Hatred is different from paranoia. Hatred can engulf a nation in a millions-strong frenzy of self-righteousness. Hatred can be held by one person all the way to the grave. It can be suddenly relinquished (sometimes beautifully); or it can just wear itself down like an overused axe blade.

Paranoia, on the other hand, is a matter of self-defence: it assumes malice on the part of the other. My department chair, Torrone, wants to fire me. He’s planted a graduate student in my Latin class. I’m thinking primarily of schizophrenic paranoia, such as my own. It is a red-hot drive that inhabits an individual and feels like it wants to take over his mind.

When I’m paranoid, I travel on the horizon’s edge, the line between all and nothing, between ‘them’ and me. That student is to observe me, to report back to Torrone. I travel that edge alone. Aloneness is of the essence. Paranoia has nothing to do with loneliness which, after all, seeks union. And it’s seemingly forever. Paranoia doesn’t dissipate, run down, run out of steam. Logic is almost always pointless against it: I can no more will my paranoia away than I can will my thinking straight. Just yesterday I saw Torrone, out walking, all these years after the incident. I ducked down a side street.

And paranoia is far more complicated than hatred. That’s because paranoia is a whip-snapping combination of anger and fear. It’s often a reaction to a perceived slight – one that suddenly seems to hide a conspiracy behind it. A conspiracy involving distant relatives, creatures from outer space, even God. Paranoia hatches involved, unbelievable, soap-opera-like plots that the mind readily embraces with stunning naivety.

Paranoia is sneaky, secretive; it hides inside, often known to the paranoid individual alone. Thus its expression sometimes comes as a complete surprise to others. It can be like a crocodile lying low in a watering hole for hours, only its nostrils showing, until with great splashing and lunging it suddenly takes down a water buffalo – or a gazelle.

Starting out as fear of another’s malice, my paranoia morphs into layers of anger over fear, over anger over fear. It doesn’t occur to me to question the validity of the malice or the appropriateness of my reaction. I don’t recognise that the problem is largely inside me, that I’m projecting it onto someone whom I’ve judged out to get me. I have signs on the bulletin board behind my computer, to alert me at just such a time: ANGER IS A SYMPTOM and ASSUME THAT IT’S PARANOIA. But in the heat of the moment, I find the idea that I might be paranoid, well, ridiculous.

Words, tones of voice, facial and bodily expressions, apparel, any way at all that humans seem to be communicating, are at the heart of it. Of course, it’s never possible to understand another’s modes of expression perfectly. We all mishear, misread and misview to some tiny or huge extent. So we’re all sometimes confused, miffed, frightened. Some of us solve the problem by crediting good intentions to the other. Some of us ask for clarity. Some hold a simple grudge that will likely fade. Some misinterpret through habits of sarcasm and cynicism.

A few of us become paranoid.

I recently invited a friend to my house for tea. This friend has given to me from her heart for decades. To that invitation email she replied that her sister was in town. ‘No time for tea!’ she wrote cheerfully.

I heard in those words: ‘No time for YOU!’

Then my paranoia added, no time for her to go across town to my modest digs, no time for someone of my socio-economic status, no time for someone of my politics, no time for a schizophrenic.

Paranoid ideation grows like cauliflower, in all directions. One detail makes a flower for another to grow on, and so forth.

My friend was laughing at my smallness. She was flicking me off like a bug: ‘No time for you!’ I could see her and her husband, sitting at their kitchen table, snickering about me. They were pushing me out of their lives.

Paranoia is a Biblical dilemma, a mini-war between good and evil. My good, their evil. Satan lurks

Anger flowed through me like an open faucet.

I wrote her back an email of hurt and anger.

It never occurred to me to remember that she loves me.

Love and trust and their opposites are the crux of it.

Paranoia is distrust. Even more – it’s the opposite of belief in others’ goodness. It’s an assumption of malice.

Paranoia is a Biblical dilemma, a mini-war between good and evil. My good, their evil. Satan lurks.

