Sarah was in her late teens when it first happened. A normal Thursday, it was early morning and pitch-black outside. The wind rattled the trees, branches rapping the windowpanes like a nervous visitor at the door. She could feel it was nearly time for her to get up, and heard her parents moving around downstairs.

As she opened her eyes for the first time, something changed. A dark realisation – two, in fact.

She couldn’t move her body. And she wasn’t alone.

Something in the corner of her bedroom was waiting there. It was watching her. Something very old, almost primal. It emanated a vital sense of malice.

Later that day, she sat her father down at the kitchen table. ‘OK dad, I need you to tell me about ghosts.’

What Sarah (not her real name) experienced that morning was sleep paralysis, a phenomenon that affects about 7 per cent of adults. It happens because, when we awake, our muscles aren’t always ready – even if our minds are conscious and alert. It is a natural consequence of the muscle paralysis most of us experience when in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, in the shallow waters of our sleep cycles in the early morning. Without sleep paralysis, we might act out dreams and nightmares (people for whom that does occur – those with REM sleep behaviour disorder – generally have poor health as a consequence).

Estimates vary, but about half of everyone who experiences sleep paralysis will have hypnagogic hallucinations at the same time. Hypnagogia refers to unusual experiences around the boundaries of sleep: the shout of a name, a flicker out of the corner of your eye, or even a sudden touch as you drift off. The most common hypnagogic experience in sleep paralysis is this mysterious ‘feeling of presence’: the sensation that someone is there, without any clear sensory evidence or even any input from the outside world. And the presences that come during sleep paralysis are often of the worst kind – pure malevolence, as if something had just stepped straight out of a nightmare and into your bedroom.

Feelings of presence (FP) are, at their core, just that: feelings. While we routinely think of hallucinations as auditory or visual in nature, the FP experience involves the mere sense that someone else is present without a visual, auditory or sensory cue. This isn’t about hearing or seeing someone, nor does it involve a touch on your shoulder. People land on this term – presence – because they don’t know how else to describe the sensation. Something basic and invisible, a feeling you know if you’ve had it, but struggle to put into words for someone else.

Despite the challenge of describing presences, there’s increasing awareness that they may actually be relatively common across a range of different contexts. For example, feelings of presence are reported by lots of people with Parkinson’s disease, alongside other kinds of hallucination. FP reveal themselves in a huge number of survival stories, particularly for mountaineers, climbers and polar explorers, in which they are known as the ‘third man’ effect. And for people who are grieving, the loss of a person can often be associated with an ongoing sensation of presence.

I first came across the phenomenon of the unseen presence through working with people who hear voices (what some might call auditory verbal hallucinations) as part of a project at Durham University. We would often be told about a particularly uncanny feeling: voices that could be there without speaking – as if they carried a presence of their own.

I wanted to know more about what that really meant because it didn’t fit with most models for how we understand hallucinations. Hallucinations are perceptual experiences without any corresponding sensory input from the world outside. They are usually distinguished from other phenomena like illusions, in which there is an input that you misinterpret; haze on the horizon that creates a mirage is an example of an illusion. But a feeling of presence isn’t supposed to involve any perceptual content. It lacks the stimuli on the outside, but it’s not even clear what the feeling is on the inside.

How can you hallucinate something without any sensation at all? This is the paradox at the heart of felt presence.

There are a few different ways you can approach this question. It could be that people don’t really mean they can actually sense someone else there. For example, some people swear that they know when they are being watched, as if they had eyes in the back of their head. It’s probably fair to say that many researchers would not consider this an actual phenomenon, but it could be that FP and the feeling of being watched reflect the same thing: people feeling uneasy in new or uncertain environments. Heightened anxiety, a chill down the back of your neck, a sense of paranoia – each of these could contribute to something like a presence.

Another possibility is that felt presence may be a secondary interpretation, prompted by other unusual experiences. Take hearing voices as an example. If you were used to hearing a disembodied voice all the time, you might come to expect or believe that a person is there, even when silent. It wouldn’t take much to give someone that feeling. Many of us might hear a noise in another room and go and check in case someone is there, with a vague and uneasy feeling that the noise could have been made only by a person. For a fleeting moment, a sensory cue such as a sound might give rise to the distinct feeling that an unseen person is there.

