Recently, a friend offered to put up some shelves for me. As we drove to the hardware shop, we got to talking about relationships and he mentioned that he was polyamorous: though he lives with his primary partner, he is free to be with other women too. He told me how once, by chance, he’d found himself dancing in a nightclub with all his lovers: tickled by the memory, he tapped a beat on the steering wheel.

‘That’s cool,’ I said, smiling.

Despite his being a new friend, I already knew about this fluid lifestyle; he’s attractive and easy with his body, so it didn’t surprise me. I’m a relaxed individual, too. I had no problem with what he was telling me, only I found myself discomfited by our conversation. I wondered how it worked for him. Was it consensual? Does his wife do the same? Aware of a heat rising in my cheeks, I wound down the car window. ‘Doesn’t it affect your intimacy?’ I asked. Having recently gone through a divorce, intimacy was something I wished to handle with care. I was embarking on a new relationship that was wonderful, but tender, after all that had been lost.

‘No,’ my friend said, ‘it’s the complete opposite.’ If anything, their open relationship made him and his partner closer, plus they could each pursue their needs without risking a breakup. Polyamory embraces an open relationship that relies on transparency and consent, and can be a safety net for those who find monogamy unnatural: like taking a prophylactic drug, it addresses the problem before it happens. It’s a nod, perhaps, to our permissive society, but a development, also, from our parents’ more chaotic experimentation in the 1960s and ’70s. I’d seen the sparky TED talks by Esther Perel, the couples’ therapist and all-round relationship guru, and I’d read her most recent book, The State of Affairs (2017), where she argues that in light of rising infidelity in Western cultures, it’s time to take a fresh look at the topic. This made sense to me on a cerebral level but, surprisingly, in my friend’s car, I was finding it difficult to breathe.

‘I could never do that,’ I said, failing to keep the defensiveness from my voice. ‘I just know for me it would not be possible.’ I told him about my upbringing with a father who had multiple partners, kept secret during my parents’ marriage; the shocking nature of some of his transgressions. My father was long dead – a protracted suicide through alcohol poisoning – and yet, in that moment, I felt his presence beside me, taking up most of the passenger seat.

‘That’s a lot to contend with,’ my friend said, holding my gaze. There was a knowing look in his eyes that shouted: And it sounds like you’re still pretty hung up about all this!

My mind ran in circles, dizzy with self-doubt. I was reminded of the parties in my youth, mass sleepovers, girls sharing baths, boys sharing my bed. My friends being open about their sexual fluidity, and my same response – a kind of heartache, a shut-down, a closing-off. Me, old-fashioned, uptight, unevolved? My father was there again, morphed into a head on my friend’s shoulders, such a similar easy smile, the same pleading ‘love me’ eyes. Why don’t you just chill out? I gripped hold of the door handle and searched the streets for something familiar. Where are we?

That’s when I caught a glimpse of myself in the wing mirror, a woman now, not a girl, my father absent. Pushing the muss of windblown hair from my eyes, I also saw clarity and a fierce, different kind of knowledge – born of the pain that comes with knowing what it is to betray and have someone betray me, its constant distraction, how it clouds and distorts, cutting you off from those you love. How hard I had worked to put that behind me. I felt myself expand again into the passenger seat. Turning back to my friend, I pointed out a good place to park.

Later, my mum laughed at the end of the phone: ‘What a sexist load of twaddle. It might be all right for your friend who doesn’t have children, but can it ever be equally consensual? Sounds like an excuse to shag around –’ and I wondered why I’d been so thrown after all these years. My own private joy of intimacy, so hard-won, tested momentarily by this man, so like my father in his conviction that his way was better.

My father was unfaithful, a philanderer, a serial shagger; there are many words for what he was when terms such as ‘consensual nonmonogamy’ or ‘polyamory’ were not yet in popular use. Adultery is a shameful word, a transgression from the sanctity of marriage; like ‘cheating’, ‘infidelity’ and ‘unfaithfulness’, it is not morally neutral. It derives from the Latin word adulteritas, meaning contamination. It’s no surprise that my father lied about his liaisons in his 12-year marriage to my mother, though he once boasted to his sister – true or false – that there had been 500 affairs. He took pride in being humorously subversive, doing nothing to hide his inappropriate comments to passing women when my brother and I, just children, watched wide-eyed from the back seat of his fancy car.

