Druze farmers. Photo courtesy Wikipedia

It is in what we now call the Middle East that humans domesticated plants and animals, built the earliest cities, devised the first alphabet, and wrote the first literature. But while many of the mysteries in the region’s history still abound, few have attracted more varied speculation than the origin of the Druze people and their religion. Modern genetics gives us powerful new tools to decipher the origin of the Druze.

Much like the Ashkenazic Jews, the origins of the Druze people and religion have fascinated historians, linguists and geneticists. For nearly a millennium, travellers and their neighbours have wondered and hypothesised about the beginnings of this enduring people, and their exclusive religion in the mountains of Israel, Syria and Lebanon. Benjamin of Tudela, the Jewish traveller who passed through Lebanon in 1165, was one of the first European writers to refer to the Druze by name. Even then, they were known as mountain-dwellers, and Benjamin described them as fearless warriors who favoured the Jews. But he could not state their origin, and he was not the only one to be mystified. Over the years, people have proposed that the Druze have Arabian, Persian or Near Eastern origins.

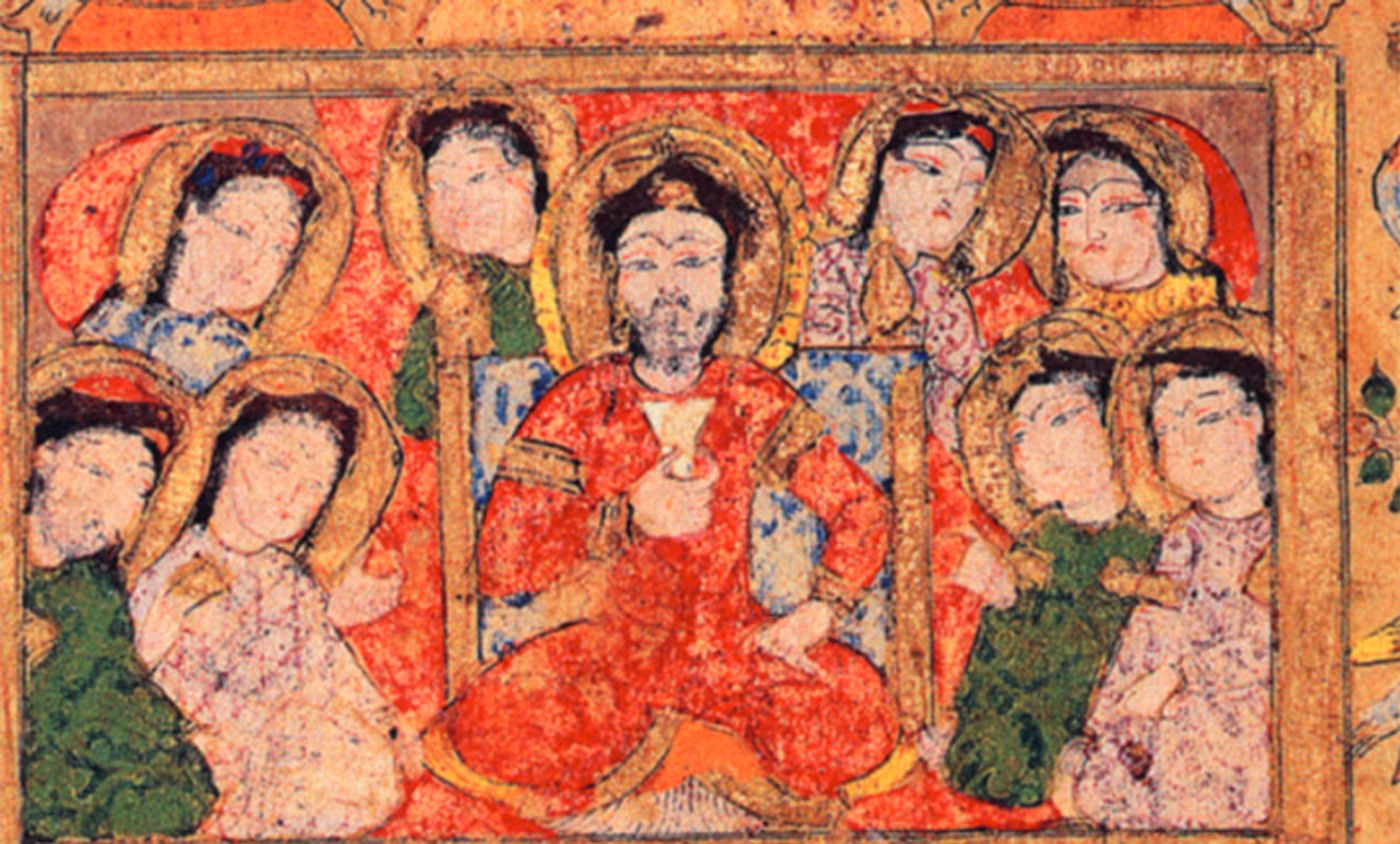

Reports from Cairo’s ruler, Al-Hakim (996-1021 CE), give us the first glance into the Druze and Druzism. Al-Hakim had sent missionaries throughout Arabia, to win new believers. His missionaries claimed the Druze had splintered from Isma’ili Islam, a branch of Shia Islam. After Al-Hakim’s sudden disappearance, the new ruler eradicated the faith in Cairo. The Druze who took residence in the mountains of what is now Lebanon, Syria and Israel not only survived, but flourished. Since the 11th-century Crusades, the Druze have played a distinctive role in the region. Also in the 11th century, the Druze closed their faith to new adherents. You cannot become a Druze. This exclusivity also means that modern-day Druze people contain the genetic signature of the their Druze ancestors.

The Geographical Population Structure (GPS) technology, which works in a similar way to the satnav geolocation system, uses DNA instead of satellites to predict the most recent geographical origins of a DNA sample. To infer the origin of Druze ancestors, my lab at the University of Sheffield has applied the GPS technology to the DNA of Israeli Druze.

