In late 1941, the society pages of American newspapers alighted with news of the newest power couple in Washington, DC: Maxim and Ivy Litvinov. Maxim Litvinov – Stalin’s commissar of foreign affairs in the 1930s – was already known to Americans as the affable Old Bolshevik who’d paved the way for the United States to formally recognise the Soviet Union in 1933. Now he was back in DC as the Soviet Union’s wartime ambassador to the US. This time, his British-born wife Ivy was by his side. Maxim arrived wearing a dirty old suit. Reporters marvelled at the dowdiness of Ivy’s dresses. In the eyes of Americans, the pair’s shabby clothes represented the challenges facing the embattled Soviet Union. East Coast socialites and powerbrokers eagerly welcomed the Litvinovs as ‘exotic’ emissaries of a Soviet reality that, for them, was at once unimaginable and in need of translation. The couple became overnight celebrities as ‘invitations piled up like a snowfall at the embassy’s front door’.

Into this American spotlight stepped Ivy Litvinov, ready to shine in her unofficial diplomatic role as the Soviet ambassador’s wife. She had prepared for this moment in the previous two decades, when her Moscow apartment had served as a receiving room for foreign visitors to the USSR eager for the type of conversation that only Ivy could provide. Known in the West as ‘Madame Litvinoff’, she occupied a unique and precarious position in the Soviet capital. In the Kremlin’s shadow, she had welcomed Anglophone visitors to her table for tea and lively conversation in her native tongue. Madame Litvinoff took on an outsized role in Soviet diplomacy precisely because she could speak fluently to those visitors in their own language. She offered ease of conversation, empathy and witty ripostes to Anglophone guests to the USSR who often entered her living room in a state of culture shock.