When you look at accounts of felt presence, it’s surprising how many involve some sensory content around the edges. Survival stories are actually rife with this. A presence that leads someone back from the edge of the ridge might have the visual outline of a figure – or a shout into the tent wakes someone just in time – and from that, people feel a presence with them. These encounters are often described as presences because the sense of a visitor lingers, but they might start in a more tangible sensory way.

The ‘third man’ comes from Shackleton’s account of being joined by a phantom companion

If this was the case – if, in fact, all presences were just these secondary feelings, responses to unusual sensations – then there would be no paradox. People wouldn’t just feel it, or just know; they would be having the sensation because they have already sensed something else. Case closed.

But if that was what was happening, it’s debatable that there would even be a term for the experience. When people describe presence, they don’t linger on the sights or the sounds; they focus on the hidden person, the unknown other. The point of the story often isn’t that they heard something odd and thought someone was there – the crux of the matter is that the feeling could just be there, on its own. If we think about why people bother to describe an experience as unusual as this, we have to consider that something else is going on; something beyond the ordinary senses.

Ernest Shackleton’s trans-Antarctic expedition in the HMS Endurance, c1914-17. Photographed by Frank Hurley and courtesy the State Library of New South Wales

And ‘pure’ presences can exist. The original ‘third man’ itself comes from Ernest Shackleton’s account of being joined by a phantom companion when crossing the island of South Georgia in May 1916, at the end of the ill-fated HMS Endurance expedition to Antarctica. Shackleton and two other men – Frank Worsley and Tom Crean – all described feeling joined by one other. ‘It seemed to me often that we were four, not three,’ wrote Shackleton. The presence didn’t speak, and wasn’t seen. It was just there.

If presences can occur without other sensory content, another possibility is that this isn’t an interpretation, but it is still a kind of belief – namely, a delusional belief. Since presence was first documented clinically, there has been a question about whether this kind of experience reflects a form of perception, or a belief; a feeling or a knowing. There is a tradition in the study of psychosis that lots of unusual beliefs are ways of making sense of unusual perceptions, such as voices or visions. We could call this the catch-all explanation for presence: if it’s not perceptual, it must be a mistaken belief.

There are good reasons to take belief seriously when we think about accounts of presence. Along with the clear overlaps with things like paranoia, feelings of presence are often interpreted via the lens of belief. The presences of grief and bereavement are closely related to people’s expectations, hopes and longings, while the presences of survival situations are often given spiritual explanations. It wasn’t by mistake that Shackleton and Worsley described their companion as ‘Providence’.

But for a range of reasons, a ‘belief-only’ account doesn’t seem to fit. Presences can occur without any unusual beliefs: FP in Parkinson’s, for example, can occur in relative isolation from strange beliefs or interpretations. And even when people do have strong expectations of FP, the presences that arrive don’t always fit. I’ve interviewed long-distance rowers who hope for one visitor and get an anonymous ghost, and religious people with sleep paralysis who get visited by demons, but don’t see their night-time visitors as being part of any spiritual realm they recognise. Presences are often surprising.

Ultimately, many accounts of presence just don’t sound like beliefs. People might oscillate between the language of ‘feeling’ or ‘knowing’, but they often go on to describe bodies and sensations: mirror people, phantoms in the room, figures stepping out of the self. One person with psychosis described it to me like ‘the feeling when someone steps over your grave’, and another simply as ‘a thickness in the air’. This is an experience that people feel viscerally, in their bones, with every fibre of their being. It’s a ‘felt presence’ – the clue is in the name.

That brings us back to where we started, with the presence paradox. How do you hallucinate something without the five senses?

