Just a few years ago, infection with the hepatitis C virus guaranteed a slow and certain death for many. Available treatments were effective in about half of all patients, and the side effects could be awful. Things changed in 2014, when a new medication called Harvoni was approved to treat the infection. With cure rates approaching 99 per cent and far fewer side effects, the medication became an instant blockbuster. Sales topped $13.8 billion in 2015.

But then an odd thing happened – sales began to drop precipitously. Harvoni, in conjunction with four other hepatitis C drugs, is projected to generate only $4 billion this year, a three-fold decline in as many years. Part of this decline is due to new competitors entering the market. But according to analysts at Goldman Sachs, another reason could be that the drug’s cure-rate erodes its own market.

In a private report leaked to news outlets in April 2018, the Goldman Sachs analysts caution against investments in pharmaceutical or biotechnology companies aiming to develop outright cures, and cite Harvoni as a case study. It’s a simple point to make – if profit is your goal, then a product that eradicates its own demand might not be a wise investment.

Though it sounds bad, it’s not a nefarious perspective. The overwhelming majority of pharmaceutical development occurs in the United States or other market economies abroad, where private industry is the force majeure that drives progress. And industry, as much in pharmaceuticals as in any other business, is at the game for revenue rather than the greater good. Much benefit can and has come from this arrangement, but it’s something of an externality to the powerful incentive to make money.

The predominance of the market in US healthcare has taken plenty of flak for promoting profit over quality, and for crescendoing costs.

But there’s a deeper set of issues surrounding how the market influences – or distorts, maybe – the very bedrock of healthcare and medicine. In a system driven primarily by profit, certain diseases or treatments must languish simply because they’re not lucrative. And how can such a system do other than favour revenue over patients?

One of the most compelling examples of how profit incentives can distort drug development has its roots, oddly, in the popular television series Quincy, M E (1976-1983). In an episode that aired on 4 March 1981, the well-known American actor Jack Klugman played a gritty Los Angeles medical examiner investigating the suicide of a boy with Tourette’s syndrome, a neurological disease that causes uncontrollable tics and verbal outbursts. On the show, Congressional hearings took place to investigate why no drugs were available for the disease. Mock representatives from the pharmaceutical industry explained that many diseases, including Tourette’s, were thought to be sufficiently rare that there was no financial incentive to develop medications.

The episode struck a national cord, and Klugman was invited to testify before a real Congressional panel investigating the same issue – non-existent treatments for rare or ‘orphan’ diseases. The New York Times featured Klugman’s testimony. Public opinion rallied, and Congress passed the Orphan Drug Act in 1982.

The bill provided incentives for the pharmaceutical industry to develop treatments for rare diseases, including large subsidies for development costs, accelerated regulatory approval, and seven years of market exclusivity – a temporary monopoly. The bill has largely been considered a success. Before its passage, only 10 drugs existed for orphan diseases; by 2014, that number had grown to more than 450.

