Detail from Ophelia 1851-2 by Sir John Everett Millais. Photo Courtesy Tate/Wikipedia

More than any other disease, tuberculosis (TB), or consumption, shaped the social history of 19th-century Europe. Its impact on the artistic world was just as powerful, with artists offering their own commentaries on the disease through painting, poetry and opera. Consumption was almost a defining feature of Romanticism, the style of expression for which the era was known.

According to The White Plague (1952) by René and Jean Dubos, Caucasian patients took on a profoundly anaemic countenance as they lost blood and iron – thus the title of their great history of the disease. The consumptive model Elizabeth Siddal, best known as the drowned Ophelia in John Everett Millais’s pre-Raphaelite painting, became an icon for her generation. Fashion-conscious, healthy women starved themselves and chemically whitened their skin to mimic this ‘consumptive’ look. Lord Byron, the most notorious of the Romantic poets, quipped that the affliction would have ladies saying: ‘See that poor Byron – how interesting he looks in dying.’ Indeed, the preponderance of Romantic writers, painters and composers with TB created a myth that consumption drove artistic genius. Many assumed that the spes phthisica, a kind of elation that intermingles with depression during the disease, elevated the mind.

The truth, of course, is that TB’s impact on the arts was merely a reflection of the savagery with which it ravaged the general population – artists and everyone else. In 1801, up to one-third of all Londoners died from TB. Yet its course was insidious, with some victims dying slowly over months, and others – years. Talented victims, all of them doomed before the age of antibiotics, had time (paraphrasing Keats) for their pens to glean their teeming brains, in spite of, not because of, the disease.

Then as now, the disease is caused by the transmission of the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis in sputum from infected individuals. TB germs land in their victim’s lungs and proliferate, provoking inflammation, severe coughing and breathlessness. Fevers and sweats ensue. Eventually, pulmonary blood vessels rupture, contributing to the anaemia that makes complexions pale. Apart from consumption, the disease comes with many synonyms. The word ‘phthisis’, from the Greek, meaning a wasting disease, was in use before we came up with the name TB. The nasty-sounding name ‘scrofulae’, derived from the Latin for ‘little pigs’, referred to swellings that appear around the body when bacteria spread beyond the lungs, was also widely used.