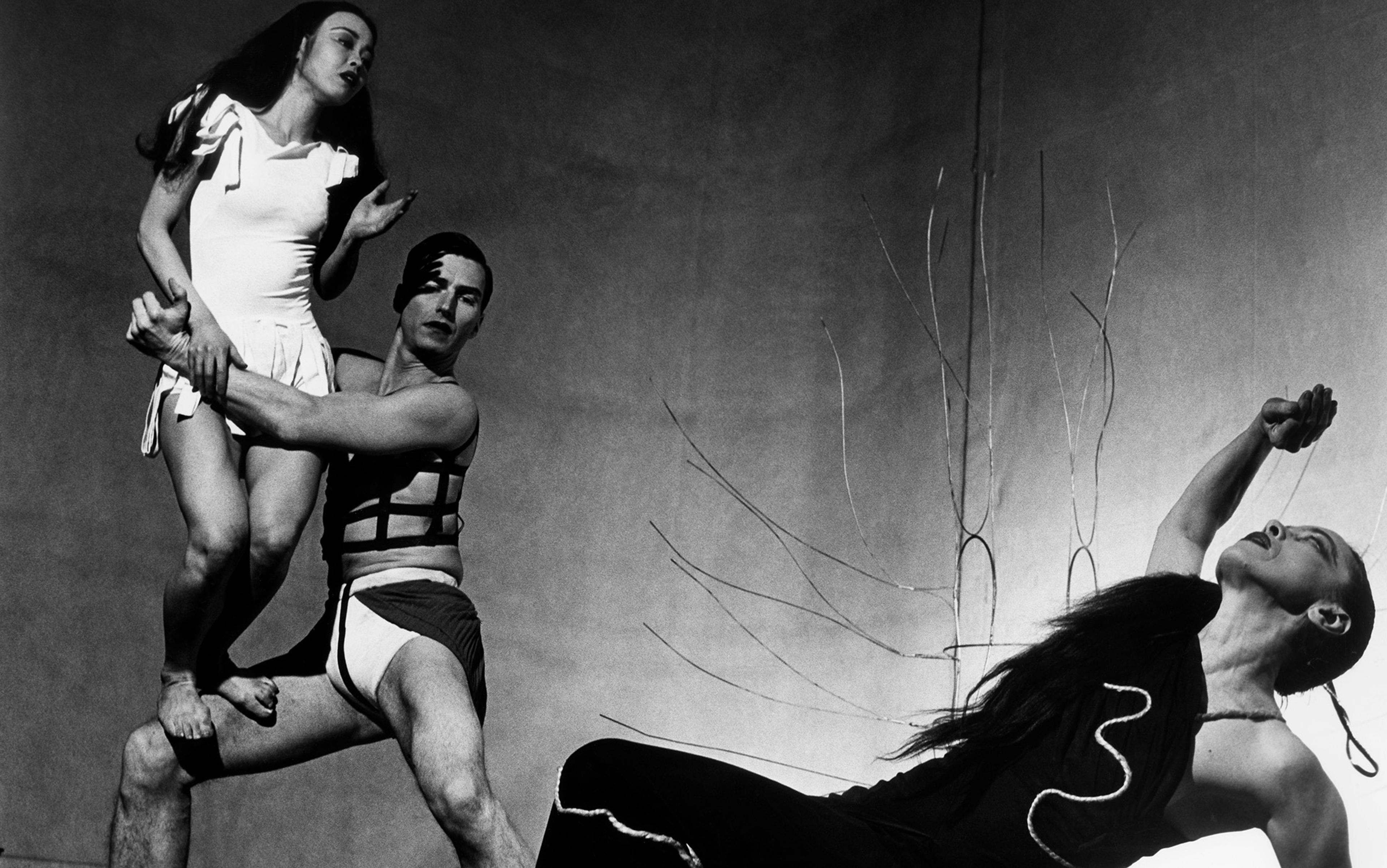

In the US, she was ready not only to reprise her role as the Soviet Union’s English-speaking hostess, but also to chase her full potential as a Hollywood-style celebrity in the land of American capitalism. She set out to make ‘Madame Litvinoff’ a household name. While Maxim tended his ambassadorial duties, Ivy stepped out on the town. She travelled the US, making headlines wherever she went. A self-styled people’s ambassadress, she might have spoken in English on behalf of the Soviet Union, but it was always in her own distinctive voice.

Americans have long since forgotten her. Yet Ivy Litvinov still speaks meaningfully to us today – about women and power, language and diplomacy, and the creative ways that the spouses of prominent politicians have found to assert themselves on the world stage. With her lilting British accent, Madame Litvinoff promoted better relations between the Soviet Union and its Anglophone admirers and critics alike. Dismissed to the margins of history with the insufficient descriptor – ‘British-born wife of Maxim’ – Ivy and her thankless ‘women’s work’ both deserve history’s spotlight.

Ivy and Maxim’s love affair was improbable from the start. The two met in London in 1915. Ivy Low was a modern young woman who had recently published her first two novels and nurtured grand ambitions for her literary career. Maxim Litvinov was a middle-aged Russian Bolshevik living in exile from the tsarist empire. He spoke English clumsily and with a heavy accent. Ivy would later remember Maxim during this time as an absent-minded intellectual whose papers spilled carelessly from the pockets of his ill-fitting clothes. While he debated Marxist theory with comrades, Ivy made no apology for her admitted ‘petit-bourgeois’ outlook and urged him to read the novels of Jane Austen. Maxim handed her a copy of The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism and Capitalism (1928) by George Bernard Shaw, adding the caveat that ‘he doesn’t know much about it, but you know still less’. Ivy and Maxim rambled the English countryside, fell in love, and married in 1916.

Before they exchanged wedding vows, Maxim had warned Ivy that ‘when the drum of revolution calls me I shall follow it, even if it means leaving you.’ For Ivy, socialist revolution in Russia was as unimaginable as the prospect of her and Maxim separating in its wake. She vowed that she’d follow him anywhere.

