In October 2012, the Colombian government sat down to peace talks with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) — among the last of Latin America’s left-wing guerrilla armies. Hopes were high that an end to a conflict that has raged for close to 50 years might be at hand. Colombians, weary of decades of violence, are growing impatient for results.

Following the end of the Cuban Revolution in 1959, every country in South America saw at least one rebel army spring up within its borders. But when the USSR collapsed in 1991, Soviet funding for the world’s revolutionary socialists dried up, and most of Latin America’s guerrilla armies had to return to civilian life. Not the Colombians. Until recently, the FARC were the biggest guerrilla army in the world, and controlled around a third of Colombia’s land area. As recently as 2001 they came close to overrunning the capital, Bogotá. So why have the FARC lasted as long as they have?

To most outsiders, Colombia is the epitome of festering, futile conflict. Until recently, Colombia had more internally displaced civilians, printed more fake dollars, exported more prostitutes, armed more children, had more landmine victims, and processed more cocaine than any other country in the Americas (and in some of those categories, in the world). While it might be hard to spot the idealism in all this, after 13 years of musing on Colombia, I’m convinced that the inability to square rhetoric with reality is at the root of the longest running internal conflict in the world.

Rhetoric — the art of using speech to persuade, influence or please — is highly prized in Colombia. It is a country where university students sell their poems on buses, a country that has more singer-songwriters than any other I have ever been to. Its newspapers are remarkable for their scarcity of reporters — most of whom would probably get shot if they did their jobs properly — and their preponderance of commentators, pundits and experts. Such is the respect paid to rhetoricians in Colombia that anyone with a university education and an opinion is deemed worthy of the title ‘doctor’.

This love of rhetoric means that Colombia is a country with a plethora of academics, spokesmen and politicians, all trying to outdo one another with their high-mindedness. The bookshops of Bogotá stock hundreds of books analysing the armed conflict. Although these books are studiously ignored by all the parties to the fighting, they lend an air of authority to the country’s hidebound education system.

It’s hard to believe that the FARC started out as modest, peace-loving smallholders who just wanted to be left alone to farm their plots

Lawyers, another breed of rhetorician, are also thick on the ground in Colombia, notwithstanding the fact that the legal system is notoriously slow, ineffectual and corrupt. As a result, Colombian prisons are full of people who are still waiting to go to trial. Meanwhile most crimes, however heinous, go unpunished.

I have talked to many victims of the conflict since I started travelling to Colombia in 1999. In a country that combines verbosity with indifference to the suffering of others, it should be no surprise that so many of them called for una vida digna, a dignified life. The FARC are past masters at rhetorical posturing. Here’s what they posted on their website after the death of one of their senior comandantes in 2010:

It is with profound remorse, clenched fists and chests heavy with feeling that we inform the people of Colombia and our brothers in Latin America that Commander Jorge Briceño, our brave, proud hero of a thousand battles, commander since the glorious days of the foundation of the FARC, has fallen at his post, at his men’s side, while fulfilling his revolutionary duties, following a cowardly bombardment akin to the Nazi blitzkrieg.

Reading such hyperbole, it’s hard to believe that the FARC started out as modest, peace-loving smallholders who just wanted to be left alone to farm their plots. With origins as the military arm of the Colombian Communist Party, the FARC see themselves as the representatives of Colombia’s poor agricultural labouring classes, the campesinos.

Bands of poor, usually landless campesino labourers had been draining swamps and clearing jungle since the days when Colombia was ruled from Madrid. In the early days of the FARC, after the extreme violence of the 1950s and early ‘60s, large numbers of campesinos found themselves on virgin land once again, living in tin shacks miles from anywhere, where there had never been schools or hospitals, much less police stations or army barracks. The guerrillas organised road-building crews, parcelled out land, and provided much needed law enforcement.

Anyone hoping that the government and guerrillas will sign a conclusive peace treaty this year would do well to listen to the songs of FARC troubadours such as Julián Conrado. They are testament to the alliance forged by guerrillas and campesinos in those early days. Battered as it is, this alliance endures, at least in some far-flung corners of the countryside, to this day. To some listeners, Conrado’s voice sounds defiant, proud, and resolute. Others, such as the thousands of Colombians who marched against the FARC in the 2008 protests, only hear piety, self-pity and bluster.

By the time the latest round of peace talks between the FARC and the Colombian government got underway in 2012, Venezuela, Ecuador and Brazil each had a democratically elected, left-leaning government. When even the late Hugo Chávez, the most radical Latin American president of recent times, tells the FARC that the armed struggle is over, it’s hard to escape the feeling that its brand of revolutionary politics is an anachronism.

