Sometime in 1932, Salvador Dalí met with the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. A deliciously queer photograph records them loitering together in a Parisian street, swaddled in fur coats so sumptuous that Liberace would have died of envy. Dalí’s is draped insouciantly across his shoulders like a black cape, his straggly collar-length hair lending him a vampiric air. But Lacan, distracted, has his hands shoved in his pockets, and the coat, a plush and stripy affair, mink perhaps, is a kind of nonchalant afterthought.

That Lacan should be a dandy is predictable enough to those familiar with his writings on the ‘mirror stage’ of infant development. For Lacan, no account of the ego is complete without narcissism, the gaze and the ‘specular image’ – the idea that selfhood is profoundly bound up with the ways in which we are seen from the outside. Lecturing to a captivated audience at the University of Leuven in 1972, grainy film footage records him as imperious, idiosyncratic and, it turns out, fond of pussy-bowed paisley-print chemises. Puffing at a fat cigar, his hands strain and curl with the intensity of his efforts at articulation: ‘Language,’ he says, ‘never gives, never allows us to formulate…’

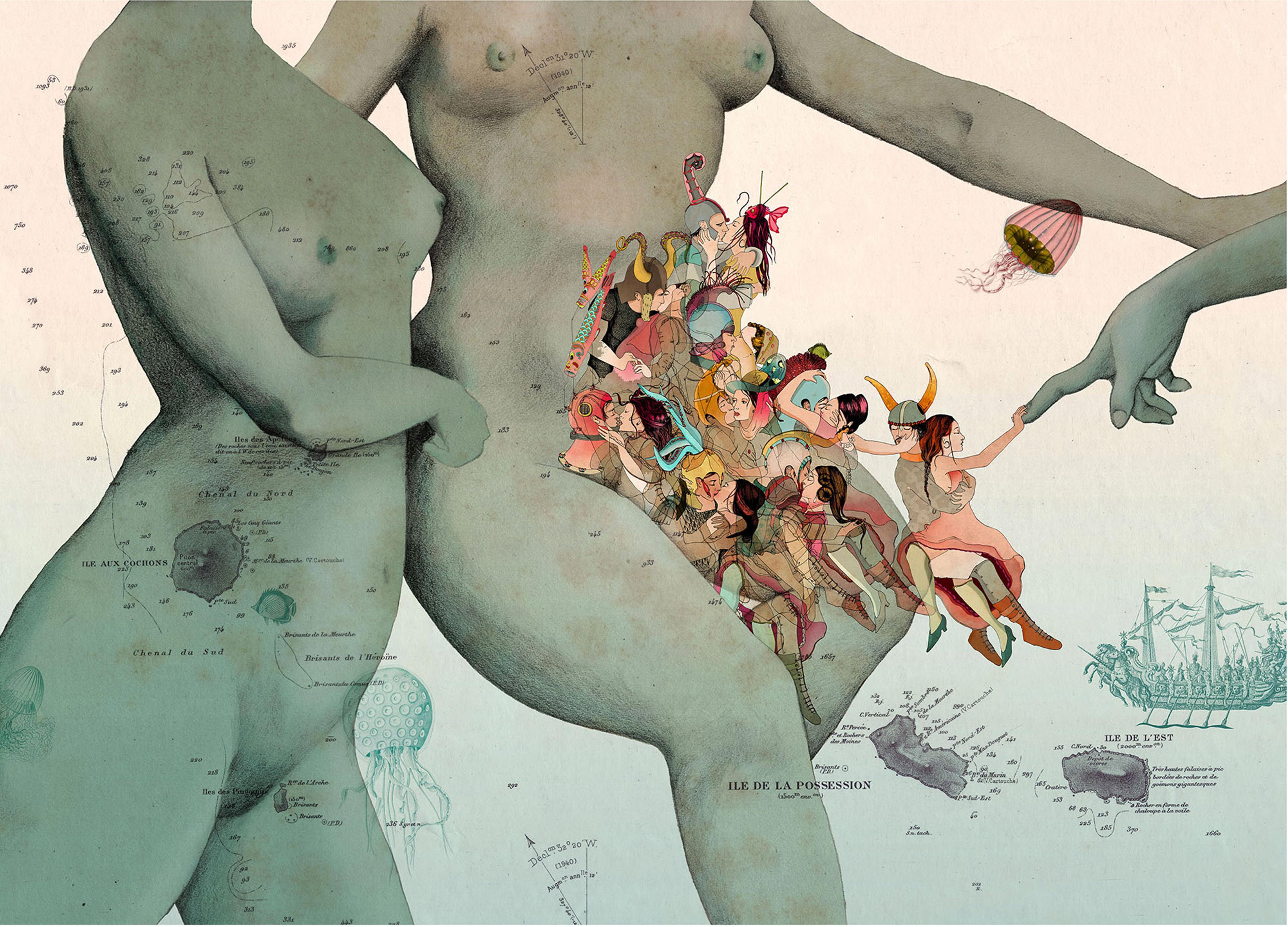

Where language falls short though, clothes might speak. Ideas, we languidly suppose, are to be found in books and poems, visualised in buildings and paintings, exposited in philosophical propositions and mathematical deductions. They are taught in classrooms; expressed in language, number and diagram. Much trickier to accept is that clothes might also be understood as forms of thought, reflections and meditations as articulate as any poem or equation. What if the world could open up to us with the tug of a thread, its mysteries disentangling like a frayed hemline? What if clothes were not simply reflective of personality, indicative of our banal preferences for grey over green, but more deeply imprinted with the ways that human beings have lived: a material record of our experiences and an expression of our ambition? What if we could understand the world in the perfect geometry of a notched lapel, the orderly measures of a pleated skirt, the stilled, skin-warmed perfection of a circlet of pearls?