In 1917, the year of Russia’s revolutions, Ivy found herself caught in a red romance. While she tended to the couple’s growing family – they had a boy and girl – Maxim tended to socialist revolution in his homeland. The promises the couple had once whispered to one another surely now rang in Ivy’s ears. In late 1918, Maxim was sent back from London to Moscow in a prisoner-exchange that the British government negotiated with the new Bolshevik regime.

Ivy and the couple’s two young children joined him in Moscow in 1923. In the Soviet Union, Ivy felt out of place and out of sync with the Bolsheviks’ revolutionary tempo. She spoke few words of Russian and admittedly cared even less to understand the socialist revolution to which her husband had dedicated his life. The British artist Clare Sheridan remarked in surprise upon meeting Ivy that she ‘did not seem to be very political or revolutionary’.

Ivy Litvinov did stick out like a sore thumb among the foreigners who sojourned to the early Soviet Union, and she knew it. She was unrepentantly bourgeois and had travelled to the USSR with one goal in mind: to keep her family together. The socialist revolution to which her husband had devoted his life neither interested nor appealed to her. She shared little in common with the thousands of enthusiastic foreign Leftists who travelled to the Soviet Union in the interwar period intent on helping to build socialism and to ignite worldwide proletarian revolution. As the 20th-century mecca of socialist revolution, Moscow shone as a red beacon of a better world to come, one that would be built by proletarian hands. From Western Europe, North and South America, Asia and the Middle East, socialists travelled to the cosmopolitan headquarters of Bolshevism and brought with them their revolutionary dreams as well as the individual hopes they pinned to the Soviet star that promised to guide them. Many women and men who moved to the Soviet Union in these years did so with the intention of seeing the revolution through to its triumphant conclusion. Some worked as couriers, typists, translators and spies for the Communist International (Comintern). Others took up work in Soviet factories or in the fields of the new collective farms. Some married Soviet citizens and started families. They left behind their old worlds and built new lives for themselves in the Soviet Union.

For any Anglophone dignitary, artist or journalist in the Soviet Union, tea with Madame Litvinoff was de rigueur

In the 1920s and ’30s, scores of other foreigners arrived on Soviet soil as tourists eager to see the revolution with their own eyes. Among the thousands of foreign tourists who travelled to the USSR in these years were fellow travellers who wanted to catch a glimpse of a heroic future that they hoped might one day belong to them too. Yet many sceptics also travelled to the Soviet Union – they wanted to witness firsthand a revolution that ideologically repulsed and frightened them. Businessmen, writers, artists, filmmakers, workers and cultural critics – people from all walks of life arrived in Moscow and Leningrad during these years as tourists to the land of the socialist future.

Ivy Litvinov was thus one of many foreigners trying to make her way in the early Soviet Union. Yet hers was a singular experience of expat life in the USSR. It was only love and marriage – a personal rather than ideological attachment – that had brought her to there. As a newlywed in London, she scarcely could have imagined that her husband would in the 1930s emerge as the top diplomat of the world’s first workers’ state. Ivy’s private papers reveal the profound loneliness she felt once flung into this unexpected Soviet life of hers. Nonetheless, she soon found her feet in her role as the wife of a Soviet ambassador.

For any Anglophone dignitary, celebrity, artist or journalist who visited the Soviet Union in the late 1920s and ’30s, tea with Madame Litvinoff was de rigueur. While Ivy’s charismatic personality charmed most of her Anglophone guests all on its own, there was no underestimating the unexpected joy of entering her home and speaking freely, in the land of the Soviets, with a fellow native-English speaker. The pressure was off. They suddenly felt at home. Ivy soothed them with casual conversation and offered them respite from the bewilderment and estrangement they typically felt in Soviet company, Russian words whizzing over their heads.

