Sometimes you need to look at things from outside to see them more clearly. That’s the rationale presumably for psychotherapy, marriage guidance counselling and management consultancy. But the best example on a global scale was the spectacular ‘Earthrise’ photograph from the Apollo 8 mission of 1968, which for the first time showed us our Earth from a distance. We could now see for ourselves just how wonderful and vulnerable this small planet looked from outside. That one image did more for the environmental movement than a thousand scientific pronouncements could.

History can give us the same sense of distance, and the ancient world offers a revealing perspective of time as well as place. The Mediterranean world of 2,500 years ago would have looked and sounded very different. Nightingales sang in the suburbs of Athens and Rome; wrynecks, hoopoes, cuckoos and orioles lived within city limits, along with a teeming host of warblers, buntings and finches; kites and ravens scavenged the city streets; owls, swifts and swallows nested on public buildings. In the countryside beyond, eagles and vultures soared overhead, while people could observe the migrations of cranes, storks and wildfowl. The cities themselves were in any case tiny by modern standards – ancient Athens, for example, had a population of about 120,000 at the height of its power in the 5th century BC, compared with its modern metropolitan equivalent of some 3.7 million. And most townspeople were intimately involved in the life and produce of the countryside around them, anyway. Rus in urbe was a reality, not an illusion of municipal planning.

Detail from a fresco with birds in a garden from the House of the Golden Bracelet in Pompeii, 30-50 CE. Photo By DEA/L Pedicini/De Agostini via Getty

Small wonder, then, that birds impressed their physical presence on people’s daily lives, to a degree now hard to imagine. There they were – visible and audible at most times of day; occupying all the domains of land, sea and air; and in an abundance and diversity we can only dream of today. Not surprising either, therefore, that they also populated people’s minds and imaginations and re-emerged in their culture, language, myths and patterns of thought in some symbolic form. This progression from daily familiarity to symbolic representation must be what Claude Lévi-Strauss had in mind in the much-quoted dictum, taken from his book Totemism (1962): ‘Les espèces sont choisies non comme bonnes à manger, mais comme bonnes à penser.’ The last phrase is usually rendered in English by the epigrammatic: ‘Animals are good to think with.’ Not an exact translation but a suggestive manifesto.

Birds were certainly ‘good to think with’ in the ancient world. They crop up in all manner of figures of speech, proverbs, myths, fables, and in ritual and magical practices, some of which now seem very strange. But let’s start first with some more familiar instances.

Birds have always been important ‘markers’, associated with particular seasons, times and places. In the ancient world, weather and seasonal changes were matters of vital consequence for agriculture, travel, trade and the rounds of domestic life, and birds served as a standard point of reference in calibrating and interpreting the cycles of the year. In Works and Days (c700 BCE), one of the earliest works in European literature, Hesiod refers to the migrations of the crane, cuckoo and swallow as timely reminders to farmers for different seasonal tasks on the land. For example, on the departing cranes in autumn:

Take note when you hear the clarion calls of the crane,

Who yearly cries out from the clouds above.

He gives the signal for ploughing

And marks the season of rainy winter.

Similarly, the cuckoo is the wakeup call for farmers to look lively in the spring:

When the cuckoo is first heard from the spreading oak-leaves

And gladdens men’s hearts across the wide world …

then the late ploughman can catch up the early one.

Keep all this in mind and don’t fail to observe

The greening of grey spring and the season of rain.

Now as then, Hesiod notes, the swallow was the most common seasonal marker:

Next comes the swallow …

Returning to humankind in the light of spring.

And it’s best to prune your vines before she comes.

The comic playwright Aristophanes has more homely advice in his fantasy play, The Birds:

Here comes the swallow – time to sell those winter woollens

And buy yourself something more summery.