Some people love clothes: they collect them, care for and clamour over them, taking pains to present themselves correctly and considering their purchases with great seriousness. For some, the making and wearing of clothes is an art form, indicative of their taste and discernment: clothes signal their distinction. For others, clothes fulfill a function, or provide a uniform, barely warranting a thought beyond the requisite specifications of decency, the regulation of temperature and the unremarkable meeting of social mores. But clothes are freighted with memory and meaning: the ties, if you like, that bind. In clothes, we are connected to other people and other places in complicated, powerful and unyielding ways, expressed in an idiom that is found everywhere, if only we care to read it.

If dress claims our attention as a mode of understanding, it’s because, for all the abstract and elevated formulations of selfhood and the soul, our interior life is so often clothed. How could we ever pretend that the ways we dress are not concerned with our impulses to desire and deny, the fever and fret with which we love and are loved? The garments we wear bear our secrets and betray us at every turn, revealing more than we can know or intend. If through them we seek to declare our place in the world, our confidence and belonging, we do so under a veil of deception.

Old, favoured clothes can be loyal as lovers, when newer ones dazzle then betray us, treacherous in our moments of greatest need. There is a naivety in the perilous ways we trust in clothes. Shakespeare knew this. King Lear grandly insists to ragged Poor Tom that: ‘Through tattered clothes great vices do appear;/ Robes and furred gowns hide all’ – even when his own opulence can no longer obscure his moral bankruptcy. Emerson too, mockingly corrects us when he writes: ‘There is one other reason for dressing well… namely that dogs respect it [and] will not attack you.’

Yet dress never promises to indemnify us from external assault or internal anguish. When the weaver invokes Khalil Gibran’s ‘Prophet’ to speak of clothes, the Prophet answers him dreamily:

Your clothes conceal much of your beauty, yet they hide not the unbeautiful. And though you seek in garments the freedom of privacy you may find in them a harness and a chain. Would that you could meet the sun and the wind with more of your skin and less of your raiment. For the breath of life is in the sunlight and the hand of life is in the wind.

