Contemporary events appear in ever-shifting configurations. They seem to be entirely contingent, their amplification on the global scale dependent on how many people are paying attention. The vicissitudes of spotlighting various events are daily, if not hourly: something that was the focus of attention yesterday may be forgotten today. A massacre and a wardrobe malfunction are put on the same level of intense scrutiny and curiosity, attitudes that just as quickly latch on to another object. As a result, vital issues flash by before our eyes, only to be displaced and buried under piles of trifling matters.

In my book Dump Philosophy (2020), I treat these phenomena of the Information Age as part of a global ‘dump’, where all qualitative differences are erased and where the nihilistic attitude of generalised indifference rules the day, despite peaks of usually superficial engagement. It is with a view to resisting the bulldozing forces of the global dump that we need patient reflection and careful philosophical analysis, lingering with a singular event, being or image. Plato’s question throughout the Republic was: what could be saved from oblivion? Which tale, conveying crucial ideas such as justice, beauty or the good, would be transmitted further to others and into the future? These questions are ours, too.

The story I want to save here is that of the trenches dug up by Russian troops in Chernobyl’s exclusion zone, early on in their brutal assault on Ukraine. Trenches in Chernobyl may appear as one of those peculiar shards that kaleidoscopically and only momentarily make up the category of ‘current events’. Still, it is imperative to think through the absurdity, the staying power, and the subterranean connections linking this ostensibly fleeting military disaster to the catastrophe that took place in Chernobyl 36 years prior. Despite the relatively quick withdrawal of the occupying forces from this place, this story (which is more than a ‘news story’) is far from irrelevant. If we look a little closer, we can espy in it a strange condensation of everything that went wrong, and continues to go wrong, at the site of the nuclear accident. And that site, in its turn, condenses the modes of thinking and acting that continue to steer the world toward global disaster.