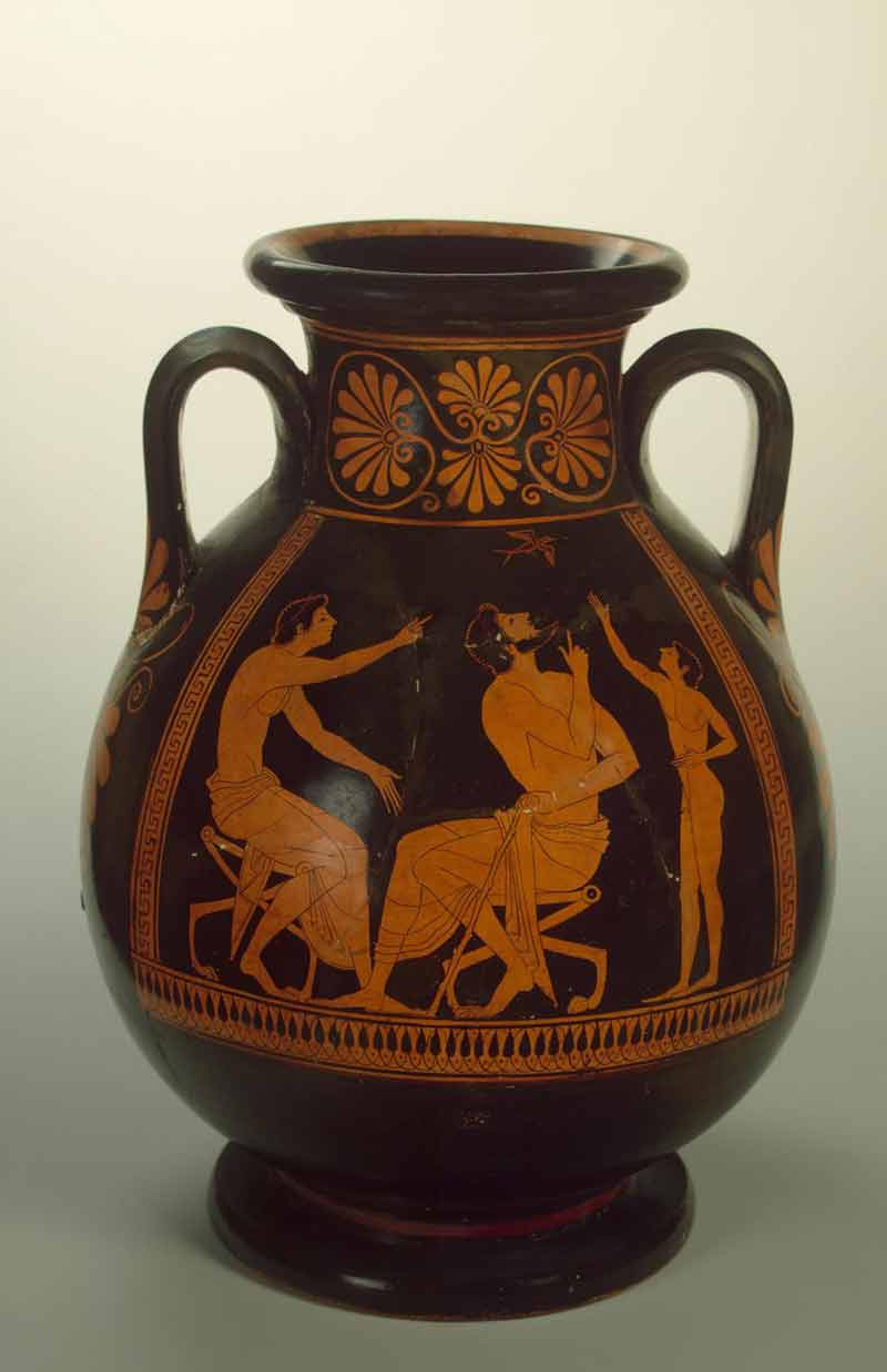

And this charming cartoon on a 6th-century Greek vase illustrates the role of the swallow as a sign of spring:

Attic red-figure vase, 515-505 BCE. The speech of the figures (not visible here) say: ‘Look, a swallow.’ ‘Good Lord, so it is.’ ‘There it goes.’ ‘It’s spring already!’ Courtesy the State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

In On Animals, the encyclopaedist Aelian (c165-235 CE) expands on the idea of a sign that is also a symbol:

The swallow is the sign that the best season of the year is coming to stay. It is a friend to humankind and is glad to share a roof with its fellow beings. It arrives uninvited and departs in its own good time when it chooses. And people welcome it according to Homer’s laws of hospitality, which bid us cherish a visitor while he is with us and speed him on his way when he departs.

