At around three o’clock, on a warm and beautiful summer day, the headwaiter approached Hans Kohn’s table. It was 1914, and Kohn was tucked away with a friend in the cool and quiet Café Radetzky in the Malá Strana area of Prague, preparing for his upcoming bar examination. Sunday strollers crowded the city’s streets and parks while people chatted over beer and coffee in the open air. All presumably an unwelcome distraction for the two young law students.

The waiter’s hand trembled as he handed them a special edition of a local newspaper. It announced that Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, had been assassinated in Sarajevo. The mood in the country would quickly move from bewilderment to belligerence, driving Austria-Hungary into a disastrous world war. Four years later, the country was gone from the map of Europe.

On that warm June day in 1914, few anticipated a war that would reshape the political map of Europe. When Kohn was mobilised into military service, he had expected to be home by Christmas. Instead, he ended up among the unlucky hundreds of thousands captured by Russian troops and cursed to spend the war deep in the Russian imperial interior.

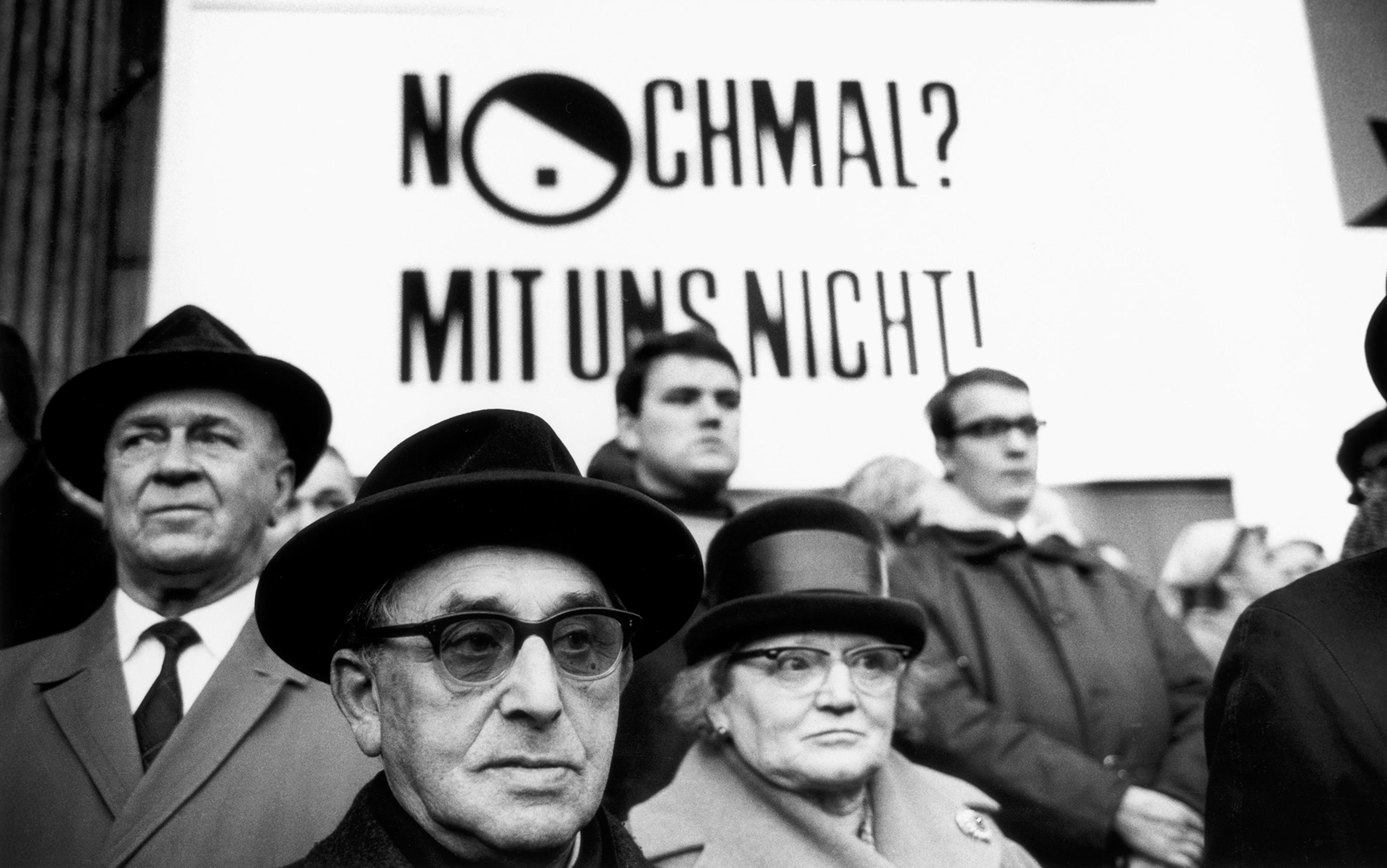

Hans Kohn in the uniform of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1914. Courtesy the Leo Baeck Institute New York

