Last year, a collaborative group of anonymous Tumblr scribes rewrote William Shakespeare’s most iconic play, Romeo and Juliet, in a familiar animal language:

What light. So breaks. Such east. Very sun. Wow, Juliet.

What Romeo. Such why. Very rose. Still rose…

The language of the translated Romeo and Juliet is likely to be familiar to anyone who’s spent time on the internet. ‘Wow’ and ‘so very’ are elements of doge, a fanciful meme that describes the world through the eyes of an adorable Shiba Inu, a Japanese breed of canine. Doge has a very particular structure: ungrammatical and incomplete, it mimics baby talk. But it’s also, as the US linguist Gretchen McCulloch has observed, the kind of language we imagine our pet would have if it could speak; a language that’s as simplified as it is silly. And though doge is downright ridiculous, an internet meme meant to generate shares and laughs, it is one of the most recent manifestations of an enduring human fantasy: the talking animal.

The fantasy of talking animals predates doge, and its internet ancestor LOLcats, by thousands of years. Long before the baby talk of a Shiba Inu was rendered in Comic Sans across the web, Plato imagined the legend of the Golden Age under Saturn as a nearly idyllic time when ‘man counts among his chief advantages… the communication he had with beasts. Inquiring of them and learning from them.’ Plato’s idea appeals to the ancient dream of Arcadia; the tempting lore that there was a perfectly peaceful time when man, in his natural state, could converse with beasts. It’s a dream that seems to transcend religion – in its biblical manifestation, Arcadia is the Garden of Eden and, while in perfect harmony with all of God’s creation, Adam and Eve could converse with a snake. But the time of talking to animals has long disappeared. It remains only a figment or fantasy and, depending on your position, was interrupted either by culture or by sin.

Whether or not animals have the ability to speak, or even have inner lives to speak of, is another question. We know that animals can communicate with one another – their hierarchies and intricate rituals have been quantified and observed. But humans are disposed to anthropomorphism. We tend to project our thoughts onto other species. We can’t help but infer consciousness when a cat purrs at a welcome touch or a dog betrays a guilty look when scolded for stealing food. But does your cat really have an inner life?

In his Apology for Raymond Sebond (1580), Michel de Montaigne ascribed animals’ silence to man’s own wilful arrogance. The French essayist argued that animals could speak, that they were in possession of rich consciousness, but that man wouldn’t condescend to listen. ‘It is through the vanity of the same imagination that [man] equates himself with God,’ Montaigne wrote, ‘that he attributes divine attributes for himself, picks himself out and separates himself from the crowd of other creatures.’ Montaigne asked: ‘When I play with my cat, who knows if she is making more of a pastime of me than I of her?’

Montaigne’s question is as playful as his cat. Apology is not meant to answer the age-old question, but rather to provoke; to tap into an unending inquiry about the reasoning of animals. Perhaps, Montaigne implies, we simply misunderstand the foreign language of animals, and the ignorance is not theirs, but ours.

Montaigne’s position was a radical one – the idea the animals could actually speak to humans was decidedly anti-anthropocentric – and when he looked around for like-minded thinkers, he found himself one solitary essayist. But if Montaigne was a 16th century loner, then he could appeal to the Classics. Apology is littered with references to Pliny and a particular appeal to Plato’s account of the Golden Age under Saturn. But even there, Montaigne had little to work with. Aristotle had argued that animals lacked logos (meaning, literally, ‘word’ but also ‘reason’) and, therefore, had no sense of the philosophical world inhabited and animated by humans. And a few decades after Montaigne, the French philosopher René Descartes delivered the final blow, arguing that the uniqueness of man stems from his ownership of reason, which animals are incapable of possessing, and which grants him dominion over them.

Descartes articulated his view of the animal as mere automaton in a letter to the English philosopher Henry More in 1647:

It has never yet been observed that any animal has arrived at such a degree of perfection as to make use of a true language; that is to say, as to be able to indicate to us by the voice or by other signs, anything which could be referred to thought alone, rather than to a movement of a mere nature; now all men, the most stupid and the most foolish, those even who are deprived of the organs of speech, make use of signs, whereas the brutes never do anything of the kind; which may be taken for the true distinction between man and brute.

