This summer, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft will reach the highlight of a journey it began back in 2006. When the probe flies by Pluto at approximately 11.49am UTC on 14 July, it will snap a series of detailed, intelligence-worthy pictures of the former planet’s surface. Once the mission is complete, NASA will download New Horizons’ data, wipe its memory, and wave goodbye as the shuttered spacecraft continues on into deep space, forever.

But the craft will then take on another kind of cargo: memories of home. Engineers plan to upload the ‘One Earth’ message, the first crowd-sourced portrait of biological Earth, to the New Horizons’ hard drive some time in 2016, after all the data from the Pluto flyby have been downloaded. In the meantime, anyone with an internet connection can submit prospective images, audio, video, text and 3D renderings for the message, and a crowd will vote on what makes the final cut. It’s the most cosmic of subreddits.

Right now, the One Earth message website asks visitors for just one term describing ‘the aspect of life on Earth [they] think should be included in a message to the Universe’. I recently logged on to make my own entry, and found it a difficult task. After I finally typed out ‘connection’, the site sent me to a word cloud made of the one-word responses others had given. ‘Diversity’, ‘curiosity’, ‘hope’. ‘Poetry’, ‘Jesus’, ‘cats’.

When the US space artist Jon Lomberg, a long-term collaborator of the US astronomer Carl Sagan, first dreamed up the One Earth message project, he was motivated by one belief: missives to space should come from our whole planet, not just from powerful countries, scientists or doomsday cults. It’s a nice idea, and an audience poll works well on TV shows such as Who Wants to be a Millionaire?. But can we really count on the crowd to paint an artful portrait of itself for an alien civilisation? And should we be talking about ourselves at all?

