In 1962, the Colombian priest and sociology professor Camilo Torres Restrepo travelled to the north of the country to investigate a dispute between powerful landlords and subsistence farmers. Spending days wielding machetes with Black cane cutters and nights drinking rum with them, he learned of their 40-year struggle against their wretched conditions at the mercy of a local landowner and senator. Competing for land with his grazing cattle, they had been ‘whipped, fired upon, beaten back to the riverbanks and their humble dwellings burned to the ground.’

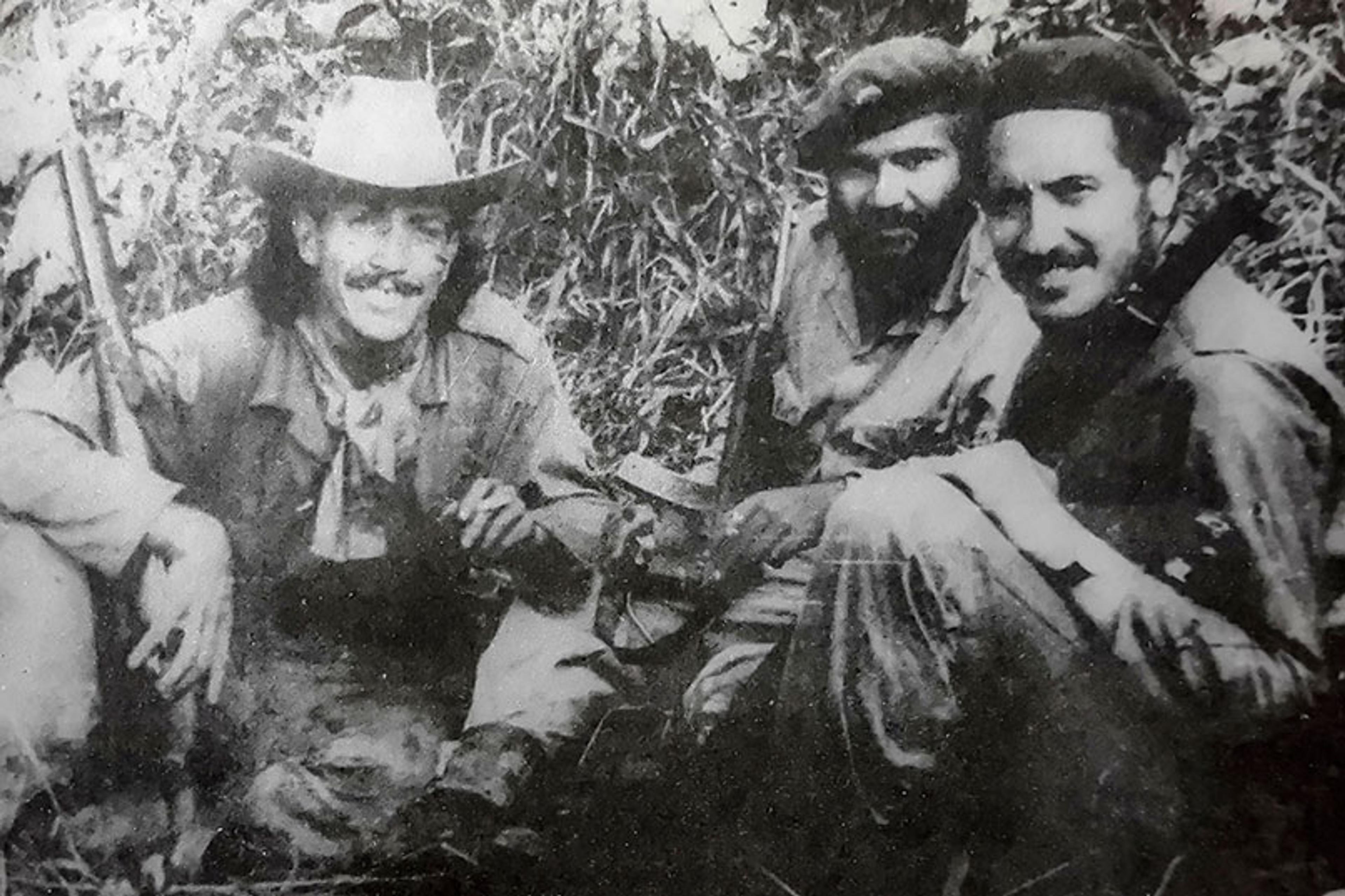

Camilo Torres Restrepo with Fabio Vázquez and Victor Medina Morón, in the journal OCLAE, no 2, 1967. Courtesy Histoire Engagée

