Across at least five decades, from Susan Brownmiller to Gail Dines, some feminists have denounced pornography for enacting and inciting violence against women, making its viewers into psychologically inert consumers or, worse, sexual aggressors. Andrea Dworkin put forth this view in Pornography: Men Possessing Women (1981), where she defined the genre as ‘the blueprint of male supremacy … the fundamentalism of male dominance … the essential sexuality of male power’. On such grounds, Dworkin, together with Catharine MacKinnon, objected to pornography’s constitutional protection as free speech, and proposed legislation to ban it, alleging it did not say or represent the degradation of women, but concretised and performed it, made it real.

Dworkin’s contributions to feminist thinking about pornography are radical and profound. She insisted that we examine and take seriously what pornography shows us: its documenting of the sexual use of women’s bodies, as well as men’s consolidation of their ‘social power’. Displaying genital action, hardcore pornography – especially the visual kind that became popular during feminism’s second wave – shows to an unusual degree the ways that sexed bodies collide. Social dynamics like misogyny, heteronormativity, xenophobia and racism shape these collisions. With such conditions informing pornography and its consumers, sex becomes a stage for the mingling of persons. Often – but, crucially, not always and not uniformly – this interplay entails hierarchy: demands are issued, often by men; actions are coerced, often by men; body parts are pushed or positioned or operationalised, often by men. The recognition of these patterns led many feminists to deduce that pornography promotes – that it desires and celebrates – the denigration of women.

Having spent years in library archives reading obscene works, I’ve found that pornography says many things at once. It can make us think. It can urge people to consider sex from multiple perspectives and think about how it shapes our regard for other people. The actions captured in pornography convey more than they seem to – as all cultural works do. Dworkin’s indictment is so sweeping that she claims pornography, from Greek antiquity to her present, levelled all women to the same status, making them into the ‘lowest class of whore’, the ‘brothel slut available to all male citizens’. There is much to challenge in this thinking, not least its denigration of sex work, but also its lack of precision, its unsubstantiated view that all pornography celebrates the extreme subjugation of women. My objection is to Dworkin’s recommendation that we dispense with considering what an individual work of pornography says about the actions happening within it. It is tendentious to collapse millennia of sexual representation into a single function, an overgeneralisation that prevents us from approaching millions of works of pornography with a curious, even critical eye.

Those of us who want to think in a more sophisticated way about pornography won’t get there simply by adopting a pro-pornography position, an argument that, say, sex is inherently good, that everyone has a right to it, that we should rid sex of shame. Such a position advances its own kind of dogma, imposing the view that sexual pleasure is essential to full human potential, and thus potentially alienates those who – for any variety of religious, cultural, gendered or physical reasons – have a more reserved or alienated relationship to sexual activity. Moreover, pornography proliferates tenaciously and resiliently across media forms and doesn’t suffer existential crises. It doesn’t worry about people who don’t like it.

A more open and ecumenical approach, invested in neither condemning nor defending pornography, encourages us to tolerate looking at pornography without knowing in advance what we’ll find. Literary critics like me recognise this as close reading: a methodical examination of pornography’s contents. All of its contents, and not just the juicy bits. Encountering examples from the pornography of the past can also attune us to what is actually happening in pornographic works, then and now. What we find in historical examples of pornography sometimes resembles what Dworkin thinks is in all pornography: sometimes brothel workers are the main characters, and sometimes they do suffer coercion and debasement by men. But sometimes sex workers decline sex, sometimes they seek it out and enjoy it; sometimes young women object to toxic masculinity even as they applaud a penis for creating erotic sensation. Sometimes cross-dressed, heterosexually identified men find themselves desiring a penis more than a vagina.

If we refuse to recognise the vast diversity within pornography, we miss its complex accounts of sex and desire as different people in various social positions experience it. When we refuse to apprehend the full contents of pornography, we inadvertently overlook that it is frequently aware of how regimes of gender, misogyny and heteronormativity shape sexual contact. Dworkin and other anti-pornography feminists are right that pornography contains violence. But they are wrong that pornography contains only violence, that pornographic violence is inherently harmful, and that the genre does only one thing to women, over and over, and therefore deprives them of humanity and dignity. To imagine history as an undifferentiated state of violent sexism, and to imagine pornography as its primary form of propaganda, deactivates the capacity to see it for its breadth and scope across history, for its content beyond dominant, masculinist narratives.