As a young man, my father was a sexual magnet, shining and beguiling; tall with long limbs and a film-star presence, thick blond hair, eyes too big, and too blue. As a toddler, he was proudly pushed around in his pram by a mother who was made for the stage but thwarted. She took great pleasure in the attention this beautiful boy awarded her. My father was more ambivalent. He sought out attention, yet found it overwhelming; however, soon he came to rely on it, as if it were a strange kind of nourishment.

I’ve spent much of my life trying to make sense of my father. Was he Cupid’s victim, wounded by an incontinent desire and too insecure to commit wholly to one woman? Or in light of our culture’s tenacious and unrealistic expectation of romance – ‘the grand ambition of romantic love’, as Perel puts it – did he simply flee from love’s loaded responsibility? My parents were teenagers when they met, children of the 1960s, romantic and idealistic. They barely knew themselves.

Except that my father’s self-serving behaviour was off the scale. He would have been forgiven for a simple flirt or one-off fumble, but he was like Pan, the horned god, led by his need for conquest, speaking in riddles so as not to be found out. When my mother sensed something was wrong, when her instincts cried out for the truth, he called her paranoid. For years, I found it inconceivable that he could return each night to make love to his wife having come from the embrace of another woman. It wasn’t just my mother he hurt, or any number of the women he made promises to, their marriages broken. Were there pregnancies? Children? The tentacles of betrayal crept everywhere.

As a child, I thrilled to the story of how my dad attempted to reach us when my mother was in labour with me. He’d been at a meeting up North. In his Citroën SM, he drove as fast as he could down the motorway, blind to the fact that he was running out of petrol. On the outskirts of London the fuel gauge hit zero. He glided to a layby, got out of the car and ran. He ran all the way, he told me, to get to us in time. I imagined his long legs in narrow trousers, hair flapping crazily in the wind.

Did I also bathe in the fluid of his betrayal? Did the agitation course through my veins?

Yet in my mind’s eye, when my father finally arrived at the hospital, I see how he avoids us; how the simple tranquility of a mother and her newborn, after all that they’ve experienced, throws his shame into relief – he is there, but also not. How could he be fully present? She was the mother of his child, and yet, as we were to find out later, my father’s body had been elsewhere. His mind, his hands, his thoughts, his heart. Whatever. This level of deceit draws a new path, another landscape, stained with guilt. We feel bad about ourselves when we lie. Withdrawing, avoiding the lover’s eye, we see fault in order to justify our behaviour – ‘Look at what you’ve driven me to.’

My mother didn’t know it at the time, but, then again, of course she did. We are all instinctive beings. When I was in utero, my mother’s spirit was sullied by him. Did I also bathe in the fluid of his betrayal? Like a child born of an addict, did the agitation course through my veins? My origin myth. Subservience to a tantalising absence.

Only weeks later, my mother was up at night, waiting for my father. She stood by the window with me in her arms. Why was he so late? To add to her unease was the fear that whatever she felt would pass through her body to me, her precious daughter, heart to heart; that her tears might drop onto my tiny face as I searched for her breast: that I might ingest her pain.

It went on for years. When I was five, on holiday in Greece, I walked hand in hand with him along a beach. The simple bliss of looking out for jellyfish in the sand. But a woman called his name. I stopped and squinted up at her. She was tall, her body brown and oiled. She tipped her hips and her long hair swung when she smiled. My father dropped my hand.

‘Who’s that?’ I asked, trying to catch up with him.

‘Just someone.’

That wrinkle of questioning. Things are not as they seem.

There’s a photograph of me, small and bespectacled, a year after that trip to Greece. I’m hanging my father’s Y-fronts on the washing line. Growing up, I loved this image. He is in our everyday space, using our washing machine, and I am looking after him. But my mother has since told me she found it too painful to look at. She was afraid that handling my father’s wet clothes might have exposed me to a venereal disease she later discovered he was carrying. It’s not just damage to the heart, but the body as well.

Why did my father do it? How could he continue to cheat on my mother despite claiming to love her all the while? Nothing went wrong in their relationship. They were passionate about each other right to the end. I know that he felt wretched at times; he later admitted to trying various therapies towards the end of their marriage.