The Kremlin relied on Madame Litvinoff to deploy her English in the service of nurturing the Soviet Union’s beneficial relationships with prominent Anglophone visitors. In 1933, the American comedian Harpo Marx arrived in Moscow to entertain Soviets on a goodwill comedy tour. His trip coincided with the announcement of the belated recognition by the US of the Soviet Union – a negotiation brokered by Maxim Litvinov and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Once in Moscow, however, Harpo Marx was overcome with apparent culture shock. His English-speaking Soviet guide was humourless and terse. The food was terrible. The comedian’s efforts to converse with Soviets fell flat. No one was laughing at his jokes. ‘The Russians didn’t understand me and I didn’t understand them,’ Marx later recalled. Frustrated and homesick, he angrily announced that he was calling off his tour. He started packing his bags. Then his phone rang. He heard a mellifluous voice on the line speaking to him in English – finally, a language he could understand. It was Ivy Litvinov, calling to reassure Marx and salvage his goodwill tour. He listened to her and calmed down. By the next morning, his tour in the Soviet Union didn’t seem so hopeless. ‘Suddenly,’ he said, ‘the whole complexion of Russia seemed to change. It didn’t look so grey anymore.’ For the remainder of his journey, he was greeted by rapturous crowds of Soviets who laughed at his routines. In the end, he felt foolish for having wanted to make an abrupt return home to the US.

Emlen Evers was 20 years old when she accompanied her father Joseph Davies to Moscow when he assumed the post of the US ambassador to the Soviet Union in 1937. She didn’t speak Russian – at least not yet – and soon confronted how lonely it could be as a young person living in the American embassy compound in Moscow. Upon first meeting Ivy at the Litvinovs’ apartment, Evers wrote that ‘she appears typically Russian until she speaks in very British English and then one is reminded that she was born in England … She is very gracious and makes one feel at ease immediately.’ Subsequent teas only further endeared Evers to Ivy. ‘It is so nice to be able to speak English,’ she confessed in another diary entry. In a letter home to her mother, Evers wrote of a tiresome tea at the Turkish embassy where she and her hosts attempted to carry out a conversation with the aid of an interpreter. ‘After a half an hour nothing seemed important enough to say,’ Evers sighed. Fulfilling one’s social obligations as the US ambassador’s daughter in Moscow was so much easier and more pleasant at Ivy Litvinov’s. ‘She is English born,’ she explained to her mother, ‘so the language problem was solved.’

While Ivy might have sometimes begrudged her hostess duties on behalf of the Commissariat of Foreign Affairs, she, too, clearly benefited from the role. Even tiresome foreign visitors were known to bring her gifts – desirable consumer goods not easily found in the USSR. In 1934, Vanity Fair celebrated Ivy Litvinov as the ‘unofficial hostess of the Soviet Union’ who ‘befriended many Americans confused by a new regime’. Ivy’s role as Soviet hostess for Anglophone artists, intellectuals and dignitaries gave her the opportunity to fashion herself as a cosmopolitan intellectual in her own right – a budding celebrity on the global arts scene. It enabled her to position herself as an English writer improbably marooned in the Soviet Union. Ivy embraced the curiosity of her position and sought to capitalise on it in the transnational arts scene of the interwar years.

In May 1932, Ivy wrote to Mabel Dodge Luhan – an arts patron in the US whom she had never met in person but whose book she had recently devoured. Ivy sent Luhan one of her own poems. She wrote too of the impossibility of ever visiting Luhan in person to discuss their shared literary interests. ‘I am English myself,’ Ivy explained, ‘but my husband and family are Russian. I can’t come and see you – wish I could, but think I couldn’t ever possibly, because of visas and politics and non-money-for-the-fare. I’ve got to stay in Russia – and like it.’ Ivy urged Luhan to consider a visit to the USSR.