Experimental fiction of 18th-century Britain braided pornographic description with feminist principles

I’ve spent more than a decade reading pornography from the 18th and 19th centuries. Far from silencing women and eroticising their subjugation, pornography sometimes minutely considers the personhood of sexual participants, often giving voice to women who know – expertly – that penetrative sex will transform their identity, and that they have little power over what comes of their bodies under patriarchal culture. At key intervals, pornography envisions alternative realities in which sex might be had under conditions of equity and freedom, even as it provokes erotic feelings. Pornographers fuse these ideas into sentences and paragraphs of genital description. Or they use footnotes and digressions to make sex share the page with social criticism, especially as spoken by women or gender-bending men. Granted, radical ideas are quickly sidelined when, after a moment of deliberation, a pornographic plot resumes its sexual path. Readers might therefore ignore, override or forget the social criticism. But pornographers did not allow readers to see sex without also seeing the social hierarchies occupied by sexual actors.

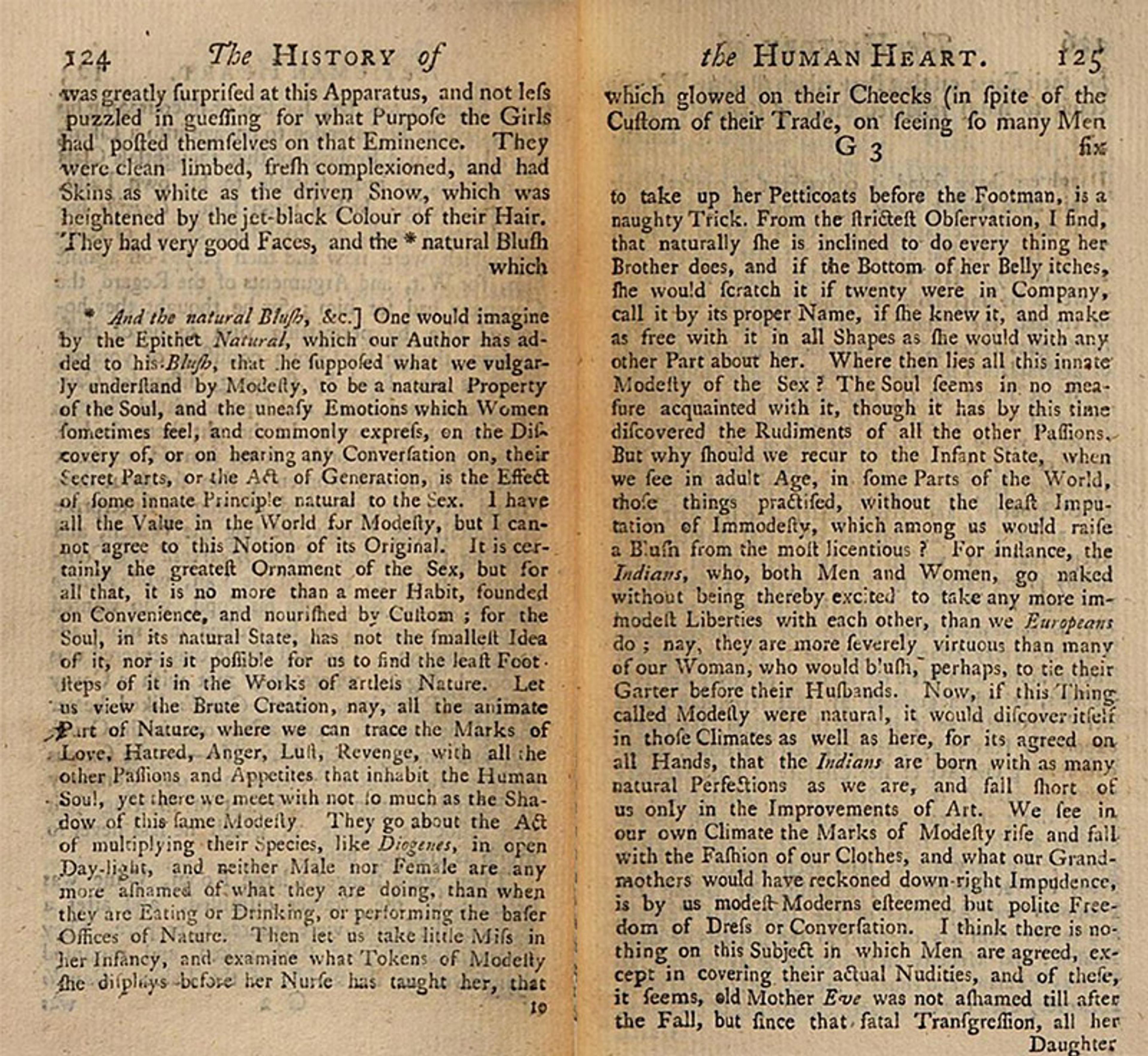

Sex, pornography tells us, is an encounter that is shaped and informed by its social world. The entropic, experimental fiction of 18th-century Britain braided pornographic description with explicitly feminist principles. Consider this passage, which examines how moral customs make disproportionate demands of women. This meditation on femininity comes from the little-known novel The History of the Human Heart; or, the Adventures of a Young Gentleman (1749), which follows the sexual pursuits of a young man through his rural adolescence, his London coming of age, and his European grand tour. The anonymous writer disputes the dominant cultural belief that women are innately modest. He calls modesty ‘the greatest Ornament’ of women, but he doesn’t believe it is a natural condition. Rather, it is a learned behaviour reinforced by a sexually conservative culture, ‘a meer Habit, founded on Convenience, and nourished by Custom’, mistaken for a natural attribute because it is so common among women in a culture that requires their virginity for respectable marriage. The pornographer, a keen observer of human behaviour, knows that modesty is socialised rather than inborn because every little girl ‘is inclined to do every thing her Brother does, and if the Bottom of her Belly itches, she would scratch it if twenty were in Company.’ Far from being naturally modest, girls will masturbate before company – ‘bottom of the belly’ is the top of the vulva – and would call her clitoris ‘by its proper Name, if she knew it’. Left to their own devices, girls and women will have an exhibitionist, plain-spoken relationship to their own bodies.

Footnote from The History of the Human Heart; or the Adventures of a Young Gentleman (1749), printed for J Freeman, London. Courtesy Google Books

