William Blake’s childhood vision on Peckham Rye is well known. Sauntering along, he looks up and, according to an early biographer, ‘sees a tree filled with angels, bright angelic wings bespangling every bough like stars’. On another occasion, he ran indoors declaring he had seen the prophet Ezekiel under a tree. His wife, Catherine, later reported that Blake first saw God at the age of four. I love that ‘first’.

The Bible’s vivid prophetic and visceral apocalyptic imagery stirred him as well. It ‘overawed his imagination’ so that ‘he saw it materialising around him,’ Peter Ackroyd reports in his biography Blake (1995). When as an adult he became an engraver, artist and poet, Blake was driven to enable others to apprehend such sights. In one of his epic poems, ‘Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion’ (1804-20), he declared:

… I rest not from my great task!

To open the Eternal Worlds, to open the immortal Eyes

Of man …

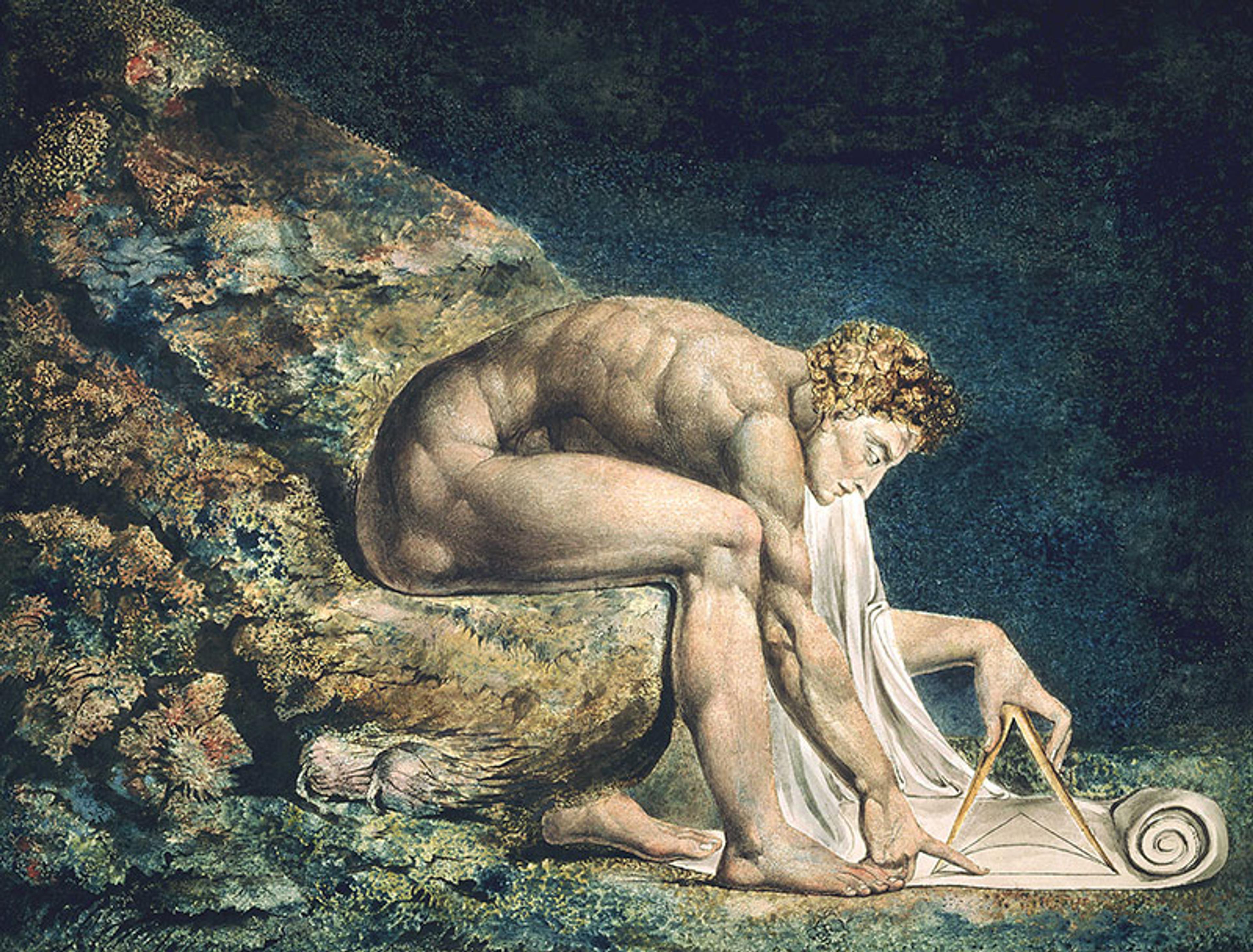

At the time, there were few with the eyes to see and ears to hear him. The industrial age was booming, manifesting the insights of the scientific revolution. It was a tangibly, visibly changing society, fostering an almost irresistible focus on the physical aspects of reality. The narrowing of outlook is captured in one of Blake’s best-known images, entitled ‘Newton’ (1795-1805). It depicts the natural philosopher on the seabed, leaning over a scroll, compass in hand. He draws a circle. It’s an imaginative act. Only, it’s imagination rapt in the material world alone, devoted to studying what’s measurable. For Blake, Isaac Newton represents a mentality trapped within epicycles of thought. While claiming to study reality, it isolates itself from reality, and so induces, as he wrote in a letter to his patron Thomas Butts, ‘Single vision and Newton’s sleep’.

Newton (1795–c.1805) by William Blake. Courtesy the Tate Gallery, London.

Many of Blake’s contemporaries regarded him as eccentric or mad. But a different mood prevails today. Busts are as evident as booms. Civilisation itself can feel as if it teeters on the brink. Blake’s critique of ‘dark Satanic Mills’ now appears prophetic; his advocacy of the need for ‘Mental Fight’ to liberate the imagination sounds like a calling. When, on a damp Sunday in 2018, a substantial slab of handsomely engraved Portland stone was unveiled to mark his burial place at Bunhill Fields in London, hundreds gathered, having heard about the occasion by word of mouth. They were addressed by Bruce Dickinson, the lead singer of the heavy metal band Iron Maiden, who described Blake as one of the greatest living English poets. And he meant ‘living’. Blake never really dies, the rock star insisted.