‘What if the affair had nothing to do with you?’ Perel asks her clients. In her work with couples who are dealing with the fallout of infidelity, one motivation that crops up a lot is self-discovery, a quest for a new or lost identity. In my father’s case, there was boarding school from the age of seven. From the intimate safety of his mother’s love, he was flung to a place where he had to abide by new rules along with hundreds of other little boys. No one looking out for you, no familial soil in which to grow.

In Boarding School Syndrome: The Psychological Trauma of the ‘Privileged Child’ (2015), the British psychoanalyst Joy Schaverein recognises a set of patterns of behaviour among people, such as my father, who have been sent away to prep school, including an inability to recognise emotions in one’s self and in others, to talk about feelings, and to form durable close relationships: all revolving around problems with intimacy. The boys are so young when they lose their primary attachment that they haven’t yet learned the right words to articulate their feelings. ‘There are no words to adequately express the feeling state and so a shell is formed to protect the vulnerable self from emotion that cannot be processed,’ writes Schaverein.

From the certainties of home life, my dad was thrown into an anarchy where the older boys bullied those who were younger or vulnerable. As an adult, my father confessed to his sister that he had been raped. He was certainly coerced into sex games between the boys, all of them abandoned and rudderless. He grew into puberty with very little privacy, and only limited outlets for his natural curiosity. Is this what distorted his relationship to sex? Sex as power, sex as escape? It was euphoric to win over beautiful strangers. In that moment, everything felt right.

In his essay ‘Formulations on the Two Principles of Mental Functioning’ (1911), Sigmund Freud identifies ‘the pleasure-unpleasure [Lust-Unlust] principle, or more shortly the pleasure principle’. In How to Read Freud (2005), the American writer Josh Cohen discusses the natural progression, from our libidinal drive for pleasure and survival as a newborn, to learning that eating too many sweets might make us sick, to the hope that finally the precarious rush of instant gratification will give way to postponement and its more measured satisfactions. Freud affiliates the pleasure-ego with wish and the reality-ego with what is useful and what guards us from damage. ‘This process is essentially a slow and reluctant shift of allegiance from the pleasure to the reality principle,’ writes Cohen. We learn to hold out, to moderate or resist. But my father was the eternal child with no restraint. He grew fat from eating too many cakes, smoked despite being prone to asthma, drank milk by the litre despite being intolerant. He always knew better than the doctors. When he ended up in intensive care for the third time and was told he’d die within the year if he didn’t stop drinking, I begged him, and he laughed: ‘But it’s so much fun.’

The religion encouraged sexual promiscuity and cast monogamy as merely a social construct

He finally left us, his family, soon after that photograph of me helping with the laundry was taken; I was six, my brother eight. We four stood in the yellow-lit hallway at home: my brother on the stairs, my mum at the bannister, me in the livingroom doorway, the roses of our wallpaper, soft, blowsy and sedated. My father was in the corridor, his feet perceptibly turned away from the corners of our home, our quiet intimacy.

He went to India with his new girlfriend and was blessed by his guru, Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, who put a mala round his neck and gave him a new name. The cult encouraged sexual promiscuity and cast monogamy as merely a social construct. The words adultery and infidelity were not muttered in the dusty pathways between meditation and darshan, when disciples gathered to hear their guru speak. My father had found himself an affirmative culture. He had found his people.

On his return six months later, he told my brother and I that he had been reborn. He was cleansed of the past. He introduced my mother to his girlfriend – the three of them seated on the sofa in our living room – and asked if they could both move into the family home, she in the basement, my dad back in my mother’s bed. He wanted to pirouette like a happy prince between his two women. In pure polyamory style, my father asked for my mother’s consent. She stood up and passed him his green fedora hat. ‘You must be joking,’ she said.

Although infidelity has become commonplace, it remains a leading reason for divorce. So we search for solutions, try to find new, more progressive ways to accommodate it, and a positive language that speaks of extending our love out. We remain hopelessly romantic, and yet continue to face ‘the core existential paradoxes that every couple wrestles with – security and adventure, togetherness and autonomy, stability and novelty,’ as Perel so eloquently puts it. But what of an individual’s pain?