Here we see a simple progression from a descriptive fact about a bird (swallows migrate here the same time every spring), to a human comparison (that’s when we change what we wear, too) and then, in a natural and almost imperceptible segue, to making the bird represent something other than itself (a sign of spring, a reminder to start gardening, a valued guest). That is, a metaphor, something that ‘carries us across’ from one dimension of meaning to another. It seems to be a distinctive human capacity to be able to make such conceptual and linguistic moves, and it was a key factor in our cognitive evolution.

The heightened languages of literature and art depend on creative, metaphorical moves of this kind. Birds enter popular culture from the earliest times, and they continue to pervade literature and art throughout the classical period. They are mentioned in the very first sentence of European literature – as scavengers, at the start of Homer’s Iliad. They feature repeatedly in subsequent epic, lyric, didactic, pastoral and personal poetry, in tragedy and comedy, in epigrams and invective, and in prose writings on geography, history, travel, medicine and early science. And not just birds as a generic phenomenon: Aesop features nearly 30 different species of birds as the principal characters in his moralising Fables, and the playwright Aristophanes mentions a remarkable 75 species in his political and social satires. How many species, by contrast, would you find in the works of our contemporary, Tom Stoppard?

Just as birds inaugurate European literature, so one of the first images in European art features swallows, again in an unmistakeable celebration of spring.

Detail of swallows and lilies from the ‘Spring Fresco’ in the Minoan palace at Akrotiri in Thera (Santorini), c1650 BCE. Courtesy Wikipedia

In the wonderful wall paintings that have survived the Pompeii holocaust of 79 CE, we can identify nearly 80 different species of birds. Birds also appear in many other media and as design motifs – on domestic pottery, coins, seals, mosaics, personal ornaments and in sculpture.

This wealth of references in popular culture mirrors the abundance and ubiquity of birds in the classical world. These references would not have made any sense to their audiences and viewers unless there was a general familiarity with the birds in question – to a degree almost unimaginable today. To the consternation of naturalists, Oxford University Press in 2012 dropped from its Junior Dictionary the names of once-familiar birds such as heron, kingfisher and magpie. The reason? Young people in their target age-group no longer use these words or recognise the species in question. The modern ABC is not acorn, bluebell and conker (all dropped from the dictionary as well), but attachment, blog and chatroom.

Proverbs encapsulate this kind of folk knowledge. Various ancient proverbs involving birds had their counterparts in English, though, like the birds themselves, our use of them is now fading and disappearing. The following proverbs are almost identical in Ancient Greek or Latin and in English:

One swallow doesn’t make a summer

Birds of a feather flock together

A bird in the hand

A cuckoo in the nest

But when did you last hear a cuckoo? Will that proverb continue to have a meaning for future generations, if the bird itself is not part of their experience? And how about Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s ‘the moan of doves in immemorial elms’? The elms have gone from England, and the turtle doves have almost gone too.

By contrast, ancient proverbs still had a freshness and vitality. Others include:

Go to the crows (rot in hell)

To throw a vulture (an unlucky cast of dice)

Further than a kite roams (a huge distance)

Birds love figs but won’t plant them (no pain, no gain)

Eagles don’t catch flies (don’t bother with trifles)

Owls to Athens (coals to Newcastle)

This last one makes the point. From the 1500s, Newcastle-upon-Tyne was a principal centre for coal exports in Britain. The coal industry is now extinct there, however. The proverb survives but already sounds quaint. The Athenian owls, by contrast, were both the literal little owls common around the Acropolis and also metaphorical ‘owls’, the colloquial name for the four-drachma Athenian coins that had Athene’s portrait on one side (as the patron of the city) and, on the other, a little owl (the bird sacred to her). The coins are still known as ‘owls’ in the numismatics trade, and the link with the goddess is memorialised in the little owl’s scientific name Athene noctua (‘Athene by night’).