This sense of his immortality arises with a recognition of the conviction upon which Blake bet his life: the human imagination is not only capable of entertaining fantasy. When coupled to creative skill and penetrating thought, it reveals the truths of existence and life. It converts everyday incidents into rich perceptions that might amount to a revolution in experience. It underpinned Blake’s vocation as a visionary and a thinker, as Northrop Frye stressed in his study of the man, Fearful Symmetry (1947). And it promised the gift of what Blake called ‘fourfold vision’, a taste of which can be gained by considering what it allowed him to perceive when observing the sunrise. ‘When the Sun rises, do you not see a round disk of fire somewhat like a Guinea?’ he has an interlocutor ask him in an imagined exchange. ‘O no, no! I see an innumerable company of the heavenly host crying, “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord God Almighty!”,’ he replies.

The appearance of divine intelligences as dawn breaks – Frye called it ‘the Hallelujah-Chorus perception of the sun’ – will look like an ecstatic product of a fanciful mind to those expecting the Sun to look like a golden disk in the sky. But Blake could see more because he had realised that he saw the sunrise (and everything else) not with his eyes, but through them. Blake’s promise, therefore, is that the imagination, carefully embraced, frees you not to see more in the Sun, as if he were projecting jubilant angels onto its blazing orb, but to see more with and through the Sun. He understands that it is not the physical eye that enables what we see, but the mind’s eye: the retina, optic nerve and brain are the servants, not masters, of perception. We are all in exactly the same predicament; it’s just that the individual who detects only the guinea-sun has opted to see the guinea-sun alone, perhaps believing that they’ve side-stepped the part that imagination plays in what they perceive to arrive at an imagination-independent image of our stellar neighbour.

This is to close ourselves up, to paraphrase Blake’s remark from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790-93). It is to see all things through the narrow chinks of our caverns, because we take as gospel truth the doctrine of scientific materialism that nature is purely physical. That starts to unravel once we realise that our conscious impressions can’t be divided from objective viewing, as if the former were a deluded epiphenomenon. Rather, the issue is how accurate and inclusive any take on the world is – a take that can diversify and expand as the imagination deepens and grows. ‘A fool sees not the same tree that a wise man sees,’ Blake wrote, and then he tempts us further: ‘If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite.’ This is no psychedelic hope or dreamy aspiration. Blake is a philosopher and artist. He understands how perception works, theoretically and practically. And there are ways to open ourselves up and escape the cavern.