By 1920, when Kohn had made it back to Europe, Prague was the capital of Czechoslovakia, one of several new nation-states that had sprouted up during his absence, based on the principle of national self-determination. These new nation-states replaced the vast multinational – or anational – empires that had previously blanketed central and eastern Europe: the others being the German, Russian, and Ottoman Empires.

Conflicts between various nationalist movements had plagued Habsburg-ruled Austria-Hungary in the decades before its collapse. Once the war was obviously lost, the path was open for them to take over from the delegitimised and eventually deposed Habsburg dynasty. An even more radical nationalism would flourish in the successor states of the various empires. Germany under the Nazi regime – the largest of all – elevated racialist nationalism into the organising principle of its eastward conquests, finding no shortage of local collaborators keen to settle scores with their supposed national enemies.

Countless millions would perish in the orgy of violence unleashed by their messianic nationalist dreams, including the majority of Prague’s Jewish community to which Kohn had once belonged. In the wake of the Second World War, 12 million Germans were sent westwards out of fear or retribution. All the Allied powers agreed that the surest guarantee of future stability for central and eastern European nation-states was to have as few ethnic minorities as possible. Kohn’s youth in fin de siècle Austria-Hungary had been spent in one of the most ethnically diverse countries in Europe. By the mid-20th century, its former territories hosted some of its most homogeneous.

For Kohn, the real culprit for the downfall of his multinational homeland was not the war itself, but the force of nationalism that in its waning years exerted such a powerful sway over its people. He was hardly alone in this assessment. For at least three-quarters of a century, central and eastern Europe has served as the prime example of the pitfalls of nationalism. In particular, of the kind of ethnic nationalism that, we are often told, is characteristic of this non-Western world.

It was this particularly central and eastern European ethnic nationalism, this perspective goes, that was responsible for the collapse of the diverse and cosmopolitan Habsburg Monarchy. For the failure of the new democracies that took over from empires in 1918 – Germany, Austria, Poland, Czechoslovakia and others. And for the rise of authoritarian and fascist regimes in their place, the largest of which would go on to perpetrate the most horrific genocide in human history in the Holocaust.

According to this orthodox view, the essentially ethnic nature of central and eastern European nationalism contrasts starkly with that of the Western democracies of France, the United Kingdom and the United States. They are characterised as thoroughly civic nations, based not on supposedly primordial tribal identity, but on common citizenship and a democratic understanding of politics. In all three, the US, UK and France, their civic nationalism is a centuries-old tradition, dating back to their foundation as modern nations.

Kohn was the first historian to systematically seek out the roots of this divergence between the nature of nationhood in the Western democracies, and the central and eastern European countries in his weighty book The Idea of Nationalism (1944). Kohn’s book grew into a foundational work of ‘nationalism studies’ in the Anglophone world and has influenced generations of scholars and readers alike. He did not just see Western and non-Western nationalisms as different, but came to believe they were, in effect, totally different phenomena.

The assimilation of minorities into the dominant ethnicity in Western nation-states was celebrated as progress

Kohn argued that Western nationalisms were ‘based upon liberal middle-class concepts … pointing to a consummation in a democratic world society’, while central and eastern European nationalisms derived from ‘irrational and pre-enlightened concepts … tending towards exclusiveness’. The enlightened Western ones, he claimed, developed in France, the UK and the US, the primordial superstitious ones in Germany, before spreading across the rest of central and eastern Europe and, eventually, the world. The backwardness of all non-Western countries apparently made it all but predetermined that the latter would win out over the former.

While the distinction between these two kinds of nationhood was known to 19th-century thinkers, the notion that ethnic and civic aspects of nationhood were necessarily in conflict, or that one or the other was purely characteristic of a certain part of Europe, was not. Western ‘civic’ nation-states have always been built on the dominance of certain ethnic groups with their own language, traditions and myths of origin and distinctiveness. Indeed, the assimilation of minorities into the dominant ethnicity in Western nation-states was celebrated as progress.