But if the FARC are indeed ‘walking ghosts’, as the American journalist Steven Dudley calls them, that’s not how they see things. Rather than relics of a discredited tradition of vanguardist radicalism, they regard themselves as akin to the early Christian martyrs, driven into the wilderness by the Romans in Bogotá. Deluded they might well be, but the guerrillas have made a virtue of their isolation — and, thanks to the cocaine trade, they’ve also made a business out of it. The romance of revolution isn’t dead yet.

La Macarena is a small jungle settlement, about 170 miles due south of Bogotá. Until the army took control of the town in 2005, it was controlled by the FARC. In the town’s church was a mural, painted over soon after the guerrillas were forced out, that depicted Jesus sitting with his 12 disciples. Or at least, that’s who they looked to be at first glance; on closer inspection, they turned out to be members of the FARC high command. Their expressions — devout and pained — were fitting enough, though the combat fatigues gave them away.

David Hutchinson, a British banker who spent the best part of a year as a captive of the FARC, told me that he often heard his young guards saying their prayers after lights out. One read: ‘Dear Che in heaven, who is watching over me, how I love you Che, may I follow your example.’

For many campesinos, the FARC’s communism is of a kind with that of Jesus Christ, another friend of the poor who endured all that the rich and powerful could throw at him. The iconography of the revolutionary left in Latin America often verges on a mystical reverence for Che-Jesus, with the splendour and mystery of the continent’s mountains and jungles standing in for paradise.

‘They live together in a camp, and they play practical jokes and go fishing and sing, and they have a very active sex life. And by the age of 25 they’re all dead’

Critics of the FARC say that the growing proportion of teenagers in their ranks is evidence of their desperation, as well as their callous disregard for children’s rights. The FARC counter that their youngest recruits are often orphans, or have been abused. Without the guerrillas, they argue, many would drift into gangs, drug trafficking, or the remnants of the paramilitaries.

What neither side likes to admit is that teenagers are drawn to the FARC’s rhetoric because it is based on familiar Christian tenets of deliverance from evil, redemption from a life of sin, and the promise of a return to a state of innocence. Something similar can be seen in Mexico, where the cult of Santa Muerte — Holy Death — draws on the rituals of Catholicism to adorn a religion centred not on the virtuous life, but on the power of fate. Santa Muerte is popular wherever the pull of criminal circles is strong. In Colombia too, the poverty, danger and general precariousness of daily life has only strengthened popular religiosity.

Most of the FARC’s young recruits learn how to handle a gun before they learn how to read or write; their religion, like their politics, has to be straightforward, simple and purgative. What Christianity and communism have in common, at least in their Colombian forms, is a glorious, transcendental end. Keep that in mind, and the young recruit can explain away all manner of venal means, which is how one man’s narco-terrorist can be another’s liberator of the people.

I asked David Hutchinson why he thought young people joined the FARC. ‘They get given a uniform, cigarettes, food and a rifle,’ he told me. ‘And companionship. It’s all rather boy-scoutish. They live together in a camp, and they play practical jokes and go fishing and sing, and they have a very active sex life. And by the age of 25 they’re usually all dead. It’s pretty pathetic.’

When the first representatives of the Cali cartel came down the river Caquetá in 1988, offering coca seeds to any campesino who would take them, and promising to pay good prices come harvest time, the FARC were intensely wary. Isolated as they were, even the comandantes knew about the harm crack cocaine was doing to Americans.

But the campesinos, whose guardians the FARC claim to be, were broke and the cocaine business was lucrative. So the guerrillas, ever pragmatic, came to an accommodation with the new arrivals. They would tax the growers, just like they taxed the smugglers and the legitimate businesses operating in areas under their control. They were confident that their ideological purity would resist any threat of contamination by the drugs business.

When I was in Colombia in 2011, I spoke to two former guerrillas about the impact the business had had on the FARC. Nicolas had joined up in 1991, just as the rest of the world was celebrating the collapse of communism. He’d spent 13 years in Sumapaz, the huge highland moors to the south west of Bogotá, where he had worked on a land reform programme that the guerrillas had forced upon one of the area’s big landowners.

Over time, Nicolas told me, the FARC’s cautious coexistence with the cocaine trade turned into something more like symbiosis. As the Americans ramped up their war on drugs in the mid-’90s, Colombia’s traffickers needed better protection for their laboratories and smuggling corridors. At the same time, the FARC were more convinced than ever that the détente between Colombia’s drugs traffickers, the army and the paramilitaries made a peaceful road to socialism impossible. The guerrillas would have to take power by force of arms. They needed money for weapons; the cocaine business was awash with money.

‘With the drugs came a lot more money,’ Nicolas told me, ‘but that created a lot of false needs. When I first joined up, the FARC was a guerrilla army for the people, but not everyone was in uniform and not everyone was armed. But as the local commanders got richer, they were just thinking about how to get the next piece of sophisticated weaponry. In time, the organisation became completely militarised.’