In his musings on the Conditions of Love (2002), the philosopher John Armstrong discusses how our idea of love is at any given time dependent on the prevailing culture and its shifting values, even as ‘emotional structures like jealousy and possessiveness don’t seem to change much’. This intransigence proved inconvenient for the sexual reformers of the 1960s and ’70s but polyamorists don’t shy away from the problem or try to protect those they love with lies. In fact, they pride themselves on their conscious management of jealousy and stand by the importance of total transparency. Still, if we are to consider a relationship’s boundaries, where then do we draw the line? Apologists for adultery might say, it was only sex, she or he meant nothing. Polyamorists might do the same. Either way, intimacy is the sticking point, the moment when one night turns into two; a candle-lit dinner; holding hands on the way home.

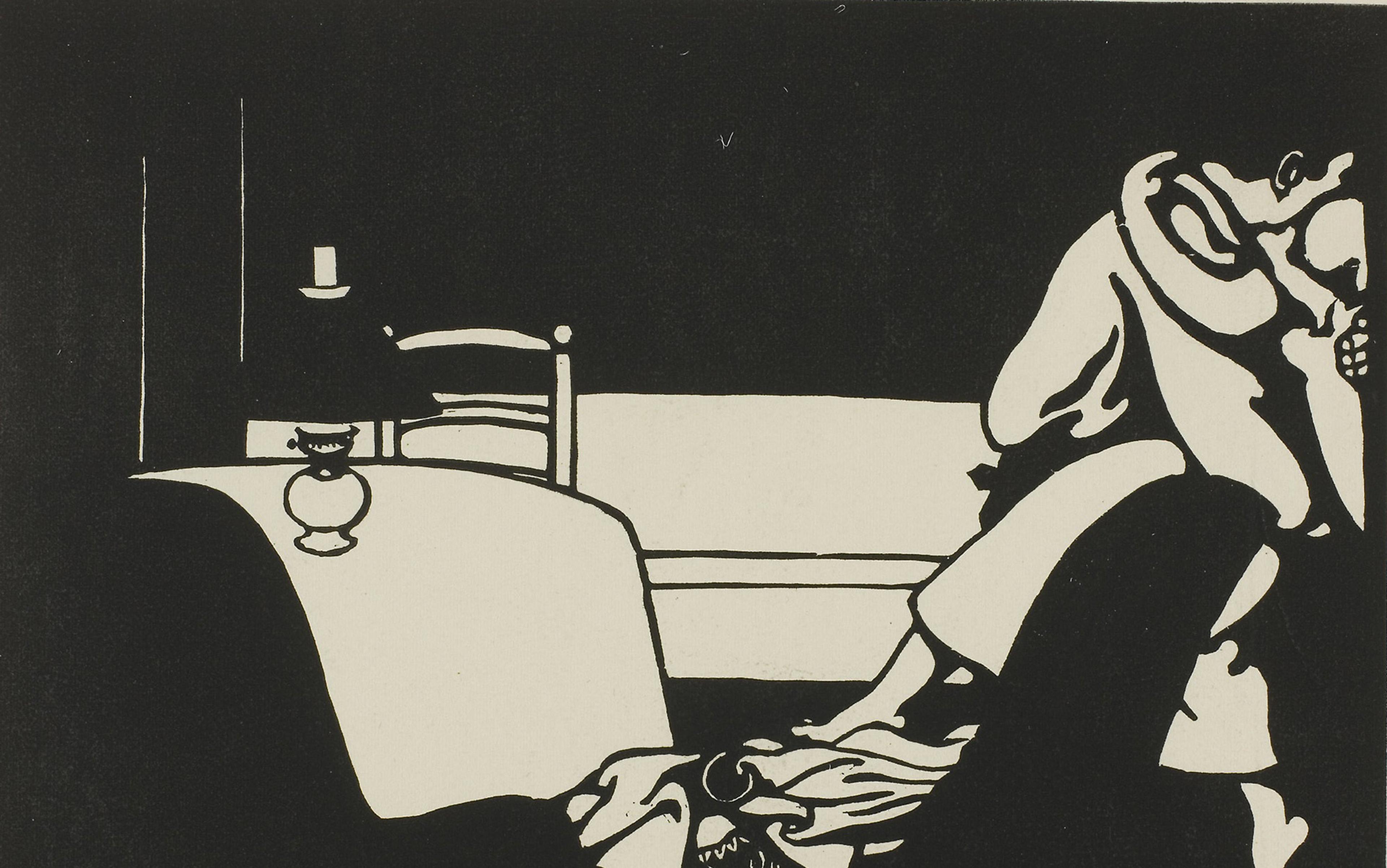

Real intimacy has less of a relationship with sex than it does with trust and the naked self. Armstrong writes of a small painting by Édouard Vuillard, which depicts a naked woman plucking a gown from the back of a chair. It’s an affectionate image that speaks of the person who witnesses the act, as well as the act itself, and the ease between them: ‘A sense of trust and comfort which are connected to tender touch. This is the sensuality of a caress, rather than of intercourse.’

We all fear losing the person we love to someone better, more beloved. It’s not something that can be talked away or prepared for. ‘If love is an act of the imagination, then intimacy is an act of fruition,’ writes Perel. ‘It waits for the high to subside, so it can patiently insert itself into the relationship.’ It takes an extraordinary person to be comfortable with their true love experiencing an equal or stronger love for another person, and it’s not easy to end a relationship that has touched you deeply, whatever your intention.

A warm hand finding you in sleep … This kind of intimacy is undone when a third party enters the frame

My father’s legacy was complex, but there was one seed, planted deep within me and tenacious in its growth. How fearful I was of infidelity. Would it happen to me? Worse: would I be unfaithful? That fear embedded itself in my heart and grew like bindweed, constricting the blood that should have run free. In my own history of love, I gave in to being ‘motionless, at hand, in expectation’ in the shadow of the ‘absent one’, as Roland Barthes so lucidly explores in A Lover’s Discourse (1977). It made me over-alert, searching for the distraction, the other lover, to emerge. Eventually, to reclaim myself again, I fled my marriage, unable to fully explain, leaving behind much hurt. My father was never able to reflect, to accept responsibility, or acknowledge his complicity in another’s pain. He never apologised to any of us. I feared, more than anything, that I would end up like him.