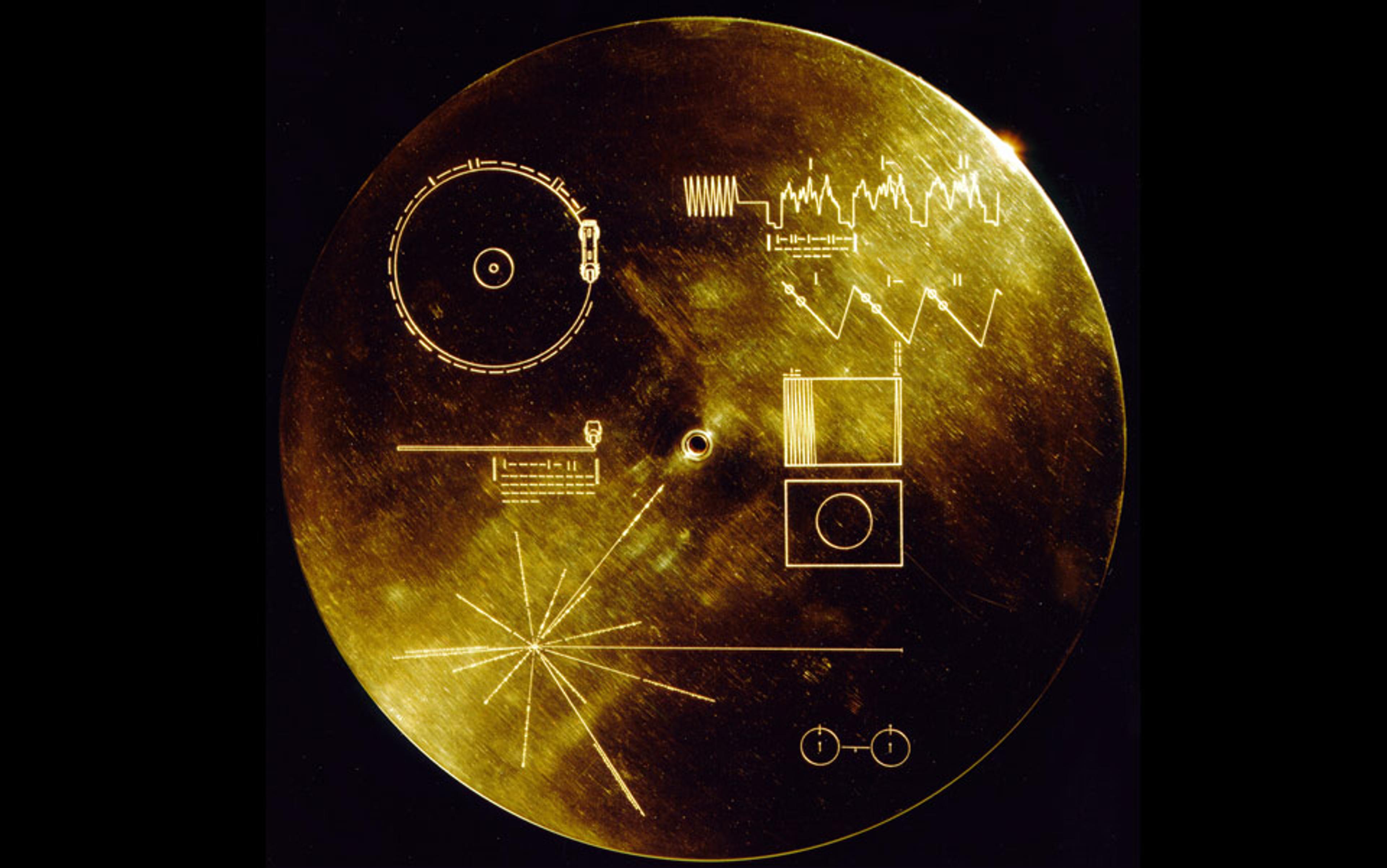

Our most famous interstellar message yet does attempt to describe life on Earth, but only six Earthlings had serious input into its contents. And two of them were in love. In 1977, the writer Ann Druyan had an EEG done for the project. She closed her eyes and thought fondly of the man with whom she’d recently fallen in love – the project’s leader, Sagan himself. When she turned the resulting brain scan into audio, it sounded like a string of pop rockets going off. She took the recording, added to it audio of her heartbeat, and engraved those sounds on a record. It would have eventually made a great wedding present for Sagan, except that this wasn’t just any record. It was a ‘Golden Record’, one of only two copies that would eventually travel to the stars aboard the twin Voyager spacecraft.

Should one of these golden records fall within the grasp of a civilisation among the stars, it will serve as an ambassador for its creators. Embedded in its grooves are 54 sound clips, 90 minutes of music, 116 images, and greetings in 55 languages. This is who people are, the message proclaims to those who might find it, be they multigenerational spaceships of biological beings, or self-replicating nanobots that understand record players. If such an extraterrestrial happened upon Voyager, it could hear a dog, a rocket, or the world’s meanest hyena (according to the library that gave Druyan the recording). They could tap their appendages to a Navajo Night Chant or one of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos. They could view a snowflake over Sequoia, a woman sampling grocery-store grapes, the Taj Mahal.