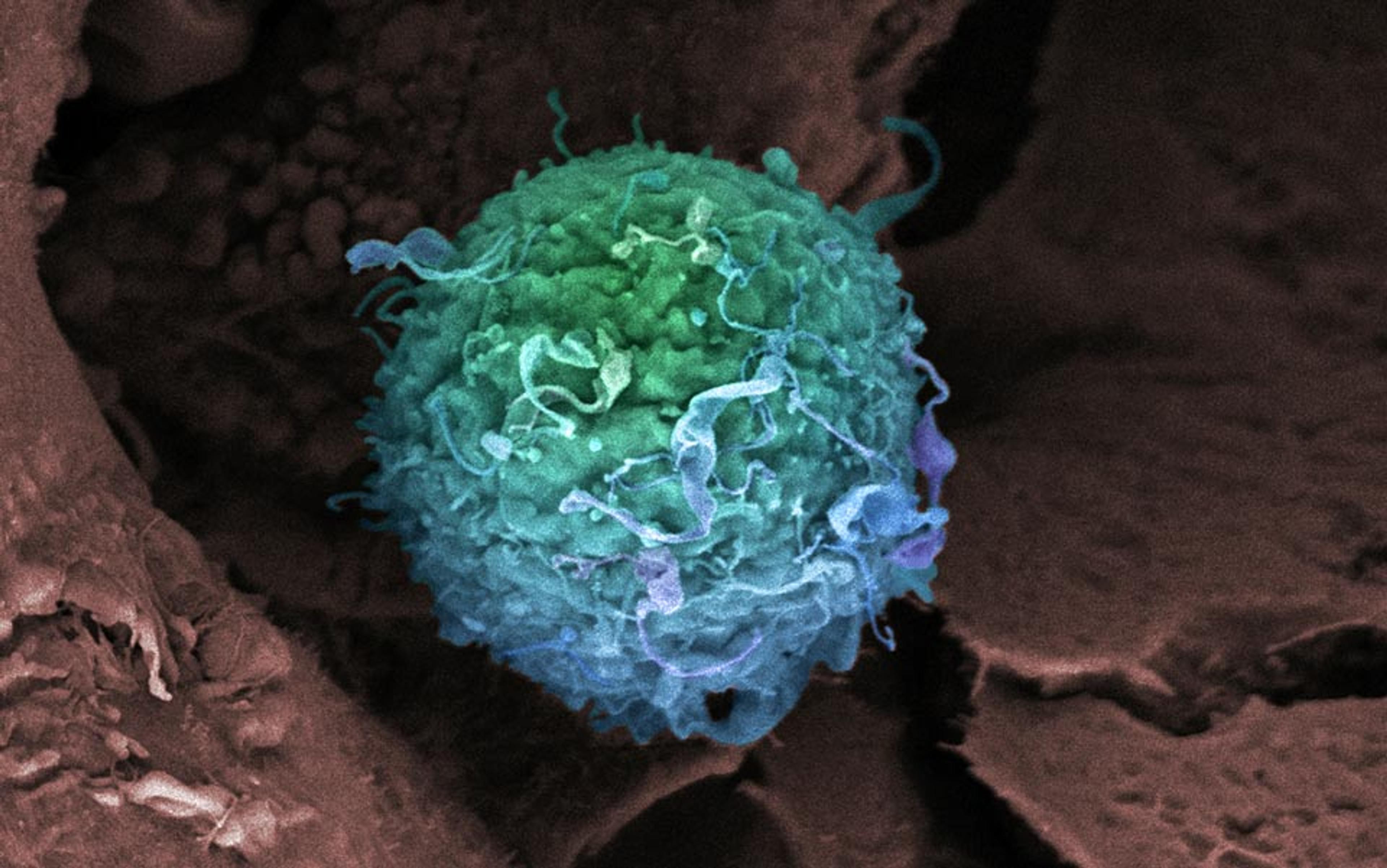

By other measures, though, the Orphan Drug Act has been too successful. The Act’s incentives, coupled with the fact that pharmaceutical companies can set any price they like for a drug in the US, have made the orphan market astonishingly profitable. A leukaemia drug called Gleevec became one of the first orphan blockbusters when it debuted in 2001 for an unprecedented $26,400 per year, demonstrating just how lucrative orphan drugs could be. Today, Gleevec sells for nearly $150,000 per year, with total sales approaching $5 billion. But it’s not even among the 10 most expensive orphan drugs, many of which sell for over $500,000 per year. An analysis by Thomson Reuters found that the ‘economics and investment case for orphan drug development’ was ‘more favorable than for non-orphan drugs’. Put another way, pharmaceutical companies make way more money creating orphan drugs than they would in developing better treatments for more common maladies.

Orphan drugs illustrate how financial incentives distort the development of treatments in ways that don’t always provide the greatest benefit

Industry has got the message. By 2010, 30 per cent of new drug approvals by the FDA were for orphan drugs, even though all orphan diseases together affect only about 10 per cent of the population. Sales for orphan drugs were similarly disproportionate, accounting for more than 13 per cent of all drug sales in 2012. As a result, the market for orphan drugs is projected to grow at double the rate of the overall prescription drug market through 2022.

Kenneth Kaitin, director of the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, thinks this is a serious problem. ‘Human disease around the world isn’t a collection of rare diseases,’ he told me. ‘It’s a collection of common diseases – cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes. And right now the market is pushing [industry] into these rare diseases, and away from much more common problems that affect many more people.’

As a result, Kaitin says fewer resources are being invested in new treatments for these common problems. He cites cardiovascular disease as an example, where research into new therapeutics has lost momentum in recent years even as cardiovascular disease remains a leading cause of death. Tropical infectious diseases have long suffered from a lack of financial incentive in the development of treatments. Antibiotics are another example – despite urgent need for novel antibiotics due to increasing resistance, few companies are interested because they don’t see the potential for large profits. This is leading us toward a ‘huge crisis in the near future’, according to Kaitin.

Orphan drugs illustrate how financial incentives distort the development of treatments in ways that don’t always provide the greatest benefit. Before the Orphan Drug Act, rare diseases weren’t attractive to developers despite real human need. And after the Act, although many people suffering from rare diseases have benefited, more pressing concerns have been sidelined in pursuit of profit.