I understand the desire to have a totally transparent relationship. I didn’t manage it when I was preoccupied with that inflexible state that Barthes writes about, the feeling that ‘I am loved less than I love.’ But now that I know what it is to love wholeheartedly, I know there’s nothing more nourishing than giving openly and freely, or the joy that comes from total trust. Having complete communication in everything, that light and easy syncopation, spinning off in all directions and always being caught; the peace of low voices in the dark; a warm hand finding you in sleep. This kind of intimacy relies on privacy. It is undone when a third party enters the frame.

Perhaps the polyamorists, like my friend in his car, will whisper among themselves that I am fearful, but maybe it’s more that I recognise how important is the closeness of a private intimacy. Besides, what if, like pain, this commitment has a purpose? Against all that can be lost, ‘the desire to hold on to what one has, and to resent it being taken by others, is a self-protective instinct,’ says Armstrong. It feels natural to want to keep this kind of ease and comfort safe.

I am reassured by Armstrong’s premise that love is ‘recognition of what the needs of another may be’. He believes we really can ‘become more loving by developing a richer sense of what might be important to another person and by cultivating an interest in finding out what those needs are.’ This applies to those who practise consensual nonmonogamy, as well as those who acknowledge their inevitable attractions to other people but stay true to their one chosen love. Neither way is better, but both demand that you listen.

Armstrong goes on to write about the importance of imagination in love, above intensity of feeling; some might call it empathy – the ability to know how the experience of another can differ from our own. Imagination, he writes, opens up the possibility of asking: ‘How might I do things otherwise?’ With this question in our hearts, we cease putting ourselves first; instead, by giving, we make a safe space for our partners to give in return. We create that comfortable, remedial space that nourishes and protects against the stresses of life. Why deplete our lover’s energy by igniting that terrible fear of loss?

After the shelves went up, I confided in my best friend about the confession in the car, and she pulled a face, shook her head. ‘Why was he telling you this? It sounds so suspect.’ Many would have laughed it off as a bad come-on line, but I was grateful for what my pained response taught me. I learned about my own emotional landscape: that what might be considered by some as a weakness – at worst, a case of prudery; at best, a fear of letting go – is in fact my understanding of who I am, and what I need. Me, there, in the driving seat. A consensual monogamist.