In his poetry, Blake describes four states of mind that exhibit distinctive attitudes towards the imagination and, therefore, experience the world in very different ways. By recognising which state a person or society finds themselves in at any one time, it’s possible to become more capable of entertaining, embracing and entering others. He gave these states names: Ulro, Generation, Beulah, and Eden or Eternity. They offer litmus tests if you want to follow Blake: if you seek fourfold vision, it’s essential to have a feel for how dramatically they differ.

Ulro is the state of single vision. ‘In Ulro, that which can’t be expressed quantitatively does not exist,’ writes the Blake scholar Susanne Sklar. Wisdom is sought in logic and numbers, and debate is met with the cry to gather more evidence. It’s the state of mind experienced by the subterranean Newton, whose devotion to measurement curtails his awareness. The imagination is absorbed by this data capture. It works like an obsessive tourist pointing and clicking, pointing and clicking with a camera, while experiencing little or nothing new. The Sun is guinea-form in Ulro, an average star, in an average galaxy, lost in the vastness of the Universe.

It’s a mentality that has proven highly desirable. During a pandemic, it motivates what it takes to flatten the curve or increase the amount of testing and, more generally, it organises life around metrics such as economic growth and GDP. Only, it’s never quite clear what these seeming goods are for, with the upshot that people and societies feel stuck in Ulro’s ‘dull round’, to use Blake’s phrase. Many people live haunted by the fear that something has gone wrong and life lacks meaning. Others become so invested in this lifeworld that they refuse to consider that they might lack sight.

This is because, from Blake’s point of view, the human imagination has swung into reverse. Unconsciously, it is working hard to discount what he called the ‘minute particulars’ that are the stuff of life, preferring instead an existence described in generalisations and statistics. Ulro also hasn’t much to say about crucial experiences such as suffering and death, beyond saying that they must be the meaningless byproducts of natural processes. That itself compounds the suffering, producing ‘a weary Life, in brooding cares and anxious labours, that prove but chaff’. Although, as Blake trusted, there’s always an opportunity in despair: he argued that this single vision ultimately serves to highlight what it’s missing. So, as the crisis deepens, the confusions of Ulro’s state of mind can become clearer, which can prompt a shift of consciousness, to the state of mind Blake called Generation.

Societies fill the environment with dark satanic mills. Supermarkets stock up on varieties of toothpaste

Generation is ruled by a spirit of reproduction. Its twofold vision grasps more of the nature of life. It understands biological cycles and productive seasons and, in the modern world, has fostered great advances in manufacturing and farming. In Blake’s poetry, the character of Los is often in this state. He swings his tongs and hammer, tools that can forge and fashion, not merely measure like Newton’s compass. He labours to build the city of Golgonooza, a hoped-for utopia that’s really a restive city on Earth. The eternal prophet Los desires more life although, in the state of Generation, this is sought through categories such as longevity and health that are imaginatively limited. Doubts about the meaning of life, therefore, persist.