If Ivy was already feeling despondent in 1932 about her diminishing prospects for travel abroad, the remainder of the decade brought only greater worries as each year passed. After 1934, she was no longer permitted to take trips home to England. By mid-decade, Stalinist xenophobia rolled through Moscow like merciless storm clouds. During Stalin’s Terror, the Litvinovs lived in abject fear – especially after Maxim’s humiliating dismissal from the post of commissar of foreign affairs in 1939. In the end, Maxim and Ivy were perhaps more surprised than anyone that they’d managed to survive the late-Stalinist 1930s without suffering arrest or execution. Some have surmised that the couple’s international renown might have been what spared them the fate suffered by many of Maxim’s Old Bolshevik comrades and their families during these dreadful years.

A new life and new possibilities beckoned the Litvinovs at the USSR’s darkest hour. In the wake of the apocalyptic Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, Stalin appointed Maxim as ambassador to the US – a needed ally at a desperate moment for the Soviet Union and the world. Maxim had won over Americans once before – not least with his jovial wit, delivered in English spoken with a thick Russian accent. Fatefully, Maxim and Ivy arrived on US soil on the eve of the Pearl Harbor attack. The Soviet Union and the US eyed one another warily, but came together in an uneasy wartime alliance.

The Litvinovs helped to bolster this alliance immediately upon their arrival. As Life magazine reported in February 1942, the couple was given a lavish welcome reception by Joseph Davies and his heiress wife Marjorie Merriweather Post ‘with Champagne, music, and fanfare’. The party snarled traffic as everybody who was anybody sought entrance to the soon-to-be legendary gala event. ‘All was glamour and gaiety,’ wrote one American reporter, surmising that ‘probably no foreign ambassador ever has been so magnificently greeted’. Maxim and Ivy appeared at ease as they hobnobbed with American powerbrokers and socialites, and the party ensured that they were the talk of the town. Ivy soon sat for interviews and photo sessions. She visited with writers and socialites. Her name was top billing at charity events for Russian War Relief. Americans sent her fan mail.

In 1942, The New York Times claimed that, while Maxim ‘was the man responsible for putting Soviet Russia and the US back on speaking terms again’, it was Ivy who was now ‘winning the friends and influencing a great many people’. She was celebrated as a ‘friendly, intelligent lady’ whose warmth transformed the Soviet embassy in Washington, DC, making it at once ‘fabulous’ and cozy. She was admired for her ‘complete lack of chichi’. Ivy emerged on the Washington scene as a people’s ambassadress – a trusted voice who could speak plainly about Soviet life and translate its realities to the American people. She appealed to Americans with her no-nonsense banter and quick wit. She wasn’t a Bolshevik like her husband, but instead Madame Litvinoff – a brash but winning personality whose honest opinions rolled off her tongue in melodic British English. She was celebrated as ‘a lady who would give a straight answer to a fair question’ – even when she delivered unwelcome criticisms of American life.

At a Hollywood restaurant, she and Harpo Marx drank Champagne in honour of the Soviet victory in Stalingrad

