Several years ago, I inherited a cache of papers from my grandfather, Zoltán. He escaped from Sátoraljaújhely, a small town in northeastern Hungary, in December 1937. After arriving in Cleveland, Ohio, he began corresponding with his parents, sister, brother and friends who had remained behind. The letters run through to the end of 1943. In January 1945, after a year of silence from his family, he sent a telegram: ‘anxious to hear about you and about all relatives. How could we assist you?’ He was unaware that they had been deported to Auschwitz. None survived.

Reading the correspondence, I couldn’t help but think about the deportation that occurred near my current home in Athens, Georgia, a little more than a century earlier. In May 1830, the United States Congress passed ‘an Act to provide for an exchange of lands with the Indians’, authorising the US federal government to uproot and transport 80,000 people from their homes east of the Mississippi. By river and road, the federal government intended to deport them to a newly segregated region called ‘Indian Territory’, land that would be absorbed later into the states of Oklahoma and Kansas. Some of the main streets in Athens, Georgia – Lumpkin, Clayton, Dearing – bear the names of local figures who played significant roles in this earlier deportation, known today as ‘Indian Removal’.

The 80,000 victims of this state-sponsored forced relocation make up only a fraction of the hundreds of thousands of Indigenous Americans dispossessed since Europeans arrived in the Americas. But they represent nearly the entire native population then remaining in the US, excluding the nation’s unorganised western territories. By the end of the decade-long operation, only a few thousand Native Americans remained east of the Mississippi. The federal government deported the Choctaws, Chickasaws, Creeks, Cherokees and Seminoles from the country’s South, and the Delawares, Miamis, Odawas, Shawnees, Wyandots, Potawatomis and others from the North. In 1838, one recent immigrant to the Choctaws’ and Chickasaws’ Mississippi homelands rejoiced that ‘An Indian is now a rare sight.’ The secretary of war Lewis Cass celebrated that it was now possible to draw a line down the continent. ‘Indians’ lived on one side, he said, ‘our citizens’ on the other.