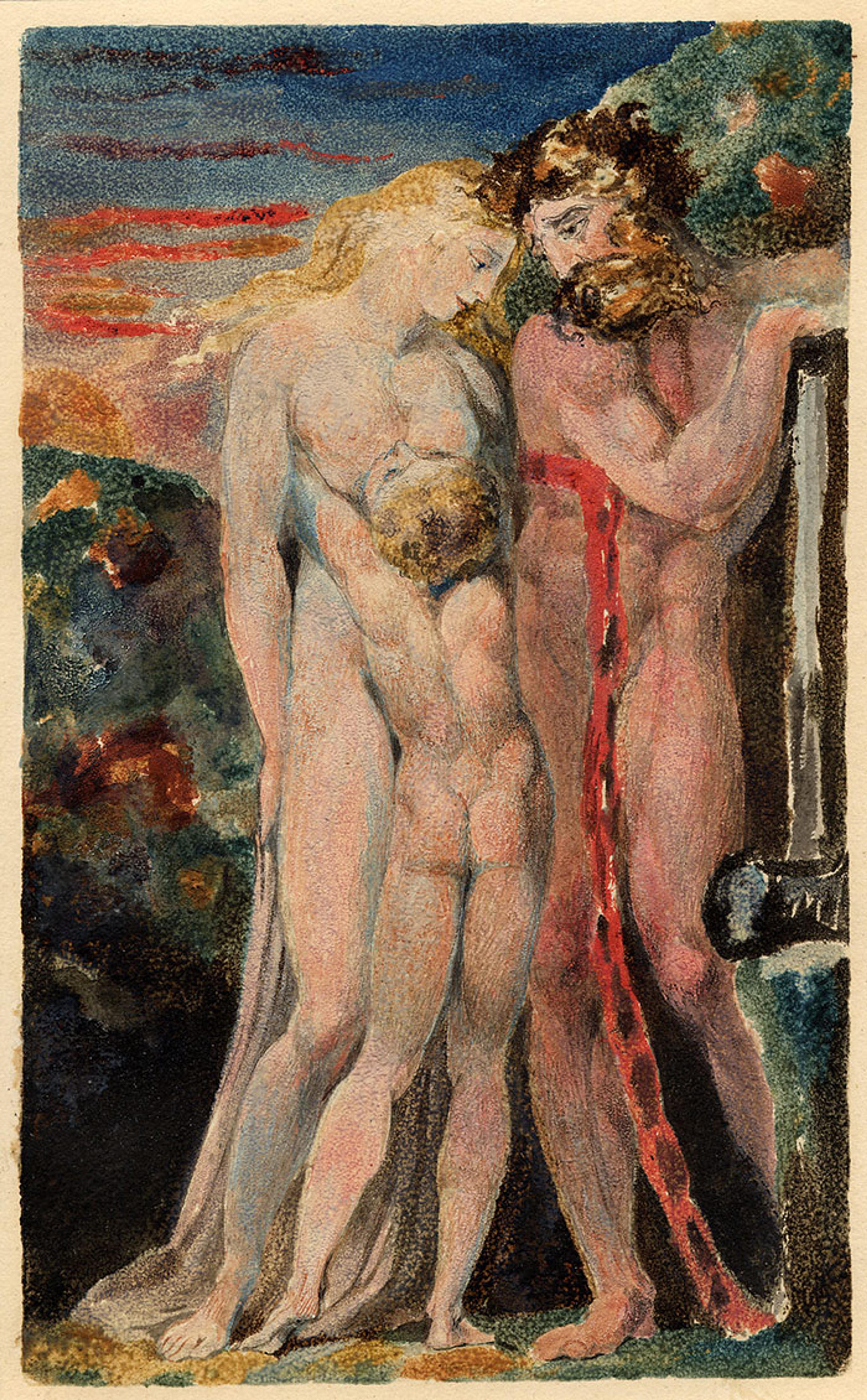

From The First Book of Urizen; Enitharmon, Los and their child Orc, Los is depicted with hammer, anvil and his red “Chain of Jealousy”. Courtesy the Trustees of the British Museum.

When it comes to the Sun, people in Generation will remark that they are made of stardust, acknowledging that, in celestial nuclear furnaces, stars like the Sun forged the building blocks of life, such as carbon. They will discuss the many ways in which an average star, like our Sun, is about right for the genesis of biological life. Even wonder at that fact. It’s a modest, mental upgrade to the appreciation of our blazing companion.

So, Generation is more expansive than Ulro. It gives Ulro’s reason a framework and purpose, though still struggles to see life’s higher dimensions. The nagging sense that life should offer more therefore means there’s a constant risk of Generation slipping into pursuing reproduction for reproduction’s sake; a slide into mere replication. When this happens, societies fill the environment with dark satanic mills. Supermarkets stock up on endless varieties of breakfast cereal and toothpaste. The Earth becomes smothered by a noosphere of supply chains. Consumption rules.

Things can grow darker. Aware that resources are limited, people start to talk about the survival of the fittest, as if scarcity were an irresistible law. They become convinced that life is best modelled as a series of prisoner’s dilemmas and zero-sum games. The Ulro mentality creeps back in, and people worry as replication blooms like a summer algae strangling the sea. Perversely, they might seek to ease the anxiety by demanding more material goods, in habits akin to what Sigmund Freud in 1920 called the repetition compulsion. As things run out of control, life is felt to be complexifying at exponential rates and panics set in. It’s not really. It always was complex. Rather, people have lost their bearings for lack of imagination. But, as before, the crisis becomes an opportunity to perceive more. Threefold vision can break through.