Silver Athenian tetradrachm, 5th century BCE. Courtesy Wikipedia

Metaphors, whether visual or verbal, work by having one thing standing symbolically for another. Homer’s Iliad and the Odyssey are both full of figures of speech taken from the natural world and in particular from birds. Homer describes the mustering of the Greek armies on the plain as being ‘like the clamouring flocks of cranes and wildfowl on migration’; the disloyal maidservants are strung up by Telemachus ‘like thrushes caught in a snare’; Odysseus’ bow-string ‘sings to his touch like a swallow’; and Penelope nightly mourns her absent husband ‘like a wailing nightingale’; while Homeric heroes bear down on their opponents in battle ‘like marauding eagles’.

Aristophanes takes the bird-as-metaphor to comic extremes. In The Birds, there is an outbreak of ornithomania (bird madness) in Athens, and everyone wants to take on bird names, sing bird songs, buy wings and join the birds in their kingdom in the sky (which was called Cloud Cuckoo Land – that’s where that phrase comes from):

That’s the news from Earth, and I can tell you this:

there’ll soon be thousands of them heading this way,

all wanting wings and the full kit for living like birds.

So, you’d better lay in supplies for a wave of immigrants.

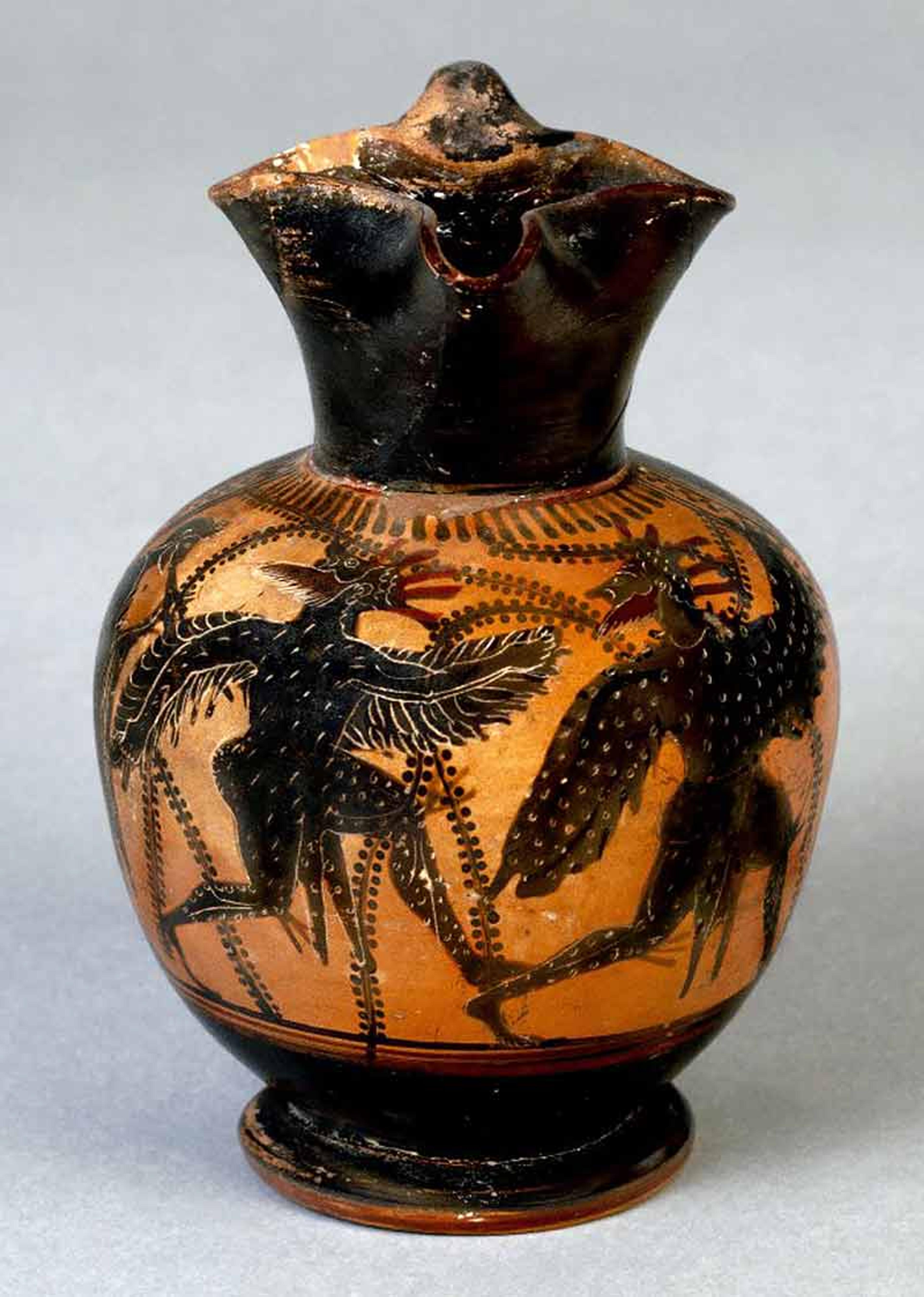

Two men in full-body bird costumes, including feathered wings and coxcombs, followed by a piper, on an Attic black-figure wine jug, 500-490 BCE. Courtesy the Trustees of the British Museum

Myths and fables are metaphors writ large. In Ovid’s enchanting stories in his Metamorphoses, birds far outnumber mammals – about 50 against two, at a rough count – and differ also in that the bird stories are always aetiological. That is, they are ‘just so’ stories explaining how the species acquired their distinctive features (and often their names). Picus had been changed by Circe into a woodpecker, and vents his anger by violently drilling into trees; Perdix was thrown from a high tower, and now clings close to the ground as a partridge; and Ovid gives us similar myths about Cygnus the swan, Tereus the hoopoe, Philomela the nightingale, and so on.