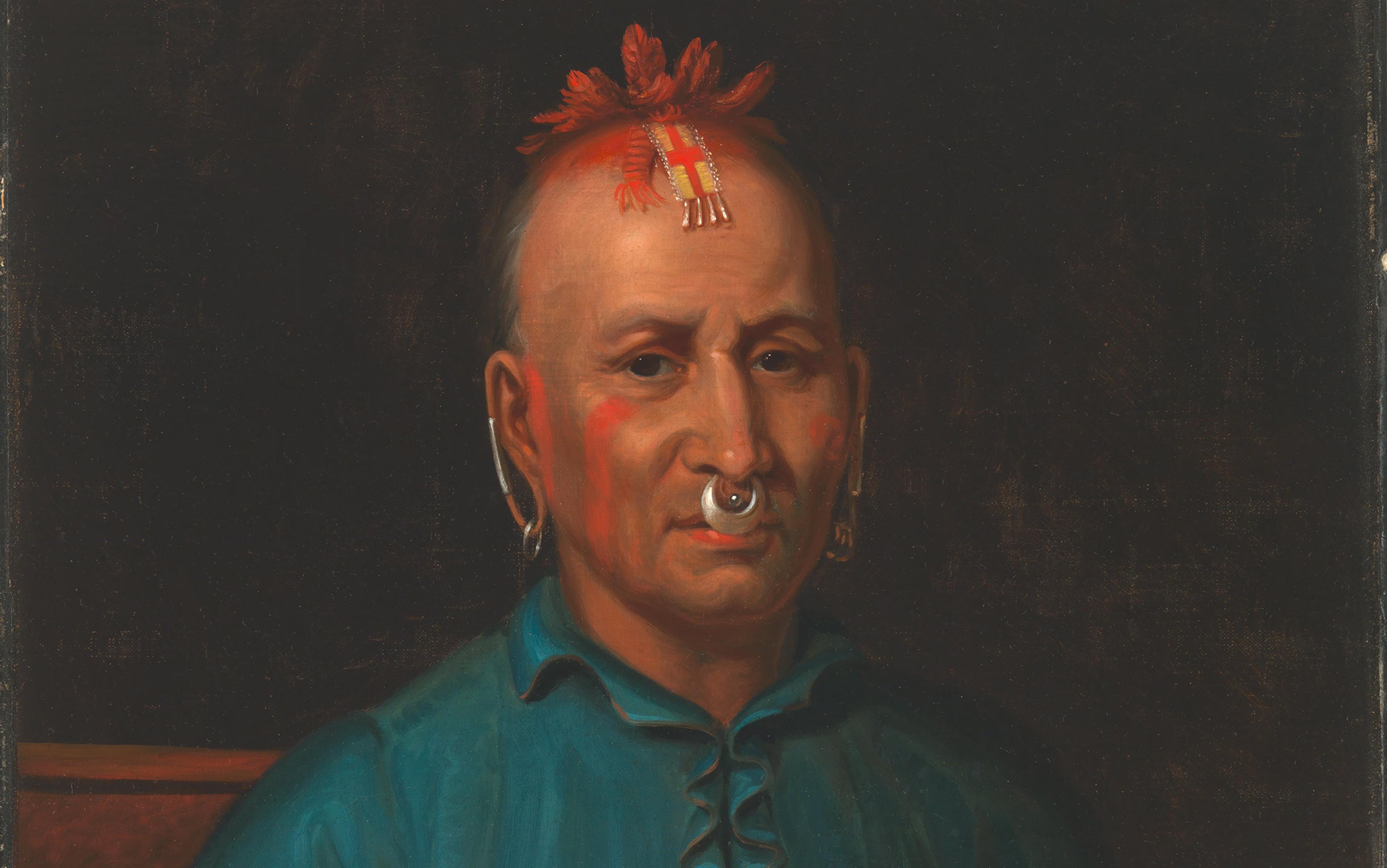

The Trail Of Tears (1942) by Robert Lindeux. Courtesy the Woolaroc Museum, Bartlesville, Oklahoma/Granger Collection/Shutterstock.

The Nazi deportation of Jews in the 1940s and the US deportation of Native Americans in the 1830s cannot be equated. The differences, both in scale and intent, are so immense that they scarcely need to be pointed out. Suffice to say that there were no industrialised death camps in the 1830s, and that some Indigenous Americans, fully informed of the risks, truly believed that it was in their best interest to accede to US demands that they move.

Nonetheless, though the Nazi death camps appear to be unfathomable and incomparable, state-sponsored forced migrations share a genealogy. The Final Solution ultimately took on a horrific form all of its own, yet the steps leading up to it covered familiar ground. State administrators widely believed that it was good policy to move problem peoples, whom they deemed backward or incapable of modernising, to remote colonies. That is why Franklin Roosevelt’s advisor on refugee policy, Isaiah Bowman, declared that the resettlement of Jews fleeing Nazi Germany ought to be understood as ‘a broad scientific undertaking, humanitarian in purpose’. Pioneering, as Bowman called it, would resolve territorial conflict to everyone’s benefit. It is also why Wilson Lumpkin, one of the lead architects of the US plan to deport native peoples in the 1830s, asserted that the ‘Indians can never be happy and prosperous’ in their homelands. Only if they were moved elsewhere would ‘a happy destiny’ await them.

While the US campaign of the 1830s is part of the violent history of European colonialism in the Americas, it also belongs to the history of state-sponsored forced migrations. This history began at least 2,800 years ago, when the neo-Assyrian empire expelled conquered peoples and annexed their lands. The list of perpetrators includes Byzantine rulers, Iranian shahs, the English crown and Qing emperors. In fact, state-sponsored mass deportations are so common historically as to be forgettable. Who remembers that Alfonso III sold the entire population of Minorca, perhaps some 40,000 people, into slavery in 1287?

And yet not all deportations are the same. Beginning in the 19th century, ambitious state administrators around the world, driven by nationalist fervour and racist ideology, began to focus on remaking their citizenry. They employed bureaucratic tools of state administration such as censuses to create unified and homogeneous citizens: Greece for the Greeks, Turkey for the Turks, and so on. Indian Removal, understood in this context, is among the first mass deportations in the modern world.