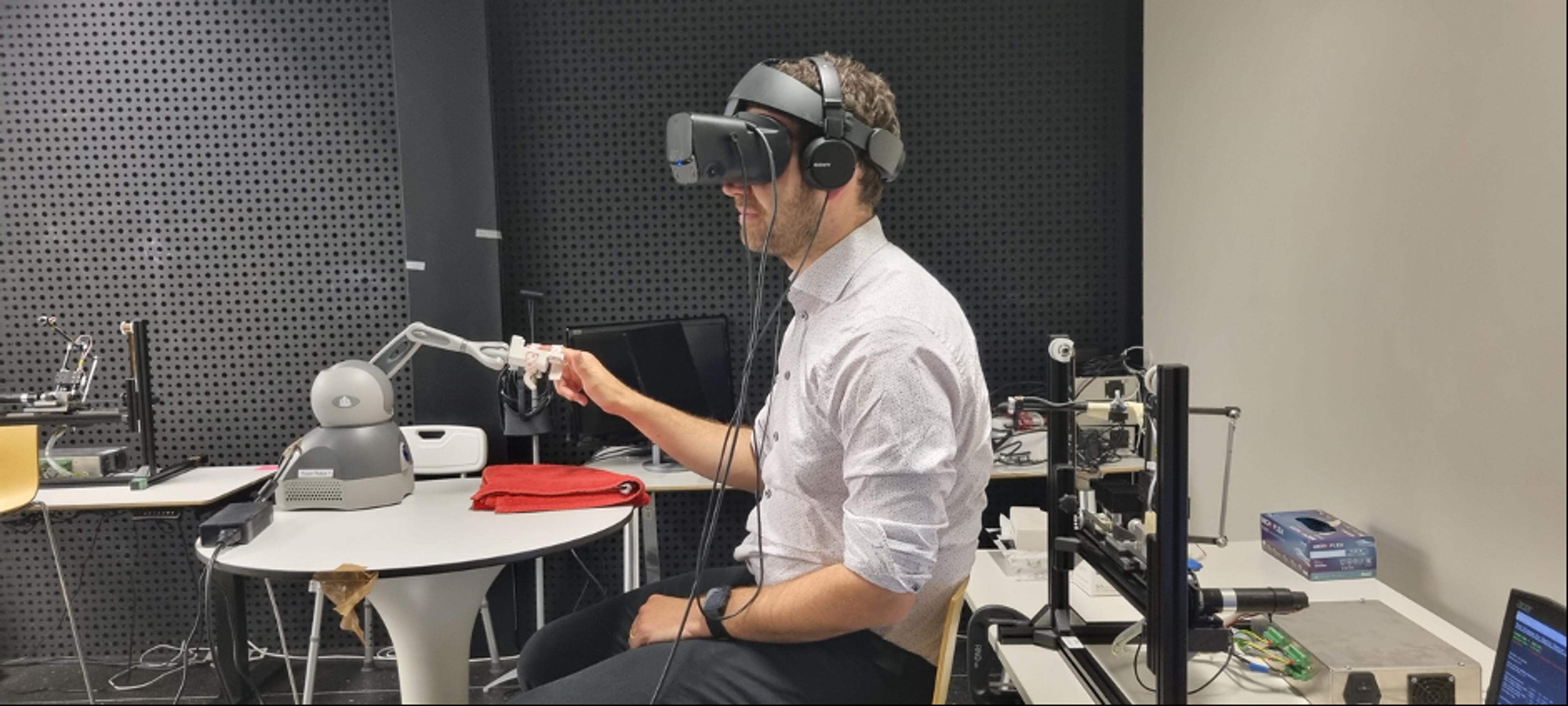

‘Ever Felt A Ghostly Presence? Now We Know Why’: this New Scientist headline accompanied the publication in 2014 of a study led by the cognitive neuroscientist Olaf Blanke at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland. The research relied on a robot matching one’s movements – and apparently inducing presences experimentally in healthy people. The paper also included a new theory about how it worked; how the sense of an unseen other might emerge from mind and brain by perturbing our very own sense of self.

In December 2022, I travelled to Geneva to visit Blanke’s lab. It was time to meet a presence of my own.