The market can also influence lifestyle choices and health interventions not so easily commodified and sold as a pill. Here, the history of disease in the 20th century has followed two broad arcs. Death from infectious disease dropped precipitously, due to radical advances in sanitation and public health in the 19th century and development of antibiotics and vaccines in the 20th century. As infectious diseases declined, other more chronic killers became common – cardiovascular disease, diabetes, stroke, cancer.

The question of why these diseases occurred was obscure at first, but the rapid development of medical science in the early 20th century allowed scientists to begin to unravel their mechanisms. And once the mechanics of a disease began to yield their secrets, researchers could develop drugs to treat.

The first of these was insulin, which was extracted from a slurry of dog pancreas in 1921 by a Canadian surgeon named Frederick Banting. The following year, Banting demonstrated its efficacy in human diabetes, and contracted with pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly to produce and market the drug. The partnership would prove auspicious – insulin became a major commercial and medical success, assuring Eli Lilly a dominant position in the industry and Banting a Nobel Prize.

Banting’s partnership with Eli Lilly had deeper historical significance as well. The company was among the first to produce high-quality medications for use by physicians, as opposed to the common and dubious ‘patent’ medications hawked by snake-oil salesmen. Eli Lilly pioneered the use of several modern practices, like quality control, ingredient labels, and gelatin capsules.

Eli Lilly became the prototype of the modern pharmaceutical company. Its collaboration with Banting augured the development of a partnership between physicians, scientists and industry which remains the dominant mode for developing new treatments to this day.

Even as medical science charged forward in its efforts to develop drugs, it remained unclear why these chronic diseases occurred. That began to change with a pivotal event in the closing weeks of the Second World War – the sudden death of President Franklin Roosevelt from stroke in April 1945. He was just 63 years old.

Roosevelt had suffered from hypertension and heart failure, according to his physician, who had little to offer other than bed rest. In the wake of his death, the dearth of knowledge regarding the underlying causes of cardiovascular disease drew national attention. Roosevelt’s successor, President Harry Truman, signed the National Heart Act into law in 1948, creating a new National Heart Institute and sponsoring a longitudinal study of cardiovascular disease.

it’s a landscape that follows naturally from the premise that healthcare should be an industry, not a service

The Framingham Heart Study was launched later that year. Scientists collected extensive information from participants in Framingham, Massachusetts, and tracked them over time, searching for factors that might predict cardiovascular disease. It was in Framingham that researchers discovered that smoking, high blood pressure, elevated cholesterol, and obesity were associated with cardiovascular disease, and that exercise was protective.

The Framingham study revolutionised attitudes toward diseases like hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Before Framingham, physicians viewed these problems as merely a function of ageing, and just as inevitable – the idea of a ‘risk factor’ didn’t even exist. But after, it was evident that these diseases emerged from factors that could be intervened upon.

Framingham provided a glimpse of the lifestyle factors that could be associated with chronic disease, but its legacy would be the use of medications to target the physiological factors it had uncovered, like cholesterol and blood pressure. Behavioural changes like weight loss, exercise, and eating well have received less emphasis, even as contemporary research supports the idea that their opposites – obesity, sedentary lifestyle, and poor nutrition – dramatically increase risk of chronic disease. Environmental factors have also been left out, like air pollution and its effect on asthma.

It’s not hard to see why these elements received less focus. By the 1950s and ’60s, US healthcare was already almost fully commodified. The partnership between science and industry that began with Banting’s work with Eli Lilly was in full effect, and a host of new medications were being produced to manage chronic disease.

The health insurance industry was also in ascendance – by 1958, 75 per cent of Americans had private health insurance designed to provide coverage for hospitalisations and prescription medications, not for the development of healthy habits. And the dominant model for physician compensation was fee-for-service, whereby doctors are paid for intervention rather than prevention.

All of these factors – from the early partnership between industry and science by Eli Lilly and Banting, to the legacy of Framingham in our treatment of physiological risk factors, to the design of the current system of physician reimbursement and health insurance – meant that drugs, which could be bought and sold, were prioritised over lifestyle changes, which couldn’t.

For many diseases, this system has been effective. Death from cardiovascular disease has dropped precipitously, and we now have dozens of medications to manage diabetes and high blood pressure. Life expectancy has grown by 30 years since 1900. But the medications that gave us these achievements don’t provide a cure – rather, they offer control without addressing the underlying cause. As a result, patients must often take them for life. And that has proven enormously fortuitous for the companies that make these medications. Statins, for example, are projected to approach $1 trillion in sales by 2020. Insurance companies benefit too, because regulations allow them to take a fixed percentage of expenditures as profit. Put a different way, the more insurance companies spend, the more they make, with the true cost falling to the general public via rising premiums.