Skin turned to sunlight. Exultation in exposure. But there is also no burying our real-world unloveliness in clothes: the ugly truth bears no dressing up. As Gibran tells us, dress can bind and constrain us; its regulated repertoire is a bondage estranging us from truer, freer, more naked realities. E M Forster wryly cautions us to ‘Mistrust all enterprises that require new clothes,’ but his own prim English Edwardian elegance was the keeper of his undisclosed confidence, sexual and otherwise.

Yet clothes can provide refuge, offering a canopy under which we shelter those anxieties and agonies from whose force we might otherwise cower like a naked king on a stormy heath. If there is despair at the back of life, it might be that dress helps us pacify and mute it. And yet to entrust to clothes the keeping of our secrets is a seduction in itself.

the jumper in which you exhale at the close of day, the slip that is the only thing pressed between you and your lover through the night

For some people, clothes are a disguise in which we dissolve, a kind of camouflage that allows us to keep something of ourselves in reserve, as though all we are and own for ourselves refuses to be articulated and shared in outerwear. For others, clothes are an acknowledgment of our alertness to life; we signal it in the deft and quirky ways we fix a belt, hang a tie, pin our jewellery. The clothes we love are like friends, they bear the softness of wear, skimming the curves and planes of our bodies, recalling the measurements and ratios of proportions they seem almost to have learnt by heart.

There are certain clothes that we long for and into which our limbs pour as soon as we find a private moment: the jumper in which you, at last, exhale at the close of day, the slip that is the only thing pressed between you and your lover through the long hours of the night. We need not wear our hearts on our sleeves, since our clothes seem already to know everything we might say and many things for which we could never find words.

Surprisingly, the discipline of philosophy has rarely deigned to notice the knowledge to which dress makes claim, preferring instead to dwell on its associations with disguise and concealment. In part, this has something to do with philosophy’s ancestral debt to Plato. Haunted by Plato’s anxiety over how to distinguish truth from its ‘appearance’, and niggled by his injunction to see beyond an illusory ‘cave of shadows’ to a reality to which our back is turned, philosophy’s concept of truth is intractably aligned to ideas of light, revelation and disclosure. We’ve learnt to revere the nakedness of truth and to deplore the screens and masquerades that keep us from it. The very figure of truth, aletheia (ἀλήθεια), is undressed in the Greek tradition, figured as a nude.

When Martin Heidegger reprised the classical notion of aletheia, he imagined nothing as stark as naked truth, but figured something more like a slow dawning realisation of that which is already there: an evocative kind of disclosure of the world to the beings within it. But philosophy’s revelations remain nonetheless at odds with the idea of dressing up.

In a journal entry of 1854, Søren Kierkegaard notes that ‘in order to swim one takes off all one’s clothes – in order to aspire to the truth one must undress in a far more inward sense’. Even for modern philosophy, then, the truth of self-knowledge seems to require renunciation, the stripping of metaphorical clothes, but also all material preoccupations and vanities. And there is an implicit elision here too: material preoccupations are a vanity. Those garish outward garments keep us from our naked inward truth.

Before Kierkegaard, Immanuel Kant dispensed with fashion, declaring it ‘foolish’. And yet his notion of ‘appearance’ has provided one of philosophy’s longest-standing concerns. Kantian thought distinguishes between the reality of things in themselves (noumena) and how they appear to us (phenomena), and the business of philosophy is the handling of this irreconcilability – that of a world that might exist on its own terms, and our limited abilities to apprehend it. Whereas Kant agonised over this distinction, Friedrich Nietzsche’s radically iconoclastic philosophy prized appearance as the means by which we play and overturn received ideas. In the figure of Dionysus, Nietzsche recasts truth as only ever a series of performances, appearances and surfaces behind which there can be no single, unchanging or inherent morality. The world appears in ever changing disguises, to be experienced aesthetically.

Although ‘appearance’ remains a resolutely perceptual and epistemological issue in philosophy, this concern is entirely disconnected from questions of physical appearance or dress. And yet to ignore the material reality of the clothed body is to deny something crucial to the ways human beings see and are in the world.

