There are many criteria by which to judge a society. Dostoyevsky recommended examining its prisons. Gandhi said to look at how it treats its weakest members. If you want to discover a society’s attitude towards authority, or to gauge the power of its official belief system, I suggest that you could do worse than look at its relationship with detective fiction.

Crime stories are one of the oldest literary genres, dating back at least as far as Cain and Abel. But the genre that concerns me here is the crime story’s modern descendant, in which a felony is committed in mysterious circumstances and then an individual follows clues and makes deductions to discover what happened. This is a relative innovation: the first modern detective novel is usually attributed either to William Godwin’s Caleb Williams (1794), or to Edgar Allan Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841). There is no doubt, however, that the 1860s saw the arrival of detective fiction as a whole. This was the decade that saw the publication of Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone (1868), ‘the first, the longest and the best modern English detective novel’, in the opinion of T S Eliot. In France, Émile Gaboriau published his first roman judiciaire in 1866; L’affaire Lerouge was a big success and spawned a series of novels starring the detective Monsieur Lecoq. Methodical and smooth — certainly in his later cases — Lecoq was an inspiration for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (although in A Study in Scarlet Sherlock Holmes dismisses him as a ‘bungler’).

Why should detective fiction have emerged at this time? There are some conspicuous material factors. Industrialisation and the growth of literacy meant that more people than ever before were able to read. To satisfy this new market, new machinery was developed that could produce cheap books in vast numbers. Booksellers in Britain set up stalls in stations. Their best-sellers were sensationalist, the kind of stories sneered at by literary types: ‘the tawdry novels which flare in the bookshelves of our railway stations,’ the poet and critic Matthew Arnold complained in 1880, ‘and which seem designed, as so much else that is produced for the use of our middle class, for people with a low standard of life’. Unabashed, ordinary readers were hungry for this kind of stuff; when the first detective novels came along, they lapped them up.

