Up until recently, there existed a place where pretty much everyone who’d ever lived and then died was thought to dwell. This place is known to Catholics as Purgatory, a kind of eschatological holding pen where the souls of the deceased are cleansed of their sins by fire, thus allowing their ultimate entry into Heaven. Yet over the past few decades, Purgatory – and the presumably billions upon billions of people residing within it – have all but disappeared from view, with barely an anguished whimper.

Perhaps this quiet disappearance is down to the fact that, contrary to the fervent belief of millions of Catholics over the past millennium, Purgatory may not actually be best understood as a concrete place located in this world after all. In recent years, the Roman Catholic Church hierarchy has distanced itself from such a view of Purgatory, with John Paul II stating in 1999 that ‘The term does not indicate a place, but a condition of existence,’ a view subsequently echoed by Pope Benedict XVI’s statement that:

Purgatory is not … some kind of supra-worldly concentration camp where man is forced to undergo punishments in a more or less arbitrary fashion. Rather it is the inwardly necessary process of transformation in which a person becomes capable of Christ, capable of God …

The Catechism of the Catholic Church doesn’t necessarily clear things up, stating that:

All who die in God’s grace and friendship, but still imperfectly purified, are indeed assured of their eternal salvation; but after death they undergo purification, so as to achieve the holiness necessary to enter the joy of heaven. The Church gives the name Purgatory to this final purification …

The New Catholic Encyclopedia (2nd ed, 2002) keeps its options open, describing Purgatory as a ‘state, place or condition’.

My interest as an anthropologist is in neither the theological debates surrounding the existence and nature of Purgatory, nor in the historical discussions surrounding its emergence and its correlation with economic and social changes over the past millennium. Rather, what intrigues me is the nature of the hold that Purgatory – despite its recent decline – retains; in its way of both constituting and being constituted by certain kinds of relationships; and in the traces these relationships have left behind: the social life of Purgatory.

In my travels from ice-cold loughs in Ireland to balmy lakes in southern Italy, from volcanoes in Iceland’s frozen north to blazing Mount Etna in Sicily, I’ve been captivated by the very thing the Church hierarchy has always feared: the materialisation of Purgatory in a specific concrete place in this world. What consequences does this materiality have for people’s engagement with their dead? What role has it played in Purgatory’s seemingly irreversible decline? And what value might be found in our secular age in such an esoteric and seemingly obsolete doctrine?

I ask these questions for I’ve come to believe that, although Purgatory is undoubtedly on the wane, we should perhaps not be too quick to hold its wake. My travels to and through Europe’s purgatories, and my encounters with those for whom it remains an area of concern, have revealed to me that there is still much to be learned from these traces of a Purgatory that has outlived its Church. Perhaps not from Purgatory’s eschatological architectures nor from its theological paradoxes, but from something far more profound: what it means to truly love one another in the fullness of our mortality.

While the idea of an intermediate state after death is present in many religions – Buddhism has its bardo, Judaism its Sheol, Islam its A’raf – Purgatory stands out precisely for its ambiguity, an ambiguity rooted in the fact that there is scant scriptural evidence for its existence.

The notion of a material place where people are cleansed of their sins in a literal fire no longer resonates

A great deal of theological weight is placed upon a particular verse from St Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians: ‘If any man’s work shall be burned, he shall suffer loss: but he himself shall be saved; yet so as by fire.’ Purgatory’s very reality thus stems at least partially through a negative proof: if Heaven is fully perfect and free of sin, and our souls bear the stain of sin, how are these stains cleansed to allow for our entry into Heaven? There must, logically, be some kind of mechanism, and it is around the logical necessity for the cleansing of sin that Purgatory developed, a theological black hole subsequently filled in by the flames of a millennium of cultural imagination, from Dante to Shakespeare, from Yeats to Beckett, and in a myriad popular practices around the world.