Central and eastern European nationalists did not ‘reject’ the civic values of their Western counterparts but tried to follow them closely. They acknowledged civic rights for all that lived in a given nation-state but sought – like their Western counterparts – to eventually see all ethnic, linguistic or religious minorities assimilated into the general civic nation that was ultimately shaped by the dominant ‘state-forming’ ethnic group.

They were in awe of the assimilatory power of the English language and its culture in Britain or North America, and of the French equivalents ultimately defined in and around Paris. That German or Hungarian nationalists wanted to see Slavs or Jews shed their culture and become true Germans and Hungarians did not reflect some ‘irrational and pre-enlightened’ exclusivism. It simply reflected the reality of the Western nation-state.

Nevertheless, in nationalism studies, this geographic distinction between Western civic and non-Western (or ‘Eastern’) ethnic nationalism remains one of the most deeply engrained orthodoxies. The problem is it simply isn’t true. To understand how this misleading but influential view took shape, it is necessary to understand how the descent into ethnic extremism in early 20th-century central Europe shaped the enduring works of early theorists of nationalism. Many of whom – like Kohn himself – were ultimately shaped by its consequences, their work marked by a deep desire to discover where the histories of their homelands had ‘gone wrong’.

Kohn was born in 1891 in Austria-Hungary, perhaps the most bewildering state in modern European history. In fact, it wasn’t one state at all, but two. The half colloquially referred to as Austria consisted of three kingdoms, six duchies, two archduchies, a grand duchy, two margraviates, two princely counties and a free city, all with their own unique histories, identities, flags, forms of patriotism, celebrations of belonging and more. The other, Hungarian half itself had a kingdom within a kingdom in Croatia-Slavonia.

Profile portrait of Hans Kohn. Courtesy the Leo Baeck Institute, New York

What united all these political entities was the emperor-king Franz Joseph, who sat atop the Habsburg dynasty that had ruled most of these polities for centuries. With two brief interruptions, the Hapsburg family, from the 15th century to 1866, had acted as hereditary heads of the entirety of today’s Germany, first as Holy Roman Emperors and then as ‘heads of the presiding power’ of the German Confederation, itself consisting of 39 different German states.

This bewildering political tapestry did not make for simple nation-building on the Western model. France and Britain were centralised, but central Europe was decentralised. The former had dominant national languages, but the latter was extremely multilingual. The former had strong centres of political authority, the latter diffuse and overlapping ones. Kohn’s hometown of Prague was the historical capital of the Kingdom of Bohemia sandwiched between the Austrian duchies to the south and the rest of Germany to the north. It was a prime example of the kind of national complexities arising from this complicated Habsburg inheritance.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Bohemian natives nurtured wildly different visions of their homeland’s place in a possible national state. Most German-speaking Bohemians envisioned it as a part of Germany or a German-dominated Austrian state. Nationally conscious Bohemian Slavs variously imagined it as part of a wider Slavic-Austrian state, a more narrowly ‘Czechoslovak’ one, a purely Czech one, or even a bilingual Czech-German nation-state.

Only after 1871 did the idea that civic borders should conform to ‘objective’ national ones based on ethnic criteria come to prominence

The problem faced by all nationalisms emerging out of central Europe before 1918 was that no ethnic nation was congruent with the state. Insofar as German or Czech-speaking nationalists in Bohemia, for example, saw their nation as the one truly representative of the kingdom, they would have to assimilate their rivals against their will. Or, as Kohn maintained, ‘redraw the political boundaries in conformity with ethnographic demands’, supposedly one of the tenets of ‘non-Western’ nationalisms.

Somewhat bizarrely considering nationalism captivated Europe only in the 19th century, Kohn concluded The Idea of Nationalism with the 18th, content that he had discovered the roots of the two nationalisms by then. Yet the historical record contains very few demands from 18th- or even 19th-century eastern and central Europeans for the redrawing of borders. The first example of ‘objective’ ethnographic measures being used as the basis for border changes in Europe was in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, and there its goal is only the exchange of a few villages on the initiative of an entrepreneurial statistician.

Only in the decades after 1871 did this idea that civic borders should conform to ‘objective’ national ones based on ethnic criteria come to prominence. Importantly, it arose with the maturity of nationalist movements, not at their birth. For most of the 19th century, we find political or civic nations in central Europe seeking to assert their rights to manage their own affairs while opening up the boundaries of the nation to people of wildly diverse religious or linguistic backgrounds. In return, however, they asked for assimilation, that outsiders identify with the political community of the state and its leading ethnic group. Sometimes – as in Bohemia – competing claims arose about the question of which ethnic group had the right to be identified with the political nation.