Described by his biographer Walter J Broderick as the ‘Che Guevara of the Christian world’, Torres began working across spiritual lines with communist, student and trade union groups as he dedicated himself to improving the conditions of the downtrodden. ‘More concerned with the action itself than with the theory behind it,’ Torres was relieved of his orders in 1965, after which he took up arms with the National Liberation Army, a Marxist-Leninist guerilla group. ‘The common people,’ he wrote to a friend, are ‘the only hope for change.’

Insisting on being given no special treatment and fighting as a regular soldier, the following year Torres wrote a powerful homily to the nation on his decision to take up arms. ‘For many years the poor of our country have waited to hear the call to arms which would launch them on the final stage of their long battle against the oligarchy,’ he wrote. Years of corrupt elections and failed coups meant that ‘the moment for battle has arrived.’ Adamant that he had ‘not betrayed’ the people, Torres added: ‘I have not ceased to insist that we give ourselves to this cause unto death.’

It was a prophetic letter. Torres died shortly after writing it, killed in his first battle, by the first bullet fired at him. Long viewed by the military as a threat, Torres was taken, his body secretly buried and its location kept a state secret for years so he could not become celebrated as a martyr. One man’s heroism is another’s terrorism, and Torres’s story was often cited as proof that Left-wing social justice movements, supported by a new breed of clergymen, wore a crown of daisy-chains to conceal a violent and sinister mission.

Even for the many who disapproved of Torres’s decision to trade his vestments for khakis, the mood for change within the Catholic Church was already taking powerful shape.

At the Second Vatican Council (Vatican II) between 1962 and 1965, the Church agreed a series of reforms to meet the modern world’s challenges. Even Pope John XXIII had, a month before the Council’s opening, noted that in ‘underdeveloped countries, the Church is, and wants to be, the Church of all and especially the Church of the poor.’ The decrees that were eventually issued by Vatican II sought to make the Church more democratic and modern, but they did not go far enough for many in its progressive wing.

Lay people wanted change, too. Groups that became known as Christian Base Communities were both a response to Vatican II’s call for ordinary believers to take a more active role in the Church, and a sheer necessity. Largley growing from the most desperate regions of the Brazilian Amazon, they began as Bible study and prayer groups formed in poor and remote parts of the continent that were starved of pastoral care. In 1970, some 40 per cent of Brazilian priests were foreigners. By the 1980s, there was only one priest for every 9,367 people, and the ratio continued climbing in the 1990s.

There simply weren’t enough priests to effectively look after their flock, another strain amid growing disconnection from the Church in Europe. As the sociologist Cecília Loreto Mariz puts it in Coping with Poverty (1994), the largest Catholic nation in the world was ‘still a mission outpost’. Demographic needs were one thing, but a cultural shift was underway too. At a time when global economic forces were accelerating ideas of self-reliance, spiritual nourishment was not immune – something that would become telling two decades later, when a more vibrant gospel of personal betterment would sweep all before it.

Liberationists believed that they were bringing the Church back to the teachings of Jesus

Real and necessary as they were, liberation theologists emphasised Base Communities beyond their influence. Impoverished and often illiterate people coming together to practise their faith by any means necessary was a romantic idea, blown out of proportion. Initial studies seriously overestimated the scale of Base Communities by as much as a factor of 10. In fact, no more than 4 per cent of Brazilians – in 1970, that meant about 3.8 million people out of 96 million – are believed to have ever belonged to one. What they did, however, was give voice to ordinary people, and empower the progressive wing of the Church, which was calling for a more democratic approach to faith and wider society.

The 1968 General Conference of the Bishops of Latin America and the Caribbean (CELAM) held in Medellin, Colombia saw the nascent movement that would become known as liberation theology begin to take its first steps. The bishops issued a document that understood three meanings of poverty: an evil God does not want; spiritual poverty, or a readiness to do God’s will; and, finally, solidarity with the poor. The conference also consciously introduced the term ‘liberation’ to the cause for spiritually led societal change.

Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI, in 1965. Public domain

With this new direction came the first rumblings of criticism. It was 1968 after all, and the febrile geopolitical climate saw great possibility, but a strong pushback against change. Until that year, a young German theologian named Joseph Ratzinger – the future Pope Benedict XVI – had been politically liberal, but he began developing an increasingly conservative outlook that divorced faith from secular politics. In promising to forefront the poor, and go beyond charity to seek broad and lasting solutions to their poverty, liberationists believed that they were bringing the Church back to the teachings of Jesus. Ratzinger, and many of his European colleagues, saw things very differently.

Five years after Torres’s battlefield death, his former schoolmate and friend from the Catholic University of Louvain, the Peruvian theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez, put the ideas of the fledgling Latin American movement into print with his book A Theology of Liberation (1971). He understood the movement as a ‘commitment to abolish injustice and to build a new society’, where freedom from exploitation, and ‘the possibility of a more human and dignified life’ was built on four principles. First and foremost is the prioritisation known as the ‘preferential option for the poor’, which he later said encompassed 90 per cent of the movement. He also believed that an unequal society was a sin, and valued the importance of unchurched lay gatherings of the faithful, such as Base Communities, and the commitment to taking a ‘see, judge, act’ approach to injustice.

God makes his sympathies clear from Cain and Abel, Gutiérrez argued, the parable mirroring ‘God’s predilection for the weak and abused of human history’. Jesus makes the will for material justice even more explicit, best surmised in the Bible verse: ‘I have come that they may have life, and that they may have it more abundantly.’ This wasn’t a God of death and afterlife, but of the here and now. On a deeply Christian continent that had (and still has) some of the greatest wealth and resource disparity on Earth, abundance was out of reach for most. ‘In liberation theology, faith and life are inseparable,’ Gutiérrez later wrote in a reflection on his original work. ‘These concrete, real-life movements are what give this theology its distinctive character.’ The poor deserve to be elevated, Gutiérrez argued, ‘not because they are morally or religiously better than others,’ but as it is expressed in the gospel of Matthew, that ‘the last will be first, and the first last.’

Spiritual life could not be divorced from the material world, and it was an existential issue for the Church. From the colonial era through to the brutal far-Right and military dictatorships that came to dominate Latin America in the 20th century, the Catholic Church was replicating the hierarchies that harmed God’s people. For too long, God’s emissaries in Rome had served earthly power. Too often, the almighty dollar had been a servant of poverty, and a master of the poor.