When I’m paranoid, I hold the conviction that I’m the only good person at hand, mocked by a supposedly dear friend invited for tea; made a fool of by a student who beguiles me with youthful sweetness into giving him a better grade than he really deserves and then surely berates me on the anonymous course evaluation; taunted by a chairman who I am convinced will not hire me again next year out of envy of my recent book.

I take 15 mgs of aripiprazole and 50 mgs of thioridazine at night, and 10 mgs of aripiprazole and 25 mgs of thioridazine in the morning.

It’s not clear to me how much good they do.

Two weeks ago, I went to a cocktail party in the school of social work at the University of Denver. After the socialising, Voices (2014) – a documentary about three people with debilitating schizophrenia – was shown. I’d been encouraged by the chair of a mental-health board I sit on to speak briefly afterwards, as someone living successfully with the disorder.

It was hard. I hope that didn’t show. It was hard because I’d just been surprised by intense, cold, conspiring disdain from every person I had contact with during the cocktail hour – both people I knew, admired and felt safe around, and people I’d never met before. Wearing heels and a nice dress, holding a drink and standing in a small circle of chatty guests, I felt paranoia hit me like an assault. It’s dirty, mean, lowdown; it shrieks off-key; it’s interrogation in a room with only a table and a light bulb.

When I’m paranoid, I’m forced to lead a double life in the face of silent conspiracies: I can never let my enemies know they have a grip on me. Even though we are ‘alone’, those of us with paranoia often have good social skills. After all, we have to appear calm, pleasant and interested in the conversation and the plans at hand, all the while pinned to a dissection board. This is the real reason I said, above, I hope that didn’t show. It’s imperative to avoid being victimised by the enemy.

I follow orders from distant galaxies, from the President, from my dead mother. The orders come from a barking dog. The TV. Email

That’s the low-grade stuff. I’m probably somewhat paranoid, a little on guard and on edge, at all times. Perhaps once a week (the tea invitation and the cocktail party) I experience paranoia severe enough that I make a note of it in my journal.

Then there’s the big stuff.

A crafty, malicious drive from outside takes control of me.

Within moments, or hours, or weeks, or longer, the drive and my awareness of it are all that’s left.

It’s a drive to make me follow orders from distant galaxies, from the President, from my dead mother. The orders are received through the air conditioner. Or a barking dog. Or the TV. Email. I’m to follow orders to ensure my protection, my evolution, or a nod of approval from a supreme being.

Because certain people are out to harm, even kill, me.

The orders I receive are to:

avoid those people;

tell a carefully chosen person that I’m about to be harmed;

hide;

don’t tell the police, because they’re among the ones out to harm me;

don’t tell people who say they care about me: they’re among them, too;

hide;

be angry, because this is all so wrong

so Orwellian.

The first time Channel 9 (the local NBC affiliate) broadcast specifically to me was late at night. There were no other sounds in my apartment building. The newsman spoke directly to me, eyes to eyes, through rays. I remember his silence. I was told I was evil, inexpressibly bad, not fit to live. The rays fastened me to my sofa. I couldn’t even get up to go to the bathroom. Guilty, afraid, but above all bad, evil. The world was silent, and I was alone. I didn’t feel alive; I felt like metal.

I drank over it.

The next time I was ‘called’, it was also far into the night. Evil Ones gleaming with poison, from a faraway galaxy, filled me. They gave me metallic rules stamped into my head. The rules stated that I had to become completely mad, couldn’t ask anyone for help, couldn’t step on cracks, had to kill myself. They commanded me to get up off my sofa. I did. That’s all there was to it. I felt robotic.

I knew nothing about the Evil Ones except that their ship was poised high overhead, and gigantic. I recall its grayness and its silence. The Evil Ones ordered me to put on my bathrobe over my nightgown, turn off the TV, go out the front door, and take the elevator down. Once outdoors, in the darkness, the dewy air and silence, I was told to walk without stepping on cracks; walk down to the filthy alley behind Broadway, a seedy street of Denver six blocks away. I turned into the alley and plodded through it, block after block, robotically obeying the Evil Ones’ order to set myself up to be killed.