Scholars usually date the emergence of modern nationalism to the 18th century. But it’s also true that the word ‘nation’ has been used in Europe for centuries. What changed is the modern claim that nations consist of the ‘masses’ and the modern nationalist assertion of the rights of those masses to statehood. That’s what we call ‘nationalism’.

But for a long time before modern nationalism, the word ‘nation’ frequently referred to political nations in premodern Europe. That is, the nation as a corporate group consisting of those whose rights and privileges marked them out as a distinct group in and above society. Whose privileges made them the group that ruled society, complete with their own language, customs, traditions and identity. This is why one of the great innovations of the French Revolution was the extension of nationhood through political emancipation to the broad masses of French society.

Kohn saw the romantic veneration of the common folk as the root of reactionary non-Western nationalism

The nobilities of the Habsburg-ruled kingdoms – of diverse ethnic and linguistic origins – had strong and well-developed conceptions of belonging to a common nation. So strong, in fact, that they resisted incorporation into the kind of centralised absolutist states characteristic of 18th-century Europe. The Habsburg Monarchy was nearly torn apart by the pressures of such policies pursued by Joseph II, who rescinded most of them on his deathbed in 1790.

In the kingdoms of Bohemia, Hungary and Croatia, nationalism was pioneered in the 19th century by patriotic nobles keen to assert their ‘state right’. That is, their political sovereignty as a corporate nation with the right to manage their own affairs. They were aided by small groups of middle-class publicists and scholars who, under the strong influence of German romanticism, sought to reform and cultivate vernacular languages native to the kingdoms, build narratives of historical continuity for the nations, and educate the broader masses in order to make them productive members of the nation at large. Kohn saw exactly this romantic veneration of the common folk as the root of reactionary non-Western nationalism.

He even claimed in The Idea of Nationalism that, after 1806, local central European elites proclaimed ‘the uniqueness of the folk … as an aggressive factor in the struggle against Western society and civilisation.’ An exaggeration of the role played by some nationalist publicists during the Napoleonic Wars, whose vitriolic anti-French views were more important to Wilhelmine or First World War-era German nationalists than 19th-century ones.

German liberal nationalists of the first half of the 19th century contrasted their envisioned nation-state not with Western society and civilisation, but with the reactionary princely confederation in which they lived. When national revolts broke out in Greece or Poland, German nationalists cheered their fellow Europeans fighting for freedom against despotic regimes. They largely recognised the liberal struggle as a cosmopolitan European one, not as a narrowly German one nor as one that existed in opposition to ‘the West’.

England and France as bastions of progress and civilisation presented models for admiration, emulation, and – occasionally – envy. In the 1830s and ’40s, Hungary’s generation of reform nobles who transformed the country’s social and political life were enamoured by England, as were many German intellectuals. England seemed to represent everything that their countries lacked in terms of national and political life, where the prosperity created by liberal social and political ideas allowed for the full flourishing of national life.

The most difficult question faced by liberal nationalists in ‘non-Western’ countries was not how to redraw borders to make nation and state congruous. It was rather how to reconcile the model provided by France, England or the US with their own circumstances. In other words, how to transform the civic nation from a narrow noble elite to a broader public of educated middle-class men from a confusing collection of linguistically and politically diverse states tied together by the House of Habsburg.

In 1848, a series of revolutions broke out across Europe. Terrified at the sight of disgruntled masses in the streets, European monarchs made once-unthinkable concessions. They called democratically elected assemblies, drafted constitutions and ratified liberal laws. Though by 1850 the revolutions would be defeated – the assemblies closed, constitutions revoked and laws overturned – they had given the middle-class liberal nationalist public its first taste of politics.

The opening of the Frankfurt Parliament in Paulskirche in 1848. Note the portrait of Germania. Courtesy Wikipedia

In 1848, a German National Assembly formed in Frankfurt where revolutionaries produced the first draft constitution for a German nation-state. Hungary, meanwhile, adopted a raft of liberal legislation in spring 1848 that transformed it into a modern parliamentary state. The realisation of the right of ‘historic’ nations like Hungary and Germany (as well as Italy and Poland) to statehood would have meant a de facto partition of central Europe among these four nation-states. Revolutionaries across Europe celebrated the prospect, dismissing the objections of Czechs, Slovaks or Slovenes who would be subsumed in the German or Hungarian nation-states as the cries of ‘unhistoric’ nations or mere ‘fragments of peoples’.