It wasn’t only the Vatican that was on the offensive against liberation theology

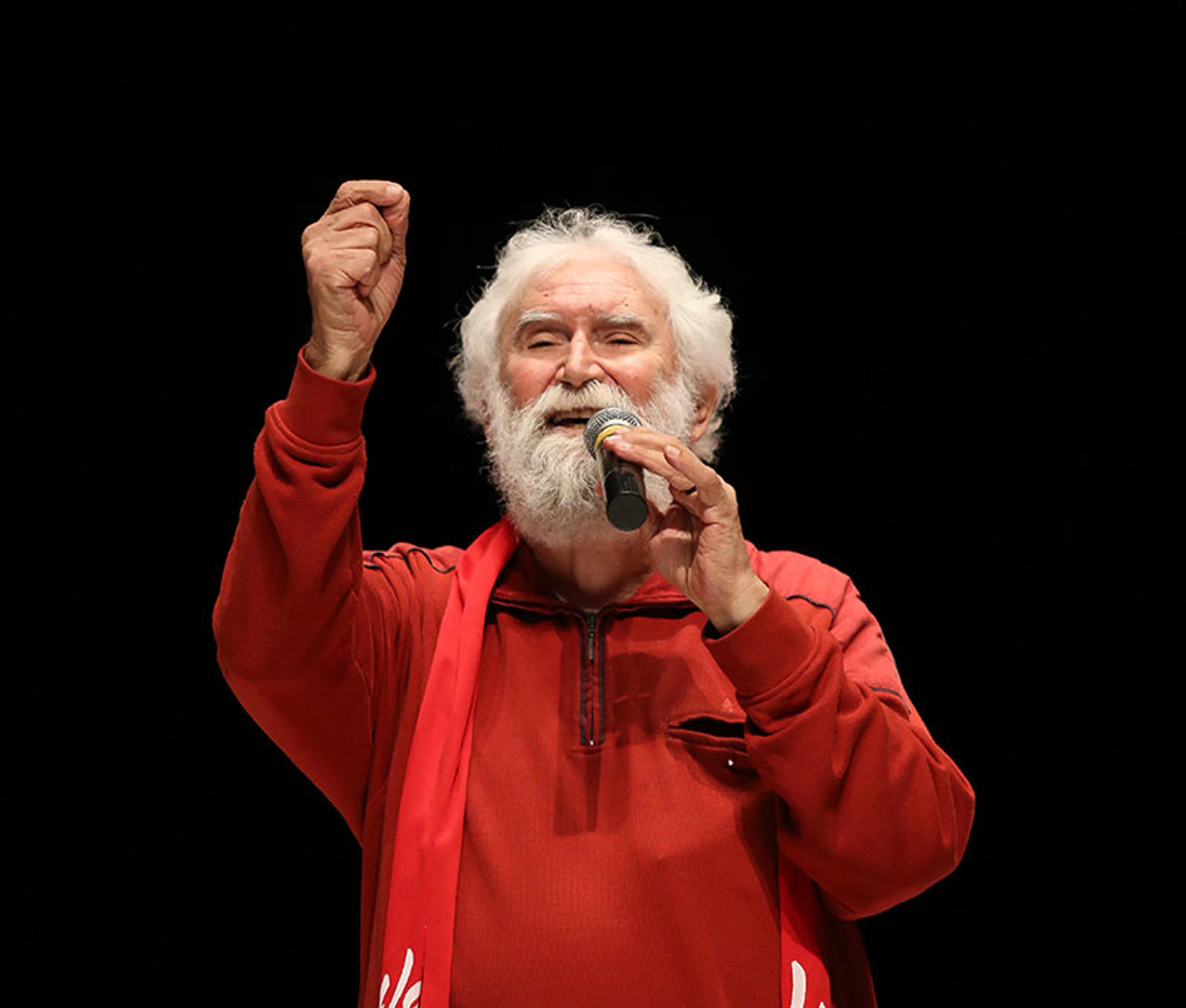

One year after Gutiérrez’s book, the Brazilian philosopher-priest Leonardo Boff published Jesus Christ Liberator. Unabashedly shaped by Marx and intent on ‘decentring’ the Church to welcome disparate cultures, Boff was a champion of Base Communities, and one of the Vatican’s most trenchant internal critics. Influenced by the Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung, who introduced the idea of ‘structural violence’ to the secular world, Boff expanded on the concept of ‘structural sin’, the idea that sin can be a social or economic action, and not simply an individual one.

The Brazilian theologian Leonardo Boff, pictured in 2018. Courtesy Manuale d’Avila/Flickr

Around this time, repressive military dictatorships in the cone of South America were beginning to transition to civilian governments, and anti-communist fervour shifted its centre of gravity to the Central American nations. The religious studies professor R Andrew Chesnut says it wasn’t only the Vatican that was on the offensive against liberation theology: ‘They faced fierce national repression in countries such as Brazil, Argentina, El Salvador and Guatemala, where brutal military dictatorships saw them as communists.’ The ensuing dirty wars in Central America, with plenty of aid and comfort from the United States government and mercenaries, killed around 350,000 people in Guatemala, Nicaragua and El Salvador, and displaced millions more.

Most proponents of liberation theology explicitly condemned violence, while pointing out the differences between ‘structural sin’ that they saw as the institutionalised violence of inequality, and violent action against injustice. However, Ratzinger and other orthodox Catholics continued to mount objections to the movement, gathering evidence from Torres’s deeds and Boff’s words to declare the movement heretical.

Their attentions turned inward, they failed to see a far greater threat to their power and authority in another movement bubbling up from below, albeit from a very different Christian tradition. It was one that would go on to claim far more of the continent’s souls and move them even further away from the edicts of European cardinals.

Pentecostalism, a US-born branch of evangelical Protestantism centred on the Holy Spirit, had been gaining ground in the region throughout the 1970s. Two decades later, Pope John Paul II denounced Pentecostals as ‘ravenous wolves’ who were stealing the Catholic flock. Their attraction was prosperity theology, or the gospel of health and wealth, where true believers who give generously to their Church will receive back riches of mind, body, spirit and wallet many times over.