What these practices seem to condense around is a desire to materialise Purgatory, to locate it in this world, a popular desire constantly in tension with the Church’s desire to place Purgatory in the spiritual, immaterial realm of piety. Such a suspicion or distaste for material and literal versions is not simply a recent post-Vatican II response to growing secularisation, but has endured throughout Christianity’s long history. As far back as St Augustine, the Church hierarchy feared what the great historian of Purgatory, Jacques Le Goff, called ‘the danger of making the other world too material’.

The notion of a material place where people are cleansed of their sins in a quite literal fire simply no longer resonates with contemporary sensibilities. This is a big change. As the historian Robert Orsi has described, Catholicism has witnessed a broad shift away from a more material, literal understanding of the spiritual towards an abstract, immaterial one. This is a process that Purgatory has not escaped, enduring what has been described by historians of religion such as Diana Walsh Pasulka as ‘dematerialisation’ and by Guillaume Cuchet as ‘spiritualisation’. And without this material foundation, the entire doctrine seems to be dissolving.

Even among the most devout Catholics, adherence to the doctrine of Purgatory has all but disappeared. As one priest in Naples admitted to me, the whole Purgatory thing had become ‘a bit embarrassing’. I’ve never heard Purgatory mentioned by priests in any of their homilies, from Scotland to Italy, from Ireland to the United States; fewer and fewer masses are held for the souls in Purgatory; and prayers for the anonymous souls seem to be becoming less and less frequent. It seems as though popular faith has finally weaned itself off its material crutch and is now ready to embrace the abstract and the spiritual more directly.

Yet if Pasulka is correct that Purgatory’s ‘physicality … is its best advocate and its most problematic feature’, we’re left wondering what has this physicality achieved? Because for many, if not most, believers over the past 1,000 years, Purgatory has been understood, erroneously or not, as synonymous with a place – a concrete, visitable place located here on this Earth, where the sins of the dead would be burned away before their final entry into Heaven. Most importantly, the dead’s primary source of relief from this suffering came through the love and prayers of us, the living.

My first glimpse of the sustaining role of love in the apparatus of Purgatory came not from a Catholic but, indirectly, a Protestant. Among the many Protestant objections to the doctrine of Purgatory has been the futility of prayers for the dead, the arrogance of thinking that we, the living, could in any way bypass God’s judgement and influence the fate of the dead. Yet it is upon these prayers for the dead that the entire logic of Purgatory as a lived, social phenomenon hinges – the belief that death does not sever us irreparably from those we love. For Catholics, prayers for the dead allow one to both ease their suffering in Purgatory and to accelerate their passage through it. Thus love for the deceased is not founded solely upon memory, but rather upon a continuing social life of mutual care and assistance.

A few years ago, I was living in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides – a long chain of islands fervently Protestant in its northern half, and devoutly Catholic in its southern half. I was sitting in the kitchen of the parish house in South Uist, one of the southernmost islands in the chain. Sheep grazed right up to the kitchen’s windows, undeterred by the rain that battered the glass. Father Donald placed a plate of chocolate digestives and Kit Kats alongside the milky cup of tea he’d made me. He told me a story that in many ways triggered my interest in our relationship with the dead.

Years previously, he had been the priest to a parish in Stornoway, on the Isle of Lewis, many miles to the north. Although both Lewis and South Uist shared the same Scottish Gaelic language, they differed in terms of religion: Lewis was a resolute stronghold of the Free Church, a Calvinist denomination famed for the strictness of its ways. South Uist, on the other hand, was, and had always remained, devotedly Roman Catholic. As a Catholic priest in a Protestant heartland, Father Donald had not found Lewis an easy place during his time there, ministering to a small and isolated congregation of Catholics who’d nearly all ended up in Lewis from other places.

The dead are petitioned on behalf of the living in return for certain kinds of ‘refreshment’

There was a housekeeper in the parish house at Stornoway, and she, like almost everybody else from Lewis, belonged to the Free Church. One morning after making tea, the housekeeper approached Father Donald and rather nervously asked him for a favour. She asked him to pray for her son, a young man who had died the previous year. Father Donald was taken aback: ‘Of course I’ll pray for him, but why don’t you pray for him yourself?’ Now it was the housekeeper’s turn to be taken aback: ‘Oh no, I could never do that. The Church doesn’t allow it.’ The Protestant prohibition on prayers for the dead was so deeply rooted that it constituted a dam that the flow of grieving love could not overcome, a love that could be channelled only through the prayers of another.