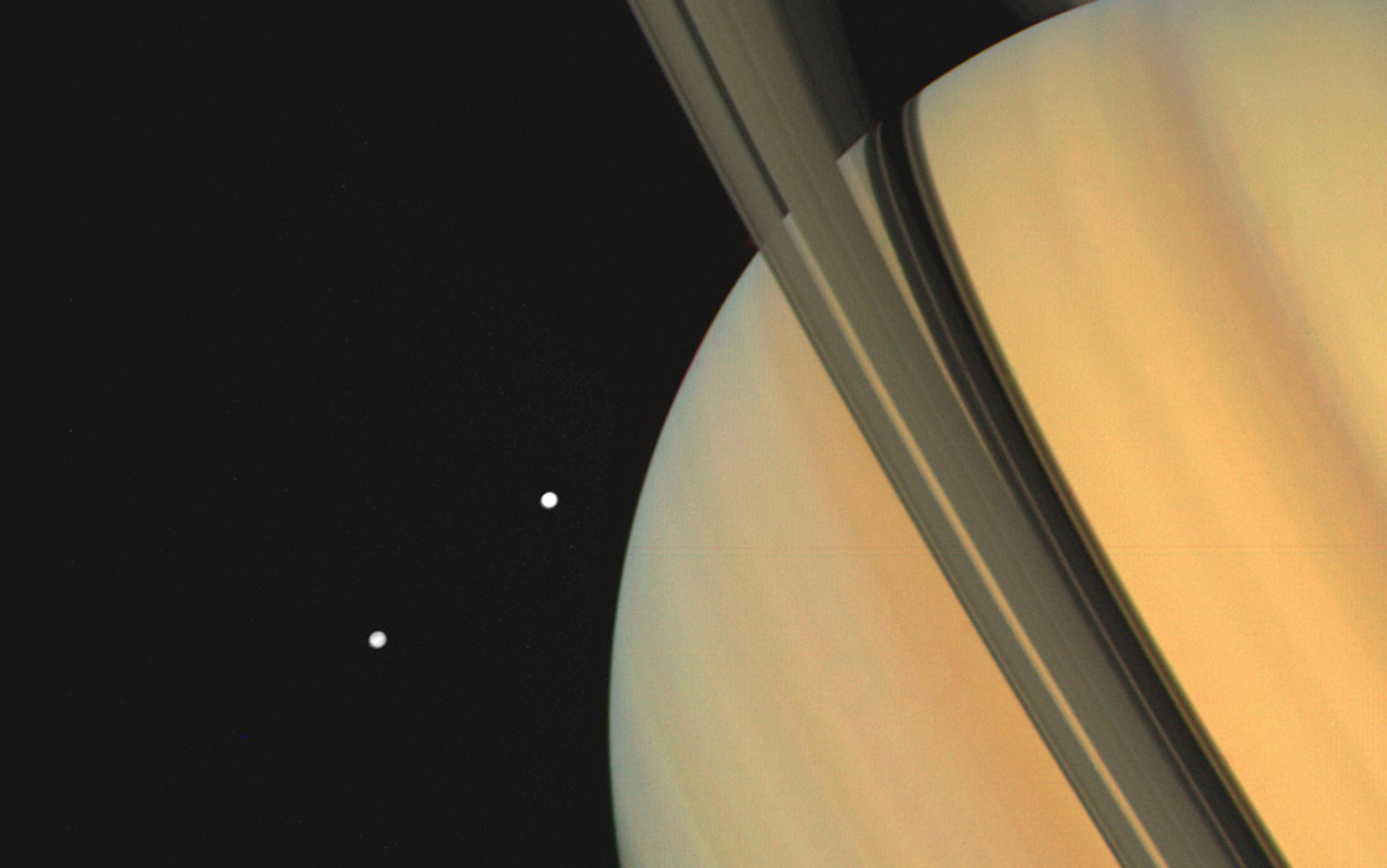

As the years passed, Voyager swept past Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. When it had travelled four billion miles from its home hangar, it turned around to take a portrait of Earth: a pale-blue dot your eye could skim right over, looking more like something you’d try to pick off a computer screen than something to spend your whole life on. If Voyager looked back toward Earth now, the planet would be too small to see. The next-closest star is still a 40,000-year trip away. Voyager is in the hinterlands, where cosmic rays from supermassive black holes wing right through its siding. It is more alone than any human, or human artefact, has ever been.

There is almost no chance that beings or bots will find the Golden Record, and Sagan and Druyan knew that. The project was a thought experiment: if extraterrestrials did find it, what would we want them to know about us? The history of Earth can’t fit on an LP. One only has so many pixels, so many ones and zeroes, so many sounds and sentences. Sagan’s team had to find the fractals in our existence: the small stuff with the same shape as the whole.

Printed on the Voyager record cover is another message, including diagrams Sagan had created five years before and engraved on the Pioneer Plaque. (The Pioneer spacecraft launched in 1972, but Voyager moved out of the solar system faster.) Sagan, together with the artist Linda Salzman Sagan, his then wife, and Frank Drake, the scientist who performed the first SETI (search for extraterrestrial intelligence) experiment, designed a graphical message to accompany Pioneer. The engravings are simple, like cave paintings for the Space Age: a man, hand raised in greeting, and a woman, both naked, stand in front of a spacecraft schematic, scaled to show human height. Below them, a smaller Pioneer flits among our planets; an arrow shows its departure from the third rock and its gravitational boost from the fifth.