Emerging from the same social and economic conditions as Base Communities and liberation theology, the divergent paths of the two religious movements over the next four decades tell a much broader story about the secular world.

If there was a family that liberation theology was born to serve, it was Edir Macedo’s. Born in the small country town of Rio das Flores in Brazil, to a Catholic mother who endured 33 pregnancies, including 16 miscarriages and 10 premature births, he was one of seven surviving children. The fourth child and second oldest son, Macedo’s genetically deformed hands made him the target of bullying, both at school and at home.

Like many Brazilians from the regions, the family migrated to the outskirts of a major city, in their case, Rio de Janeiro. When he was a teenager, Macedo’s elder sister Elcy developed chronic asthmatic bronchitis that was failed by the medical treatment available. The family sought help at a spiritist centre, a kind of folk homeopathy that brought together strands of African slave religions, Christianity and pseudoscience.

Having no luck, Elcy heard a radio broadcast from the Canadian Pentecostal preacher and faith healer Robert McAlister. Visiting his New Life Church in downtown Rio, her asthma disappeared and, within a year, the entire family became devotees. Macedo converted at 19, but when 11 years later, his daughter was born with a cleft palate, his devastation led him to a ‘revolt’ that he said was ‘not against God, but against hell.’ Macedo quit his job and took to street preaching in crime-soaked favelas, before forming his Universal Church of the Kingdom of God in 1977.

Long before McAlister had touched the Macedos, in 1911, the renegade Swedish Baptist Daniel Berg brought the Assembly of God to Brazil after witnessing the Pentecostal fire when he worked as a foundryman in the US. Evangelical missionaries came and went across the continent with little success, before Americans from the Foursquare Gospel arrived in the 1950s. Both were Pentecostal movements, a branch of the evangelical faith that emphasises the role of the Holy Spirit and a direct experience and personal interaction with God, and all of the blessings and miracles that come with it. While Charles Fox Parham could be credited with birthing the movement in Kansas in 1901, it was his adopted spiritual son, William J Seymour, a Louisianan son of freed slaves, who gave it life in 1906, with the Azusa Street Revival in what is now downtown Los Angeles.

Fearing the slippery slope towards communism, business leaders and Christian leaders found common cause

Unlike traditional Christian denominations, what became known as Pentecostalism cut away intermediaries and allowed believers a direct relationship not only with God, but with all of his promises. Specifically, the nine miracles of the Holy Spirit, including speaking in tongues, prophecy and faith healing. Though it faced stiff opposition from the Catholic Church and even some of the few Protestant Churches in the region, as early as 1916, the Pentecostal movement had penetrated eight countries in Latin America. The Assemblies of God grew by an average of 23 per cent per year between 1934 and 1964. Brazil alone boasted more than a million members of Pentecostal congregations by the early 1960s. The Pentecostal movement expanded to become a worldwide phenomenon in just over a century. Pentecostals and Charismatics numbered just 58 million in 1970; by 2020, that number was 635 million. What brought so many into the tent was the prosperity gospel.

Pentecostalism really got going in North America after the Second World War, coinciding with the US elevation to global superpower. This brought forward a flood of optimism; yet, for many leaders of both faith and industry, it was a time for vigilance. Business leaders were scarred by the economic safety net implemented by Franklin D Roosevelt’s New Deal. Christian leaders were terrified of the godless ‘reds’ sweeping Europe. In fearing the slippery slope towards communism, these interests found common cause. While they were busy merging the languages of business and Bible, the Pentecostals, often looked down on by their evangelical counterparts, were stoking new revivalist fires across the country. Out of the spirit of this patriotic postwar nation arose a new vision of Christianity.

Prosperity theology, often known as the gospel of health and wealth, emerged with the help of syndicated radio and cassette-tape technology. Kate Bowler, the author of Blessed: A History of the American Prosperity Gospel (2013), says: ‘Inverting the well-worn American mantra that things must be seen to be believed, their gospel rewards those who believe in order to see.’