Tweets of hope are drowned by threads of hate. It’s a dangerous time

This is the perception of the state that Blake called Beulah. It introduces an awareness of and desire for felt relationships. Sensitivity and care, sympathy and happiness and, above all, love and affection come to the fore, offering the narrower states of mind windows on to new dimensions of life: Beulah can warm Ulro’s chilly reason and orientate Generation’s directionless reproduction. Rich seams of meaning and value, aspiration and recreation are uncovered, to the extent that people in Beulah intuitively know what it means when life is said to have interiority and soul. What was ‘I-It’ becomes ‘I-Thou’, to recall Martin Buber. Delighted by the experience, people will talk to blackbirds, sing to the stars, hug trees. Poets will pen lines to the now blissful Sun. They will couple it romantically to the Moon, and praise its warmth and light for falling equally on all. Some might detect intimations of divine blessing within that pattern.

Beulah is alert to ethics and morality because it appreciates the minute particulars of life. It tries to identify principles that can defend what it holds dear, particularly when relationships break down, as inevitably they do. Justice and fairness become significant and, in this mood, a philosopher such as Immanuel Kant will muse: ‘Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the more often and steadily we reflect upon them: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.’

However, Beulah’s threefold vision has a dark side, too. It can be blighted by what Blake called ‘Selfhood’, when love becomes possessive and wants to control relationships. People cite rules rather than offering forgiveness, resort to the courts rather than reconciliation and, when culture wars break out, ethics is weaponised in shaming and scapegoating. Selfhood blasts Beulah’s landscape of affection, leaving what Blake called ‘the Wastes of Moral Law’. It divides, ostracising people and fostering wariness by demanding that everyone embrace a puritanical and punitive version of what was Beulah’s commodious worldview. Tweets of hope are drowned by threads of hate.

It’s a dangerous time. Yet if Beulah can learn from its compulsions, and loosen the grip of Selfhood, it can discover wider horizons and a participation in life that is freer than previously conceived. A fourth lifeworld can start to be imaginatively anticipated: Eden/Eternity.

Blake’s fourfold vision finally achieves take-off in Eternity: the multivalent perception that opens on to infinite life. Space becomes fractal, time fluid. It happens as imagination is trusted as a living power of creativity with which we can cooperate. Eternity shares in nothing less than divine life, when imagination’s ingenuity isn’t only spectacular and fun, but generative and lasting. As Blake’s contemporary Samuel Taylor Coleridge put it, fancy rearranges what it already knows, more or less arbitrarily, often just for effect; whereas imagination synthesises, makes, bridges the subjective and objective, and perceives the interior vitality of the world as well as its interconnecting exteriors.

Eternity includes and makes sense of the best of the other states: the discernment of Ulro, the expansiveness of Generation, and the feeling of Beulah, which is why artists and visionaries trust it. When Vincent van Gogh painted starry nights, the enchanted cosmos became visible once again. When Albert Einstein envisaged travelling on a light beam, which was the imaginative exercise that fostered the special theory of relativity, physics uncovered new worlds. The geniuses of science and the arts work hand-in-hand in Eternity, illuminating each other. Blake celebrates such moments in lines from ‘Jerusalem’:

At the clangor of the Arrows of Intellect

The innumerable Chariots of the Almighty appeard in Heaven

And Bacon & Newton & Locke, & Milton & Shakespear & Chaucer

Ethics gains higher aims, as a result. It is no longer about the identification and defence of moral principles, but morphs into what Blake called ‘Wars of Love’, the effort mutually to transcend old patterns of behaviour and embody the qualities of personhood called virtues. It happens by ‘laying/Open the hidden Heart in Wars of mutual Benevolence’ in operations of ‘ferocious forgiveness’, to use Sklar’s phrase: ferocious because unstintingly honest; forgiving because merciful towards whatever is exposed. It judges to understand, not condemn; to liberate, not subjugate. It welcomes mistakes as opportunities for the kind of learning that transforms the soul as well as the mind.

Eternity’s secret weapon is a new type of friendship, which Blake captures in a line from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: ‘Opposition is true Friendship’. Moreover, the opposing friend opposes themselves as well. They embrace what Blake called ‘Self-Annihilation’: the mental fight with oneself, which isn’t about dissolving the ego but routing the desire to possess life and control others. In ‘Jerusalem’, Blake describes Albion embarking on Wars of Love by voluntarily launching himself into Los’s fiery furnaces.

From the Song of Los. Courtesy the Trustees of the British Museum.

It is crucial to seeing the more promised in Eternity since it renders the individual transparent to reality. I think Virginia Woolf was on to a similar realisation in A Room of One’s Own (1929), when she ponders the genius of William Shakespeare’s mind, how it is ‘resonant and porous’, ‘creative, incandescent and undivided’. That could happen because ‘All desire to protest, to preach, to proclaim an injury, to pay off a score, to make the world the witness of some hardship or grievance was fired out of him and consumed.’