I met no one, not a murderer, not a policeman. Not a kind person who might call the police to come and take care of me.

I remember feeling otherworldly, like the evil ship hovering above. I walked on.

I circled, eventually arriving home. The Evil Ones faded away for the night. My apartment felt small and familiar again. Somehow I felt less alone in it. I slipped off my bathrobe and fell into bed to sleep.

There’s always an element of truth hidden somewhere in a paranoid plot. The truth of this story is that I wished to kill myself that night. And there’s always a shifting outward of responsibility. Some part of me wouldn’t, couldn’t admit to seeking suicide; so it set up a scenario with an ‘outside’ force, the Evil Ones, whom I was to ‘obey’ into death. But, in fact, no human agent materialised in the alley to kill me. In consequence, the Evil Ones were stripped of much of their power and faded. I went to bed.

It’s the inevitable question.

Does every person who has psychotic paranoia have the potential to murder as well? To follow, or obey, a plot all the way, to the very end?

I don’t know.

Does every human being who isn’t psychotic have the potential to murder? To kill the enemy aiming at him? To protect a child? To get even with a Hitler?

I don’t know.

Once, I did wish to kill a particular person.

That day, I was so full of paranoia that I was enduring it moment to moment.

Paranoia of this intensity pushes and shoves you, stumbling ahead. There seems no way out. If the paranoia becomes unbearable, it must be sprung, ripped open, broken down. The spectrum of action that must be taken can include harming another person, just as it can include killing oneself to escape from dangers only imagined.

Not only is the paranoia unbearable, its veracity is unquestionable. After all, how can I question a drive that has taken over my whole self? There’s nothing left with which to question the truth of my suppositions.

I want to shout, that person is harming me, dreadfully; is a snake coiled around me; is poised to kill me. What do you expect me to do but defend myself?

This is the survival instinct at work, in the lone individual.

In fact, nearly all paranoid people who kill act alone. Because they could not be anything other than alone.

Right and wrong are not of the essence.

That day, a kind woman was startled by my face when I came in her door. I was shaking. She went up to me, put her hands on my shoulders, and said: ‘Go, lie down. Pull yourself together. You need your medication.’ Her steadiness, her earnest warmth, were the opposite of paranoia.

She was my mother.

We never spoke of it.