Pentecostals embraced the resurgent idea of ‘mind power’, and added the miracles of healing and prosperity to what Bowler calls an ‘electrified view of faith’. If this way of ‘doing Jesus’ had just been plugged in, then the publication of Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking (1952) turned up the volume to max. The New York-based preacher, who was born Methodist then born-again Reformed, invented a simple formula – picturise, prayerise, and actualise – that self-help gurus have been peddling ever since, a precursor to the ‘mind, body, spirit’ trend in both Christian and secular thought in the 1960s and ’70s. Peale’s message was a huge hit with the faithful, spreading rapidly from coast to coast. His Marble Collegiate Church on Fifth Avenue was standing room only. One family was firmly planted in the front row with their young son: his name was Donald J Trump.

Bowler says the prosperity gospel is the result of the ‘American gospel of pragmatism, individualism and upward mobility’, where churchgoers ‘learned to use their everyday experiences as spiritual weights and measures’. Critics of the prosperity gospel rarely acknowledge that ‘when many people say “prosperity”, they mean survival,’ Bowler says. For many ordinary believers, it is the same quest for abundance that the liberation theologists expressed.

While the US was on the up, Brazil was in the midst of its own Great Migration. Between the 1930s and the ’80s, millions began moving to the more central cities from the poor north-east, displaced by ranchers who could make use of poor farming land for grazing. Slavery had nominally ended in 1888, but indentured servitude continued in some areas of the north-east into the 1990s. The cities offered rural northerners economic opportunities beyond tilling the fields for those who could only generously be described as their bosses. In 1960, São Paulo had a population of 4 million; today, the wider urban area has grown to five times that.

Pentecostalism gained traction among poor migrants from the countryside who moved to the outskirts of large cities looking for work, like the Macedos. That was followed by a reverse migration of sorts, as new converts took the religion back home to the impoverished rural communities where Base Communities had flourished. Early research on Pentecostal converts suggested that they were the poorest of the poor.

As gifts from the US to Latin America go, the prosperity gospel is up there with the military coup. The best and worst of this muscular US ethos trickled down the Atlantic, both by culture and by military might. From the 1950s, many middle-class Brazilians believed that US culture spoke to a glittering sense of progress that they ought to emulate.

Macedo understood what he aspired to be, but also where he came from. Universal churches began offering services between 5 am and midnight throughout the week, understanding that most working people struggled to attend in standard hours. More than that, the spiritual nourishment of going to a service before or after a long day of work was fortifying. As Pentecostal churches began to cram into the storefronts of the nation’s favelas, they quickly became familiar institutions that were markedly different from the distant Sunday cathedrals. Their pastors spoke in the vernacular of the streets, were often mixed-race and had little-to-no theological education; their sermons used everyday problems to understand the Bible.

The golden toilet seats of prosperity gospel entrepreneurs are not a deterrent but rather a sign of God’s gifts

After the end of military dictatorship and economic growth, by the 1980s and early ’90s, Brazil had the 11th largest economy in the world, but its social indicators were similar to poor African countries. As Mariz writes: ‘many already have rich spiritual lives, so they’re after something that can help them understand and cope with the changing world around them.’

The golden toilet seats and private jets of prosperity gospel entrepreneurs are not a deterrent but rather, for most true believers, a sign of God’s gifts. Derided as gullible, they would describe themselves as motivated. If Macedo rose up from below, why can’t I? Pentecostal preachers have always had a knack of turning established ideas on their head. Catholic priests came to resemble loathed bureaucrats; Pentecostal preachers looked a lot more like inspiring entrepreneurs. The average person seeking wealth is usually looking for it in terms of a promotion at work, helping to keep creditors at bay, or starting their own small business. During services, it’s not unusual to see worshippers hold aloft Bibles topped with debt notices or money.

As Macedo’s following grew, he used funds from his flock to buy a television network, Record, in 1989. Today, he is a self-made billionaire who has received everything he owns from believers – including his only son, Moysés, given to Macedo in the street as a baby by its birth mother. To this day, prosperity gospel’s trickle-up economics continue. Smaller churches practise what they preach and become satellites for established megachurches by ‘sowing’ a percentage of their church income in order to receive the blessings of those who are materially more successful, therefore spiritually more devout.