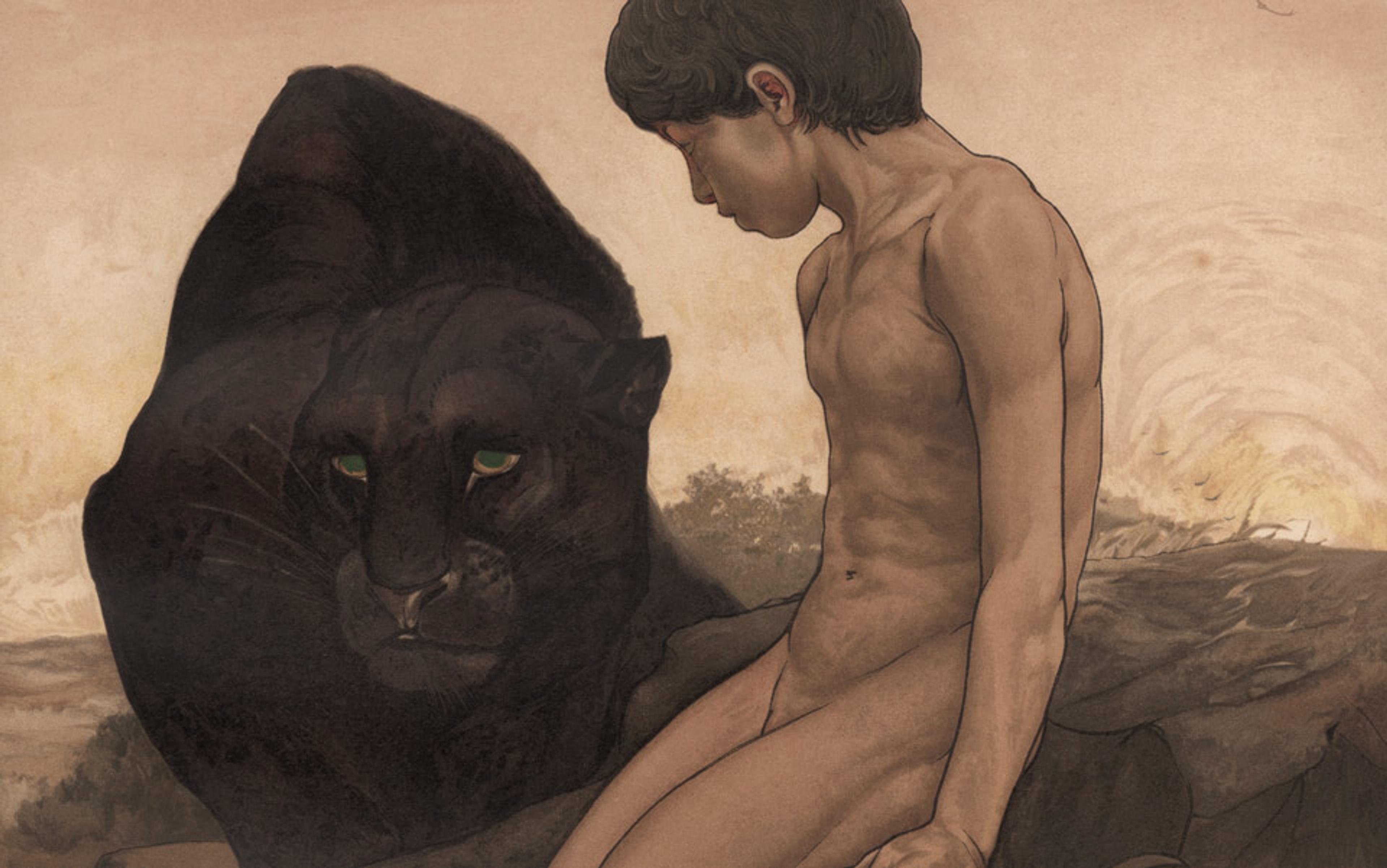

Descartes’ articulation of the animal as mere instinctual beast and his assertion of the total dominion of mankind ruled our interpretation of animals well into the modern era. And yet, despite Aristotle and Descartes, Montaigne’s vision of the talking animal reigns supreme in our cultural imagination. The annals of literature are filled with talking animals: Achilles’ horse Xanthos, the Cheshire Cat, Charlotte the spider and Wilbur the pig, Rat and Mole, Peter Rabbit, and George Orwell’s unpleasant pigs. The Monday-hating, lasagna-loving Garfield is, perhaps, the most honest of the bunch; he doesn’t actually talk, all of his communication is in the form of thought bubbles projected by his owner.

We memeify animals and set up Twitter and Facebook accounts for them: giving them the language we desperately want them to have

Not to be outdone, movies and television, too, are full of speaking animals: Mister Ed the horse, Babe the piglet, Nemo and Dory the tropical fish, Kermit the Frog, and the iconic Mickey Mouse. Indeed it seems at times that granting animals speech and translating the inner workings of their minds was the very reason the internet was invented. We scroll through picture galleries of slow lorises; watch YouTube videos of dogs saying ‘I love you’; ‘Squee!’ and ‘OMG!’ at a kitteh with delight. We memeify them and set up Twitter and Facebook accounts all essentially doing the same thing: giving them the language that we desperately want them to have.