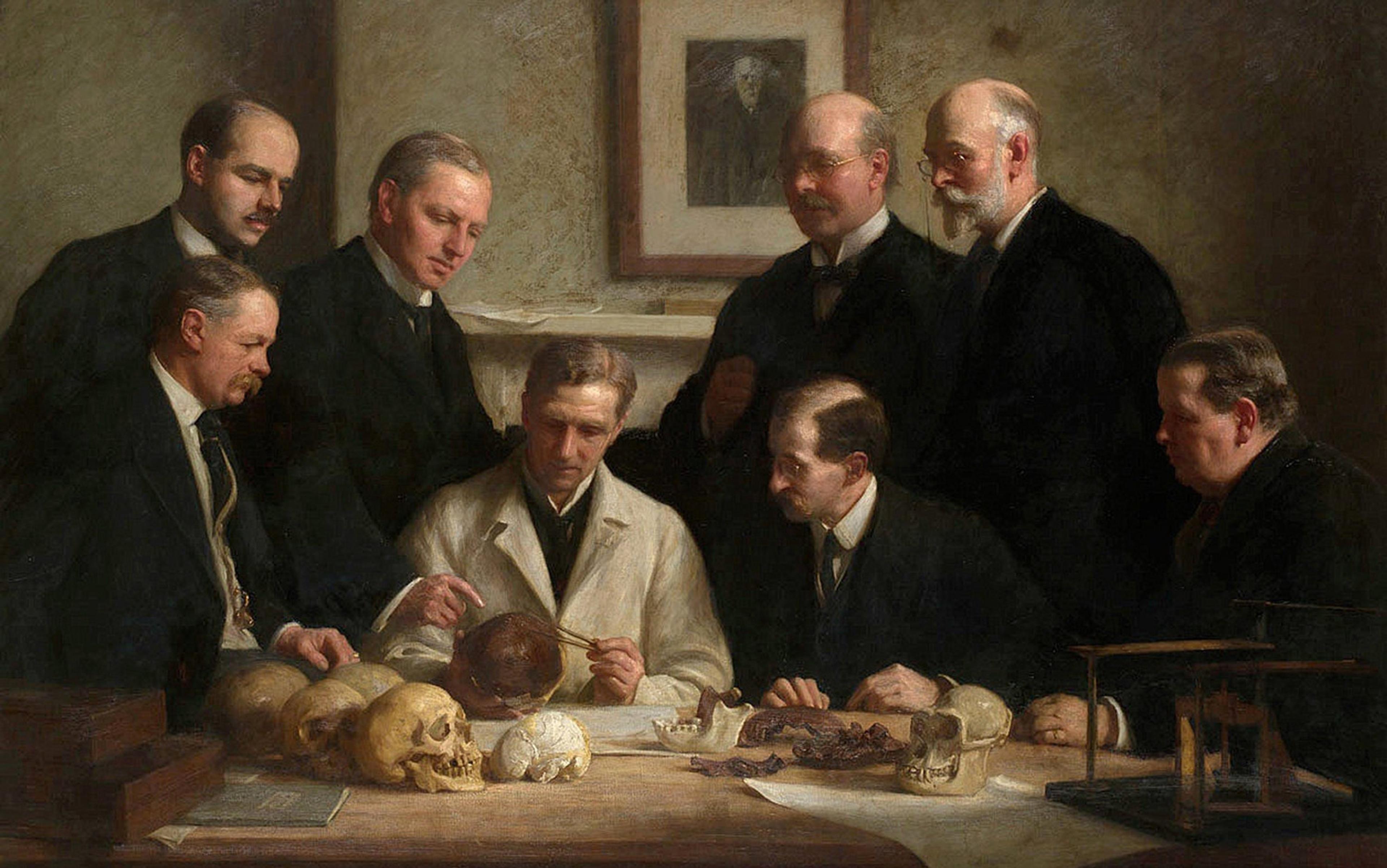

Of course, detective fiction could hardly have come about if not for the advent of the detective himself. The Metropolitan Police in London created its ‘Detective Branch’ in 1842, and the first of its policemen to come to wide public notice was Jack Whicher, who was called in to investigate a notorious child murder in Wiltshire in 1860 (the subject of the recent book The Suspicions of Mr Whicher by Kate Summerscale). Newspapers followed the Road Hill House case avidly, describing every twist and development, until there was barely a person in the country who did not have a theory about who had killed the three-year-old Francis Kent.

All of these elements were undoubtedly important. But why did detective stories become such huge best-sellers almost overnight? What accounted for the sudden fascination with the figure of the detective? The unlucky Francis Kent’s father happened to be a government factory inspector, another profession that emerged at around this time, and yet factory inspectors didn’t suddenly become heroes of the popular imagination.

The solution can be found if we ask ourselves what a detective actually does. If nothing else, he (and, later, she) is a problem-solver; someone who can restore order where there is chaos. Faced with the worst crime (what could be more existentially troubling than a murder?), the detective gives us answers to the most pressing and urgent questions: not only whodunit, but how and why and what it means. He does all this by taking us on a journey, discovering pieces of evidence, seeking out hints and clues. In the best examples of this game, we see everything that the detective sees, yet we are unable to solve the crime ourselves. Only the detective, in a final display of mastery, can reach the correct conclusion. We need him, with his special knowledge and abilities, to make sense of it all.