This passage is a fraction of a long footnote in the Human Heart. It challenges the notion that women naturally possess a trait that inclines them to blush at the mention of sex, and it runs across several pages that, simultaneously, describe an erotic dance by women sex workers. The pornographer expects the reader to indulge genital display and erotic arousal concurrently. As they receive details about women’s masturbation on the top of the page, they read below that modesty imposes on women’s natural openness and candour about their bodies. The concept was invented, the note speculates, by moral philosophers who, ‘foreseeing these Inconveniences, feigned a supposititious Virtue, which they called Modesty, and recommended it to the Fair Sex.’ The effect of this psychological shaping is to restrain women from independence and ambition, ‘keep[ing them] within Limits they would be naturally prone enough to leap over, if not guarded by this imaginary Fence.’ Such a discussion should surprise anyone presuming that pornography is interested only in the lurid presentation of sexualised bodies.

The footnote claims modesty is a good thing that preserves sexual order but disputes it is innate to women. Questioning the naturalness of human characteristics, this pornographic work joins philosophical debates of its time. In the late 17th century, John Locke disputed the innateness of ideas and character, prompting decades of debate about the degree to which we possess certain forms of knowledge at birth. The Human Heart author adopts a Lockean position on women’s chastity – that it is not inborn – but also squares with moral philosophers who, nonetheless, promoted sexual continence for contributing to social order and stability. Women were the targets of this enforced chastity, an inequity fortified by 18th-century natural philosophy (what we now call science). Medical discourse fostered the belief that women and men are fundamentally different at the level of anatomy and of psychology. Indeed, the modern gender binary ossified in this period. But here, in a pornographic novel, we find an assertion that liberty and autonomy are craved by all people, all genders. The passage discusses women not to eroticise or subjugate, but to animate and enfranchise, and to do so on a philosophical basis. What would Dworkin say to this, convinced as she is that pornography from any and every moment in history diminishes women, violates them, reduces them to their sexual function?

When genitals were laid bare by pornographic narrative in the 18th century, they did not only or always serve men’s pleasure. As works tantalised with genital detail, they tended to talk also about the social aspects of sex, making readers think about how sexual freedom is curbed for some people but not others. Such analysis is easily overlooked when we’re inured to the notion that pornography not only documents but produces misogyny. Theories about pornography’s injustice are alive and well in anti-pornography writing. A recent book by Bernadette Barton, which mourns that ‘raunch culture’ unconsciously suffuses the sex lives of young people in our own time, echoes Dworkin’s argument that all pornography renders women as sex workers, and that to be rendered a sex worker is a debasement. However, 18th-century pornography often featured sex workers as psychologically complex human actors not reducible to a genital function – indeed, the erotic dancers in the Human Heart end up declining penetrative sex work. Anglo pornography of the 18th century was sometimes equally committed to challenging a sexist culture as to titillating readers with lewd images. It experimented with the kinds of things we can know or surmise from sexual contact.