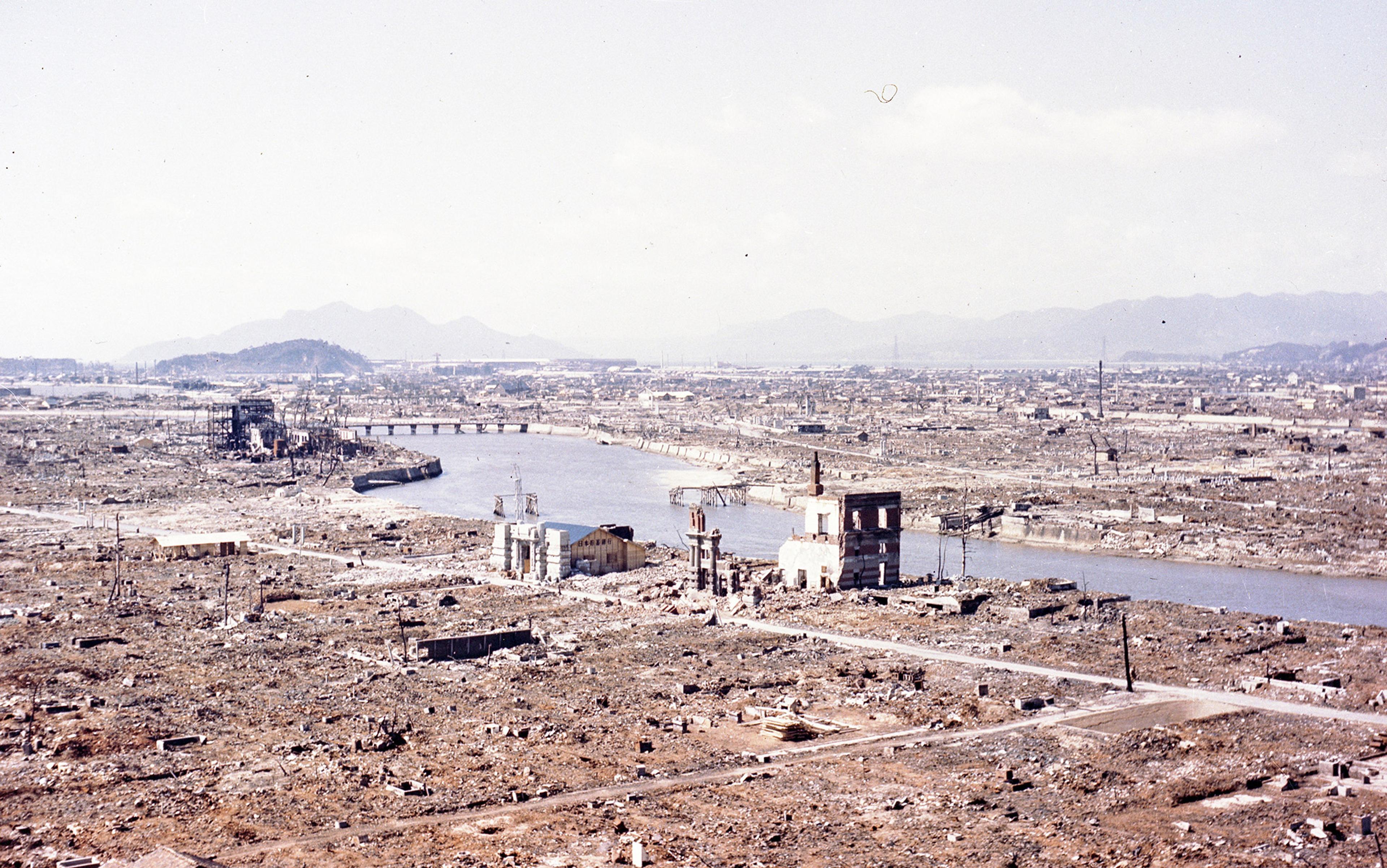

They departed in a hurry, suddenly, unannounced. Fleeing. Leaving behind a terrible mess, the already-mutilated earth further scarred with the broken lines of trenches, dugouts, fortifications and other military structures that cut into the forest floor, its topsoil and subsoil. Having plundered and wreaked havoc in people’s homes, they abandoned their improvised ‘command centre’ and ‘military quarters’, where command and control no longer made sense.

The retreat of the Russian troops from Chernobyl occurred on the last day of March 2022, just five weeks after the area had been occupied. This surreal set of circumstances is far from idiosyncratic. Everything that concerns Chernobyl – the name of the place long since synonymous with the event – is part of a miniature postapocalyptic laboratory for imagining ‘the world without us’, a global future where there is no place for human beings. Such a future may be bemoaned or, with a good measure of misanthropy, celebrated: finally, Earth will have been cured of humans, who – cancer-like – eroded its climates and ecosystems.

We cannot decide on the habitability of a place. Such a decision is made by that place itself

From all sides, the East as well as the West, the ideological investment in presenting Chernobyl as a nuclear phoenix who comes back to life from the ashes of fallout has been tremendous. A repressed trauma of planetary proportions, it took about one generation for the narrative to shift, for tourism and agricultural production to develop there, and a little less than two generations for the exclusion zone to be converted into a military theatre.

Yet, the repressed implacably returns, even if (especially if) in its comebacks it sidesteps conscious representation and imprints itself directly onto the flesh, onto sentient and exposed bodies. This is what the frenzied abandonment of Chernobyl – the site of the absolute abandonment – by the Russians signified: we, those living in the 21st century, cannot decide in a sovereign fashion on the habitability of a place, a region, even the entire planet. Such a decision is made by that place itself, or, more exactly, by whether or not it can still be a place for the human and other-than-human populations it welcomed in the past.

The date was 24 February 2022. Under leaden-grey wintery sky, a column of tanks and armoured vehicles carrying 1,000 Russian servicemen crossed the Belorussian-Ukrainian border and rapidly moved further south, toward the town of Prip’yat and the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. Kicking up radioactive dust, heavy military equipment and its crew rolled along the most contaminated area, that of the Red Forest. No precautions were taken to keep the soldiers safe: they wore no protective gear, which would have prevented them from being exposed to radioactive particles, the timeless remainder of the 1986 nuclear accident that destroyed the plant’s reactor Number 4 and released tons of contaminated debris into the atmosphere.