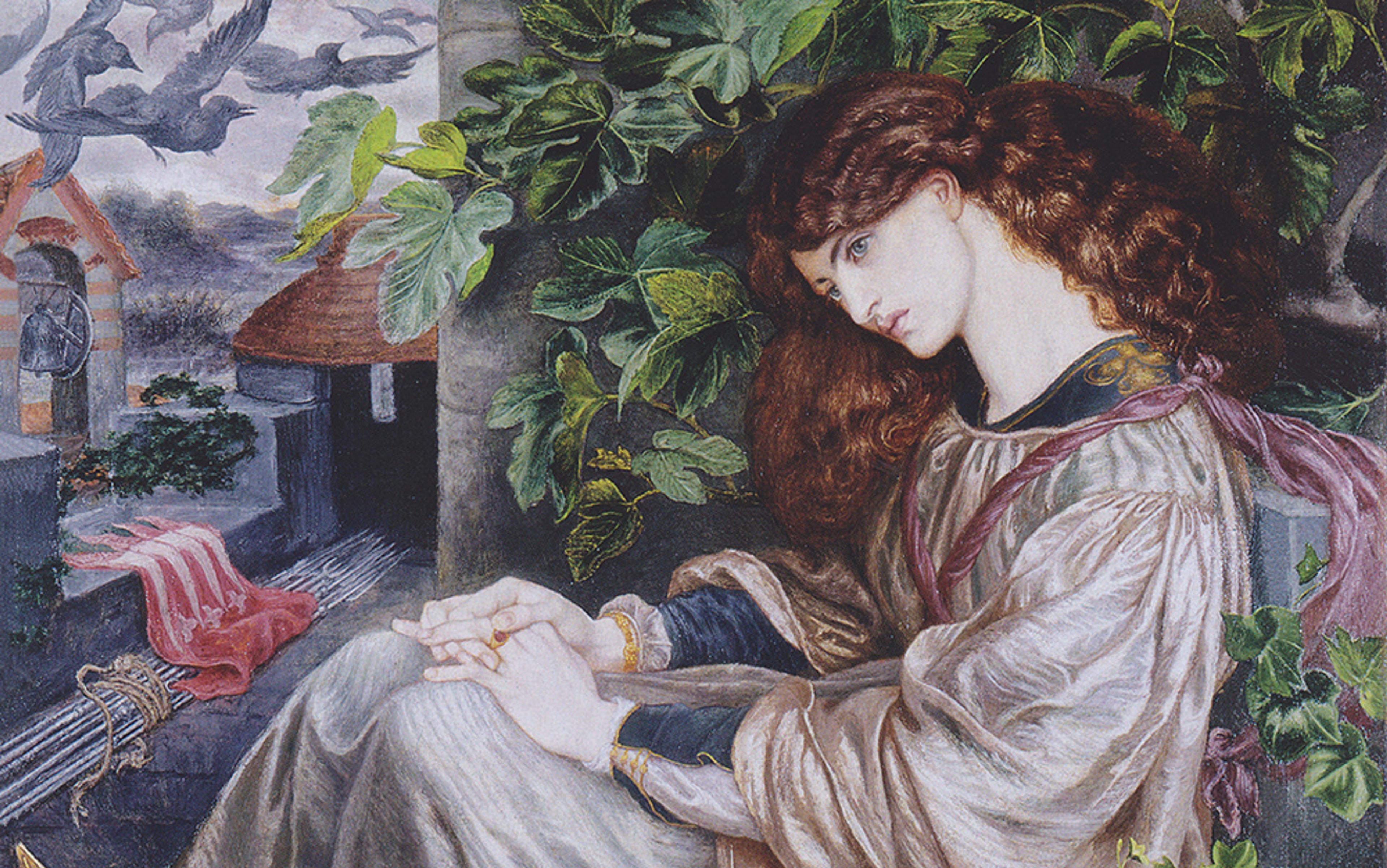

In other words, a detective is a kind of priest. Throughout history, priestly castes have boasted a unique capacity to answer the great riddles of existence, and it is surely more than a coincidence that, during the detective fiction boom of the 1860s, intellectual developments in Britain were profoundly undermining the Church’s traditional monopoly on such matters. In 1859, after two decades of delay, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species. The theory of evolution did not emerge from nowhere; even before Darwin’s ideas went public, many were already moving away from the literal interpretation of the Bible stories. But no single event played such an important part in the shift from a religious to a secular society, and no other book did so much to shake the authority of clerics and their official answers. This left a cultural vacuum, and in a changing world full of new dangers and problems, the fictional detective stepped into the breach.

One only needs to look at the names of famous sleuths to see how deeply they draw on the authority of religion. The most obvious example is John Rhode’s forensic scientist Dr Priestley in the 1920s, followed in the 1950s by John Creasey’s Commander George Gideon (think hotel Bibles). Even among contemporary characters, names with religious connotations are common: Adrian Monk and John Luther have both been recent hits on television, while Michael Dibdin’s Aurelio Zen, James Patterson’s Alex Cross and Leslie Charteris’s Simon Templar, alias ‘The Saint’, are hugely popular literary creations.

It isn’t only the names that give the game away. Consider Holmes, the greatest fictional detective of them all. He is (probably) celibate. He acts in the ordinary world, but his natural habitat is a mystical retreat in which he isolates himself for weeks, emerging with insights that can resolve the perplexities of those around him. His London address at 221B Baker Street is a kind of monastery in the heart of the metropolis. ‘For days on end,’ Dr Watson reports, ‘he would lie upon the sofa in the sitting-room, hardly uttering a word or moving a muscle from morning to night.’ Holmes is like a Franciscan, periodically leaving the friary to offer wisdom to the wider community. Or perhaps he is a shaman, locked in his refuge, taking powerful drugs and communing with spirits before returning to ordinary life with mysterious powers and solutions.

