty believed that philosophy is ‘something [people] are forced into when they have trouble reconciling the old and the new, the imagination of their ancestors with that of their more enterprising contemporaries.’ David Hall once argued that:

[I]t is the primary function of the practising philosopher to articulate cultural self-understanding. And if the philosopher fails to provide such an understanding, he fails in the task that is his very raison d’être.

Philosophy, of course, is not meant to be for everyone, and Nietzsche knew this. It is easy to see why Bertrand Russell felt that Nietzsche was elitist, when Nietzsche claimed: ‘These alone are my readers, my rightful readers, my predestined readers: what do the rest matter? – The rest are merely mankind.’ Yet, in many ways, Nietzsche’s works exemplify philosophy at its best. They were not academic in nature, but nor were they overtly commercial. They were impassioned works of tremendous literary force. Nietzsche did not see himself as a philosopher in the traditional sense, which helps to explain his unconventional place in philosophical history. But Nietzsche nevertheless saw himself as part of a collective. While Borgmann seemed to pit scientists against each other in an ongoing battle of one-upmanship, Nietzsche recognised that he was drawing on those who came before, and that his own readers would likewise draw on him. In Daybreak (1881), one of his earliest and most underrated works, he writes:

All our great mentors and precursors have finally come to a stop, and it is hardly the noblest and most graceful of gestures with which fatigue comes to a stop: it will also happen to you and me! Of what concern, however, is that to you and me! Other birds will fly farther!

Nietzsche has indeed influenced a slew of successive thinkers, though no other philosopher since has had such an enduring impact. Clearly, our century’s emphasis on quantified knowledge, specialisation and marketability has created an intellectual climate that not only devalues philosophical thought, but has turned philosophy itself into something it was never supposed to be.