On day one of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Chernobyl was among the very first territories ‘taken’ in the still-ongoing war. As if a nuclear disaster site can be seized – as if it does not seize whomever and whatever is in its vicinity in advance, dictating its own rules of a deadly game. The occupying powers will discover the limits of mastery and of habitability the hard way, once they start experiencing the unmistakable symptoms of radiation sickness. But, for now, they are exhilarated with an easy victory, having negotiated the surrender of dozens of Ukrainian national guards and of the workers who maintain the nuclear power plant. And, just as they are settling into the place, or non-place, that will be unfit for human habitation for at least another 20,000 years, Russian soldiers are busy with an absurd task: digging trenches in Chernobyl.

Why trenches in Chernobyl? Within the twisted logic of Vladimir Putin’s war, the strategic rationale was evident. The exclusion zone, in particular the territories adjacent to the exploded reactor, were to become the staging grounds for attacks that would be invulnerable to Ukrainian counterattacks: who, after all, would return artillery or any other sorts of fire emanating from there? More or less the same reasoning organises reckless military activities around the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, the largest of its kind in Europe.

Like a Russian doll, madness was ensconced within madness: digging trenches in radioactive soil

What the generals of the invading army did not count on was a mutation in the structures and processes of geopolitics that, akin to other mutations provoked by radiation exposure in generations of the living, raze tactical planning to the ground, leaving it in ruins. Saturated with radioactive elements, the earth, which Russian soldiers treaded and excavated, acquired an uncanny agency: it dictated the course of events, shifting frontlines, expelling or repelling those who dug into it, letting them win or making them lose. Although the terrain with its uneven texture and accessibility always determines (or, at a minimum, co-determines) political borders and the outcomes of battles, in Chernobyl this determination reached its peak intensity. Henceforth, we will need to understand geopolitics in a literal key, as the politics of Earth itself, not imposed upon but flourishing from the earth, irreducible to territories and domains, real-estate plots or regions of a state.

Trench warfare is the hallmark of the First World War with its stalemates of artillery crossfire. It persists in the Second World War, but loses effectiveness due to aerial bombardments, among other kinds of new lethal technologies and modes of combat. Digging trenches at a nuclear accident site is more anachronistic still. Temporalities get scrambled in Chernobyl, starting on that fateful February day: a symbol of warfare from the beginning of the 20th century, 19th-century imperial ambitions, the nearly atemporal effects of radioactive materials, and 21st-century live combat. History itself in the shape of the deranged swell of a single disaster, as Walter Benjamin has it, manifested itself in a flash in this deadly convergence of disparate temporalities. Like a Russian doll, madness was ensconced within madness: digging trenches in radioactive soil within Putin’s claim that a country with a 44 million-strong population and internationally recognised borders did not exist within the making-Russia-great-again refrain within a total lack of concern for environmental and human casualties of imperial hubris within…

Entrenchment is stubbornness raised to the nth degree, leaving a foredoomed confrontation as the only plausible option. In no small measure, it stems from the refusal to listen to any other arguments, not least those raised mutely but all the more palpably by the earth itself – by the planet and the soil alike. Lest we harbour any illusions, it is not unique to the ruthless war that Putin’s Russia is waging on Ukrainian soil. Rather, the madness of entrenchment is engrained in the technoscientific framework that is responsible for the development of the ‘peaceful’ as much as the ‘military’ atom and, deeper yet, in the dominant and domineering relation to Earth.

Even as the climate breakdown is upon us, we witness all around us suicidal attachment to the old destructive modes of thinking and technologies, often in the guise of a green energy transition and other reassuring discursive tricks. Despite evacuation orders issued by Soviet authorities a day and a half after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, we are yet to leave Chernobyl – or everything that it stands for as a culmination of Western metaphysics, its theoretico-practical notion of energy, of subjectivity and objectivity, of matter, of the earth. The entire humankind is entrenched there in the double bind of the absolute necessity and the perceived impossibility of leaving it.