The first Holmes short story ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’ (1891) clearly exhibits the great detective’s other-worldly nature. Living alone after Dr Watson’s marriage, Holmes has stayed in his rooms for weeks, ‘buried among his old books’ and taking cocaine. Upon the arrival of a certain Count Von Kramm, Holmes quickly demonstrates his superior powers of perception, revealing the count’s true identity as the King of Bohemia. Later, the detective disguises himself — as a clergyman — in order to discover the secrets of the opera singer Irene Adler, who is suspected of blackmailing the king. Holmes contrives the threat of a symbolically resonant inferno, and Adler promptly reveals where she is hiding a compromising photo of the monarch, thus solving the mystery. In a final twist, Adler tricks Holmes and vanishes with the photo. Watson declares that for Holmes she was always ‘the woman’, the only one he ever really admired, but of course he has no physical relationship with her. With his supernatural powers and tantalisingly glimpsed human flaws, Holmes is a disguised and idealised vision of priesthood, fit for an age that was painfully losing its faith in priests. No wonder he was popular.

One of Holmes’s best-loved rivals goes a step further. G K Chesterton’s Father Brown is actually a priest — a quiet bumbler with an unfailing intuition for mysterious crimes. Like Holmes, he often disarms his prey by disguising his true character. In the first Father Brown short story ‘The Blue Cross’ (1910), both the master thief, Flambeau, and Valentin, the Parisian detective chasing him across England, are completely taken in by the little priest’s naive, ‘mooncalf’ demeanour. Although Chesteron was not a Catholic when he started writing the stories, he converted in 1922, midway through the series, and Father Brown is based on Father John O’Connor, the priest who influenced his conversion. Chesterton’s intention was to construct ‘a comedy in which a priest should appear to know nothing and in fact know more about crime than the criminals’, using his understanding of human nature. By creating an investigating cleric, Chesterton might have been trying to close the gap, to put the genie of secularisation back into the bottle and restore the prestige of the priesthood. But it wasn’t to be. The fictional detective is not simply a replacement for a deposed caste of clerics. He represents a challenge to any system that claims to offer all the answers.

When organised religion lost its monopoly on belief, many countries turned to other forms of ideology, creating political or politicised ‘priests’. In almost all of these cases, detective fiction enjoyed a brief burst of popularity before being snuffed out or bullied into toeing the line of the new, post-religious regime. In 19th-century Russia, Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Anton Chekhov had written crime fiction, but proper detective stories did not take off until after the 1917 revolution and the fall of the Tsar. The ‘Pinkerton Phenomenon’ of the 1920s, named after the real-life crime-fighter Allan Pinkerton, scourge of Jesse James, inspired a wave of pulp novels, usually featuring swashbuckling, American-style heroes fighting international crime. These sold in their millions, but the Soviet government was never comfortable with the genre: Stalin banned it, and the restrictions remained in effect until after his death in 1953. Italy followed a similar pattern. In 1929, the book publisher Mondadori started bringing out I libri gialli — cheap detective novels with yellow covers, which sold in huge numbers. However, just like with the Soviet regime, the Fascist state disapproved and banned the genre entirely in 1943.

True-crime stories were very popular in 19th-century Germany, and a few writers dabbled in crime fiction. However, detective fiction did not begin in earnest until after the end of the First World War and the fall of the Kaiser. One of the most influential of the new authors was Erich Kästner, author of Emil and the Detectives (1929). When they came to power in 1933, the Nazis burned Kästner’s books, but they did not ban the detective genre outright. Instead, they controlled it, outlawing foreign detective writers and ensuring that German Krimis — which were hugely popular — depicted honest and highly competent policemen upholding the rule of law. The genre became, in effect, a part of the Nazi propaganda machine.

Bucking the pattern slightly, there was no early flourishing of detective fiction in Spain. Then again, despite a brief period of liberalisation during the Second Republic of the 1930s, the Church did not surrender its hold on power until the dying days of General Franco’s Catholic regime. The genre really came to life with Manuel Vázquez Montalbán and his Pepe Carvalho novels, the first of which came out in 1972, when the dictatorship was on the point of collapse and Spaniards were looking towards a new, democratic future. Written in an almost surreal style, with a food-loving ex‑Marxist hero who had also worked in the past for the CIA, the novels captured much of the energy and experimentalism of post-Franco Spain.