The threat to the Catholic Church was far greater than the one that liberation theology posed, and the Vatican was compelled to compromise. The Charismatic Catholic Renewal (CCR) arrived in Latin America in the early 1970s, around the same time as liberation theology was emerging and Pentecostalism was gaining steam. ‘Liberationists historically saw Catholic Charismatics as alienated bourgeois citizens with Right-wing political inclinations,’ Chesnut says. Largely imported from the US, ‘it found traction that liberation theology did not.’ In the CCR, believers could have their gospel of health and wealth, but keep their saints and retain connections to Europe and the Catholic hierarchy.

‘Among Protestants and Charismatic Catholics, the prosperity gospel has become hegemonic,’ Chesnut says. ‘It’s come from Latin America, but is now the driver of faith in Africa and other parts of the Global South too.’ Brazil has recently crossed the line where there are now more Pentecostals and Charismatics than traditional Catholics, undoing 500 years in 40, and it’s largely thanks to the prosperity gospel. For a long time, people assumed that it was a regional outlier. Just as they spoke Portuguese while everyone else spoke Spanish, they were embracing the Church of the Holy Spirit rather than Mary and the Saints. If recent trends are an indicator, the rest of Latin America may be on the cusp of this theological revolution, too.

The 1976 earthquake that left one-sixth of Guatemala homeless saw Californian missionaries arrive with the Pentecostal faith. Their missionary zeal and a bloody civil war, in part presided over by the world’s first Pentecostal leader, Efraín Ríos Montt, saw around 60 per cent of the country converted – making it proportionately the most Pentecostal nation in the world. Pope John Paul II’s ravenous wolves are howling at the doors of El Salvador, Chile and Argentina, but even in the staunch Catholic holdout of Mexico, the state of Chiapas recently tipped to majority Pentecostal. By no coincidence, it is also the country’s poorest and most Indigenous state.

In 1984, only 16 years after the bishops in Medellin had first outlined a social justice under the banner of liberation, Cardinal Ratzinger was ready to issue last rites on the movement. The idea was simply too radical, and one that was ‘incompatible’ with established Church doctrine. To many inside and outside of the Holy See, it was nothing short of heresy – and needed to be punished accordingly.

Ratzinger summoned Boff to the Vatican to account for his accusations against Church authoritarianism, before Boff was given a silencing order, which the theologian Harvey Cox suggested was due to the ‘grass-roots religious energy’ Boff represented. Ratzinger continued to defend his stance, even after Boff left the Church altogether, suggesting that his censure had served as a warning to other like-minded theologians.

In August 1984, the Cardinal issued an extraordinary decree, Libertatis Nuntius, an instruction responding to the Latin American movement known as liberation theology, which called for a radical reorientation of the Church towards social and economic justice. Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI, might have been known as ‘God’s Rottweiler’, but when it came to teachings that questioned established hierarchies and beliefs, he was Pope John Paul II’s sottocapo. Together, the two fervent anti-communists executed a well-planned hit on a movement that orthodox clergy saw as Marxism in holy cloth.

Ratzinger warned that deviating from Papal authority risked ‘provoking, besides spiritual disaster, new miseries and new types of slavery.’ He believed that liberation theology subverted the meaning of truth and violence. A doctrine ‘incompatible with the Christian version of humanity’, it had, he said, an ‘ideological core borrowed from Marxism.’ To his mind, Marxists believe only in class and class struggle, and see society as inherently violent. That leaves no room for Christian ethics, such as good and evil. Unshackled from morality, Marxists are then compelled to participate in the struggle and to reverse the nature of domination by establishing their own.

Some argued that the ‘preference’ for the poor ran against the universal Christian message

Such was the hammer blow of Ratzinger’s decree that an early obituary of the movement in The New York Times showed that opposition to liberation theology was every bit as political as the movement itself. Written by Michael Novak, resident scholar in religion, philosophy and public policy at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, DC, it claimed that the movement’s ‘Marxist thread’ was ‘just one of its many flaws. It is a robe of many vibrant colours.’

Novak objected to theologians who took liberation theology ‘seriously as a theology, rather than regarding it as merely a political vision.’ There was no reason to conflate the two movements, as he saw them: ‘the birth of social conscience in the Church’ and the secular dependency theory, the idea that the development and enrichment of some countries happens due to the exploitation of others. One of his more compelling arguments was that some corners of the traditionally anti-capitalist Latin American Church viewed their societies as capitalist. Most countries in the region, he argued, housed ‘precapitalist’ economies that were ‘disproportionately state-directed’.

