Shanshan’s $550 shoes came from her lover, but the soles of her feet, as hard as leather, came from her childhood. ‘We used to play barefoot in the village,’ she told me. ‘All the girls in the karaoke bar had feet like this.’

At 26, Shanshan has come a long way from rural Sichuan, one of China’s poorer southern provinces, famous for the ‘spiciness’ of its food and its women. Today her lover, Mr Wu, keeps her in a Beijing apartment that ‘cost 2.5 million yuan ($410,000)’, and visits whenever he can find the time away from his wife. In his late 40s, and an official with a massive state-run oil company, he was recently in Africa for six months developing an oilfield. Shanshan got bored and decided to improve her scant English by finding a ‘language-exchange partner’ online, which is how she and I became friends this spring.

Shanshan never referred to Wu as her boyfriend; he was her ‘man’, her ‘lover’, and occasionally her ‘uncle’. When she said ‘boyfriend’, she meant the man her own age back in Sichuan with whom she spent much of her free day exchanging text messages and whom she saw twice a year.

She’d walked the common path for country girls becoming mistresses, or ernai (literally, ‘second woman’). She’d gone to Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan, at 17, where she’d worked as a hostess at a karaoke bar at a hotel, before moving to Beijing to do the same. Her work involved entertaining men, including, if they paid enough, sleeping with them; that was how she’d met her lover, who’d offered to set her up after their fourth ‘date’.

It was an understandable decision on his part: Shanshan was sexy, merry, and smart. And for her, it was an obvious choice. An enormous amount of off-book money sloshes around Chinese business and officialdom, and some of it runs into handbags. As well as paying for her apartment and buying her gifts, Shanshan’s ‘uncle’ provided her with a living allowance of ‘about 20,000 yuan ($3,260) a month’. This was about the average for Beijing; in smaller towns, 10,000 yuan might be acceptable, or even 5,000. At the top end, a mistress might receive 10,000 yuan in spending money every day.

She was adamant that I never visit her apartment because she was surrounded by other ernai. Local estate agents target provincial officials and businessmen looking to put their money into Beijing’s property bubble, and the men fill up the apartments, bought as investments, with their women. ‘Half of the apartments are empty,’ she explained. ‘And the other half are full of girls. Everyone gossips. About money, about men. If they saw me with a foreigner, they’d talk about it for a month.’

Keeping a woman is common among powerful Chinese men. A study by the Crisis Management Centre at Renmin University in Beijing, published this January, showed that 95 per cent of corrupt officials had illicit affairs, usually paid for, and 60 per cent of them had kept a mistress.

Until recent crackdowns forced greater discretion, Chinese official life had two social circles. As the mobster Henry Hill puts it in the film Goodfellas (a key reference point for Chinese provincial officialdom): ‘Saturday night was for wives, but Friday night at the Copa was always for the girlfriends.’

At dinner with Shanshan, Xiaoxue and Lingling — two of Shanshan’s slightly older friends from Sichuan — they all agreed that the social circuit had disappeared of late, and that it had come largely as a relief. ‘It used to be a big part of work,’ said Xiaoxue, who was kept by a businessman back in Sichuan. ‘You had to make yourself look really pretty, and you had to make up to the most important people there, but not so much that the woman they came with would get jealous. But you still had to be…’ she started to flutter her eyelashes and raised her voice an octave: ‘Oh, you’re so clever! Oh, what important work you do! Oh, you’re really 55? You look so strong!’

‘That was how I came to Beijing,’ Lingling added. ‘I was with an official in Neijiang [in Sichuan], and they were hosting an inspection visit. One of the officials who was visiting really liked me, and he asked the guy I was with then to lend me to him, in exchange for connections. So I slept with him while he was in Neijiang, and then he brought me up to Beijing. But it didn’t work out between us.’

‘If you’re an official, you have to have a mistress, or at least a girlfriend,’ Xiaoxue said, ‘otherwise you’re not a real man. I used to have this friend who was a fake mistress. She was best friends with a gay guy — not a “duck” [male prostitute], just a normal gay guy — who was an official’s boyfriend. So the official would pay her to come out with him and pretend to be his mistress.’

Most mistresses are rural women who come to the job through other sex work, picked up at the karaoke bars, massage parlours and nightclubs that are often an obligatory part of business socialising. Their work is about emotions as much as sex. As with western punters who seek the ‘girlfriend experience’ online, Chinese men want the illusion of intimacy. ‘You have to be the girlfriend he wanted when he was 20,’ said Xiaoxue. ‘He wants to believe that you would be with him even if he wasn’t paying.’

She distinguished being a mistress from short-term hostessing, where you had to be a perfect servant, always putting the man’s needs first. ‘If you’re too nice to him all the time, he’ll know it isn’t true,’ Xiaoxue said. ‘If he looks at another woman, you should be jealous and sulk all evening until he apologises, so he knows you care.’