The notable exception here is Karl Marx. For him, dress naturally figured as part of a fully materialist account of the world. Clothes, it seemed, could embody the mystification of objects that he detected in modern culture. In the opening chapter of Capital (1867), it is a coat that exemplifies the distorted nature of all commodities in a capitalist society. Marx understood this first-hand. In the summer of 1850, he deposited his gentleman’s overcoat with a local pawnbroker, hoping to generate funds during one of several periods of penury. To his puzzlement, though, without appropriate dress, he found himself debarred entry to the reading rooms of the British Library. What was it about objects such as coats that they could magically open doors and bestow permissions? Not even a coat belonging to Marx himself could evade the ineluctable mechanism of capitalist exchange and value.

We sing the praises of shoes, dresses, jackets and bags as though they possess an inherent power; we give them stories, lives, identities

All commodities, including coats, were, it seemed to Marx, mysterious things, loaded with strange significances, drawing their value not from the labour invested in their production but instead from the abstract, ugly and competitive social relations of capitalism. The mundane, repetitive making of such objects exhausted workers, draining them of their will and vivacity, but Marx also noted the perverse way a commodity could, in turn, appropriate and imitate the qualities of a human being, as though it possessed a diabolical life of its own. Clothes represent that awful mimicry with particular acuity: think of the swaggering braggadocio of the newest trainers with their swishing insignias, or the dress that seems to possess its own flirtatious personality in its swing; even vertiginous heels that speak of a languorous life without exertion, worlds away from that of the worker who made them. Such garments enter the market, virginal and untouched, wiped clean of the prints of the working hands through which they have passed.

When Marx condemns the all-consuming commodity ‘fetishism’ of modern culture, he derives the term from the Portuguese feitiço, meaning charm or sorcery, and referring specifically to the West African practice of object worship, as witnessed by 15th-century sailors. To the fetish, worshippers attributed all kinds of magical properties that such objects did not possess in reality. In the same way, modern capitalism, it seemed to Marx, traded on the supernatural life of objects. Clothes are not exempt from eliciting this false idolatry. We sing the praises of shoes, dresses, jackets and bags as though they possess an inherent power, a spirit or soul; we give them stories, lives, identities, and in so doing blot out their real origins.

For Sigmund Freud – himself a notable wearer of high-quality, decently made three-pieces – clothes were not an object of intellectual enquiry per se, yet the idea of dress figures the premise of psychoanalysis itself, insofar as it concerns the relationship between the hidden and revealed. When Freud contrasts the manifest or outward content of dreams with their latent or submerged significance, he notes how the work of dreams is the binding together of inside and out, surface and depth. We speak, sometimes, of weaving dreams, as though dreams are spun. More to the point, our unconscious is clothed in the stuff of our dreams.

In Freud’s account, memories are fabricated. By invoking the phenomenon of ‘screen memories’, Freud radically challenged the integrity of infant recollection. Seemingly derived from pleasing early experiences, the screen memory records a relatively insignificant story in order to shield or protect a more catastrophic, hidden, import. The screen memory is not a ‘real’ memory, but one whose façade conceals another. When Freud uses the term ‘screen’, it is commonly taken analogically, to suggest a movie screen, a visual plane upon which an image is imprinted or projected and which occludes another, truer memory; but the term ‘screen’ can also mean a guard, or shutter. The screen is a textile; and just as dreams are bound and memory fabricated, the psyche too, as Freud understands it, is shrouded and veiled, layer after layer.

The word ‘fabric’ itself derives from the Latin fabrica meaning workshop or place of production, and faber – the artisan or maker who works with materials. It recalls the Indo-European dhab, appositely meaning ‘to fit together’. In the psychoanalytical scenario, analysand and analyst piece together the strands of the psyche, retracing forgotten pathways that lead from trauma to original experience, like Ariadne’s thread marking the route out of a maze. This piecing together, or fabrication of psychic life, entails a certain kind of creativity, even fictionality, albeit a fiction that is born of truth: the imaginative elaboration of dreams and writings revealed in talking cures and linguistic slips that lead us back to experiences we might be incapable of confronting.

