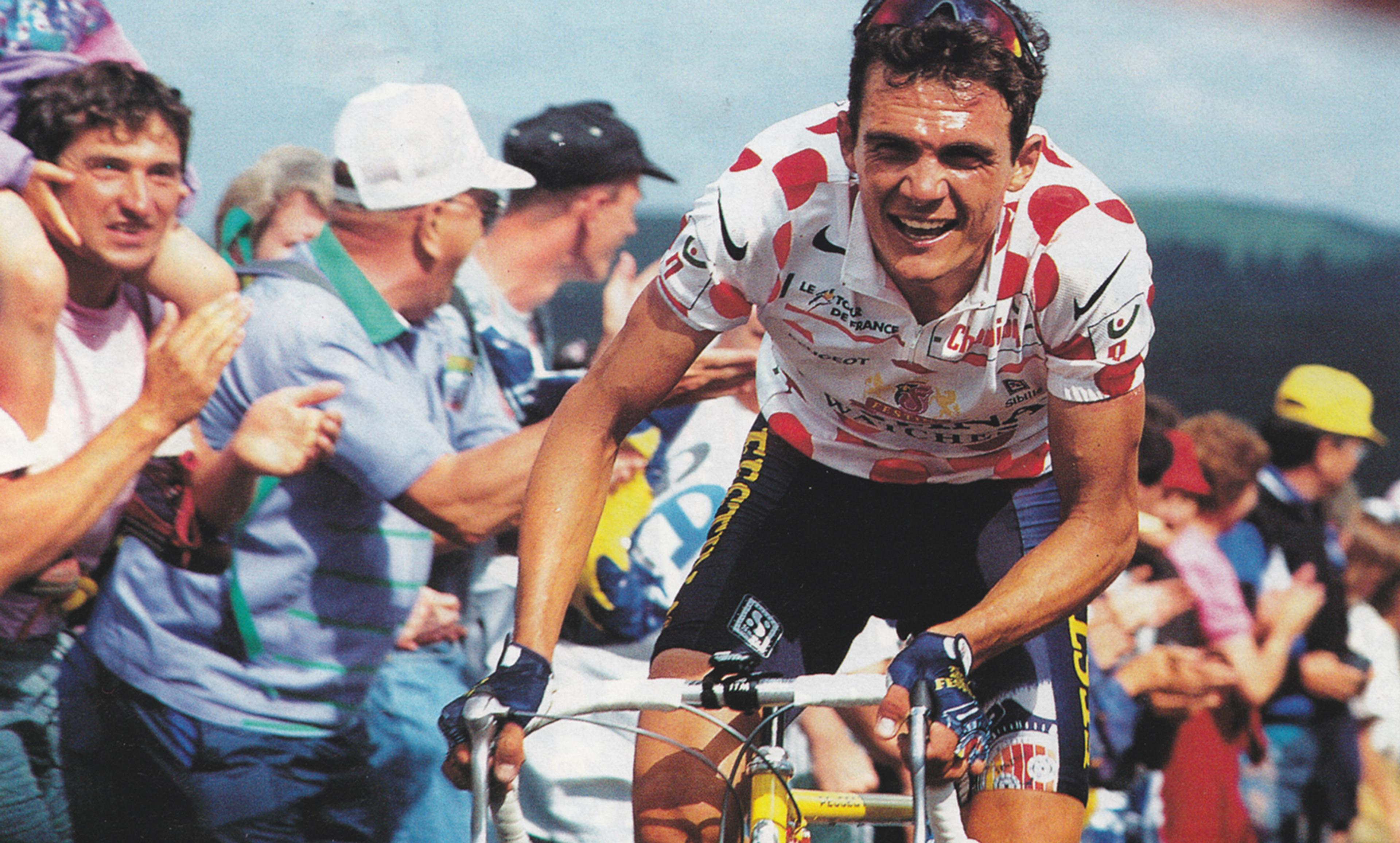

Richard Virenque of the Festina team in the 1995 Tour de France. Photo by Anders/Flickr

Doping in sport is widespread and shows little sign of abating. Athletes are dropping out of the Rio Olympics like flies. Maria Sharapova was banned for two years after testing positive for meldonium; a Romanian kayaking team failed their drug test, disqualifying them pending further investigations; and the International Olympic Committee announced that they could ban up to 31 athletes from competing because retests of their samples collected during the 2008 Beijing Olympics indicated the presence of banned substances. If the trend continues, the Rio Olympics could be the Olympics with the lowest number of delegations in recent history.

The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) have taken the unheard-of move of banning the entire Russian track and field delegation of athletes on grounds of systematic doping. WADA works on the premise of strict liability, which means that athletes are deemed guilty whether or not they realised that they had taken a banned substance.

However, despite continued efforts, the practice of doping persists and seems to be so entrenched in professional sports that no doping sanctions, however harsh, will be able to eradicate it.