Novak’s critique bears the liver spots of Ronald Reagan-era foreign and economic policy, believing that liberation theology’s ‘main enemy’ was the US, a ‘hostility’ that he said ‘embodies a kind of liberation theology’ in itself. In rejecting Western ideas of ‘distinctions between religion and politics, church and state, theological principles and partisan practice’, liberationists who wouldn’t take communion with Augusto Pinochet were postponing the Christian virtue of loving their enemy.

Spiritually, the critiques ran stronger. Some said the overtly political nature of liberation theology meant that it reduced salvation to action taken by humans, not God. By prioritising social action, it also undermined the principle of spreading the good news and saving individuals soul by soul. Some argued that the ‘preference’ for the poor ran against the universal Christian message. A Church that came from below, such as was found in Base Communities, ran against the hierarchical nature of the Church.

Perhaps most powerfully, liberation theology simply never strongly resonated with the people for whom it was supposed to serve. ‘In many ways, it was an overly intellectual construct,’ Chesnut says, a charge that the movement has never been able to overcome. At the same time, many of the churches ministered by liberation theology priests were departing from traditions, and ‘clearing their churches of the saints’, Chesnut says. For so many Latin American Catholics, the saints and the Virgin Mary were a significant part of their faith. In the end, ‘these liberationist parish churches came to resemble Protestant churches.’

The refined hands that crafted liberation theology were in stark contrast to the calloused palms that would ecstatically whoop and clap

Whether liberation theology would have been able to succeed without the Vatican’s intervention continues to be debated. It didn’t matter. Ratzinger appointing conservative bishops across Latin America helped to salt the earth and ensure the movement would be largely confined to small corners of academia. Fixated on combatting internal enemies, they failed to see what was happening out of their stained-glass windows. By 1992, the year when Boff left the priesthood before receiving a second silencing order, a Protestant church opened every two days in Rio de Janeiro. Soon, Macedo’s Universal Church of the Kingdom of God was opening two new churches each week. Reflecting on the seismic time, Ratzinger would blame the ‘widespread exodus’ of the faithful to Pentecostalism on ‘politicisation of the faith’ by liberation theology.

There were many reasons why people began converting, but doing it in reaction to the politics of a movement that struggled to move much beyond intellectual circles isn’t one of them. The refined hands that crafted liberation theology in darkened rooms were in stark contrast to the calloused palms that would ecstatically whoop and clap and promise the power of healing could be channelled through them. Too busy trying to defeat the insurgency from bookish Latin American priests, they failed to see the insurgency happening outside the cathedral walls.

Even then, it’s been argued that the Vatican managed to destroy the men, but not the ideas. As the US journalist John L Allen Jr points out, the ‘four elements of the liberation theology movement – the preferential option for the poor, structural sin, Base Communities and the “see, judge, act” method – have largely withstood the test of time.’ Chesnut argues that the current Brazilian president Lula and his Workers’ Party are the heirs to the Base Community movement that many of its figures had grown up in: ‘Lula and many others essentially migrated from the Church as they became politicised.’ Ironically, Pope Francis, once an opponent of liberation theology, may also be one of its few remaining proponents, even if he doesn’t expressly use those terms. In 2022, Ratzinger’s successor said that, sociologically, ‘I am a communist, and so too is Jesus.’ He is also rumoured to have personally consulted Boff on some of his recent encyclicals.

But the stark reality is that liberation theology, which wanted to build the kingdom of heaven on Latin American soil, has retreated further into academia, far from the mobilising force on the ground that it once promised. Whether it would have thrived without Ratzinger’s determination to stamp it out is a live question, but it’s one that may be best answered by the continuing rise of Pentecostalism and the prosperity gospel in the intervening 40 years. ‘When you’re poor, you often have acute and immediate afflictions, and you’re looking for immediate solutions to them,’ Chesnut says. ‘The problem with liberation theology was that it promised long-term structural solutions.’

The priests of liberation ‘opted for the poor, but the poor themselves opted for Pentecostalism,’ says Chesnut. But as the Spirit-led faith and its prosperity doctrine continues its unrelenting march through Latin America, it may just be that the very orthodox Catholic hierarchy in Europe that instigated the intellectual civil war in its own ranks is paying the greatest price.