To the couple’s right, lines of different lengths and orientations intersect to show Earth’s location relative to 14 pulsars. Over it all looms a graphic showing hydrogen’s ‘hyperfine transition’: the simplest atom radiates a radio wave of 1420.41 MHz. Space fairly buzzes at this frequency. The 14 pulsars’ spin periods are written out in binary, defined by their ratio relationship to 1420.41 MHz. Because pulsars slow down a little bit every second, there is only one time in history when they would spin at this speed, and only one place – Earth – from which they would appear in these particular directions. The map encompasses nearly half the galaxy, and its time stamps will remain useful for billions of years. The engravings place our species within a massive slice of space and time.

Why did the Voyager record not feature nice hyenas, or the heartbeats of people falling out of love? How could such a tiny team make decisions about a whole planet?

The messages aboard spacecraft are physical, but humans can also send electromagnetic messages into space. The first communicative emission, apart from radio and television leakage, was sent from the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico in 1974. A radar blast of one megawatt, enough to power hundreds of homes, was further amplified 10 million times by the antenna. It flew at the speed of light from the ragged-ridged mountains of Puerto Rico and passed Pluto in just four hours. Sagan and Drake had composed the message: the basics of binary arithmetic, the formulae for DNA’s nucleotides, a human figure, the solar system, and Arecibo’s dish, all pointillised into 1,679 pixels. The show was over in three minutes, and repeated just twice.

Although extraterrestrials could tell that nature alone didn’t create the pictures or the plaque, they might have trouble with the interpretation. And even if they could decipher the messages, they still won’t tell them much about us, other than that we know where pulsars reside; we like to stand next to each other; we get hydrogen’s tricks; and we live on some planet. Not exactly a nuanced portrait of a conscious people, each of whom contains multitudes.

In their supreme generality, these messages don’t leave out the !Kung hunters of the Kalahari any more than the Minnesotan farmers. It is when messages try to be inclusive that they become specific, and it is when they become specific that they exclude. Why, for example, did the Voyager record not feature nice hyenas, or the heartbeats of people falling out of love? And how could such a tiny team make decisions about a whole planet?

According to a draft statement of principles known as the Second SETI Protocol, ‘Any message from Earth directed to extraterrestrial intelligence should be sent on behalf of all Humankind. … The content of such a message should reflect a careful concern for the broad interests and wellbeing of Humankind.’ Sagan’s small team adhered to the spirit of that law, but the letter of it didn’t actually apply to them: this protocol refers only to a response if ET phones Earth. It sets no rules about unprovoked monologues, a practice known as ‘active SETI’.

Some scientists, such as Stephen Hawking, believe we shouldn’t speak to space. If extraterrestrials are Christopher Columbus, he said in 2010, we might be Native Americans. Others counter that any civilisation that detects our technology is likely much older. If they liked to blow up planets, they would have blown up their own one long ago.

Either way, the discussion is merely academic: active SETI costs money and resources we don’t have. We would have to leave a high-power transmitter on continuously – not for a few years or a few decades, but for hundreds of centuries. We can’t plan next year’s federal budgets, let alone those for the year 10,571. Our efforts to date have been largely symbolic – thought experiments rather than actual active SETI. The Arecibo broadcast was shorter than a commercial break. Pioneer and Voyager are messages in expensive bottles, cast into the biggest, emptiest ocean. Some scientists believe we should transmit only once we have the resources to do it well.

Scientists who do favour active SETI split on whether we should hide humanity’s flaws when courting extraterrestrials, just as we do on the first few dates. Sagan fell on the rosy-coloured side, with his kiss-noises and concertos. But humans do a lot of bad things. We kill each other. We rape. We melt the planet’s ice and rip holes in its ozone. We bring guns to school.