Researchers who study doping in sport have identified a series of factors that explain its continued presence. Many of these can be summarised as the so-called ‘payoff matrix’ that athletes face in professional sports. Put simply, the rewards – prize and sponsorship money, records, fame and the rest – continue to outweigh the risks of doping, which include not only being caught and punished, but also physical harm to the athlete.

Many athletes decide that the risks are worth it, and continue to trade future health problems for short-term competitive advantage. The professional sport system incentivises record-breaking and superior performance through prizes, sponsorship money and front-page headlines. Meanwhile, escaping from this payoff matrix can be extremely difficult for athletes who want to compete at the highest levels. Empirical data suggest that athletes often dope as a result of extreme psychological pressure: they feel they have no alternative. Alex Zülle, for example, a former Swiss professional cyclist who rode for the Festina team and who tested positive for erythropoietin in 1998, said:

Everybody knew that the whole peloton was taking drugs and I had a choice. Either I buckle and go with the trend or I pack it in and go back to my old job as a painter. I regret lying but I couldn’t do otherwise.

Hence, while choosing not to participate in doping is theoretically possible, in practice it is not easy. The choice not to participate can be extremely costly for the athletes, as it can amount to giving up being competitive, or even leaving the profession. Though the language of ‘no choice’ is hyperbole, for sportspeople who have focused every aspect of their lives for decades on high achievement in their chosen sport, quitting or competing only at a lower level might not even seem like an option.

Ultimately, the persistence of doping – by individuals on an isolated basis, and by whole teams as part of a systematic doping programme – means that professional sport today is rarely – if ever – untainted. Many athletes have become little more than ‘guinea pigs’ in this system.

What can be done about this?

One apparently simple solution would be to legalise doping and make it part of sport. The philosopher and bioethicist Julian Savulescu has suggested this, with the proviso that drugs be used ‘under medical control’. Competitors would be allowed to take performance-enhancing drugs as long as they were ‘safe’, where the bar of safety ‘should be set at the level we allow athletes as persons to take risks’.

Would that solve the problem of widespread doping in sports? I do not think so.

Secretiveness is an integral part of achieving and maintaining competitive advantage in any context, and for professional athletes the option to ‘take and hide’ would remain the rational choice if doping were legalised. This is a classic example of a game theory problem where the other options are ‘take the drug openly’, ‘don’t take it, and hide’, and ‘don’t take it openly’. As long as the payoff matrix of professional sport remains unchanged, lifting the ban on doping would not lead to ‘safe doping’ under medical supervision, but would instead result in a two-tiered system of doping where, in order to maintain competitive advantage, athletes would continue to take dangerous performance-enhancing substances secretively.

The only way to make professional sports sustainable, I argue, is to transform the financial matrix that supports and endorses it.

How can we do that? We can start with the idea that athletes should not be the only ones held to account (in the sense of liability) for doping. In practice, this means changing WADA’s system of strict liability for the athlete. To do so, we first need a stakeholder analysis to understand who the relevant stakeholders are for each team, athlete or sport. WADA could require teams or individual athletes and their entourages to submit something akin to a classic organisational chart, showing who reports to whom, who pays whom, and who makes decisions for whom.

The next step would be to assign liability to the appropriate stakeholder(s). Here, we think that the individuals identified through the stakeholder analysis as possessing the most power or control over the ‘organisation’ should be held personally liable for the doping of the athlete(s) under their control. In some cases, the organisations themselves will have corporate responsibility. Of course, we recognise that individual athletes retain considerable responsibility for their own actions even if under duress or psychological pressure. So athletes who test positive for doping should still be excluded from competition for a certain period of time.

Assigning liability to those who wield power over the athlete(s), entourage or team would be practically possible: there are regulations and laws in other contexts that could serve as a model. After the Enron scandal of 2001, for example, in which the large US company lied about its finances, the US Congress passed a law called the Sarbanes-Oxley Act that makes the top managers of a publicly traded company personally liable for any financial fraud that anybody in their company commits, as related to that company. Applied to sports, we could envision regulation that holds the team owner, the individual athlete (in the case where he or she sits at the ‘top of the organisation chart’), or even the manager from the sponsoring company in charge of the sponsorship contract, personally liable (ie, responsible for paying a large fine) if any member of the team, entourage or athlete is found to be in violation of a doping rule. Important details would need to be worked out, such as the size of the fine, and the issue of preventing lawsuits and scapegoating.

The problem of doping in sport is not about to go away. Legitimising safe doping under medical control will do little to prevent clandestine use of dangerous performance-enhancing substances. The only practicable solution we can see is to widen the search for those who are culpable, not absolving the doping competitors from guilt, but recognising that those who control the ‘payoff matrix’ have at least as much responsibility for the corruption of sport as do the athletes themselves.