It’s an easy step to go from these fantasies to the world of dreams. Writing in 1899, Sigmund Freud was in no doubt about their importance to understanding our inner imaginings and aspirations: ‘The interpretation of dreams is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind.’

Freud regarded this as one of his most important discoveries, but he was gracious enough to acknowledge an ancient predecessor, Artemidorus of Daldis, who produced a massive work of dream interpretations in the 2nd century CE. But while Freud was concerned to analyse dreams as a means of understanding the past history and present pathology of his patients, Artemidorus saw them as portents of future events. Artemidorus’ case studies include many references to birds as symptomatic indicators. If you dream of cormorants, for example, that portends a dangerous sea-voyage (but not a fatal one, since cormorants ‘can submerse without drowning in the sea’). Similar diagnoses involve hawks and kites (robbers and bandits); starlings (disorderly crowds); a fall of quail (an insurgence of immigrants); vultures (imminent death); swallows (reminders to do your DIY on the home); storks (auspicious for child-bearing and marriage – still a modern fancy); and, of course, flying itself (freedom). What is interesting here is not the predictive value of these interpretations (almost zero), but the species selected, the knowledge about them that is assumed, and the recognition that such symbols can have a powerful effect on human thoughts and behaviour.

Artemidorus’ dream interpretations were a special and later case of a much longer tradition of seeing birds as ‘signs’. The gods chose birds as the principal agents through which to reveal their will to humans. In one passage from Aristophanes, they describe themselves as gods’ messengers and privileged intermediaries who should be consulted about all future plans and important decisions. The chorus of birds here explains to their human visitors the benefits they bestow on humankind:

You don’t start on anything without first consulting the birds,

whether it’s about business affairs, making a living, or getting married.

Every prophecy that involves a decision you classify as a bird.

To you, a significant remark is a bird, you call a sneeze a bird,

a chance meeting is a bird, a sound, a servant, or a donkey – all birds.

So clearly, we are your gods of prophecy.