Soil. Location: Exclusion Zone, Chernobyl, Ukraine. Radiation level: 1.7 Ms/ hour. Rayogram, 24x36 cm, Pigment print on RAG Paper. From Chernobyl Herbarium©Anaïs Tondeur, 2022

The trenches of Chernobyl are not only physical, but also metaphysical. They are the palpable effects of metaphysics and its relation to matter, to Earth, to the physicality of existence. The actual episode of the Russian occupying forces digging them has put into practice much that is troublesome in the overall treatment of the world and, most notably, of what we still refer to using the old-fashioned word ‘nature’. Rather than merely symbolic, the act is a stark and exaggerated expression of behavioural vectors that precede the ‘event’ of Chernobyl, and that continue their movement largely unperturbed after this ‘event’.

The four vectors of metaphysical entrenchment are most acutely felt in Chernobyl’s amplification of the planetary disaster. In a shorthand, these other trenches can be designated as follows.

- Trench #1: energy

- Trench #2: elemental dominion, especially geo- and climate engineering

- Trench #3: environmental separation (self-subtraction from the environment)

- Trench #4: extraction

At many points, the entrenchments intersect and reinforce each other:

Energy – extraction

Our unquenchable search for energy splits the atom, getting a hold of, appropriating for but an instant, the potentialities it contains in the process of nuclear fission. The extractive-destructive energy paradigm is not limited to burning fossil fuel; what it wrests from things is their potential at the expense of their physical integrity and actuality. Official consideration of nuclear energy as ‘green’ fails to notice how our thinking and practices get caught in the nets of this harmful paradigm.

Elemental dominion – environmental separation

A non-negotiable precondition for the illusion that we can manipulate the elements and the climates that envelop us is our sense of separation from the environment. It is then that the earth and the air, the solar blaze and the oceans, present themselves in our distorted optics as objects of a planned alteration and control. In the long term, the ‘enhancement’ of topsoils or their cleanup in the case of radioactive contamination impoverishes them and contributes to a further spread of radioactivity, aggravating the very problem to which these were meant to be the solutions.

Energy – elemental dominion

Rather than work with the elements in a synergy that would gift us with nondestructive energy (elemental; not simply renewable), we approach it as a resource to be appropriated within the scheme of our elemental dominion. A scarce resource, subject to contested claims, that energy which does not germinate in synergy sparks wars, due to the objectification of its sources.

Environmental separation – extraction

Our feigned separation from the world is the first extraction – the degree zero of extraction, one might say – constituting our self-subtraction from the living and liveable environment. This subtractive extraction portends death, if not suicide: collective or species-wide. All subsequent extractive operations repeat with regard to the elemental sphere the first self-extraction of the human from the environment.

Energy – environmental separation

The energy drawn from our separation from the world and from the ensuing oppositional stance, in which the world is reduced to an object (particularly, the object of appropriation), is the energy of negativity. It invariably operates with the minus sign: scarcity, crises, a struggle over dwindling resources, the devastation of beings in their physical integrity. The practice of procuring and utilising such energy is imbued with negativity, and projects our separation from the world onto the world at large. Henceforth, the environment comes unglued from itself, fragmented into bits that are grasped as resource-laden objects and that are, therefore, already dead or deadened.

Extraction – elemental dominion

Extraction is the logical consequence of elemental dominion: we take what we deem to be properly ours, as the unquestionable owners of the globe, of its surface and depths alike. But what exactly is it that ‘we’ do? When it comes to fossil fuels, mined and burnt, we throw massive portions of the earth’s contents up into the atmosphere, wreaking havoc in the world of the elements. By breaking the atom to extract energy from its core, we do not get hold of anything, except for radioactive waste, which gets a hold of us, posing the dilemma of storage over time spans of thousands of years. Elemental dominion does not translate into anything securely maintained, guarded as property, as a rightful possession. Instead, it justifies the ever-growing unleashing of negativity, of the power of the negative, which – masquerading as the only possible source of energy – annuls a liveable world and ourselves in it.

In Voices from Chernobyl (1997), Svetlana Alexievich chronicles through her conversations with survivors how they were engaged in the ‘new human yet inhuman task’ of burying contaminated topsoil deeper in the earth or entombing it under concrete. A teacher relates to Alexievich that, in early June 1986, ‘the director of the school suddenly gathers us and announces: “Tomorrow, everyone, bring your shovels with you.” It turns out we’re supposed to take off the top, contaminated layer of soil from around the school, and later on soldiers will come and pave it.’