None of these nationalist movements sought to withhold civic rights to members of ethnic minorities. Rather, they expected them to assimilate, as did those minorities who lived in prosperous, progressive Western states. As one deputy asked in the Frankfurt Parliament in 1848: ‘What would the French say if the Breton, Basque and old Ligurian fragments of peoples declared they no longer wanted to be French?’

Deference to the Western nation-state – where the supposedly most advanced ethnic group in the state had become the core of a democratic civic nation – was a common point made in prerevolutionary Hungary as well. The politician Ferenc Pulszky, who himself had travelled extensively in Britain, asked in the 1840s: ‘What do we Hungarians demand of the Slavs[?] … we demand nothing more than what the English ask of the Celtic inhabitants of Wales and high Scotland, nothing more than the French ask of Brittany and Alsace.’ Pulszky could not see why the civic model of nationhood could work for France but not Hungary.

Perhaps 40 per cent of the country spoke Hungarian – not enough to claim that only Hungarian be used in public life

The Western nation-state was a model for some, but a warning for others. From the enslavement of people of African descent and the displacement of native Americans in the US to the suppression of minority languages and dialects in France to the disenfranchisement of Catholics in the UK and the gradual elimination of Celtic languages, Western nationalisms were predicated on the homogenising force of a dominant national group that gave no quarter to national minorities in public life. Unsurprisingly, representatives of national minorities in German states and in Hungary near-universally refused to accept subordinate status in someone else’s nation-state. Or to recognise that the nation-state belonged to groups that were themselves minorities.

Though Bohemia’s elites overwhelmingly spoke German, the majority of Bohemians were Czech speakers. Hungary, meanwhile, was perhaps the most linguistically diverse country in Europe. German dominated its cities, Hungarian the nobility, and Latin served as the official language until 1844. Yet the masses spoke an array of Slavic, Romance, Germanic and Hungarian vernaculars. Only perhaps 40 per cent of the country spoke Hungarian (even by the 1880 census, it was only 46.5 per cent), a plurality but not enough to claim that only Hungarian could be used in public life.

Given the examples set by Western countries, it makes sense that Hungarian nationalists presumed that the predominant national vernacular would be the linguistic rallying point for national development. France, the US and the UK were all home to enormous ethnic, linguistic and racial minorities. But these minorities were either assimilated to the dominant nationality or excluded from national life altogether.

Conversely, there was little reason to expect that nationally conscious Czechs should have accepted that their state was fundamentally German. Or that Hungary’s numerous nationally conscious minorities – Croats with their own subordinate kingdom, Slovaks concentrated heavily in the north, or Romanians who formed majorities in large swathes of Transylvania – should have accepted the conflation of a Magyar ethnic nation with a Hungarian state. In either case, this had little to do with any kind of distinct idea of nationalism but was caused by inherent contradictions in the model of the idealised Western nation-state in a central European context.

Despite such conflicts and contradictions, central European nationalists did not reject the civic nation. The final draft of the revolutionary constitution produced by the Frankfurt Parliament declared in the most straightforward civic terms: ‘The German people consists of the citizens of the states that form the German Empire.’ In 1868, a year after the creation of Austria-Hungary out of a unitary Austrian Empire, the new Hungarian government wrote into the constitution that there would be only a single Hungarian nation. Multiple ‘nationalities’ were also recognised, but there was only a single civic nation. Anyone could be a member, but they had to speak, dress and effectively become a Magyar.

It was an outrage to minority nationalists, but surely no less of an outrage than the national development of Western nation-states. The French Ministry of Public Instruction found in 1863 that at least a quarter of the country spoke no French at all. For the millions of Occitans in the south – whose Romance tongue was at least related to standard French – to Celtic Bretons in the northwest, rebellious Corsicans and totally unique Basques in the southwest, ‘becoming French’ entailed assimilation into a language and culture that was not quite theirs. The congruence of the French ethnic and civic nations was not a result of pure ideas, but of decades – centuries even – of nation-building.

In the latter half of the 19th century, international statisticians were faced with a seemingly intractable question: how could a nation be measured objectively? From the 1850s, a series of conferences had brought together statisticians from across Europe and North America in an attempt to harmonise how countries collected statistics around the world. In 1872, they endorsed the notion that ‘mother tongue’ could determine the boundaries of nationalities. But this was not a universally recognised measure. The following year, the newly founded International Commission on Statistics tasked three Austro-Hungarians with tackling the problem head-on.