The cosmos is alive and pluriform. Seeking out its parallel universes can become part of life

The Wars of Love also transform the perception of death. In Ulro, death is bewildering; in Generation, a travesty; in Beulah, a tragedy; but in Eternity, it’s the gateway to fuller life. ‘Every kindness to another is a little Death,’ writes Blake, not just because kindness might cost, but because such sacrificial acts can be experienced by the giver as moments in which to realise that they never possessed life to start with. Rather, they live because life pours itself into us. The nature of being alive is revealed as a ‘comingling’ of mutual self-sacrifice. The giving and receiving precipitates ‘Fountains of Living Waters’ and, for Blake, the Christian, reveals the meaning of Jesus’s death and ours. In Eternity, the everyday deaths through which we pass on life, as well as the seemingly final death of passing over, reveal that there’s a source of life. It is a timeless love, which includes and transcends death.

A changed meaning of freedom reveals itself now too, although its claims might baffle or offend the states of mind that Eternity supersedes. In Ulro, freedom is assumed to grow with an increased ability to grasp the world; in Generation, it’s equated with more choice; in Beulah, with expression and respect. But in Eternity, freedom is found in service and in submission – a meaning that is also embedded in the Sanskrit origins of ‘yoga’: to join or yoke. This is because when relinquishing is perceived as the wellspring of life’s everlasting waters, people strive to embody the dynamic by aligning with it. Blake sang of this bliss in the quatrain that can take a lifetime to realise:

He who binds to himself a joy

Does the winged life destroy

He who kisses the joy as it flies

Lives in eternity’s sunrise.

There is a further type of relinquishing required to live in eternity’s sunrise. In Blake’s mythology, it takes us back to Los’s efforts to build the restive city, Golgonooza. It turns out that, upon perceiving Eternity, Los actually gives up the struggle. He realises that Eternity’s heaven is not a place on Earth and never could be. As writers on utopias since Plato have discerned, trying to manifest such hopes in the wrong realm is a terrible mistake. It consumes the material Earth by driving an insatiable growth. It compounds the suffering of nature and humanity. The trick when building Golgonooza is to let it go as it fails, though something lasting and invaluable is gained in all the striving: the ability to appreciate and receive Eternity. ‘I must Create a System or be enslav’d by another Man’s,’ cries Los during his struggles, not because he is individualistic but because he desires the divine and realises that creative imagination is the crucial preparation for it.

Eternity likewise casts a different light on contemporary concerns about ecological devastation. It shows that the material world alone is too small for us. Our capacity for transcendence means that we are creatures of infinity. We can notice ‘Heaven in a Wild Flower’ and ‘Eternity in an hour’, though the perception should also be a warning; as Blake stressed: ‘More! More! is the cry of a mistaken soul, less than All cannot satisfy Man.’

His vision for ecology is, therefore, not one of managed exploitation (Ulro), managed consumption (Generation), or even managed cooperation (Beulah), but instead one aimed at radically extending awareness of the ecologies of which we’re a part. It means embracing not just the environments and organisms studied by the natural sciences but the divine intelligences appreciated by the visionaries, plus a panoply of gods, spirits and daemons that our ancestors took as read.

Blake saw angels and ghosts and the Hallelujah sunrise. To cleanse the doors of perception and regain serious contact with these dimensions of reality matters not only because it might counter deadly demands for all of the material world, but also because we are made to enjoy the spiritual dimension. Cutting it out is cutting off a part of ourselves.

For most us, much of the time, my guess is that, at best, Eternity is glimpsed on occasion. Such moments are signs. Long term, we cannot live in even a well-functioning Beulah, let alone mitigate the excesses of Generation’s and Ulro’s closed systems, trapped in themselves. But Blake’s descriptions, the energy of his verse, and his imagination, can help us expand our sight in the light of the signs we receive, just as he made much of having seen angels on Peckham Rye. The cosmos is alive and pluriform. Seeking out its parallel universes can become part of life.

Fostering that hope somehow feels crucial right now. It’s possible to pay attention to the states of minds in which we live, and move more fluidly between them. Blake offers a training and roadmaps. It’s work, as is any genuine shift of consciousness. But human beings can cooperate with the imagination and awaken as new acuity arises. ‘Eternity is in love with the productions of time,’ Blake remarked. That’s because Eternity knows it’s our destiny.