I arrived on an overcast Tuesday morning and was met at reception by Fosco Bernasconi, a Swiss postdoctoral researcher in the lab. Bernasconi’s work focuses on Parkinson’s disease, and in 2021 he published the first study to use the ‘presence robot’ with this group of people. People with Parkinson’s were particularly susceptible to the phenomenon, with the procedure inducing them to laugh out loud, check over their shoulder or suddenly twitch in surprise.

I found Bernasconi in a gleaming atrium of glass, steel and climbing plants. The scale of it was almost absurd – something like Gattaca meets Glass Onion. Bernasconi explained that it had originally been built for a pharmaceutical company, which then abandoned it only a few years ago. A group of universities had taken over the space instead, repurposing it for what they needed. As we walked, he pointed out the MRI scan facility, and the new site where they were installing another suite of scanners. Out of the atrium and through multiple sets of double doors, we passed down a series of blank, grey corridors, no sign of what was to come next. Instead of light everywhere, there was a vague sense of foreboding, and I was reminded of those unsettling first-person computer games when you are constantly waiting for the next jump.

We eventually emerged from the corridors and moved into the offices of the lab, where I sat down for a chat with Blanke. We got talking about the lab’s current work, where it’s going next, and what the PhD students are trying out. Most of it still revolves around this particular procedure: the robot that can make you hallucinate.

Presences could be induced by electrically stimulating a brain area known as the left temporoparietal junction

It works like this. Imagine you sit with a glove-like handset in front of you. You are told to shut your eyes, place your hand in the contraption and push with your finger into the air in front of you – repeatedly, in a random motion, as if you were punching in a never-ending pin code, but constantly forgetting what the numbers should be.

So far, so mindless. But when you start doing this pointing action, you get something else. A touch on your back at the same time. You touch to the left a bit, and the touch goes with you. Touch to the right, and it’s there too.

Before long, you might start to feel odd, like it’s you somehow touching your own back from behind. This illusion comes from the synchrony of our sensory and motor cues, and it relies on the same logic as other well-known effects, like the rubber hand illusion – in which participants start to experience a fake rubber hand as part of their own body.

But then it starts to get weird. The touch on your back is slightly delayed, falling out of sync with you. Like it wasn’t you all along. Like someone else is there.

This was the effect the New Scientist headline was describing. Across their series of experiments, Blanke’s team demonstrated that this procedure seemed to conjure presences. They first found that a subset of people would spontaneously describe a felt presence when the asynchronous touches started to happen. Then they asked directly via a questionnaire: 75 per cent of participants confirmed that they felt more like another person was there. And they showed that it affected people’s number estimations, too. If participants were told to track how many people had come into the room during a new version of the experiment – with the number constantly varying across trials of the experiment – those who felt the presence also estimated more people being in the room with them.

In 2006, Blanke and colleagues had shown that presences could be induced by electrically stimulating a brain area known as the left temporoparietal junction (TPJ), a meeting point in the brain for two lobes: temporal and parietal. This area is notable because it’s one place where we are thought to combine information about the senses, our bodies and space; where we feel we are, at any moment in time. It’s the map of us, in other words.

The newer research with the robot extended that idea to show that it’s our integration of touch, motor movements and proprioception – the sense of our bodily location – that needs to be disrupted for the effect to occur. If you put those things together, we are pretty good at keeping track of ourselves. But if you disturb that, via electrical stimulation or unexpected touches, the self seems to go astray. The sensations we expect to happen don’t happen; the things we thought we controlled suddenly aren’t happening according to plan. And we start to feel that ‘It’s not me… so it must be someone else.’

Throughout the rest of the day, I met Blanke’s team. From the neuropsychologist Jevita Potheegadoo, I learnt about the ‘phantom boarder’ – a phenomenon in Parkinson’s disease that is closely related to presence, but subtly different. People feel a presence but specific to a place; usually upstairs, at home, when they are downstairs. The creeping intruder was something moving around up there. I had come across this before when talking to people with psychosis; presences would often be tethered to them, but sometimes would be tied close to home.