In Europe, victims of deportations shifted along with the national borders, but Jews, the eternal outsiders, remained a consistent problem for state administrators. Their unusual status gave rise to the ‘Jewish Question’, first posed as a policy matter by Russia when it invaded Poland in the late-18th century, though European states had been targeting Jews for nearly 2,000 years. The US version was the ‘Indian Question’, a phrase launched into wide circulation in the 1820s. Indians and Jews were alike, wrote one Georgian in 1825, ‘a kind of citizens of an inferior order’. They were ‘united to society’, he explained, ‘without participating in all of its advantages’. According to some learned scholars at the time, Native Americans didn’t just resemble Jews; as purported descendants of the lost tribes of Israel, they were Jews. (Both peoples use lunar calendars, abstain from unclean things, practise sacrifices and fasts, and so on.) What was to be done with these wayward members of the tribe, who lived within the boundaries of the US but didn’t belong? The ‘Indian Question’ invited paternalistic measures at best, expulsion or extermination at worst.

After thousands of cranial measurements, he concluded that Native Americans were ‘averse to cultivation’

Like the ‘Jewish Question’, the ‘Indian Question’ animated some of the finest minds in the nation. The ‘best and brightest’ of 19th-century American intellectuals, informed by the science of race then emerging in Europe, produced substantial works that lent US policy a veneer of scientific legitimacy. They exhibited a morbid and particular fascination with physical differences between humans. During the decade of deportation, grave robbers fanned out across Indian country to dig up and decapitate freshly buried bodies or, less laboriously, to behead the casualties of war. After boiling off the decaying flesh, they boxed up the crania and sent them to East Coast scientists for analysis. One aged Creek man, living in present-day Alabama in 1836, told a US officer ‘with great bitterness’ that he refused to give up his land. He would ‘stay and die here’, he asserted, ‘and then the whites might have his skull for a water cup’. This was no fantasy. A phrenologist had visited the Creeks a few months before and disinterred and carried off a number of skulls.

Many of these crania converged on the laboratory of Samuel George Morton, a medical doctor in Philadelphia who would become renowned as the founder of American physical anthropology. Morton spent the 1830s studying the crania that his associates had procured. One ‘interesting relic’ from the Seminole Nation presented ‘a lofty, though retreating forehead, great breadth between the parietal bones, and remarkable altitude of the whole cranium’. Four other skulls from the Cherokee Nation were all small in volume. After taking thousands of measurements, Morton reached a predictable conclusion: Native Americans were ‘averse to cultivation and slow in acquiring knowledge; restless, revengeful, and fond of war, and wholly destitute of maritime adventure.’

Policymakers rested their unflattering assessments of native peoples atop such inaccurate and meaningless phrenological measurements. According to Secretary of War Lewis Cass, who presided over several years of deportations in the 1830s, Native Americans were improvident, habitually indolent, ‘implacable in their resentments’, fatalistic and ‘an anomaly upon the face of the earth’. Cass published these insights in the highbrow North American Review, and scores of local newspapers reprinted them. The propaganda helped to justify the massive undertaking to rid the states of native peoples.

Racism had structured relationships between native and non-native peoples since the onset of colonisation, but now Western medicine was steering state policy down a particularly sinister path. Moreover, for the first time in North America, dispossession would unfold under the auspices of a bureaucracy. Except where it failed, the deportation of the 1830s was an administrative affair, directed by self-proclaimed experts, who formulated government policy with attention to the latest and best information, and who strove to implement their plans with executive authority and efficiency. Under the direction of George Gibson, the punctilious and tireless commissary general of subsistence, a small army of clerks toiled in an undistinguished office building west of the White House, copying letters, filling out ledgers, and tri-folding papers in a coordinated effort to keep the deportations in motion.

The US federal government was then a diminutive organisation compared with its European counterparts. It was even smaller relative to the massive states and bureaucracies that would oversee the deportations of the 20th century. Washington City, as the US capital was then known, existed mostly in the imagination. ‘Its seven theoretical avenues may be traced,’ scoffed a British tourist, ‘but all except Pennsylvania Avenue are bare and forlorn.’ Only ‘a few mean houses’, the sheds of the navy yard, and three or four ‘villas’ relieved the eye ‘in this space intended to be so busy and magnificent’. Some 600 federal employees worked in the city. The entire government employed fewer than 11,000 individuals, of whom 8,000 delivered the mail and were of little use in deporting families. The armed forces, responsible for guarding a 1,500-mile western frontier and a 2,500-mile coastline, barely surpassed 11,000 men.