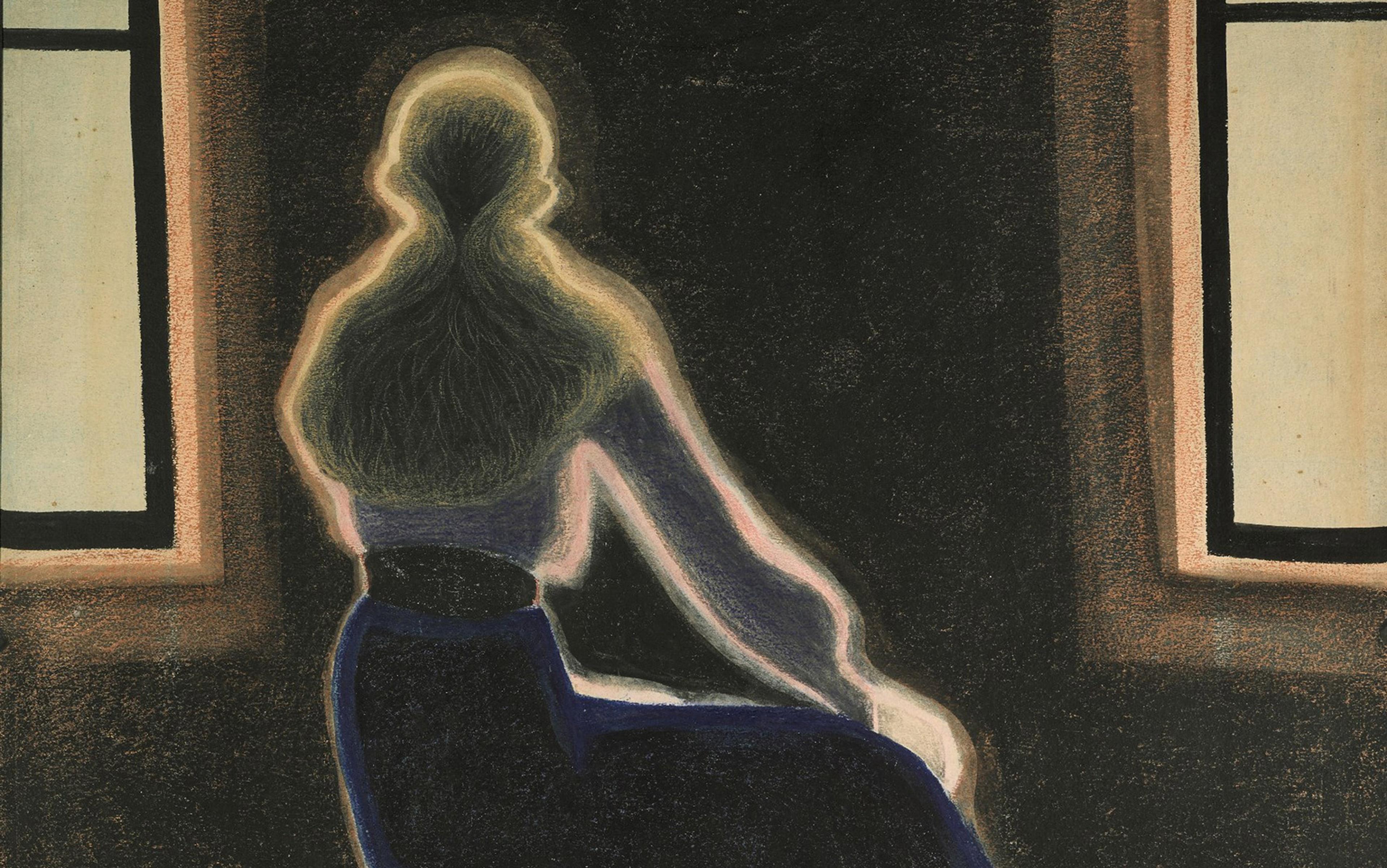

This flow of love from the living to the dead becomes visible in the city of Naples, where I was living some years later. It is here in Naples that the practice of prayer for the souls in Purgatory reaches its greatest contemporary expression. Throughout the ancient centre of the city, small shrines consisting of three-dimensional dioramas of Purgatory can be found embedded in the walls of its narrow, twisting streets. Red and orange flames engulf an ensemble of tiny terracotta figurines – portraying a young woman with flowing hair, an old man, a priest – all raising their arms towards Heaven and the assistance of the Virgin Mary, the queen of Purgatory. People from the surrounding neighbourhoods stuff passport photos of deceased loved ones into the glass cases of these dioramas to gain them, too, some relief from the flames through proximity to Mary’s divine intercession, an intercession accompanied by the prayers of all those walking past.

It’s perhaps through this emphasis on proximity that the twin pillars of Purgatory – materiality and love – come together. The enduring value of proximity in Christian ideas of materiality has a genealogy stretching back to its earliest days. The medievalist Peter Brown describes the cult of saints emerging from the desire of the faithful to be as spatially proximate to a saint’s relics as possible, in both life (through pilgrimage) and death (through burial close to the shrine). Proximity allows for the possibility of a direct transfer of grace, a kind of spiritual and emotional contagion and, once imagination has shifted into these spatialised terms, a topographical and material understanding of Purgatory follows.

These Neapolitan dioramas of Purgatory are partly geared towards prompting each passerby to pray for the souls represented but, in some parts of the city, this logic is reversed: the dead themselves are petitioned for intercession on behalf of the living in return for certain kinds of ‘refreshment’. This refreshment would consist in prayers, songs, flowers, chocolates, cigarettes, etc, and the requests would either involve healing, getting a job, finding a spouse, or getting pregnant. Devotees would adopt a particular soul through the simultaneous adoption of its material counterpart, a skull, which would be polished, cleaned and placed inside a small wooden box. And here again we see the emphasis on giving the immaterial and spiritual a material and physical location, on connecting them to the stuff of this world.