Last of all I met one of the PhD students in the lab, Louis Albert. I’d been told, if I wanted to see the procedure, I had to talk to him; he was testing out some cool new techniques using VR to measure the presence effect in different ways. I met Albert back on one of the long, grey corridors between the lab and the atrium. We passed room after room, until finally he opened a large metal door. As he did so, he said: ‘This room is full of robots…’

And he was right. In a large space about the size of a squash court, it looked like an army of half-finished robots had taken over a high-school drama studio. Mechanical arms hung limply, resting on wires and scaffolds, as if they could spring back into action at any moment. I began to wonder which of them would be my companion.

It took a few minutes to get set up, with a VR set wedged awkwardly on my head. When we were ready to go, a virtual Albert appeared on the screen to explain what was about to happen. And then the touches began.

At first, it was simple. I pushed, and got pushed back. I tried to be consistently random, moving my hand to a new spot each time. And every time, the robot prod was with me. It felt like I was in control, and I was concentrating on being a good participant.

Then slowly… a drag. A delay. A touch not quite in the right place. I placed my finger, and again it was like it didn’t hit the target properly. The touch behind me felt like it got later and later, as if it was slow on the uptake. I felt it happen and thought ‘I need to slow down, I am doing it wrong,’ but this made the problem worse. With each course correction, the gap got bigger, as if time itself was slowing down. It was like trying to do something everyday and familiar – unlocking your front door, maybe – but with the finesse of having a bad hangover. I definitely felt different, even annoyed. The process had been jarring, unsettling somehow.

The sweet spot was different for different people; it depended on how they interacted with the environment

But did I feel a presence?

Reader, I did not. To me, it felt like a dance with a bad partner; a joint task where the coordination was all wrong. It did feel like something was distributed beyond me – but it wasn’t a body, it was more like a responsibility. I was working with someone else, and together we were doing a bad job. It was like a team-building exercise gone wrong.

At this point, I have a confession to make. I think I am the least hallucination-prone person ever. I have interviewed people who have had imaginary friends since childhood, and spoken for hours with mediums, seers, and ayahuasca psychonauts. But absolutely nothing unusual has ever happened to me. I am the world’s worst hallucination expert.

So if anyone wasn’t going to feel the presence when encountering this robot, it was going to be me. But that is true of other people too: some people are hugely susceptible to the effect, but not everyone has this feeling. The procedure isn’t a one-size-fits-all thing.

Naomi Lea is a designer who made a series of installations at the Bartlett School of Architecture at University College London that were inspired by Blanke’s work. When I interviewed her, she emphasised to me that every person found a different installation worked for them: some found a presence in some phantom hands under a lightbox, while others saw wind chimes move in a room without wind. The sweet spot for presence was different for different people; it depended on how they interacted with the environment around them.

What the work from Blanke’s team shows is that presences can be conjured by perturbations of the body. If we lose track of where we should be, or what belongs to us, another phantom body can emerge. This is the first answer to the presence paradox; feeling another in the absence of sensory evidence can be the misplaced feeling of our own muscles. That’s why people feel it in their bones; it’s a phenomenon truly of their own bodies.

But when and how that works depends on our sense of self and our interaction with the space around us. Where we stop and the world begins is a constantly negotiated thing. Once you start looking for presence, you see so many different situations that can challenge that boundary: sleep paralysis, survival situations, psychosis, bereavement. But whether a presence emerges likely depends on what a person brings to a specific situation.

The key question for felt presence isn’t how it’s possible to feel something without the senses. That’s just the first question. The bigger question is whether we need one explanation, or more. When we consider voices that cannot speak, or the presences of survival scenarios, the challenge is to work out is whether displaced bodies are all we need, or whether something else might be going on too. The presences that haunt sleep paralysis, that dwell in psychosis or provide solace in grief – these are phantoms that are full of emotion. During the creative process, characters might feel like they take on presences of their own; continuing beyond a narrative or speaking for themselves. And some kinds of imaginary companions – such as the new phenomenon of tulpamancy, where the conjured friend has great agency – are described as truly being there, as if looking out through the eyes of the person experiencing them. All these instances show how some presences seem to come from the mind, or even the heart, as much as they might plausibly come from the body. We researchers need to understand whether this is one kind of presence, or many. It might require more than one robot to solve the true paradox of presence.