A ‘liquidator’, one of the hundreds of thousands of people moved to the vicinities of Chernobyl from all over the Soviet Union in order to mitigate the effects of the disaster, confirms this narrative: ‘I saw a man who watched his house get buried. [Stops.] We buried houses, wells, trees. We buried the earth. We’d cut things down, roll them up into big plastic sheets… I told you, nothing heroic here.’ He continues: ‘We buried earth in the earth. With the bugs, spiders, leeches. With that separate people. That world. That’s my most powerful impression of that place – those bugs.’

As a result of the Chernobyl disaster, the earth became a grave for the earth, the soil buried further down in the soil. Digging up trenches in that place, or non-place, is unburying the earth, which is tantamount to unburying the undead in light of the undiminishing effects of the radioactive particles, with which the soil of Chernobyl is laced. The trenches, dug in the earth that used to serve as a grave for Earth, are also graves – in the first instance, for their diggers. Although this activity undoes the one initiated in the early post-disaster days, it is equally absurd and deleterious for those engaged in it.

Commanders in the army play with fire, in the most literal sense of the expression

Disturbing and inhaling radioactive dust, the diggers follow an injunction that remains oblivious to the earth in its elemental character. The silent teaching of Earth, further magnified by radioactivity, is that it cannot be dominated or controlled, notwithstanding our illusions about terraforming or geoengineering. But it is by means of their attempted domination of Earth that the trench-grave diggers of 2022 try to dominate others, including militarily.

In its strategising, both military and civilian leadership outmanoeuvres itself. Trenches in Chernobyl make this painfully clear: they do not pit safety against danger, but safety against safety, or the acknowledged danger of war against the unacknowledged danger of exposure to life-threatening levels of radiation. By creating bunkers and dugouts in the exclusion zone, the troops are presumably protected from enemy fire, but they are exposed to the invisible enemy – the radioactive particles they inhale and ingest. By using the vicinity of nuclear facilities, in Chernobyl or more recently in Zaporizhzhia, as a military theatre of attacks that preclude counterattacks, commanders in the army play with fire, in the most literal sense of the expression.

Why do we find such shortsightedness in the midst of an addiction to strategies and calculations, game theories and algorithmic simulations? On the political side of things, democratic and authoritarian regimes are in a remarkable harmony: the former, blind to lasting consequences of decisions due to the four- to six-year electoral cycles; the latter, due to the dictators’ egotism and their desire to stay in power at any price. On the side of pure strategy, a vast blindspot develops when one puts one’s total faith into calculations that, by definition, cannot deal with the incalculable: history-defying lengths of time, irreversible damage to ecosystems and their inhabitants, and the like. Within the framework of folk psychology, radiation’s invisibility accounts for the ease of forgetting all about it and for letting it drop, if temporarily, from the field of our concerns and calculations.

Without a doubt, in addition to the three I’ve just cited, there are other mutually reinforcing causes for the shortsightedness of military and civilian strategies, as far as radioactivity is concerned. The outcome remains unchanged, however: excessive radiation does not go anywhere, no matter how much we ignore it. Like trauma (or as trauma), it persists behind all the perceptual, political, calculative and other façades that occlude it from us. But, in the strongest rebuke to idealism and its commonsense variations, the trauma of radioactivity does not stay neatly contained behind physical and psychic walls; it breaks through each and every barrier. Then, previously drawn-up plans suddenly change: human settlements in the fallout zone are evacuated, and armed forces retreat from occupied territories. (And what is the meaning of ‘occupying’ a site in a physical or, worse yet, military mode of occupation, when it does not admit anyone into its midst?) Entrenchment has externally imposed spatiotemporal limits. Sooner or later, the place of refuge that trenches seem to provide starts exuding what Immanuel Kant once called the perpetual peace of cemeteries.