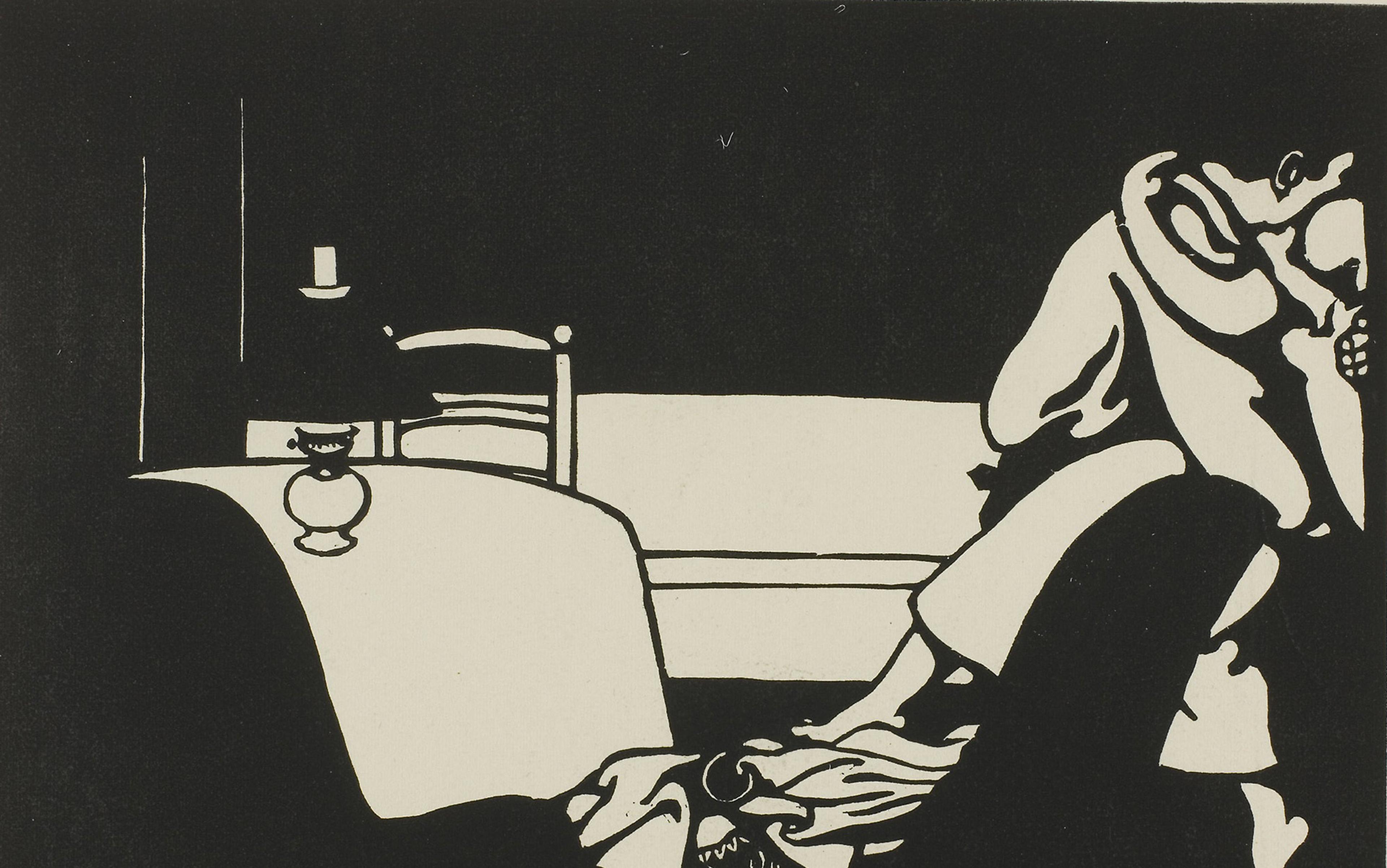

As the saying goes: ‘Old oxen chew young grass’

Zheng Tiantian, a social anthropologist at the State University of New York, worked as a karaoke bar hostess for two years in Dalian to research her PhD. ‘The most powerful men were identified as those who could emotionally and physically control the hostesses, exploit them freely, and then abandon them,’ she writes in her astonishing book on the experience, Red Lights (2009). But the women are equally mercenary. One of her informants comments: ‘I’d rather be a mistress than a wife, because you can make much more as a mistress.’

At the same time, both sides desperately seek real feeling, even as they try to conceal it from their contemporaries. In Red Lights, Zheng depicts men who value ‘real friendship’ and ‘sincerity’ in the women they pay for, and women who ‘inflict scars on their hands and wrists’ in order to ‘remind themselves of the ruthless game they are engaged in’.