That makes little sense as a translation, until you realise that the Greek word for a bird, ornis, was also their word for an omen. The passage is an extended play on words in which the significance of birds as omens is encoded in the language itself. All the things referred to as ‘birds’ turn out to involve common superstitions that need an appropriate reaction. Saying, for example, that a sneeze was ‘a bird’ is a bit like our saying ‘bless you’ to ward off evil.

The turkey, Franklin wrote, is ‘a much more respectable bird, and withal a true and original native of America’

Since birds were in this sense ‘signs’ that helped to explain the workings of the world and the will of the gods, people needed specialists to help interpret bird behaviour. Early practitioners of this skill were variously known as oionoskopoi (bird-watchers), oionistai (bird interpreters) or oionopoloi (bird experts), and they appear regularly in classical literature from Homer onwards to advise on matters of state and military strategy. In the Iliad, for example, you have on the Greek side Calchas, ‘by far the best expert on birds, who knew things present, future and past’, while on the other side was Helenus ‘by far the best bird man in Troy’. The Roman word for this profession was an augur or auspex, from which we get the word ‘auspicious’ (from the Latin ‘watching birds’) and, as you might expect from the Romans, they put the whole thing on a more organised basis. Generals in the field, however, often disputed the auguries when they didn’t suit their plans and, as Cicero remarked, there was scope here ‘for a little error, a little superstition and a great deal of fraud’.

Big birds of prey, in particular eagles, were the most significant omens. Their evident power and aggression made them obvious military symbols, and their appearances signified good or bad luck for any proposed attack, depending on how their behaviour was interpreted. The Romans adopted the eagle as the regimental standard of their legions, the aquila, a symbol for which the legionaries were expected to fight and, if necessary, die. Indeed, many of the world’s armies have since marched under the same emblem and for the same reasons. This illustrates, too, how just one perceived characteristic of such ‘natural symbols’ gets selected for emphasis. The architects of the American Revolution chose the eagle as the official symbol to express and validate their national ambitions, and it is portrayed widely on American coins, banknotes, stamps and flags. But in the lively debate among the founders in making this decision, Benjamin Franklin at one point advocated for the turkey on the grounds that it was a native American bird and, unlike the bald eagle, not a predator. The turkey, Franklin wrote to his daughter, is ‘a much more respectable bird, and withal a true and original native of America’.

Eagle motifs in national emblems. Courtesy Wikipedia

Our ordinary language is still full of examples of birds used as analogies and metaphors. We talk of craning our necks, larking about and swanning around. We make verbs of rook, quail, crow, grouse and snipe. We identify our politicians as hawks or doves. And we criticise people as a dodo, albatross, vulture, magpie, gannet or a bit cuckoo, without pausing to think about the origins or accuracy of these expressions, which have taken on a life of their own. We then project these conceptions back on to the world in the form of symbols – on national flags, stamps and coins, on church lecterns, on street and pub names, on sports teams and their logos, and on all manner of branded designs.

Why then should it be birds – of all life forms – that seem such good vehicles for representing human relationships with the natural world? Their sheer ubiquity and physical presence must be one major factor. Mammals, by contrast, are less conspicuous, more often shy or nocturnal, and always earth-bound. Fish are limited to just one domain and neither they nor insects prompt the same kind of human response.

In size and scale, birds are like miniature human models – bipeds with round heads and forward-facing eyes, which is presumably why owls and penguins are among the most easily anthropomorphised of all birds and dominate the soft-toy departments. Birds behave like us, too. We can observe them walking, socialising, singing, fighting, courting, homemaking, feeding and parenting. We can relate to their purposes and activities. Above all, birds enjoy the gift of flight – a deep and ancient human aspiration, signifying liberation, as expressed in the myth of Daedalus and Icarus and in many longing cries in Greek tragedy:

O for the wings of a swift dove,

to be borne upwards on eddies of air

and gaze down from the clouds on the fray

– from Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus, lines 1079-81

Then as now, this is surely why birds feature so strongly as metaphorical messengers. They are ideally, and uniquely, constructed – both physically and symbolically – to be the links between humankind and other worlds. ‘Winged words’, in Homer’s expression, bearing signs and meanings.