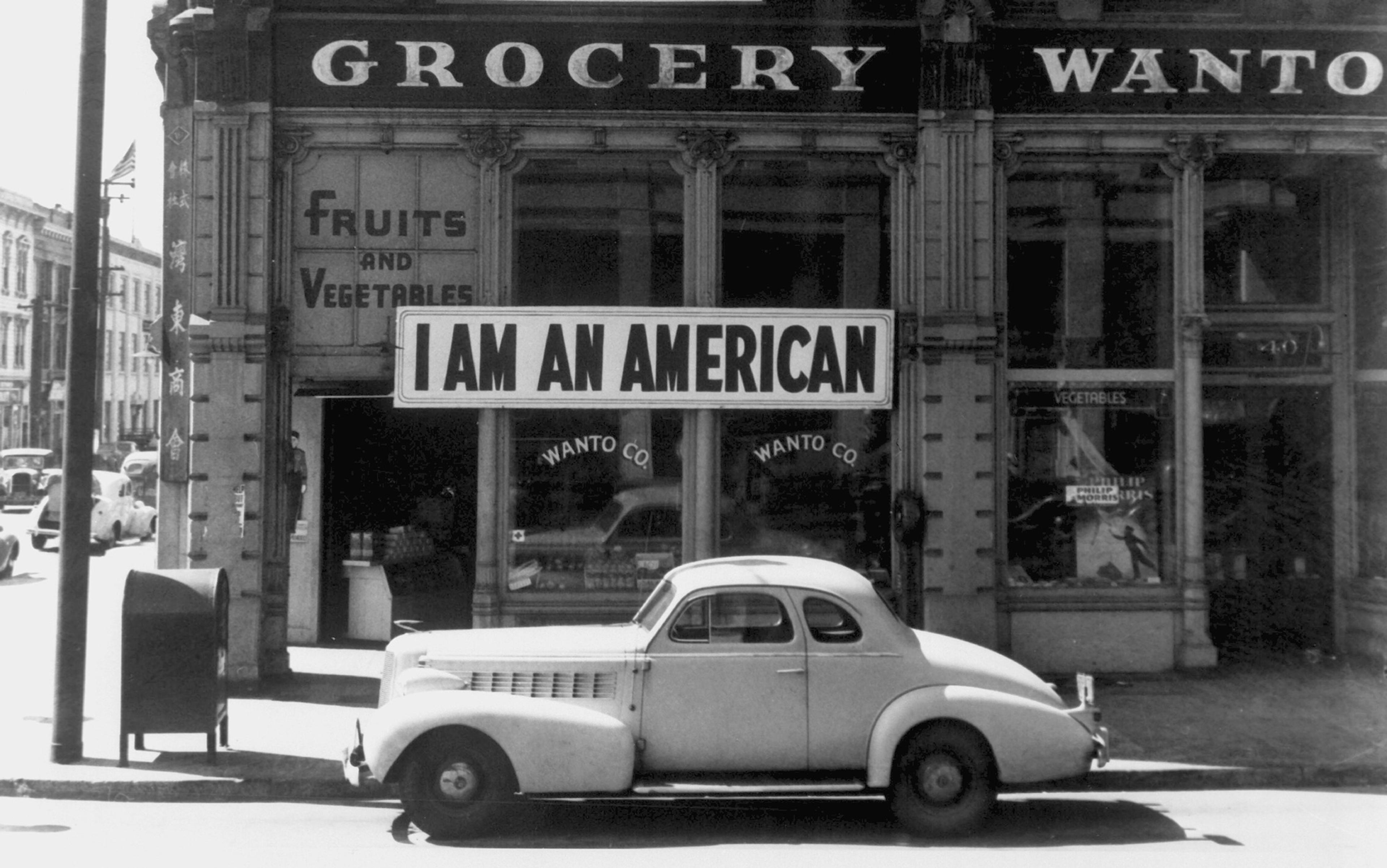

Ivy, for example, spoke openly of American racism, insisting that the Soviet Union offered Americans an edifying example of ‘a successful solution of racial problems’. In Moscow, she explained, there were ‘no segregated districts or schools and the idea of places of entertainment to which certain races could not find access would simply not be understood there.’ Her children, she said, played happily with their classmates who represented the diversity of the multiethnic Soviet Union. ‘I cannot feel that racial minorities in the USA have as yet won the fair treatment which racial minority groups enjoy in the USSR,’ she said. Ivy might have spoken to Americans in their shared language, but she wasn’t going to tell them only what they wanted to hear.

There were times, however, when Ivy Litvinov’s confessed ‘bourgeois’ mindset flamboyantly revealed itself. Her fondness for life in the US was apparent. She lunched fashionably in Manhattan. She travelled to California on the dime of Warner Brothers and shopped the rights to her pulp novel Moscow Mystery with film executives. At a swanky Hollywood restaurant, she and Harpo Marx drank Champagne in honour of the Soviet victory in Stalingrad.