Lomberg’s One Earth message aims for a more balanced, and less censored, perspective on humanity. Using the millions (or billions) of ideas people may submit, a crowdsourcing specialist named Albert Yu-Min Lin will create consensus while maintaining diversity. Lin, a research scientist at the University of California, San Diego, will identify the ‘emergent collective reasoning’ within the message submissions: what would The Crowd think if The Crowd were a single person? But even if Lin can answer that question well, the One Earth message will be biased, because not every human being has an internet connection, or the inclination to post to oneearthmessage.org.

photos of Bush and Obama were meant to symbolise good and evil – a dichotomy surely lost on any inhabitants of Gliese 581

While the One Earth message will try to say something explicit about humans, other recent messages are more opaque. In 1999, the Russian astronomer Alexander Zaitsev composed a message that, in summary, proclaimed: humans know things about the Universe, and these are the bits we deem most fundamental. From a 70-metre radio dish in Yevpatoria, on the Black Sea coast of Crimea, Zaitsev broadcast ‘Cosmic Call 1’. It functioned as an ‘Interstellar Rosetta Stone’, beginning with simple ideas – this is an integer, that is an atom, this is not a test – and layering knowledge atop that. Instead of using language to teach science, Zaitsev used science to teach language. By the end, the self-decoding message describes Earth’s atmospheric chemistry, Mount Everest’s height, and Homo sapiens’ sensory sensitivities. He sent this New Age stone tablet toward five Sun-like stars, encouraging recipients to respond.

However, for Cosmic Call 2 in 2003, Zaitsev had merged with a Texas-based project called Team Encounter, a fee-based ‘people’s space programme’ (that went out of business a year later). Cosmic Call 2 began with the Rosetta Stone but then moved on to less universal topics: 282 national flags, pictures of Ukrainian schoolkids, a recording of David Bowie’s Starman, and a resolution declaring the second Tuesday in February to be Extraterrestrial Culture Day, at least in New Mexico.

In 2005, a Florida-based private enterprise called the Deep Space Communications Network collected more than 138,000 messages to aliens left on the Craigslist website. These were free – but for the low, low price of $299, customers can now record a five-minute voice message, too. The now defunct website TalktoAliens.com was also in on this idea, letting people record a greeting at a rate of $3.99 per minute. In 2008, RDF Digital, now part of the French TV company Zodiak Media, sent ‘A Message from Earth’ from Yevpatoria, after collecting 501 messages through the social networking site Bebo. Comprising text, drawings and photos, they contained none of the context an extraterrestrial civilisation would need. Side-by-side photos of George W Bush and Barack Obama, for example, were meant to symbolise good and evil – a dichotomy surely lost on any inhabitants of Gliese 581, a system with potentially habitable planets, where the message went. NASA’s ‘Hello from Earth’ – 25,880 random texts from random Earthlings, and also meant for Gliese 581 – followed in 2009. By 2029, when these messages are due to arrive, if anyone in Gliese 581 is paying attention, they will certainly be confused.

As if all that were not incomprehensible enough, in 2008 the US food manufacturer Frito-Lay funded a competition for the first ever extraterrestrial commercial: an ad for Doritos that would be beamed into space! The book publishing industry, loath to be left behind, publicised Paul Davies’ The Eerie Silence: Are We Alone in the Universe? (2010) with another interstellar competition. Penguin sent 1,000 readers’ messages to space, and the 50 best submissions won a hardcover copy of the book. The winning entries were about as serious as the contest: ‘We don’t bite, do you?’ and ‘Please send pictures of your celebrities.’

Given the degradation that comes with democratisation, should we let the madding crowd near the broadcasting equipment? What kind of a god-awful global self-portrait will all these people (yes, you, and you) create? The One Earth message might be full of LOLcats, Katy Perry videos, and Twitter-length snark. Imagine a being that grew up on the starlit surface of a distant planet. If such a being stood before you, would you say: ‘I’ll show you our celebrity pics if you show me yours’?