On the run from Chernobyl’s exclusion zone, Russian troops left behind many of the items they had stolen from the Ukrainian population. According to one report in The New York Times, ‘in a bizarre final sign of the unit’s misadventures, Ukrainian soldiers found discarded appliances and electronics on roads in the Chernobyl zone. These were apparently looted from towns deeper inside Ukraine and cast off for unclear reasons in the final retreat. Reporters found one washing machine on a road shoulder just outside the town of Chernobyl.’ Come to think of it, the roadside discovery of looted and abandoned appliances is not so bizarre. After five weeks in Chernobyl, it’s likely that the stolen appliances triggered alarms on Geiger counters. Once these measurements were performed on the soldiers’ clothes, food and belongings (including the stolen ones), they were promptly discarded. The temporarily challenged supremacy of abandonment is restored.

What is abandonment, though? How does it work? Above all, how does it work against our conscious and unconscious tendencies toward entrenchment?

In 1986, Chernobyl was abandoned, as it will be again, albeit in very different circumstances, in 2022. What is happening there (or, on the contrary, has ceased happening) seems too obvious to state: Chernobyl’s previously utilised sites and inhabited places have been largely deserted by human beings. But a lot more is going on beneath the veneer of obviousness. Before abandoning the no-longer-liveable parts of the world, human beings are constituted in their very being by abandonment. In Being and Time (1927), Martin Heidegger raises a poignant question regarding this constitutive abandonment:

What is it that so radically deprives Dasein [literally, being-there; human existence] of the possibility of misunderstanding itself by any sort of alibi and failing to recognise itself, if not the forsakenness [Verlassenheit] with which it has been abandoned [überlassen, Überlassenheit] to itself?

That is, the clarity of understanding comes not from the logical exercise of ‘clear and distinct ideas’, à la early modern philosophy, but in the merciless light of our finitude. Our abandonment to ourselves makes us who we are, because in this condition we are confronted with mortality not as an abstract notion, not as one vague possibility of many, but with our impending death.

The devastation where this abandonment takes its place is a nod of consent to the sweeping power of nothingness

The lucidity, with which I face myself as mortal, radically individuates me, Heidegger argues. Now, since human existence is not really separate from its world, doesn’t the same terrifying clarity arise when we find ourselves face-to-face with the demise of that world? Should we not recognise ourselves, the future corpses our bodies will become, in the mutilated remains and the ruins of abandoned towns? This is, in fact, the realisation that we come to after the physical evacuation of disaster zones or contaminated areas. In addition to being abandoned to ourselves, according to Heidegger, human existence is abandoned ‘to a “world” of which it never becomes master’. The limits of mastery are delineated by the unruly effects of technology, which leads a life of its own outside the parameters that its inventors or users have set for it. Contemporary ruins are the material traces of that limitation, which double our constitutive abandonment: to ourselves and to the ultimately uncontrollable world.

There is, also, a third kind of abandonment in Heidegger’s work – the most difficult but also the most relevant. As he put it on 8 May 1945: ‘The being of an age of devastation would … consist precisely in the abandonment of being.’ The abandonment of being does not let beings be; the devastation in which this abandonment takes its place, or non-place, is a nod of consent to the sweeping power of nothingness, a nullification that is worse than destruction, from which a new life, a new growth, a new vitality, however tentative and fragile, might have sprouted.

Currently, a multipronged battle is being waged not only over territories and their political or military control but also over the meaning of abandonment or, more accurately, over its semantic frame in the environmental context: destruction or devastation? Is the massive damage done to ecosystems, biodiversity, breathable air, water and soil a destructive prelude to renewed vitality? Or does it signal a devastating self-negation of the human, of its world, and of worlds that are not and have never been within the scope of our power and control?

There is little, if any, coincidence between the two battles on the political-military and the ideological fronts. Although the safety of the nuclear site is of vital interest for the Ukrainian people – the interest that is being exploited as part of nuclear terrorism by the Russian regime in other locations, such as the Zaporizhzhia – prior to the war, Volodymyr Zelensky’s government related to the exclusion zone out of purely economic considerations. Back in 2019, Chernobyl was to be ‘rebranded’ as a safe tourist site. Nevertheless, in the lightning-fast Russian occupation of, entrenchment in, and withdrawal from Chernobyl, the normalising logic and its accompanying repression were illuminated with respect to both their workings and their spectacular failure. Trenches in Chernobyl have provided a crucial answer to the question of abandonment. The question is whether we will listen to and remember this answer.