Scholars of this ‘Cult of the Souls in Purgatory’ have noted that it increases in intensity in periods of great loss, such as the plague epidemic of 1656, which wiped out about half the population, the cholera epidemic of 1836, which killed some 20,000 people, and in the years following the Second World War. The skull stands as a proximate, material surrogate for a missing body, both a place to go and an object to touch. Yet the soul attached to each skull is not that of the deceased loved one but rather an anonymous soul, a soul whose identity may be glimpsed only in dreams. How might devotion to an anonymous soul benefit the soul of a loved one? As the anthropologist Ulrich van Loyen has pointed out, by helping the anonymous souls, devotees can count on their help for the souls of those whom they themselves have lost. Again, it is love – in this case a love for the known, routed through the anonymous – that animates Purgatory.

Not surprisingly, this praying not only for the dead but to the dead was all too much for the Archbishop of Naples who banned the cult in 1969. Nevertheless, Neapolitans have a proud history of ignoring clerical edicts, and the cult has continued in a more subdued manner in several locations across the city. Not least of these is the astonishing Cimitero delle Fontanelle located just north of the city centre. A huge underground cavern excavated from the soft volcanic rock, the cemetery contains a huge number of skeletons: old ones, primarily from the great cholera epidemics that swept Naples during the 19th and 20th centuries.

It is really an ossuary rather than a cemetery per se. Stack after stack of bones, neatly ordered into piles of femurs, and so on. And then the skulls, countless skulls aligned on top of one another in neat rows, with those nearest the front all enshrined in small wooden boxes with their ex-voto inscriptions on the top. It is a place that must be seen to be believed, so deeply moving that it reduces Ingrid Bergman to tears in a scene from Roberto Rossellini’s movie Voyage to Italy (1954). Many of these sites are now primarily tourist attractions, and Purgatory has become a highly visible part of the tourist boom the city has witnessed over the past decade. Yet one cold November evening, down a dark side street away from the torrent of tourists on via dei Tribunali, I witnessed three old women praying and pushing flowers into the foot-level grate that accesses the crypt of the church and the anonymous skulls of those souls in Purgatory enclosed within.