The One Earth message helps us imagine that such a being does stand before us. Like the Voyager Golden Record and the Pioneer Plaque, and unlike the 20th century’s other messages, the One Earth message will be a physical artefact. Extraterrestrials almost certainly will never find it: so small, not all that shiny, muddling through the middlest of nowheres. Cosmic rays will erode its digital bits, a rot we won’t be able to fix after the power dies in 10,000 years.

But the corporeality that dooms the One Earth message is also what makes it feel real. A broadcast, like yelling for help in the Mojave Desert, feels like a shout into the void. It’s invisible, and it flees from us faster than anything else in the Universe. But because space artefacts have mass, we feel their gravity. When we can picture our messages leaving the Solar System, we can almost picture our alien audience. We think about what it might means to be them, and to be human. We realise we are a few strands of DNA teetering on the surface of a planet in a G-dwarf system, wracked by existential crises and self-awareness, constantly striving for more than we have, and trying to scrape longer-than-lifetime grooves into Earth.

Our audience might not have eyes or language. How can we talk to them about existential crises when we can’t even imagine their sensory lives? After all, what is it like to be a bat? The differences between us and them will be much larger than those between some of us and others of us: when you think about an alien that has three suns and no ears, a miner in Eritrea doesn’t seem so different from a middle-manager in Idaho. While one wears an ill-fitting suit and one a safety vest, they both have arms. Dopamine makes them both happy. They both dream during REM sleep. By conceiving of ourselves as more ‘Earthling’ than ‘Eritrean’, we can better identify what it is that makes us so. That was the spirit of the Golden Record, and it is the spirit of the One Earth message.

From Druyan’s heartbeat to Bowie’s songs to whatever boards New Horizons, it has always been, and always will be, about us

In 2012, the US artist Trevor Paglen created the most recent space artefact with that same spirit. Paglen designed an image-based space artefact that will last billions of years. This capsule, called The Last Pictures, lives above us in a ‘graveyard orbit’ that never spirals back to Earth. Paglen micro-etched 100 photographs (chosen with input from artists, scientists, anthropologists and philosophers) on to an ultra-archival disc, created in collaboration with materials scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The disc’s future discoverers will find a dust storm, a waterspout, petroglyphs, cherry blossoms, medical tools, Earthrise, Agent-Orange victims, and covert government ops sites.

Despite his inclusive efforts, Paglen rails against the idea that The Last Pictures represents humanity – or that representing humanity is even possible. He calls it ‘one person’s impression of what humanity was like at this one moment’. And besides, he says, the pictures will be meaningless after a billion years. The people in gas masks might as well be the orphans seeing the ocean for the first time.

The Last Pictures made Paglen think about which images form his impression of humanity, and those choices were ultimately personal. But with a crowd-sourced artefact, every human being with an internet connection can share in Paglen’s experience, stepping back to examine and construct his or her individual impression of humanity in this one moment. Because even though space and time are full of places we’ll never go, things we’ll never see, and beings we’ll never meet, our experience of here and now is worth remembering.

That inner grappling is the real point of interstellar messaging. It has never been about ‘them’. From Druyan’s heartbeat to Bowie’s songs to whatever boards New Horizons, it has always been, and always will be, about us. Sagan and Druyan never expected extraterrestrials to find their contracting aortas and firing axons and understand ‘what it means to be human’. They wanted to say to themselves – and to the world – ‘This is what it means to be us.’ Sometimes, they didn’t even mean ‘us’ in the general sense: after all, it’s not your love that’s immortalised beyond the heliosphere. It’s not Sagan’s, either. The experience is uniquely and impenetrably Druyan’s.

When we can do actual active SETI, we shouldn’t smugly type out ‘connection’, curate a many-megapixel photo album, or muse about the music that tugs on our brainstems. When we have a real shot at contacting extraterrestrials, we should send only blank broadcasts. Ping, blip, a cosmic dial tone, a blinking cursor on an empty line. After all, the most important information about humans is not that we like Bach, understand quantum mechanics (kind of), or live by oceans. Our most noteworthy quality is that we exist. We are here. You are not alone: that’s all we need to say, and all we would need to hear.