This landscape, wherein patients with chronic disease take dozens of pills daily in a kind of détente with their illness, isn’t the product of some conscious conspiracy by the pharmaceutical industry. Rather, it’s a landscape that follows naturally from the premise that healthcare should be an industry, not a service.

Healthcare in the US is not likely to rid itself of its obeisance to the market any time soon. But what if financial incentives could be co-opted to address the lifestyle factors underlying chronic disease? What if we could make those interventions lucrative somehow?

Maybe we can. Chronic disease is expensive – cardiovascular problems alone cost the US more than $300 billion in 2012. Addressing the underlying causes has the potential to save us an enormous amount of money. The trick is linking the expense of sponsoring lifestyle changes with the financial reward of long-term savings.

Dean Ornish, now a well-known physician and author, has been thinking about this puzzle since the 1990s. Armed with studies showing that lifestyle change could reverse heart disease, in 1993 Ornish approached one of the largest health insurers in the US with a proposition: offer coverage for his program and reap big savings down the line. The company took the gamble, and won. Subsequent studies found that the Ornish program reduced expenses for invasive cardiac procedures over three years by nearly 50 per cent, and cut hospital admissions by more than 80 per cent.

Despite these early results, many health insurers remained skeptical.

A major reason for their skepticism is that most Americans switch insurers every few years, according to Hilary Seligman, a physician at University of California, San Francisco. This means that if one insurer decides to invest in lifestyle change for its customers, the subsequent savings are likely to accrue to a different insurer as those customers move from company to company in search of better prices.

But Seligman thinks that lifestyle changes – especially diet – can be powerful enough to provide savings even in the short term. She’s involved in a large trial underway in California to examine whether distributing nutritious meals to patients with heart failure or diabetes can cut costs. The trial will build on smaller, earlier studies that showed promising results: a study in Philadelphia found that medically tailored meals decreased total monthly healthcare costs by an astonishing 25 per cent for the patient group as a whole. A similar study in San Francisco showed a strong trend toward decreased hospitalisation.

Large health insurers are starting to take note. A momentous advance came in 2010, when the US national health insurance program, Medicare, agreed to offer reimbursements for the Ornish program. By 2016, major insurers like Aetna, Blue Shield of California, Anthem, and Highmark were offering reimbursements as well.

the commodification of healthcare distorts the shape of medical treatment, and influences what therapies are available to patients

These are promising developments for chronic illnesses that seem to have a clear lifestyle component, like cardiovascular disease and diabetes. But what about other maladies related less to lifestyle, like autism, autoimmune disease, or tropical infectious diseases? Are there other ways to develop effective treatments in the absence of strong market incentives?

One route could be through nationalised healthcare. In the United Kingdom, for example, the National Health Service promotes collaborative research networks investigating rare diseases, and invests directly in neglected disease research rather than using incentives that are vulnerable to exploitation. And once a new treatment is developed, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence reviews clinical and economic data to negotiate a price more closely aligned with a drug’s value. A major benefit of this system is that the UK has some of the lowest prescription drug prices in the world, although some detractors believe the model discourages innovation.

There are nimbler possibilities, too, which don’t rely on the brute force of a large public sector. After winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1999, the non-profit organisation Doctors Without Borders used its prize money to launch the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative, known also as the DNDi. Its mission is to leverage partnerships across academia, government, and industry to develop new treatments for diseases. The organisation isn’t beholden to the prospect of profit, and can focus on diseases that pharmaceutical companies have tended to ignore. Most funding comes from private philanthropy, though, leading some to question its sustainability.

Nevertheless, it’s proving to be an astonishingly effective model. The initiative has gained approval for six new treatments for neglected tropical diseases, and has 26 more in development. It’s accomplished this with around $300 million – a fraction of the $1.4 billion that large pharmaceutical companies spend on average to develop a single drug.

The organisation has now turned its attention to developing new treatments for diseases common in the developed world, beginning with hepatitis C. As mentioned before, current therapies for hepatitis C are effective but extraordinarily expensive. The DNDi is conducting clinical trials of a much more affordable treatment regimen in Malaysia and Thailand. And in 2015 the initiative began working on new treatments for antibiotic resistant infections. Many observers are watching closely to see whether the organisation’s methods can be applied to other diseases common to the developed world.

Criticism of the market’s influence in healthcare is nothing new. But that criticism has often been exclusively economic, focusing on runaway costs and spending. Far less attention has been paid to how the commodification of healthcare acts to distort the very shape of medical treatment, and influences what therapies are available to patients.

If we don’t recognise how the market works against us, how will we ever come to make it work for us?