Her American dream soon shattered. In August 1943, Moscow announced that Maxim was removed from his post as ambassador to the US. Although he returned to the USSR, Ivy stayed behind for several months to conduct her own private farewell tour. When she departed the US in November 1943, she recited for reporters a laundry list of the American consumer goods she was eager to deliver into the hands of her family: vitamins, cigars, books and a ‘toy American tank for her grandson’. When pressed to discuss diplomatic relations, Ivy generalised that ‘I think America and Russia should be nearer and nearer as time goes on.’ When asked if she’d miss anything about the US or its ‘political philosophy’, Ivy replied that she would miss ‘the gadgets’.

Ivy’s sadness at saying goodbye to her life in the US was difficult to disguise. In returning to the Soviet Union, she was returning to a certain loneliness she’d known for decades as an oddly positioned Soviet outsider living in the Kremlin’s shadow. She was going to miss much more than American consumer goods. In a letter to a close friend, she wrote despairingly of her imminent departure from the US: ‘It is the end of life for me, of English talk, English books, English writing.’

Privately, Ivy’s sadness at departing the US went still deeper. While living in Washington, DC, she and Maxim had considered defecting to the US. Yet abandoning the Soviet Union would have meant abandoning their children and grandchildren too. Faced with this impossible choice, the Litvinovs returned to the devastated Soviet Union and attempted to rebuild their lives there.

After the war, Maxim was shuffled into a quiet retirement, again cast aside by the Kremlin. He was officially dismissed from his last post in 1946, leaving Western observers to mourn his departure from the diplomatic scene. ‘The world will miss Maxim Litvinoff,’ one American newspaper opined. ‘It will miss not only the friends he made for Russia, but also the temperate and compromising influence he always strove to exert on his diplomatic colleagues.’ Though it went unremarked in the Western press, Maxim’s retirement meant that Ivy, too, had been retired from her unofficial role as the Soviet Union’s English-speaking hostess. She, too, had made many friends for the USSR. She, too, was cast aside.

Maxim died in late 1951. After her husband’s death, Ivy’s world in Moscow narrowed considerably. On occasion, she still received Western visitors whom she’d first invited into her Moscow home decades before, at the height of Maxim’s diplomatic career. In the 1960s, she began writing short stories, many of which were published in her favourite American publication, The New Yorker. She cultivated a deep friendship with her editor at the magazine, Rachel MacKenzie, as the two women traded professional and personal news in letters that travelled across the Iron Curtain. In their correspondence, an ageing Ivy frequently begged for more letters – from MacKenzie and from her American friends from the olden days. By the early 1970s, Ivy’s longtime friends in the West sensed in her missives a worsening isolation, a desperation to connect with those who spoke her language. Ivy thrilled at epistolary exchange and despaired at an empty mailbox. She yearned for news from friends abroad – people who felt to her a world away, a world that had once been her own.

Only in 1972, at the age of 83, did Ivy Litvinov make a return home to England for good. She left behind her Soviet life, taking with her suitcases stuffed with her personal papers and manuscript drafts. She had returned at last to her own homeland – to the life of ‘English talk, English books, English writing’ for which she’d longed for so many years. Hers was a quiet retirement, one spent largely in a modest apartment in the English seaside town of Hove. She died of complications of a heart attack in April 1977.

When Stalin’s Soviet Union most needed to be able to find a common language with the Anglophone West, it time and again turned – somewhat warily, no doubt – to Ivy Litvinov. As the Soviet Union’s unofficial English-speaking hostess, she served tea, cracked jokes and frequently revealed her own bourgeois sensibilities. During the Second World War, she charmed Americans, symbolising for them the possibility of friendlier relations with the Soviet Union. With her disarming personality and unmistakable British accent, Madame Litvinoff humanised the USSR and reassured her English-speaking guests and audiences. Her husband Maxim is rightly remembered as one of the most consequential diplomats of the 20th century. Yet Ivy Litvinov also played a diplomatic role of considerable significance – one that has been too easily forgotten, dismissed as mere ‘women’s work’.