We’re prone to disparage as crude the analogue of self with stuff, as though the substance of the soul might only be short-changed by the material things with which we seek to express it. And it is difficult not to read the diminution of dress in philosophy as part of a more general disdain for matters regarded as maternal, domestic or feminine. ‘Surface,’ wrote Nietzsche, is a ‘woman’s soul, a mobile, stormy film on shallow water.’ Relegating women to the shallows is, of course, to deny them depth, but the surface to which they are condemned is not without its own qualities: fluidity, responsiveness, sensitivity to a given moment or sensation. Female writers have always understood this. In Edith Wharton’s novel The House of Mirth (1905), Lily Bart concedes to herself the powerful truth of her passion for Lawrence Selden:

She was very near hating him now; yet the sound of his voice, the way the light fell on his thin, dark hair, the way he sat and moved and wore his clothes – she was conscious that even these trivial things were inwoven with her deepest life.

When we speak of things being ‘woven together’, we mean affinity, association, inseparability, but Wharton’s ‘inwoven’ intimates more: an intimacy so close that it is constitutive. Wharton’s contemporary Oscar Wilde quipped in The Picture of Dorian Grey (1890) that ‘it is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances. The true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible.’ With his dandyish green coats and carnations, Wilde teasingly nudges us towards the stark secularity of a new world in which divinity could be as readily located in dresses as in deities.

But Wharton’s insight goes beyond reference to a newly outward-facing modernity, and is more profound than the upturned paradox of a surface that could speak of the inner self. Lily is bound to Lawrence not simply by some romantic pledge of affection but in the particularities of his being, as though the tightest seam ran back and forth between her slow-gathered sense impressions (his voice, his hair, his clothes) and the interior life to which they seem to reach. As Lily is to Lawrence, we too are inwoven with the stuff of the world and the people to whom those things belong or refer.

Taking up this idea of a deeper, inwoven life, Anaïs Nin in Ladders to Fire (1946), writes of a woman in love:

weaving and sewing and mending because he carried in himself no thread of connection… of continuity or repair… She sewed… so that the warmth would not seep out of their days together, the soft inner skin of their relationship

Here, sewing is both material activity and metaphorical expression somehow woven together, in a kind of rising to the surface of the soul. We speak readily of the ways in which clothes express personality, but dress, costume, textile and fabric – the ways we wear, make, live in and think through them – are inwoven with our deepest life. The proposition here is not simply the idea that clothes might reflect that life, but that life itself takes place in clothes, and that the making of, caring for, passing on and wearing of clothes is steeped in our sense of selfhood, and registered in exquisitely intimate ways, by us and those around us.

the heel that cants the body, contracting your stride, the tie that stiffens your neck and straightens your spine

This is not to say that clothes are the self, but to suggest, exploratively, that our experiences of selfhood are contoured and adumbrated by many things, including clothes, and that the prejudices by which we disregard the concern for appearances or relegate dress to the domain of vanity, are an obstacle to a significant kind of understanding. As Susan Sontag says, contra Plato, perhaps there is ‘[no] opposition between a style one assumes and one’s “true” being… In almost every case, our manner of appearing is our manner of being.’

Perhaps we simply are in clothes. And in clothes, our various selves are subject to modification, alteration and wear. This happens in clumsy ways – the glasses you hope might lend you new seriousness, the reddened lips that mimic arousal – but also in innumerably subtle ways: the heel that cants the body, contracting your stride, the tie that stiffens your neck and straightens your spine. Some garments constrict and reshape us physically, but also, sometimes, emotionally. And there are garments we can feel, that itch and chafe, that make apparent the difference of their textures to that of the surface of our skin, as though we and they are not one. In these, we are alert to the experience of being in our bodies, in a way that seems at odds with the rest of the world gliding past, apparently immune to discomfort. In such garments, too, we are always alert to the ever-present physicality of our bodies.