‘The comandantes used to be happy to have a watch,’ Nicholas continued. ‘Now they wanted one with 150 memories, and a calendar for I don’t know what. The idea of taking their programme to the people — organising them to take collective action in defence of their interests, or building the roads and schools that they needed — all that went out of the window. Capitalism infiltrated socialism.’

These days, the FARC’s enemies say that they are no more than criminals, competing with former paramilitaries for control of the cocaine business. As well as drug running, the guerrillas are accused of the violent displacement of uncooperative communities, the widespread use of landmines, and the kidnap of thousands of innocent people for ransom.

Latin American leftists believed that all they needed to overturn the established order was a mad voluntarism — the idea that with a spirited challenge to the oligarchy, a handful of men in the hills might sweep to power

In the process of amassing power, the ‘army of the people’ have lost much of their former popularity. Perhaps the older comandantes, veterans of the long struggle to build a popular political alternative in the Colombian countryside, still have faith in the FARC’s revolutionary project. But most of the rank and file are united only by a desire to escape poverty, or avenge the death of a relative killed by the army. To the extent that they have an ideological commitment, it is to defend an inherited cause, mouthed without conviction by those afraid to challenge their superiors. But even that retains a power that is hard for outsiders to understand.

Most commentators blame the longevity of the FARC on the drugs trade, arguing that without the revenue from producing and trafficking cocaine, the guerrillas would have had to sue for peace long ago. Others point out that Colombia is still one of the most unequal countries on the planet. More than half the land (52.2 per cent) is owned by just 1.15 per cent of the population, according to a UN Development Program report from 2011. More than 40 per cent of Colombians live in absolute poverty. Some blame the FARC’s existence on the brutality of the Colombian army and its erstwhile paramilitary allies — with or without the cocaine business, they seem to suggest, Colombia is so riddled with iniquity that an armed insurgency is practically inevitable.

This is all true, but there is more to it than practicality and economics. In 2012, shortly before his death, the British Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm reflected on the failure of the revolutionary left to seize power in Latin America. He pointed out that after Fidel Castro had defeated the Cuban army with relative ease, generations of Latin American leftists believed that all they needed to overturn the established order was a mad voluntarism — the idea that with a spirited challenge to the oligarchy, a handful of men in the hills might sweep to power. This was as seductive as it was mistaken.