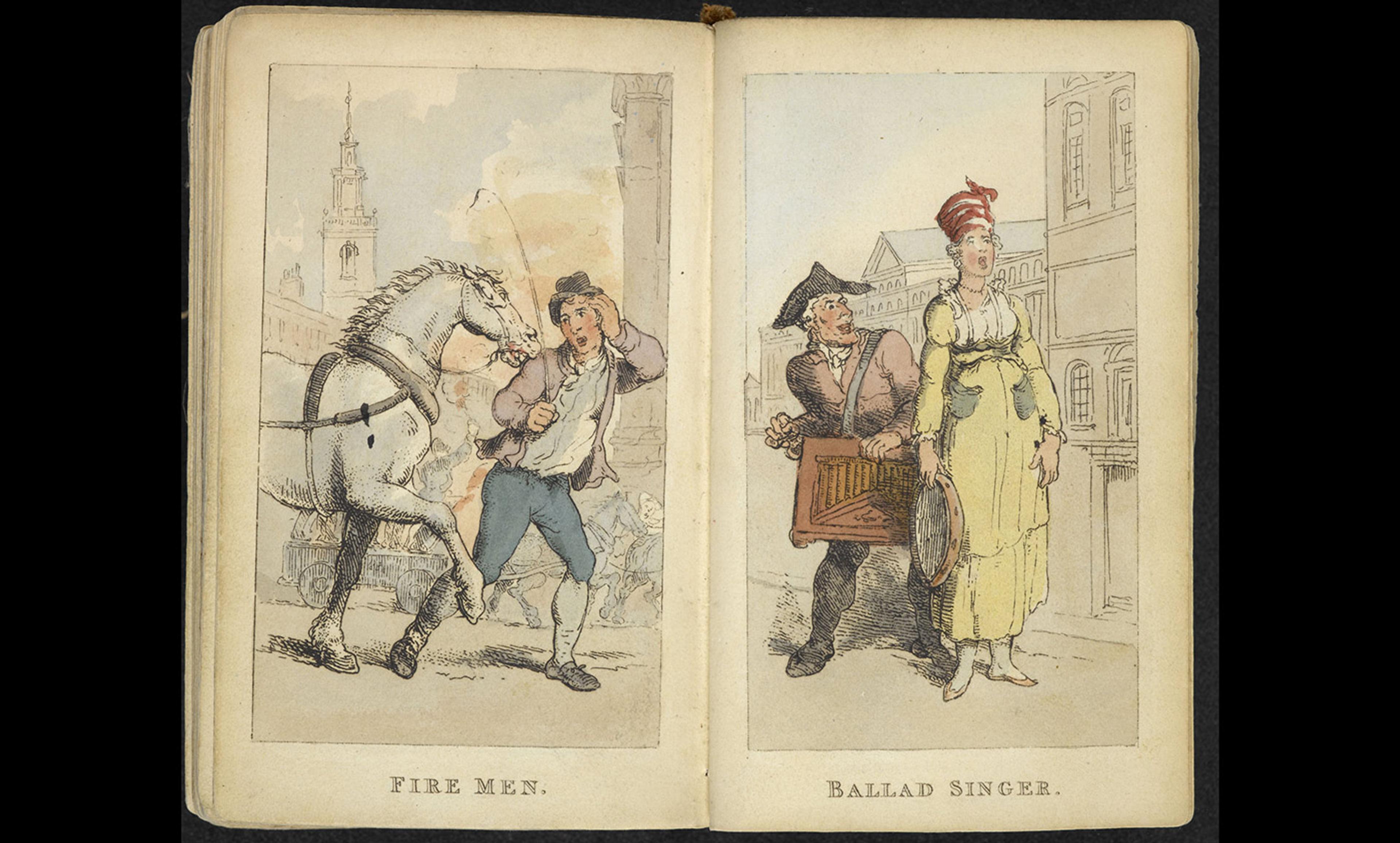

Epidemic TB erupted with the arrival of the Industrial Revolution. Expanding cities, filth and persistent human contact fuelled the disease. Like TB, Romanticism arose in response to growing urban squalor. Artists evoked rural idylls and mythical classicism to counterbalance its horror. Later in the 19th century, when city-planning reduced overcrowding, both TB and reactionary Romanticism retreated.

Of all consumptive artists, John Keats (1795-1821), an English medic turned poet, is most often associated with the disease. His mother had died from it, and a younger brother Tom, too, before Keats himself succumbed aged just 25. His final year frustrated by tragic love, declining health, departure for Italy and eventual death represents the archetypical decline of a Romantic consumptive.

Keats’s poetry offers insight into the machinations of a medically qualified mind, mingling with Romantic philosophy trying to understand phthisis. His ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ (1819), written as he grew suspicious that he was afflicted, offers florid descriptions of the key symptoms of the disease. In it he describes ‘the weariness, the fever and the fret’ associated with a condition in which ‘youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies; where but to think is to be full of sorrow and leaden-eyed despairs’, and where the ‘the dull brain perplexes and retards’.

Another poem composed that year, ‘La Belle Dame sans Merci’, takes as its central character a knight-at-arms. By the time it was published in 1820, the knight had been demoted to a ‘wretched wight’ – a dishevelled, ailing individual common in medieval literature. Many have identified Keats himself as the knight/wight and the transformation coincides with his own metamorphosis from a confident poet into a blood-coughing wreck. The poem follows the wight’s whirlwind relationship with a fair maiden who has left him colourless, feverish and hallucinating about others who also met her and the same consumptive fate.

Robert Graves, in his erudite monograph on poetic inspiration The White Goddess (1948), claims that La Belle Dame was herself ‘consumption; whose victims warned him [the knight/wight] that he was now of their number’.

Across Europe, the epidemic raged. In Russia, Anton Chekhov’s late plays depicted consumptive exiles fretting in the Black Sea resort of Yalta where the playwright, a doctor himself, convalesced before dying of TB, aged 44. His Three Sisters (1901), a play full of doom, gloom and the trials of complicated romance, echoes the lives of the Brontë sisters, all of whom died from TB in mid-19th-century Yorkshire. The painting of Anne, Emily and Charlotte Brontë, which hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London, shows a disturbing ghostly blur in the background, created by the artist, their brother Branwell, who might have excised himself from the picture in a fit of despair, knowing of his own impending tuberculous death.

Italian opera in the 19th century celebrated consumption, too. Giuseppe Verdi’s La traviata, first shown in 1853, traced the death of poor Violetta whose final stages of the disease erupted when she was denied the chance to marry her lover Alfredo. In Giacomo Puccini’s La bohème, the tuberculous heroine Mimì is abandoned by her lover Rodolfo. Puccini’s opera wasn’t staged until 1896, after Romantic notions of consumption had been dispelled by Robert Koch’s pivotal demonstration in 1882 of a bacterial cause. Was Rodolfo’s abandonment of Mimì because of his fear of contagion?

Although TB didn’t end with the 19th century, its link to a romantic ideal did. There was nothing noble or lofty when confronted by the stark truth of noxious germs gnawing away inside their victims to cause the disease once known as scrofula.