In many ways, then, the dead here perforate the world of the living, and the living the world of the dead. Their presence is visible in the shrines on every street, in the crypts of the numerous churches both closed and open, and in the death notices covering pretty much every square inch of wall. Perhaps it was this porosity between life and death that Walter Benjamin and Asja Lacis had in mind in their 1925 essay on Naples. And the very concept of Purgatory is itself premised on porosity – the idea that the living and the dead remain part of the same social world, that our prayers can pass easily through the veil of death, a communion of saints that transcends the barrier of mortality.

Mount Etna does indeed destroy and damn, yet it also purifies and rebirths

The distressing knowledge of our loved one’s suffering leads to the question of where, if these flames are real, does this burning take place? Where precisely is Purgatory? Clues can be found in the fact that the imagery, iconography and imagination of Purgatory overlap with, and build upon, that of Hell: the burning flames, the mocking demons, the endless wailing of the damned. They are to all intents and purposes identical, bar one crucial difference: you will, eventually, leave Purgatory; the damned therein are not truly damned, but destined for rebirth in Heaven.

Nowhere is this blurring of the boundaries between Hell and Purgatory clearer than the slopes of Mount Etna where I was to find myself earlier this year. The distant peak kicks out a plume of dark grey smoke that soon materialises as black sand in my hair and covers my sweat-soaked skin. Swifts drop through the blue sky screaming, screaming as if they too were burning in Purgatory’s flames.

For many centuries, Etna’s spewing of burning lava and constant emission of pained groans led it to be identified with both Christian and pre-Christian versions of a fiery underworld. And with its solidification in the Middle Ages, Purgatory, too, staked a claim. Walking around the many shrines carved into the solidified lava around the volcano’s base, my guide Carmelo explains that Etna does indeed destroy and damn, yet it also purifies and rebirths. He shows me the tiny yet perfect Etna violets emerging from the scarred, black aftermath of its frequent eruptions. And he takes me to the reconstructed church of the Madonna of the Sciara (sciara being the Sicilian word for this solidified lava), rebuilt after its destruction in the great eruption of 1669.

Inside the church is a miraculous statue – the Madonna of the Sciara – which was carried down the mountain in a stream of molten lava as the original church containing it was destroyed in flames. Thirty-five years later, in 1704, a local peasant woman dreamed of the Virgin standing above a particular spot far down the slope and, upon waking, started digging, only to find the statue preserved, purified and sanctified. It now stands again within the restored church, these days a major pilgrimage throughout region.

An entire wall of the church’s vestibule is covered in photos of babies, miraculously born through the intercession of the Madonna of the Sciara, her statue itself miraculously reborn. Once again, Purgatory is sustained by love across generations: its potential not just for the rebirth of the dead, but the birth of the living. ‘This is what Purgatory means to me,’ says Carmelo as we leave the church and head back down the mountain, ‘the birth of true life after purifying fire.’

Etna is but one among many candidates for Purgatory’s earthly location; the deep tectonic groans emitted from the volcanic isle of Stromboli were another strong possibility for some; and even beyond the limits of the Catholic world, in the vast icy reaches of the north, the Icelandic volcano of Hekla was often feared as the door to Purgatory.

A somewhat less likely candidate, but one that, according to Le Goff, marked Purgatory’s ‘literary birth certificate’, is a small hole in the earth of a very small island on a fairly small lake in Ireland, Lough Derg in County Donegal. Legend has it that, many years ago, while wandering through the Irish countryside, St Patrick encountered Jesus, who proceeded to show him the aforementioned hole in the ground and explained that, if he were to spend a night there, he would be purged of all sin and thus able to bypass Purgatory altogether. A 1,000-year literary tradition built up around this spot describing the adventures of pilgrims from all over Europe brave enough to face the ordeal of the demons in the hole by now known as St Patrick’s Purgatory.