Nonetheless, Washington City’s empty fields didn’t breed humility, and the paperwork produced by the small but determined bureaucracy mounted with the number of victims. Clerks recorded the names of the heads of every single family that the US deported, how many rations they received during transportation, who survived the ordeal, who did not, and when they died. In some case, assessors listed and valued their personal property (one wagon, one fiddle, a bay horse, three peach trees, and so on). The muster roll that kept track of the deportees, explained Gibson, was ‘the very point upon which hinges the whole system’. The commissary general fixated on reducing expenses and scoured accounts for errors, even calculating to the 10th of a penny when necessary. ‘Wherever money is expended by you,’ he instructed one field agent, ‘the greatest practicable exactitude will be expected.’

The remains of this clerical output, housed in the National Archives in Washington, consist of digests, docket books, ledgers, schedules, reports, papers, abstracts and journals, some fastened in giant leatherbound volumes, others stashed looseleaf in boxes. The scale of the federal operation can perhaps be grasped by estimating the shelf-length of the ‘Settled Indian Accounts and Claims’ that date to the decade of deportation in the 1830s and belong to the Office of the Second Auditor in the Treasury Department. If stacked atop the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal, the accounts and claims would surpass the height of her torch. The entire series, covering the century between 1794 and 1894, would rise nearly twice as high as the Empire State Building. This mundane but monumental product of clerical labour is a tribute to the republic’s nation-building ambition, and reveals the immense pressure that it brought to bear on thousands of targeted Indigenous families.

One proponent of US deportation policy boasted that, at least in his small corner of the operation, ‘no business of similar magnitude, and complication, when all the circumstances are taken into view, was ever in so short a period systematised, partly settled, and brought into a form.’ The layers of bureaucracy gave cover to what was at bottom a matter of might-makes-right. John Ross, the incisive Cherokee leader, sharply observed that ‘justice and weakness cannot control the array of oppressive power’.

International financiers established joint-stock companies to invest in the lands of the dispossessed

None of this bureaucratic labour prevented the government’s scheme to deport 80,000 people from becoming an operational disaster. Supplies didn’t arrive on time, roads sank beneath floodwaters and became impassable, and rivers fell too low to support even shallow-draft steamboats. Winter storms lashed the migrants, spring rains flooded their camps, and cholera killed hundreds. Some federal officers were negligent. One agent stationed in the Choctaw Nation in present-day Mississippi was often too drunk to open his mail. Another, who ‘puffs and swells, and calls himself “the Government”’, exhausted his funds only a few days after setting out on the road with 800 deportees. Thereafter, the party lived on money borrowed from the victims themselves.

Though these crimes occurred far from the US population centre along the East Coast, the nation’s major cities were nonetheless deeply connected to them. The opportunities for profit attracted capital from New York, Boston and even overseas from London, creating a financial network linking dispossessed Indigenous Americans with middle-class investors on both sides of the Atlantic. International financiers established joint-stock companies to invest in the lands of the dispossessed. They underwrote state bonds to capitalise banks and finance the razing of indigenous farms. (I have written about this subject in detail elsewhere.) ‘Indian titles to extensive tracts of land’, boasted one bond prospectus, had recently been extinguished in Alabama; the potential profits were enormous.

William Wordsworth’s daughter Dorothy, who inherited a small portfolio of Mississippi bonds from her aunt, was among England’s middle-class bondholders who stood to profit from native dispossession. However, when the transatlantic economic panic hit in the late 1830s, the state refused to honour its debts. Mississippi and other states, Wordsworth charged, were ‘abandoned to utter profl[ig]acy’ and ‘doomed to suffer for their iniquity’ – referring not to their determination to replace Indigenous farmers with slave labour camps, but to their failure to meet their interest payments to creditors. With the exception of the Mississippi bonds, the poet insisted, his family was ‘in no way directly entangled’ with the ‘monetary derrangements in America’. Like other bondholders in the US and abroad, however, the Wordsworths were entangled not just in the financial mess but in the operation to deport native peoples.

From the cheery perspective of secretary of war James Barbour and many other Americans, the US undertaking to eliminate native peoples east of the Mississippi River was truly ‘modern’. In his view, it was founded in ‘justice and moderation’. ‘To spare the weak,’ he boasted, ‘is its brightest ornament.’ From the outset, the policy appealed to a small group of naive philanthropists, self-described realists who accepted as fact the oppressive conditions in which native peoples lived, and they therefore promoted deportation as a humanitarian solution. However, when native peoples didn’t agree to disappear, altruism gave way to a twisted logic.