Shanshan, who normally held her ‘uncle’ in affectionate contempt, became worried about his stay in Africa. ‘Six months is a long time,’ she said. ‘Do you think he’ll sleep with a black girl? I don’t think so; black girls all have AIDS. He wouldn’t cheat on me. Would he?’

The pragmatic approach of rural women leaves them better off than the educated urban girls who can also end up as mistresses. These urban women usually meet older men through regular work, and the relationship begins through genuine attraction. As they’ve maintained their ‘purity’ through not being involved in other sex work, they have a higher market value than the rural girls, and they’re more socially acceptable at high-end occasions.

A further distinction is sometimes made between ernai, who ‘know their place’, and xiaosan, ‘little threes’ (as in ‘third party’), who try to insinuate themselves between a lover and his wife with the aim of forcing divorce and remarriage. In practice, the terms are used interchangeably, but the difference matters especially to urban girls seeking to distinguish themselves from their rural counterparts.

‘Most xiaosan have a steady job and a higher educational background than an ernai. Xiaosan expect to marry the man because they’ve invested so much: their youth and their love,’ explains the 22-year-old founder of a website for xiaosan in Richard Burger’s Behind the Red Door: Sex in China (2012).

In my experience, many of the women expect never to marry their lover. One urban woman, Yu, told me: ‘I have money. My family is rich enough. I even have an apartment of my own. I just wanted to be his mistress so that he wouldn’t have other girlfriends. Apart from his wife.’

For Wen, now in her early 40s, with permed hair and lacquered nails, the limits had once been equally clear. As a young office worker in Beijing, she dated a north-eastern property developer worth tens of millions of dollars. ‘I knew he had to have a wife,’ she said. ‘I’m not stupid. But I thought I was his ernai, and that he loved me. Then I found that he kept three others around the city. I was his “fifth woman”, not the second.’

Shanshan and her friends seem less like victims, and more like players, astutely using the vulnerabilities of powerful men for their own ends

While a rural mistress might think first of her bank balance, an affair that starts emotionally (of which there has been an explosion) can have dramatic consequences. ‘I never imagined that the one I loved so much, the one who lived four years with me, would become my enemy,’ Ji Yingnan, 26, told The Independent newspaper in July this year after exposing her lover Fan Yue’s corruption. Fan was the deputy director of the State Archives, a position he leveraged to fund a lifestyle of extravagant spending and foreign trips with Ji.

When they met, Fan was middle-aged, and Ji was 22. As the saying goes: ‘Old oxen chew young grass.’ In all such relationships, the age gap is a depressing constant. In high-end restaurants, I like to play ‘Mistress or daughter?’ while looking at the seated couples. Even the waxen former president Hu Jintao was once rumoured to have ‘a mistress younger than his daughter’.

What’s more, some young Chinese women infantilise themselves, often with the aid of plastic surgery, to imitate the big-eyed heroines of Japanese cartoons. The aesthetic is popular with older men, who are aroused not just by the fragile look, but by affected sa jiao, ‘cute whining’, done in the fashion of a demanding child. In their private pictures, the girls look all of 14, while the men play alongside them in childish games or make faces at the camera.

I suspect that the image of innocence reinforces the men’s belief in their mistress’s sincerity, and allows them to believe that they’re not exploiting the woman, but offering protection. The urban women I talked to believed this far more than their rural counterparts. For many of them, the comforting image of a protective father/lover figure prevailed. ‘I thought I would always be safe with him,’ said one woman. ‘I liked him so much I even arranged a threesome for his birthday. And I paid the other girl!’

Chinese men’s penchant for mistresses is sometimes attributed to deep-seated cultural expectations, and it’s true that Chinese culture has rarely paid even lip service to ideas of male fidelity. Yet modern reformers often singled out concubinage as a sign of China’s backwardness, and pressed for stronger roles for women. Some, such as modern China’s first president, Sun Yat-sen, or its first chairman, Mao Tse-tung, did so even as they pressed teenage girls into their beds. Modern mistress-keeping might seem like a step back to the distant past. But this is just an excuse: any society as dominated by male leaders, and with as vast a chasm between the elite and the poor, sees the same exploitation of young women by powerful men.

Besides, Shanshan and her friends seem less like victims and more like players, aware of the limits of their work and astutely using the vulnerabilities of powerful men for their own ends. I admire them; in a system profoundly rigged against women, sex workers, the young, the rural and the poor, they have found a way to get what they can. Although it comes at an emotional cost, they seem to have taken control of their own fates. True, they live off dirty money: the cash conjured up by their lovers is frequently drained from the public treasury, or extorted in bribes from others. But so do hotels, luxury goods stores, estate agents, and the millions of others in China and the West happy to profit from the consumption habits of China’s elite.