Talking animal stories have their roots in a prehistory when, according to the literary scholar Egon Schwarz, professor emeritus at Washington University, consciousness had yet to distinguish between man and animal, ‘when people still believed in the possibility of slipping from one to the other, entirely according to desire or need’. And since then, talking animals have developed in a variety of rather amorphous ways to satisfy human desire; a kind of cipher for our own existential dilemmas.

Talking animals can provide us with joy and laughter. They can serve as a displacement for weaknesses and anger. And they can teach us very human lessons while simultaneously serving as a continual source of wonder. Think of Lewis Carroll’s menagerie of talking animals – from the White Rabbit to a Mouse offended by Alice’s bad manners – all of whom are animated by the wonder of childhood imagination. Or of Aesop’s animals designed to didactically instruct young minds toward the path of proper morality. Or of the canine narrator of Franz Kafka’s short story ‘Investigations of a Dog’ (1922), an ideal stand-in for the author’s alienated existence.

They can also serve to remind us of the idyllic pleasure of nature itself. Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902) teased out the beauties and attraction of England’s hedgerows and burrows to urban children whose own environment was increasingly polluted by early 20th century industrialism. The beautiful, untainted world of Peter Rabbit made Potter’s fantasy more potently pleasurable and the animals’ humanity seemingly more natural. Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908) served a similar purpose.

But if talking animals can provide an imaginary outlet, then they can also take on voices that appeal to our humanity, to beg for better treatment. Anna Sewell’s Black Beauty (1877) – written as an autobiography – is narrated by its eponymous horse, who tells of his happy times and also the abuse he endured while pulling commercial cabs. Disney’s heart-wrenching Dumbo (1941) and tear-jerking Bambi (1942) are animations that serve parallel ends: employing the talking animal to appeal to our higher human nature, a nature that animals supposedly possess only in fiction.

In 1749, the London-based Gentleman’s Magazine printed a particularly poignant example of this kind of literature: an opinion piece written by a hen in the final throes of life, the victim of a vicious pastime known as cock-throwing:

Hold thy hand a moment, hard-hearted wretch! If it be but out of curiosity to hear one of my feather’d species utter articulate sounds – What art thou, or any of thy comerades, better than I, tho’ bigger, and stronger, and at liberty while I am ty’d by the leg? What art thou, I say, that I may not presume to reason with tee, tho’ thou never reasonest with thyself? I appeal to thyself, who has known me for many months, What have I done to deserve the treatment I have suffer’d this day, from thee and thy barbarous companions? What have I ever said or done amiss? Who have I ever injur’d?

No matter how different, each genre of the talking animal exists on a continuum of the same fantasy. It is a reflection of a series of particular human desires, formed by historical needs and written onto the talking animal. Speaking animals provide us with the potential of an entirely different world – a world that is reminiscent of our own, even familiar, and yet still uncanny enough to maintain the fantasy. As the feminist scholar Donna Haraway wrote in 1978: ‘We polish an animal mirror to look for ourselves.’

But perhaps that mirror is more suited for a funhouse. The reflections and refractions of the ‘animal mirror’ can be as frightening and frenetic as one might expect from the human psyche. In some reflections, the animal is a joyous, riotous friend – a cat who, in the style of the popular blog, loves cheezburger. In other reflections, his brooding animality is still dangerous – a cat that needs to be strung up and publicly hanged for the protection of man. Indeed, the LOLcats of today and the so-called Great Cat Massacre of Paris of the 1730s – one hysterical, the other gruesome – are each distorted reflections in the same mirror.

Animals were condemned for falling foul of human law: murder, theft, even witchcraft

In his curious book The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals (1906), E P Evans traces multiple accounts of animal executions from Roman times well into the Renaissance: sows, horses, insects and donkeys all met their death at the hands of well-compensated executioners throughout Europe. Animals were condemned for falling foul of human law: murder, theft, even witchcraft.

But why torture and publicly execute a beast supposedly incapable of logos? The personification of condemned animals is striking precisely because it disturbs; the whole spectacle seems designed to yank them from the world of dumb, unthinking beasts; to demonstrate their capacity for human consciousness, one that entails an awareness of human morality, justice and language. After all, what’s the purpose of retributive justice if the offending party is unable to feel the weight of the anathema?

Perhaps the answer is found in the bloody history of 18th century Paris. During the Great Cat Massacre, apprentice printers captured and hung hundreds of cats. They did so as a gruesome form of protest – to hold someone accountable for their unfair treatment, their physical and financial suffering at the hands of their human masters. With little or no agency, apprentices put the ugly words of their masters into the mouths of innocent cats. The cat killers gave the felines the words they needed to hear and, though their intentionality was quite different, their need for animal logos belonged to the same fantastical world as the internet’s doge.