The hard-boiled writers simply took the cowboy from the wild frontier of mountains and prairies and transplanted him to a new hostile locale: the mean streets

And what about those countries that didn’t replace the Church with an all-encompassing political ideology? Here the American experience is particularly interesting. Pulp detective stories like those that appeared in Black Mask magazine were hugely popular in the US following the First World War. Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon (1930) was the first truly distinctive American detective novel. Three years later, Prohibition — the most blatant imposition of religious authority in US history — came to an end, and by 1939 the genre had come of age with Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep, in which the detective Philip Marlowe made his debut.

The rise of this American ‘hard-boiled’ style marked a fundamental shift. Tired of the purely intellectual puzzling of the British writers of the Golden Age of detective fiction, with their murders resembling stage conjuring tricks, Chandler and Hammett wanted to produce something authentically gritty. Their stories were influenced by the cowboy, a home-grown US archetype whose civic-minded decency and austere self-reliance both call to mind the figure of the sleuth. But the cowboy inhabited an unforgiving, anarchic world, far from the cosy drawing rooms of Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot. If you leave aside the mystery elements of their plots, it would not be much of an exaggeration to say that the hard-boiled writers simply took the cowboy from the wild frontier of mountains and prairies and transplanted him to a new hostile locale: the mean streets of the cities. In such an environment, only a very imperfect heroism is possible.

In The Big Sleep, Chandler’s Marlowe is quite ineffective at preventing further bloodshed: several people are murdered before we reach the mystery’s resolution. Worse, the killer of Rusty Regan, whose disappearance the detective was called in to solve in the first place, is eventually revealed to be the daughter of Marlowe’s own client. In a murky world of blackmail and homosexuality — then a scandalous subject — there are no clear good guys and bad guys. The hero ends up killing people, while the murderer turns out to be insane and is sent to an asylum.

This was radical. The essential structure of previous detective novels persists — a crime is committed and, by the end of the book, it is resolved. But unlike Holmes or Poirot, the US detective is not a ‘master’. He is not superhuman or pure. He doesn’t belong to an elect, with knowledge beyond the grasp of ordinary people. He is one of us, as ordinary and fallible as the reader. And so the detective no longer furnishes his solutions from a position of superiority. He struggles to overcome crises — to solve mysteries — just like anyone else. He muddles through until, in the end, he finds some kind of answer, though it is rarely the neat resolution of an Agatha Christie novel. Loose ends are left trailing; the crime might have been solved, but the world remains as messy and difficult as it was before.

Perhaps such a leap could only have taken place in the US, with its separation of church and state. The result, however, was to revive a genre that was in danger of becoming a footnote of literary history. Now that he was everyman, the detective became a mirror into which any society could gaze. Perhaps a traditional police detective such as Colin Dexter’s Inspector Morse, attuned to hidden messages and ethereal harmonies, might confine his investigations to the quasi-monastic world of Oxford, but more recent detectives give clues as to the underlying preoccupations or our time. Just look at their names: Jo Nesbø’s Harry Hole, Mark Billingham’s Tom Thorne and Arnaldur Indriðason’s Detective Erlendur (from the Icelandic for ‘outsider’) all point to a sense of isolation and emptiness, a world where, perhaps, no meaning or meanings can ever be found. At the same time, the common targets of the contemporary detective’s investigations — corrupt politicians, or the failures of entire institutions, as in the US TV series The Wire — show clearly where the threats to our society are to be found.

In the beginning, the very existence of a fictional detective was a challenge to state ideology. Today’s detectives continue to fight for a better world, struggling to expose the forces that constrain and destroy us. The genre remains astonishingly popular; according to the Bowker Books and Consumer survey, in 2012 readers in the UK bought 35 million crime novels, which constitutes a third of all fiction titles. Here’s evidence that, in the West at least, despite threats to our liberties, we are not yet living in an authoritarian regime. But it also shows how little we now trust any totalising world-view to resolve our existential crises. We have gone beyond believing in belief. The modern detective — cynical, world-weary but stubborn and compulsively probing — reflects our own attempts to find answers about existence. Not through the mouthpieces of social order, but by ourselves, as individuals, each in his or her own way. Day by day. Murder by murder.