Deportation, explained Lumpkin, the governor of Georgia, was the only way to rescue native peoples from ‘speedy extermination’. If they resisted, armed troops might have to expel them at gunpoint. If military action led to bloodshed, it would be the fault of those who chose not to move in the first place. In the summer of 1836, the US mobilised troops in Alabama and Georgia to arrest and deport defiant Creek families. State militia pursued the refugees through swamps and slaughtered them. The survivors, said one Tennessee militiaman, had to be ‘hunted up in the woods like wild beasts’ and killed in small gangs. One company from Alabama cornered a 90-year-old man in his cabin, shot him in the head, and stove in his skull with the butt of a musket. They raped several women and chased after a 15-year-old girl and shot her in the leg as she escaped into the bushes. ‘Under what authority?’ they were asked. ‘The people,’ they answered.

The ‘people’, organised as state militia, waded through mud and water in pursuit of the fugitives, ‘hunting up the Indians who yet infest the swamps’, as one volunteer put it, and scattering the survivors. ‘The savage,’ proclaimed one army officer, ‘should be no longer permitted to polute [sic] our soil with his foot.’ The country, said another, was ‘infected’. Week by week, militia tracked down the desperate refugees, killing 12 one day, 22 more two weeks later, then another 22. They followed trails of blood and corpses, seizing the possessions dropped by the survivors – quilts, cloth, powder and lead. Weak with hunger or simply too young, some Creek children couldn’t keep up with the pace of flight. Their mothers smothered them to death. On occasion, women suffocated their crying babies to prevent them from revealing their locations. Nearing capture, they sometimes killed their children and committed suicide.

In Florida, the US waged a seven-year war against Seminole families who, like the partisans of the Second World War, survived by hiding out in swamps and forests. The violence escalated, fuelled by disillusioned soldiers and desperate refugees. The secretary of war, reported a high-ranking officer, ‘goes for “extermination”’.

Why hasn’t the US expulsion of native peoples in the 1830s taken its place among the first modern deportations? Part of the answer lies in the very name ‘Indian’, which sets the victims apart from other people and situates the operation not within the modern history of mass deportations but in the context of what US administrators called ‘Indian policy’, overseen in the 19th century by a branch of the War Department called the ‘Office of Indian Affairs’, later renamed the ‘Bureau of Indian Affairs’. (In 1969, during the Indigenous occupation of Alcatraz Island, activists formed the ‘Bureau of Caucasian Affairs’ and promised to allot small reservations to white people ‘for as long as the sun shall rise and the rivers go down to the sea’.) Beginning with Christopher Columbus’s description of one-eyed men and people with dog snouts, Europeans used difference to rationalise enslavement and dispossession. They eventually developed a rich, self-vindicating legal tradition on the matter, much of it generated by scholars who had never before met a native person.

In 1823, John Marshall, chief justice of the US Supreme Court, invoked the difference ‘in character and habits’ between Europeans and Indigenous Americans to rule that native peoples had the ‘right of occupancy’ but not full title to their lands. Advocates of deportation relied heavily on the court case, since it enabled states to dispossess native peoples under cover of the law. They used the same justification to insist that treaties were not actually treaties. How could a contract ‘with a petty dependent tribe of half starved Indians be properly dignified with the name?’ asked Georgia’s senator John Forsyth. The insistence on essential difference exists to this day, though it is now just as often admired as scorned. It continues to obscure the similarities between the deportation of Native Americans and the expulsion of Turks, Greeks, Armenians and other victims of 19th- and 20th-century state-modernising projects.

It’s not just that many Americans fail to see the parallels. The emphasis on difference, whether valorised as savage or noble, exoticises the victims. Imagine if every book on Turkish policy towards Armenians began with a chapter on how radically different the victims were from the Turkish people. Or imagine a book on pogroms in eastern Europe that spent the first 50 pages describing the colourful rituals of Jews and exploring their unique worldview. The effect would be to concede part of the argument to the state: this population is fundamentally different.