Pornographers found penetrative sex especially relevant for critical speculation because vaginal sex was a tool for organising society in this time. It consummated marriages, made single women unmarriageable, led to pregnancy, and otherwise caused permanent changes in women’s social identity. Men, of course, enjoyed large degrees of sexual licence, both within and without marriage. The weight attached to chastity was a topic of great cultural concern for young women and the male relatives responsible for overseeing their marriages. Pornography, candidly examining the conditions under which penetrative sex happens, regularly showed women objecting to sex, claiming the importance of their virginity, and expressing aversion to the men pursuing them – often to no avail, being forced to have sex anyway. These works are forthright about a central cultural hypocrisy: that in a culture that fetishised their chastity, women were largely ignored when they said no to sex, as when the hero in the Human Heart ‘stifled’ and ‘overwhelmed’ a resistant virgin before raping her. The 18th-century reader was not simply asked to find this dynamic arousing, but was educated about its inequity. Contrary to perpetuating patriarchal dominance, these works show the fraudulence of gender hierarchies that trace men’s primacy to their sexual power.

Long before Jacques Lacan and Judith Butler, this pornographer saw the phallus as illusory

Dildos sometimes lead to feminist discovery in 18th-century pornography. In one work, The Progress of Nature: Exemplified in the Life and Surprizing Adventures of Roger Lovejoy (1744), adolescent girls find a dildo in an aunt’s bedchamber and spend pages deliberating its purpose. Drawing on a centuries-old European tradition of prostitute dialogues, in which an experienced bawd trains an initiate in the arts of sexual commerce, the more experienced Miss Forward explains genitals and sex toys to her innocent friend Polly. They acknowledge the penis as a source of power and ambition, and observe that the dildo – strong, erect and durable – in some ways resembles it. The penis ‘is that arbitrary he that enters his Dominions, and ravages far and wide … in the Gratification of his Pleasures. He plunges Headlong into all the Recesses, demanding every thing, denied of nothing, enjoying and bestowing every Rapture.’ Patriarchal right, so far, originates in men’s sexual power.

But the women soon qualify the potency of the penis. Miss Forward finds it to be, in crucial ways, unlike the dildo: whereas the dildo remains constantly erect, the penis ‘contracts himself like a Snail’, becomes ‘mean and pitiful, sneaking and supple’ in the absence of feminine beauty. Men, the young women realise, do not in their essence possess strength and power. Rather, they require an object of desire to beckon them to action. Men’s claim to uncontested social dominance, therefore, is premised on a faulty anatomical analogy. Long before Jacques Lacan and Judith Butler, this pornographer saw the phallus as illusory, an attribute that becomes associated with masculinity through a series of unstable connections. The penis, the girls agree, is ‘only something he has about him, that may be equivalent to, tho’ different from what we have about us.’ These girls obviously recognise their own genitals as valuable and advantageous. And other scenes describe the vaginal and clitoral pleasures of masturbation and penetration. Anatomical sexual difference is accepted, even celebrated, but gender hierarchy is not – equivalence is the relationship posited between men and women.

The dildo’s perpetual erectness made waves throughout pornographic writing. It raised existential questions for men. In A Spy on Mother Midnight (1748), a cross-dressed male narrator convinces a woman of his penis’s superiority so fully that she incinerates her dildo. Truly a fantasy, since ivory – like glass, a common material for dildos – would be unlikely to burn in a bedchamber fireplace. In the hubris that leads this narrator to boast of his penis’s triumph over this ‘inanimate Rival’, the narrator contemplates becoming a dildo. He finds himself wishing ‘that it might be the Fate of my Spirit to inform, in its next Transmigration, the Body of one of these Implements. What a delicious Thought … how many Cuckolds should I make in that Figure, more than I’m able to do in my own Proper Person!’

A dildo – always erect, never flagging – can penetrate more often, seduce more women, humiliate more husbands. Women also might show greater sexual enthusiasm to a dildo, a state of joy they are usually shamed from sharing with men: ‘Oh! to be hugg’d, handled, fondled, caress’d, and put ------- with their own fair Hands, and to find them yield to the Dictates of glowing Blood and stimulating Nature, without that Reserve and Coyness they sometimes assume … when a Man’s in the Case!’ The dashes playfully redact a key detail – that women ‘put [dildos into their vaginas] with their own fair Hands’, and it is exactly this extreme, disinhibited intimacy the man craves. The very object of sexual desire shifts: he wants not to dominate a woman through penetrative sex, but to become an object directed by a woman into her own body – an object, ultimately, that disappears.