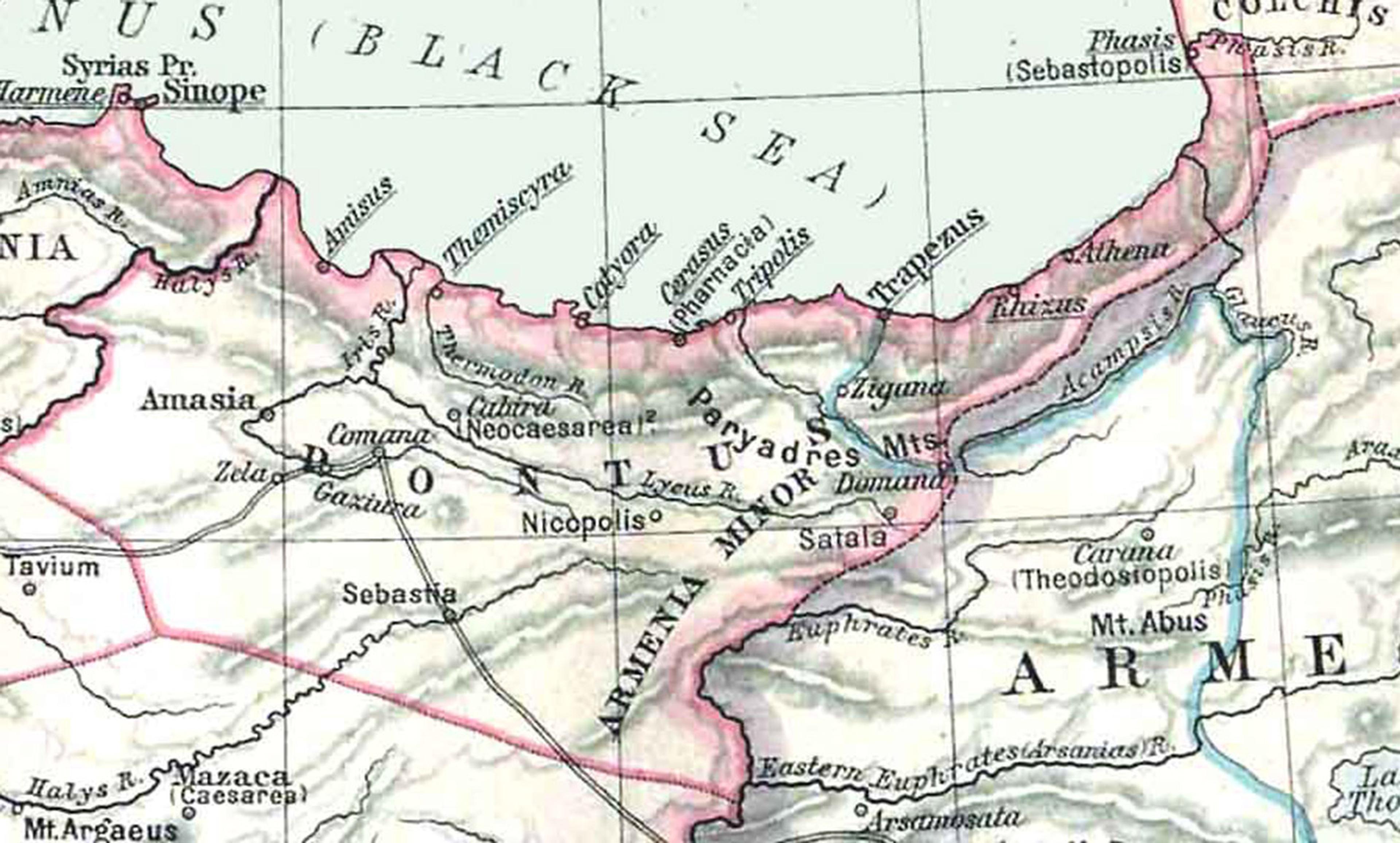

Most of the Druze, we have found, can be traced to the highest mountains in Turkey, northern Iraq and southern Armenia, and to the Zagros Mountain belt bordering Mount Ararat – very close to ancient Ashkenaz. By comparing the DNA of contemporary Druze to DNA dated 1,000-4,000 years ago from the Levant, Turkey and Armenia, my lab confirmed these findings. This means that, genetically, the Druze really are different from their neighbours. Unlike Palestinians, Bedouins and Syrians who share between 36-70 per cent of ancient Levantine ancestry, the Israeli Druze have only a minor Levantine component of 15 per cent and a significantly higher (80 per cent) ancient Armenian ancestry. Ashkenazic Jews, by contrast, had a major ancient Anatolian ancestry (96 per cent) and a residual Levantine one (0.5 per cent), in support of their non-Levantine origins.

The Druze have long preferred to live among high mountains, which has helped them maintain their close social structure, as well as providing them with protection. Our results indicate that the Druze habitation in high mountains is an ancient practice, one that their ancestors brought with them from what is now Iraq, Armenia and Turkey. But why did they come to the Middle East? Can DNA help us answer that?

Fortunately, since the Druze maintain a close-group social structure, each group preserved a different aspect of the Druze history. Genetic testing is thereby able to determine that the Druze DNA experienced its last major admixture event, where Druze mixed with local Levantines (Syrians), between the early ninth century and the early 12th century. The date overlaps with the expansion of the Seljuk Turkish Empire into the Levant during the 11th century to fight the Crusaders. We know that after pushing away the invaders, the Seljuks settled in Iran, Anatolia and Syria, and