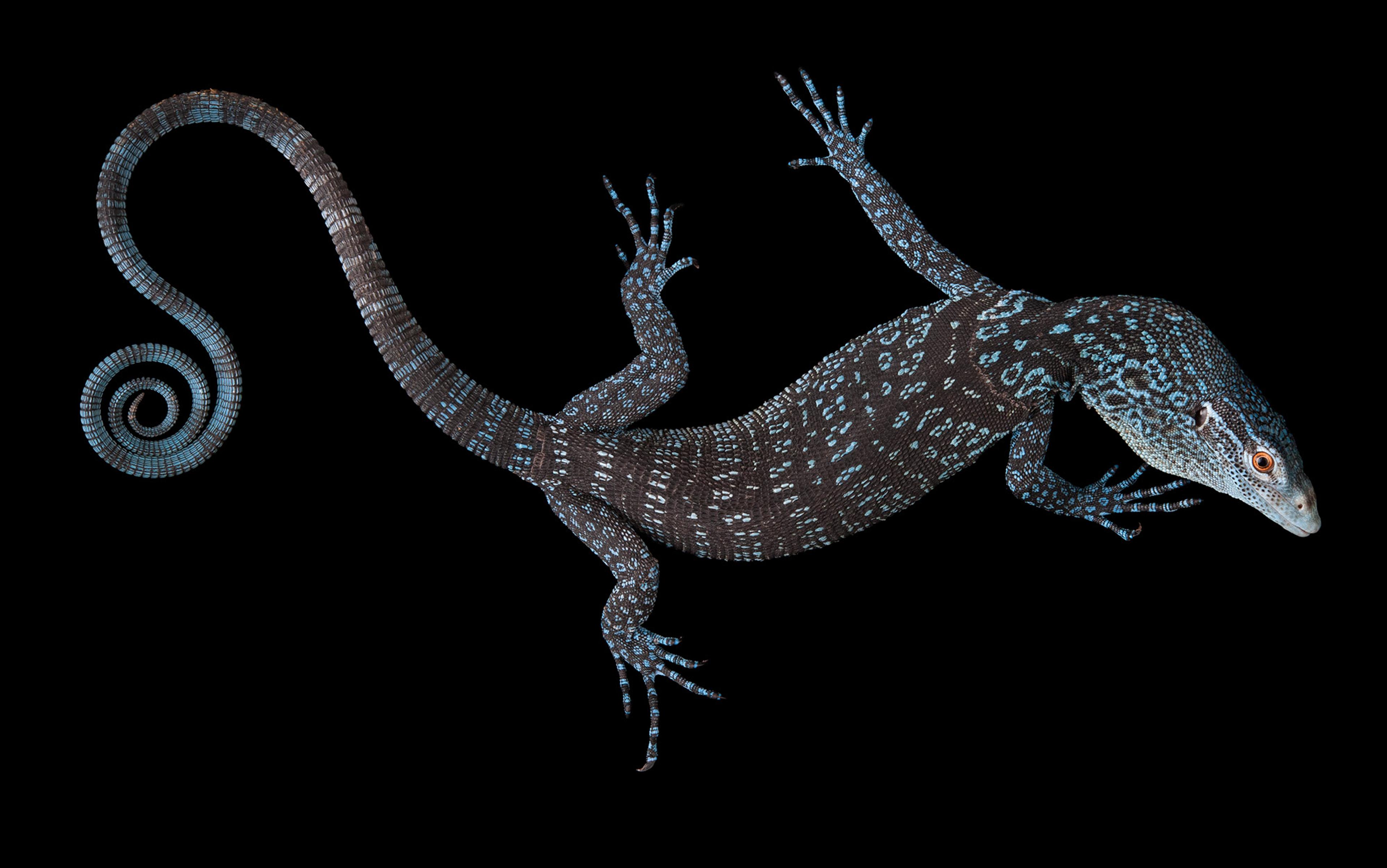

The greater the imagination, the more elaborate the paranoia: a giant lizard that feeds on your strength and twists it back against you

When I got up from that rest, my oppressor’s coils had loosened somewhat, the fangs retracted. I was back here, on this side of the line.

Could I have done it?

I don’t know, truly.

Where does paranoia come from? Looked at it from the inside and close up, it appears to come from imagination. Imagination is fundamentally human. At its best, imagination gives people the enormous gift of healthy creativity. But at the opposite reach of imagination’s wand is paranoia. The greater the imagination, the more elaborate the paranoia, like a giant, chimerical lizard, seeming to feed on your strength and twisting it back against you.

An image I have of paranoia comes from a carefully guided/guarded trip I took to Soviet Russia in 1964, a few years before I became ill with schizophrenia. The second morning we were in Moscow, I slipped away from the tour group, because, being 19, I thought it would be fun to see if the KGB would follow me. I wandered, then took a bus whose destination in the Cyrillic alphabet I couldn’t read, and got off after about an hour (apparently not followed). I was surrounded in all directions by miles of identical, gray, concrete apartment buildings. I couldn’t ask the rare person I came across for directions to get out, because almost no one in the USSR spoke English. I walked – rather as I was to walk and walk, psychotically, through the alley in Denver 20 years later. In Moscow that morning I felt there was nothing alive, and I was boxed in as far as I could see. It literally was totalitarianism I was witnessing; just as it is totalitarianism that I experience in the midst of my paranoia.