British pornographers experimented with philosophy piecemeal, floating potentially transformative ideas, then retreating. By contrast, 18th-century French pornography, written in the decades leading to the Revolution, produced politically disciplined theories of personal liberty. While French pornography’s libertines promoted the unabashed fulfilment desire in enclosures like convents and chateaus, British pornography experimented with sex as it befell unremarkable characters (often inexperienced adolescents) in quotidian environments – gardens, parks, brothels, bedchambers, drawing rooms, taverns. In these proximate contexts, sex acts took on significance as everyday encounters available for consideration by an increasingly wide swath of readers, as print and literacy became more accessible. And as readers developed tighter affiliations with books, pornographers pulled together, in a slapdash manner, various threads of philosophy that could be tested against sexual experience, reimagining pornography’s lessons.

Stories of heterosex, seduction, rape, erotic performance and masturbation served as thought experiments about how people experience sex, but also how they experience the world. Pornography always understood that perception and aesthetics do not occur in a vacuum. Sexual encounters between persons provoke questions like: where does desire originate, and what is its object? What do genitals look like, and should we see them? Is seeing them at all like feeling them? Is modesty a social good, and at whose expense does it operate? Can sex be refused? Does sex cause harm? Pornographic narrative in the 18th century brought sex to bear on philosophical postulations, asking if there are epistemological limits, even risks, to the kinds of generalisations philosophers made. Social orthodoxies about two sexes are discovered to be not descriptions of simple reality but a superficial overlay on top of wildly different social practices. Pornography shows us that women are as inclined to ambition and freedom as are men. It shows us that men’s power is, like their erections, temporary, contingent, and it shows us contestable men who want to be objectified and sexually passive. Pornographers knew that life in an outwardly rigid heterosexual and patriarchal society was complicated and unjust. They resisted norms that intellectuals and revolutionaries would later attack.

Pornography foregrounds the potential incoherence of theories of civil society

Philosophers, especially empiricists, aesthetic theorists and moral philosophers worked toward a universal model of how individuals acquire knowledge, taste and virtue. Amid the clashes of modernity, philosophers wanted to understand minds operating in predictable ways. Eighteenth-century pornography runs against the grain of contemporary philosophers, often describing its characters, especially men, in states of perceptual distortion. Men’s lustful ‘Imagination’ can cause them to see firmness in a breast that is in fact ‘flabby as a Piece of Tripe’ (The Progress of Nature), or to feel ‘Extasy and unspeakable Rapture’ with a repugnant partner by holding the ‘Idea’ of their beloved foremost in their minds (the Human Heart). British empiricist philosophy tried hard to rationalise the components of human knowledge, merging individuals’ ‘ideas’ and ‘imagination’ with an observable, objective world. But sex, pornography asserts, disrupts this communal sense, leading us to see what is not there or to fantasise erotic ideals. Conceding individuals’ particularised perceptions, pornography foregrounds the potential incoherence of theories of civil society, asking how social cohesion can happen if individuals perceive their reality differently, a conundrum Enlightenment-era philosophy itself often failed to admit. How are we to believe men relished their autonomy when, as pornography showed us, they also wished to be absorbed into women’s genitals?

Pornography shamelessly foregrounds private experience, and it says we can learn things from sex we can’t learn any other way. Or, learn not from sex itself, but from reading about it, seeing people have it, and recognising the social contexts that surround it. If we acknowledge that pornography says many things at once – like, that the same sex act can gratify one person and violate another, or that gratification and debasement can be the same thing, or that heterosexuality can feel good but also oppress – we can allow it to activate our knowledge about the world and about other people. It can teach us that there is no one way to see an objective reality, that other people possess their own perspectives, and that our minuscule desires might set us at odds with a larger common good.

All of this is to say that pornography is remarkably honest, and not simply because, as anti-pornography feminists allege, it documents patriarchy’s debasement of women. Rather, it is honest because it showcases the hard, often confusing work of reconciling private desire with public life, of admitting that sex with others can be unethical, of distinguishing between fantasy and reality. Antique pornography makes these contradictions obvious, circulating knowledge that we think, today, is at odds with eroticism. But perhaps it isn’t – perhaps there’s a utility to pornography’s mixed messages. Perhaps it was designed to confuse us, the better to underscore the clarity with which we should enter into the messy endeavour of sex with other people.