The rural women I met were the lucky ones. They had been smart, cynical, pretty, witty, or simply fortunate enough to score the top prize — to escape, relatively young, from the brutality of China’s sex trade, dominated by organised crime, and with rape or assault a daily risk, into positions that granted them meaningful agency.

That said, the toxic intersection of power, money and sex holds its dangers. Mistresses can end up going to prison, or worse. In 2006, Xu Zhiyuan, a Beijing district official, paid his driver to strangle his mistress for arguing with him over ‘trivialities’. Duan Yihe, a senior Jinan official, had his nephew-in-law rig his mistress’s car with a bomb in 2007. And in 2011, Luo Shaojie, another Beijing district chief, had his mistress chopped up and murdered by his assistant after she threatened to expose his corruption.

The popular media portrays mistresses as ‘beauty attracting disaster’, and speaks of their ‘evil, poisonous nature’

‘I know girls who got beaten up,’ Shanshan told me, ‘but my man would never do anything like that. He has a good heart; he loves his daughters so much. He’s always showing me pictures of them and telling me how they’re doing in school.’

In an online age, there are other risks, especially at a time when the gender imbalance caused by selective abortion has meant a shortage of young women and a consequent cadre of sexually frustrated, bitter young men. ‘Slut-shaming’ is a regular habit on the Chinese internet: women exposed by angry ex-boyfriends or lovers’ wives have found themselves the target of a vast wave of abuse, including messages sent to their workplace or their parents.

The most recent ‘crackdown’ on corruption was launched with great fanfare by the new administration of the Chinese president Xi Jinping. But it has gone after such easy targets as hospitality budgets, official vehicles and foreign trips, while the real muscle has gone into hunting down dissidents, whistle-blowers and journalists who might actually threaten the powerful. As with anti-corruption campaigns of the past, mistresses make a convenient distraction. They feed the public appetite for scandal without challenging the way China’s power networks operate. The popular media portrays mistresses as ‘beauty attracting disaster’, and speaks of their ‘evil, poisonous nature’, as if the poor officials would never have tasted the apple of corruption without a woman to lure them on.

Yet beneath the public flaming, the pragmatism and cunning of some mistresses has made them folk heroes. One such is Li Wei: now 50, she worked her way up from the Vietnamese-Yunnan hinterlands to a personal fortune via a dozen or so powerful men. ‘They’re smart women!’ commented my respectable landlady. ‘These days, a woman has to look after her own bank.’ Women who expose their corrupt official lovers receive praise, ironic and otherwise. Even the Communist Party newspaper People’s Daily has admitted to a grudging admiration.

Still, the public crusades against mistresses, no matter how rhetorical can, in some cases, prompt early retirement from a dangerous profession. For mistresses from rural backgrounds in particular, the work is ultimately a means to an end. ‘One of my key informants was kept by a wealthy man for more than seven years,’ the anthropologist Zheng Tiantian wrote to me. ‘Her man bought her an apartment at the central location in Shanghai under her name, handed her a business under her name, and on top of that, bought her parents an apartment in a city next to their rural hometown. Her parents now work in their own supermarket that they opened. As for my informant, after she left the man two years ago, she went to a college to get a teaching certificate, when she met an ideal man [in her own words], and they were happily married last year.’ Zheng noted that most women ‘end the relationship with a sufficient amount of financial capital. They operate their own business while finding a man to marry.’

Or, like Shanshan, they’ll channel the bulk of their money into savings and investments. ‘Do you think mining’s a good industry?’ Shanshan asked me once. ‘My friend’s cousin has money in a Shaanxi mine, and she wants me to put 100,000 yuan in it.’ With other girls, she talked of stock markets, property, and how to get a Hong Kong bank account.

The social aspect of being a mistress can pay off big-time, too. After discovering her lover’s three other mistresses, Wen was able to translate the connections she’d made from socialising with his friends into her own property deals. Today she has ‘one house in Hainan, one house in Shanghai, and two houses in Beijing’, as well as a multi-million-dollar business of her own. Wen’s lover had made a generous final settlement on her because they had a son together. This is rare. Abortion is the norm, voluntary or otherwise.

‘You know about [the billionaire construction magnate] Wang?’ said my friend Li, a middle-aged businesswoman formidably tapped in to Beijing’s gossip networks. ‘He had sex with a karaoke bar hostess at a party a couple of months ago. Now she’s started sending him text messages saying she’s pregnant. But she’s in hiding till the baby is actually born so that he can’t force her to have an abortion. His daughter is at Harvard, but his son has cerebral palsy. So she’s saying that she can give him a healthy son, and she doesn’t want to marry him, she just wants to look after their son. With enough money, of course.’

‘I don’t blame her,’ said Li. ‘Women need to look out for themselves. Men always cheat.’