The Austro-Hungarians couldn’t agree. One put forward the civic idea of conscious self-identification, another the ethnic idea that it was ‘racial’, and the third simply argued it was a complicated mix that was difficult to measure universally. The tensions between civic and ethnic nationalisms were on full display, but they had little to do with geography. Their range of opinions came at a time in the late 19th century in which ethnic nationalism was increasingly influential across the continent, inspired by the rise of racialist thinking, eugenics and social Darwinism.

By the turn of the 20th century, young radicals across Europe put forth ethnic conceptions of nationhood in which Jews especially were singled out as being a foreign element supposedly unable to be a member of the political community of the nation. But the appearance of antisemitism did not signal a quick triumph among nationalisms with long traditions of Jewish assimilation. In the years up to 1918, the majority of German Jews insisted that they were simply ‘German citizens of the Jewish faith’. Jews in Hungary were no less assimilated. In Austria and Bohemia, most Jews were German-speakers who similarly identified themselves as German.

Kohn was one such German-speaking Jewish Bohemian. He embraced Zionism prior to the First World War, at a time when it was a tiny movement among the elite, and assimilated, Jewish communities of central Europe. After stints in Paris and London, he ended up in Palestine in the mid-1920s hoping to live his Zionist beliefs. After a wave of violent riots broke out there in 1929, Kohn grew disillusioned. The same ‘spirit of extreme nationalism among [Austria-Hungary’s] peoples’ that had made the ‘building of a peaceful multiethnic state’ he saw manifesting itself in Palestine too. He opted to abandon Palestine for the US, where he settled in 1933.

Citizenship cannot force people to feel part of a civic nation

Unlike in the empire of his youth, or the Jewish state of his dreams, in the US Kohn thought he had found a country in which nationalism as a progressive and tolerant force had produced a truly just and liberal society. The contrast between this US reality and the exclusivist ambitions of German, Zionist or Czech nationalists deeply moved the former lawyer-cum-historian. Nationalism, he concluded, was not the problem, but only a certain ‘type’ of non-Western nationalism.

But nationalisms – both Western and non-Western – contain a complicated mixture of civic and ethnic factors, excluding some while offering others the chance for inclusion through assimilation. The state acts as the most powerful force for both. That’s why historians of nationalism like to say states make nations, not the other way around. Nationalism is, by definition, exclusivist insofar as it excludes those who do not think of themselves as a part of the nation. Citizenship cannot force people to feel part of a civic nation, just as citizenship does not stop some from trying to exclude others from their ethnic nation.

Today, it feels vaguely accurate to say that countries like the US, the UK or France base their national identity on the ‘civic’ nationhood of common citizenship. Poland, Hungary, Czechia or even Russia, on the other hand, appear wedded to a more ethnic idea of nationhood rooted in a common language, traditions and myths of origin. It would be an error to read the world of 2024 into the past, as much as it would be an error to read the world of 1944 into the past. An error to assume that today’s ethnic homogeneity in central and eastern European countries, as well as the inclusive nationhoods of Western democracies, are nothing but the consummation of eternal and essential truths rather than the result of contingent historical events. Unfortunately, this was precisely Kohn’s error.

In many ways, Kohn’s The Idea of Nationalism is really a book about a prototype of the Sonderweg (‘special path’) thesis, seeking to explain where German history had ‘gone wrong’ to such an extent that it led to Nazism. Why it did not follow the supposedly inclusive path of other Western countries like France, UK and the US but instead went down a fascist path that culminated in the catastrophe of the Second World War and the Holocaust.

Yet the US of the 1930s that Kohn was so enamoured with was a country whose extremely restrictive immigration policies sought to retain ‘Anglo-Saxon’ ethnic dominance, to which end much of the country mandated racial segregation until the 1960s. With few exceptions, over the past three centuries, the building of all modern nation-states required one ethnic group dominating and assimilating others.

Looking for the ‘roots’ of central and eastern Europe’s lagging behind the West in modernisation, and also at the horror of Nazism, led Kohn to make anachronistic claims about the long-term ethnic continuity and nature of their nations. Civic and ethnic nationalisms were never two distinct courses of historical development taken by different nations, but in fact two different aspects of the development of almost all modern nation-states. The tension between them unfolded across the 19th and 20th centuries as nationalism spread across Europe and the world.