that the Druze were first recorded in that region around 150 years later. The genetic similarity between Druze and Armenians supports speculation that they had Seljuk ancestors. Most likely, the Seljuks would have, upon their arrival in the Levant for the Crusades, mixed with the native population. Some of them would have likely adopted the Druze faith. The Druze genome is therefore like a very long museum with separate rooms for Near Eastern and Levant exhibits, and including rooms for mixed inheritances that could not be sorted. Now, we can put together the remaining evidence to reconstruct the Druze’s history.

The Near Eastern ancestors of the Druze emerged near the Fertile Crescent, in the region that saw the rise of domestication and agriculture. Unsurprisingly, it was also a major convergence point on the Silk Road, with trade routes leading to Constantinople and Antioch. This is when the Druze likely encountered the Ashkenazic Jews who played a key role in global trade. The genetic similarity between Druze and Ashkenazic Jews is very high, although they emerged from different ancient founding populations (Anatolians and Armenians). However, although they started at the same place, they went their separate ways. By the eighth century, Ashkenazic Jews had abandoned ancient Ashkenaz and moved north to Khazaria and west to Europe. Two centuries later, the Druze ancestors began descending to the Levant to fight in the Crusades.

When the Druze reencountered Ashkenazic Jews in Palestine centuries later, neither population recalled its Near Eastern origins, and both peoples developed a rich heritage based on their experience over the previous millennium. However, as both populations, to a large extent, favoured marriage within the community, each retained Near Eastern relics in its DNA museum, which allowed us to tell the end of this 2,000-years-old odyssey.