The deep investment that many Americans have in US exceptionalism, in the belief that their nation has a providential mission to spread liberty around the world, prevents them from seeing US history clearly. From their perspective, the pivotal expulsion policy of the 1830s was either a good-faith effort to save Native Americans or, at worst, a mistaken but short-lived experiment. At the time, however, Americans understood exactly what was happening. They knew quite clearly that the US was sacrificing its republican ambitions for avarice. Just as the Russian and Ottoman empires were crushing Polish and Greek nationalist uprisings and deporting tens of thousands of people in the process, they said, the US was destroying the Indigenous nations of North America. ‘But let our countrymen shew some pity to a tribe exterminated within their own boundary, and not spend all their compassion on the unfortunate heroes of Europe,’ wrote a member of the Peace Society of Windham County in 1832, ‘for we have nearer home nations who have been more oppressed than Greeks or Poles.’ (Founded in Connecticut in 1826, this society was one of many religious organisations that condemned the US deportation policy.) To ‘the cruelty of Russian despotism’, charged The New York Observer, the US ‘adds the hypocrisy of a claim to republicanism’. One writer for The New-York Review compared the US with the ‘partitioners of Poland, the invaders of Spain, and the plunderers of India’. If the republic were to ‘dispose of thousands of human beings like cattle’, he asserted, the ‘wrongs’ would ‘go forth to the world’ and become a part of ‘national history’.

They asked if liberty and equality applied only to white Americans

A number of native people made the same point. James Folsom, a young Choctaw student, then attending Miami University of Ohio, insisted that the ‘American Republic’ would ‘go down to future eyes with scorn and reproach on her head’. Three Seneca leaders warned president Andrew Jackson that he was following the path of the Roman empire, which broke treaties, violated the rules of war, and ignored demands for justice, all in the interest of conquering the world. No people cut to the bone as incisively as the Chickasaw leaders who wrote to Jackson in November 1832. They asked the president to demonstrate

that the spirit of liberty and equality which distinguishes the United States from all the Empires, is not, as many in the world might imagine, a jealousy and defence of their own particular rights, an unwillingness to be oppressed themselves, but a high respect for the rights of others, an unwillingness that any man high or low should be wronged.

Would the US live up to its professed ideals, they asked, wondering if liberty and equality applied only to white Americans. The protestors, natives and newcomers, were right about the merits of the policy, even if they underestimated the commitment of future generations to whitewash US history.

Around the world, administrators of other states had no use for American exceptionalism. Engaged in their own modernising projects, they recognised that they could learn something from the US, with its seemingly boundless economic growth and rapid territorial expansion. In France, public intellectuals, debating how their nation could enact its own removal in newly colonised Algeria, discussed the US ‘incessantly’. In the 1830s, they began calling France’s new colonial subjects indigènes, a word once reserved for Native Americans, partly in the vain hope that Algerians would diminish as rapidly from disease as their American counterparts. As one French commissioner put it rather defensively in 1833, everyone admired how the US pushed out native peoples but, in North America, Indigenous residents quietly retired with their arrows and fish hooks as civilised man and his arts advanced; Algerians were better armed and less pacific.

Initially, some German intellectuals condemned the ‘inhuman system of butchery’ levelled against Native Americans. But by the early 20th century, they looked to the US as a model for how to deal with the Herero and Nama people in southwest Africa, whom German officials rounded up and nearly exterminated, an order of violence that Germany later imported into Europe. Notoriously, Adolf Hitler and other Nazi leaders envied the US answer to the ‘Indian Question’ and occasionally cited it when describing and justifying their imperial ambitions in eastern Europe. Nazi lawyers carefully studied US law that targeted black and Native Americans, admiring, as one did, Indians’ status as ‘a racial group placed under a special police power of the United States’. In the 1930s, the French, German and British governments all considered creating a Jewish colony in Madagascar, and Nazi officials nearly implemented the plan until military exigencies upended it in 1940. Presented to the world as a philanthropic enterprise, this half-baked scheme to create a semi-autonomous colony of Jews in a far-off land resembled the US plan to create an Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River a century earlier.

It would be facile to suggest that the deportation of Indigenous Americans in the 1830s led other nations to pursue similar polices with their subject populations. Few administrators possessed more than a cursory and misinformed understanding of US history, and in the 20th century, at least a few of them, including Hitler, gained their would-be expertise by reading the boys’ western adventure novels of Karl May. But the parallels are striking enough to conclude that the US belongs to the list of modern nations that practised a politics focused on populations – counting, evaluating, deporting and, sometimes, exterminating.

‘Indian Removal’ wasn’t just Indian policy; it was an organised state effort to remake the people within its borders for the purpose of digging more canals, laying more rails, mining more ore and cultivating more staple crops – a process that states soon began calling modernisation. If the US is exceptional in this instance, it has been solely in its ability to avoid the stigma associated with the mass deportations of the modern era.