In the 20th century too, the public execution of circus elephants was a relatively common sight. Elephants who went on rampages, taking the lives of humans in their unhappy wakes, needed to be punished. Crowds demanded justice and they received a spectacle in return: Mary, a five-ton circus elephant who killed her new trainer, was hanged for the crime by heavy-duty construction equipment in 1916 in Tennessee; more infamously, Topsy, another circus performer gone bad, this time on Coney Island in New York, was fed poison, electrocuted and strangled in 1903, all the while being filmed by a crew from the Edison Studios. Dumbo, it seems, wasn’t all that fantastical.

We desire for animals to talk – both to share and to comprehend our values – and then assume that they understand our complex systems of justice and morality. We misunderstand and then ascribe punishment that belongs to the human realm of reason. We exercise what Descartes claimed is our right as humans – to exert dominion over beasts and order them dead. A real, actual animal, it seems, has little place in the fantasy world of the speaking animal.

But Cartesian animality, that bold line he drew between brutes and reasoning humans, has become more and more blurred. Humans now find humanity in the most troubled of animals. Animal rights activists rally to rescue a pit bull terrier that maims a child, or a cat that persistently attacks its owners. Rather than cart off such animals to the nearest shelter, owners beg for the lives of their beloved pets or call in specialists – experts who, ostensibly, possess a Doctor Dolittle-like power to translate animal speech, to communicate where others have failed. The most famous are, perhaps, the ‘Dog Whisperer’ Cesar Millan and his feline counterpart the ‘Cat Whisperer’ Jackson Galaxy.

In a recent episode of his Animal Planet TV show, My Cat From Hell, Galaxy was called to consult on the case of Lux, a 10 kg cat from Portland that made headlines when he attacked his owners, boxing them – and their newborn baby – into a bedroom from where they frantically called the police. Convinced that Lux just needed someone who could understand him, the couple called Galaxy, a man who seems able to translate the inner workings of troublesome and violent felines. During the episode, Galaxy proclaimed the erratically behaved cat ‘the sweetest boy in the world’. A few days after filming, the couple called Galaxy again: Lux’s behaviour had worsened. Galaxy transferred the cat to an ‘undisclosed location’, where Lux was diagnosed with feline hyperesthesia syndrome, a mysterious disorder treated by antidepressants. Galaxy continues to work with the cat, hoping to unravel his tangled inner world.

Humans seem to be constructing a linguistic bridge of sorts, one that when crossed will reunite us with Eden, where animals and humans live in the harmony of communication

What underpins shows such as this is the belief that cats – or any animal – can speak, but owners simply aren’t listening. Enter Galaxy, a man who is endowed with a special gift, a shaman-like magic to hear even the quietest of cats. ‘There are no bad dogs,’ Millan, the Dog Whisperer is fond of saying, ‘there are only bad owners.’ The animal now seems liminal – he speaks, but his speech is limited, his anger abnormal.

There is something innately animalistic about it all, a sense that Cartesian ideology tore us away from our animal past, from our evolutionary roots. In the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s estimation, the total separation from our history resulted in the ‘uncann[y] illness’ of modernity, a period of mourning for lost instincts. The fantasy of the talking animal is perhaps a modern Band-Aid of sorts – to speak to animals, to understand and be understood reinserts the animal into our very understanding of ourselves, of humanity. Lux the cat deserves to be saved because he is like us – misunderstood and in need of someone to listen to him. Humans seem to be constructing a linguistic bridge of sorts, one that when crossed will reunite us with Eden, where animals and humans live in the harmony of communication. But it makes one wonder if that bridge is being built on literary imagination or on reality.

The answer is as convoluted as it was when Montaigne first posed the question. On one hand, Temple Grandin, professor of animal science at Colorado State University, is the most public (if not the most respected) ambassador of a scientifically-based method of translation. Grandin has found great success translating animal speech, arguing that her autism is a portal to the animal mind. She has written extensively about her visual way of thinking, suggesting that autism’s image-based processing mimics the way animals process the world. On the other hand, we have Pixar animating a whole zoo of talking animals, as well as raccoons starring in big-budget comic-book movies, and BuzzFeed racking up millions of hits with such irresistible clickbait as ‘22 Of The Most Important Talking Animals You’ll Ever See’.

There is tension in these perspectives – they push and pull against one another in their approaches to resolution and toward animal language, but their ends are the same. Whether science or cultural fancy, the wish – the fantasy – is the same: to speak to animals, to hope that once that dream is realised, the Shiba Inus will actually speak doge. But perhaps it’s worth revisiting Montaigne’s question, to ask once again of ourselves and of our animals: who is playing with whom?