Despite several unsuccessful attempts by Church authorities to close it down, St Patrick’s Purgatory attracted ever-growing numbers of pilgrims. The site today continues to be a place of pilgrimage throughout the months of June and July, but the three days and two nights of fasting and prayer are no longer framed as literal immersions in Purgatory, but rather as a time of ‘prayer and reflection’. Yet, as I came to realise during my own participation in the pilgrimage, this ‘dematerialised’ version of Purgatory – nobody claims any longer that this is the actual door to an actual Purgatory – still builds upon prayers for the dead, on care for the loved and the lost.

‘But the real problem with cremation is that – nyarrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr – and that’s why I want to be – nyarrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr.’ This is the first time in my 20 years as an anthropologist that somebody has insisted on using power tools while being interviewed, and I can’t help but wonder if the high-pitched whine of the jigsaw biting into plywood isn’t timed to coincide with the more theologically precarious parts of Pepe’s argument. I’m standing in the street outside his carpentry workshop trying to talk to him about his role as custodian of an edicola – a small shrine built into the wall, in a street around the corner from his workshop.

We are back in Naples, in the Quartieri Spagnoli – the Spanish Quarters – a neighbourhood in central Naples whose tight, grid-like structure of narrow streets dates back to its previous incarnation as a military barracks during centuries of Spanish Bourbon rule. Children on mopeds scream up and down the street at our backs, inching us forward into the workshop. I try again: ‘So what’s the problem with cremation?’

‘It’s just too fast, troppo veloce,’ says Pepe. ‘It’s true that we come from ashes and we will return to ashes, but it’s a process that has to take time. It doesn’t count if you do it straight away with cremation. And besides, where would you go to pray for your dead?’ He has already told his children that he wants to be buried in a collective tomb in the colossal Poggioreale cemetery on the other side of the city. For Pepe, it seems to be a problem of proximity. Without a dead body, where will his children go to pray for him?

Purgatory retains its lingering hold, because of something that goes far beyond religion: our love for one another

In Naples, and throughout the Catholic world, the steady decline in Purgatory has gone hand in hand with the rise of cremation; material bodies and material places incinerated into thin air. The cultural historian Thomas Laqueur warns us against drawing too hard a correlation between religious belief and funeral practices, but I can’t resist seeing the parallels: the immediacy of a direct jump to Heaven deprives the dead of their dependency on the living, just as the material immediacy of material annihilation deprives the living of a corpse to visit. In both cases, the relation between living and dead is severed. They don’t need our intercession if they’re already in Heaven; they are removed from us both physically and spiritually. For people like Pepe, it is proximity – both in space and time – that constitutes the basis of our communion with the dead, our joint participation with them in the communion of the saints or, as one priest put it in a homily on All Souls’ Day, ‘the joy of walking together’ (la gioia di camminare insieme). When the dead no longer need us, our bond to them is weakened.

The decline of Purgatory would seem to be terminal. In a broader context of increasing secularisation, it would appear to be an increasingly obscure component of a religion itself on the retreat. But rather than focus upon Purgatory solely as an institution or as an historical object, I’ve tried to show how Purgatory was made possible, and in some places retains its lingering hold, because of something that goes far beyond it, far beyond Christianity and far beyond even religion itself: our love for one another.

It is surprising how in otherwise such detailed, erudite and imaginative accounts of Purgatory, both historians and theologians so rarely mention this love, a love without which Purgatory is nothing but a dead, inanimate doctrine, a corpse laid out on the table awaiting dissection. Perhaps the literary scholar Stephen Greenblatt comes closest when he writes:

The brilliance of the doctrine of Purgatory – whatever its topographical implausibility, its scriptural belatedness, and its proneness to cynical abuse – lay both in its institutional control over ineradicable folk beliefs and in its engagement with intimate, private feelings.

It is Purgatory that, in many ways, makes sense of our prayers for the dead, and our prayers for the dead that make sense of the vitality of our continuing relationship with them, a relationship consisting of mutual care rather than of memory alone.