By contrast, there are clothes we wear almost imperceptibly, that are light or diaphanous to the point of being hardly seen or felt, as though we are sheathed in air. There are clothes that we are so accustomed to that we go about our business with barely a thought to the bodies they encase. If the self is somehow experienced, then perhaps there are moments when we strive to be seen and others when we seek a certain kind of invisibility. We wax and wane in the things that we wear. In clothes, there are always possibilities for difference and transformation.

Yet if those possibilities for transformation are exciting, they are also dangerous, dislodging the security of a self that could believe itself shored up, imperturbable and unchanging. How, for instance, could it be that we so easily emulate others in what we wear, as though our selves were interchangeable, indistinguishable, altogether indistinct? We make light of costumes and fancy dress, yet their very possibility contests the privileged exclusivity of personhood. In costume, after all, there is betrayal, the dispelling of an enchantment rather than the casting of a spell, an exposure of the pretence that is authenticity: if I can glibly dress like you, how then are any of us ourselves?

The anxiety of authenticity is never far away from dress. We seek clothes that ‘are us’, and there is an implicit insolence in the ready-to-wear, off-the-rail garments we rifle through, that unsettle us in suggesting that our precise measurements might be generic, predictable and average. Still, there can be immense tenderness in the ways our clothes tell the stories of a self subject to all kinds of alteration: the bitter-sweetness of ‘growing’ into a coat inherited from a long-gone parent; folding away the maternity dress you will never have cause to wear again. Sometimes, there is only anguish: the blood stain on a T-shirt from that most terrible of days. Clothes mark our mutability. They parallel the vicissitudes of our lives in their subtle shifts of colour and sheen, and they stretch over time.

But there is a promise in dress, too. The French philosopher, Hélène Cixous writes of designer Sonia Rykiel and the perfect dress – the dress in which one might, at last, be comfortable, almost natural (if not in your skin, then at least in your dress): ‘The dress that comes to me… agrees with me, and me with it, and we resemble one another… The dress dresses a woman I have never known and who is also me.’ This dress is a dream, or a dream dressed up as a dress, casting the wearer anew but also affirming an account of themselves that they gladly snatch up for display. In this dress, Cixous is unplagued by the anxieties of her body, her beauty, her age and her sex – the sense of perfection or completion it imparts, is almost divine:

I enter the garment. It is as if I were going into the water. I enter the dress as I enter the water which envelops me and, without effacing me, hides me transparently… And here I am, dressed at the closest point to myself. Almost in myself.

Here there is no rupture or discontinuity, only fabric that feels like the body itself, transmitting the truth of the self through it, without impediment. In an odd way, perhaps this dress of dresses aspires to a kind of transparency or an invisibility, whereby we might be seen as we really are, at our very best, in a light that is undiluted, perfectly truthful, and just.

Some of us might believe we possess such a dress, a rare thing lovingly preserved and only carefully exposed to the light of day; others reach for its possibility and find in every new purchase a pretender, sensing it forever slipping from our grasp or gaze, like the faces of the dead that come to us only in dreams. Perhaps the power of the right dress necessarily comes only rarely, like hard-won self-knowledge, the shining truth of which cannot stand too much scrutiny. Philosophy might have forgotten dress, but all that language cannot articulate – the life of the mind, the vagaries of the body – is there, ready to be read, waiting to be worn.

Shahidha Bari hosted a special meditation on the secret life of clothes at HowTheLightGetsIn London, the world’s largest philosophy and music festival, and a friend of Aeon, this September. Participants were invited to pause and think about the place of clothes in their lives, and were asked: Can a philosophy of living be wrapped up in a winter coat? Can we see a suit not just as an object, but as an idea? HowTheLightGetsIn returns to Hay-on-Wye, Wales, next May for more philosophical fun. Tickets are available here: howthelightgetsin.org/hay