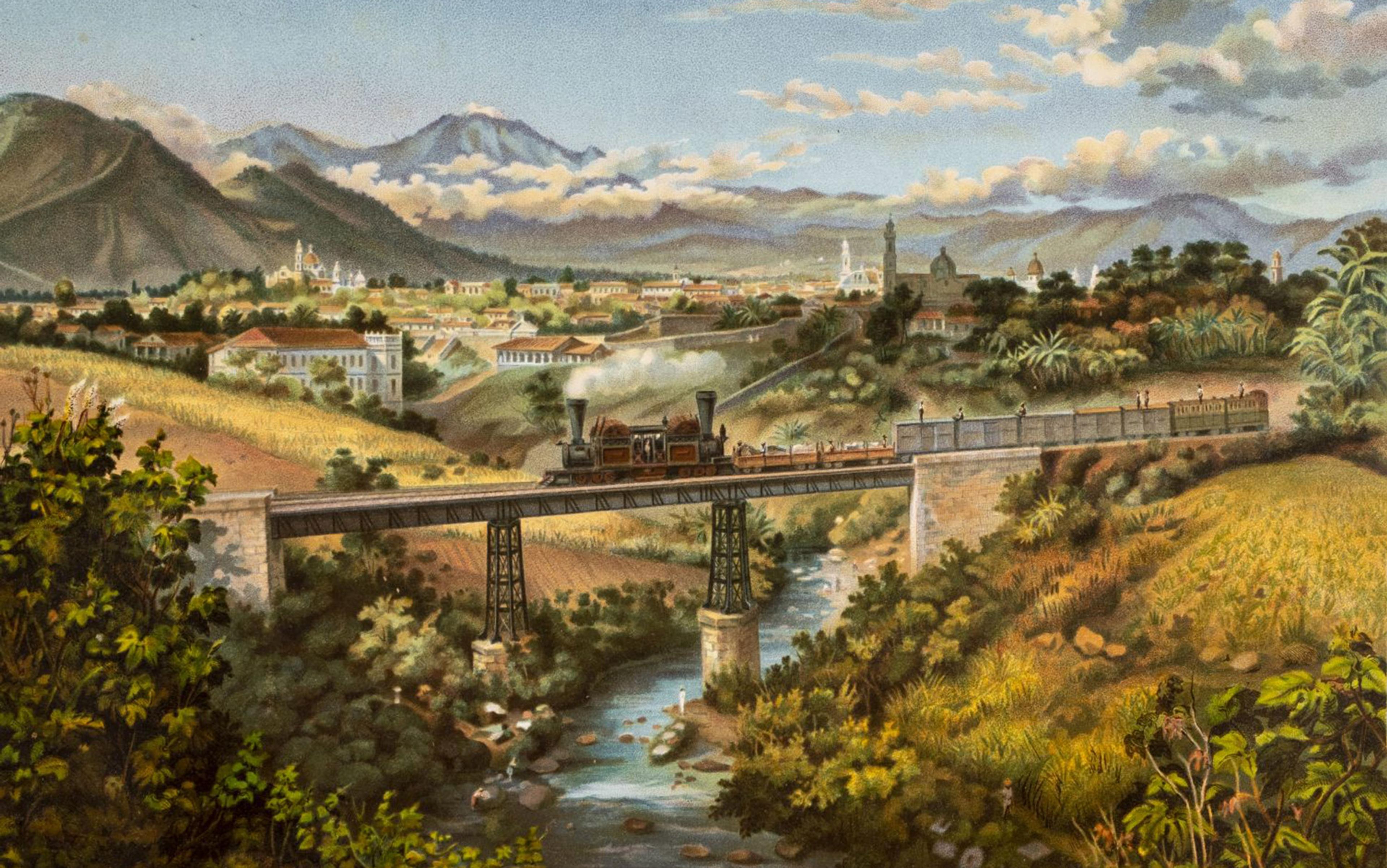

The mad voluntarism of Latin America’s guerrilla armies goes to the heart of the conflict in Colombia. Not that such idealistic wilfulness is confined to leftists: Colombia has long been yanked this way and that by ideologues from the right, as well as the left. Shortly before his death in 1829, Simón Bolívar warned that without an external enemy to unite the country, Colombians were doomed to perpetual civil war. He was proved right: civil wars consumed the passions of rich and poor Colombians alike for the best part of the 19th century.

These wars had multiple drivers, but soaring idealism, base intolerance of other people’s ideals, and a readiness to take up arms were recurring themes. To defend the Catholic Church’s monopoly over their children’s education, Conservatives were prepared to slaughter the menfolk of entire villages. In the name of free trade and federalism, Liberals burned down farms and killed policemen by the score. At the University of Bogotá, riots even broke out over the utilitarian, anti-clerical teachings of the philosopher Jeremy Bentham, who Catholics blamed for an earthquake that struck the city in 1826.

So it was that in the name of various, little-understood foreigners (God being one of them), a tiny elite of semi-educated landowners mobilised thousands of their impoverished farmhands, draining the Treasury of what little money it had and laying waste to some of the best farmland in the Americas. The death toll of La Violencia, the period between 1948 and 1958 during which the Liberals and the Communists fought the Conservatives (and each other) in a bloody civil war, was around 300,000, mostly peasants.

In other Latin American countries riven by sectarian conflicts in the years after independence, one side or other eventually won out. But Colombia’s Liberals and Conservatives were mostly evenly matched in terms of money and manpower. With victory seemingly always at hand, peace was only ever a chance to rest and rearm before the inevitable return to the fray. Violence became a way of life, ingrained into employment practises and land ownership, and sustained by the church, the press and the universities. If the ideals of Liberalism and Conservatism lent dignity to the struggle, the reality of perpetual war stripped it away.

Little wonder that Colombia is full of empty symbolism, and young men in the poverty-stricken countryside can still be stirred by FARC recruiters. The national anthem blares out on TV, interspersed with endless advertisements celebrating the valour of the armed forces in their daily struggle with the terrorists. Of the thousands of murders recorded in the capital in the past three years, only a third of cases had a defendant brought to trial, let alone prosecuted. Despite such awful police work, the flag outside the national police academy on the Avenida El Dorado must be the size of half a football field.

Formally, the constitution and the laws it frames address many of the problems that drive the conflict. But the formal face of Colombia is like a doll’s house — a pristine replica of a much larger building that has long been abandoned to the elements. The truth is that, behind the façade of legalism, Colombia’s laws carry little weight on the ground. The rhetoric of the war on terror taps into a long tradition of highfalutin bluster, but talk is cheap. Building institutions and enforcing laws, on the other hand, is going to be expensive.

Both sides in the Colombian conflict carry a great deal of suspicion, bitterness and resentment. As Nelson Mandela once said: resentment is like drinking poison and then hoping it will kill your enemies. If Colombia’s guerrillas are to renounce violence for good, both they and the Colombian government have to drop the rhetoric of war, with its insistence on total domination and enforced forgetting of past crimes. Only then can some dignity be restored to the political life of Colombia. It is not only arms that must be laid down, but the grand and tattered words of revolution.