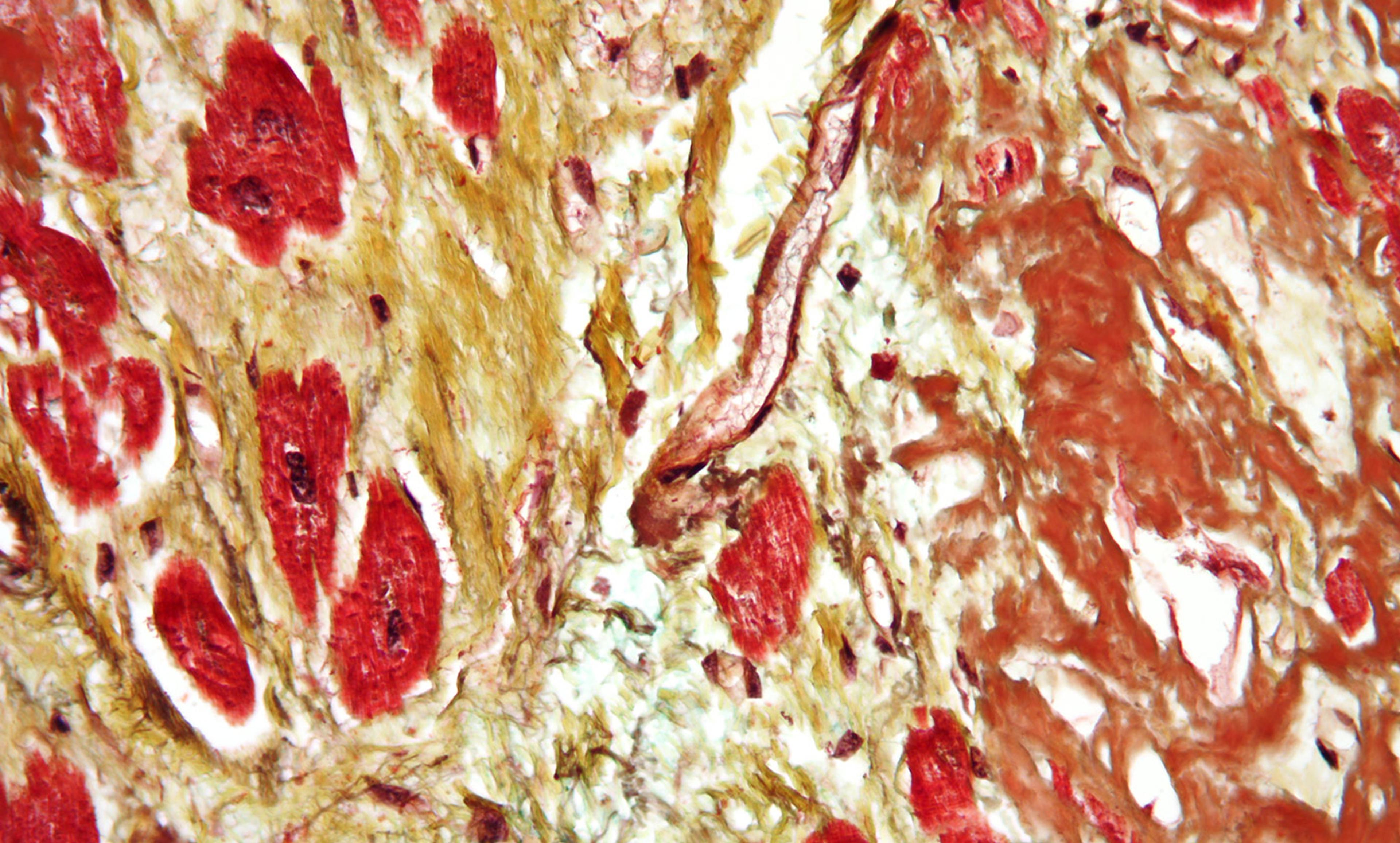

Cardiovascular disease. Photo courtesy Wikipedia

Cardiovascular diseases represent the main cause of death in the European Union and in the world. Yet, compared with men, women suffering heart attacks are less likely to get treated on time, and their chances of being diagnosed correctly, and receiving beneficial medication and advice, are much lower.

This is just one example of the prejudice women face in seeking healthcare. For instance, I recently went to my gynaecologist and on his table I saw flyers on birth-control pills. All the essentials were explained, save one: the necessity of checking whether a woman is predisposed to cardiovascular diseases (CVD) or congenital heart disease before taking the pill; and this requirement should be compulsory. In fact, some birth-control pills tend to increase women’s blood pressure, so if a woman has other risk factors for heart disease or thrombosis, the hormones in the pill could compound that risk.

It appeared that doctors, and society at large, labour under the widespread belief that women don’t have much of a cardiovascular problem, when compared with men. My research has borne that out: the chance that a woman will be undertreated for a cardiovascular issue is greater than for her male counterpart. In 1991, Bernardine Patricia Healy, the first woman to become director of the United States National Institutes of Health, called this phenomenon the ‘Yentl syndrome’.

Yentl, the heroine of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s story ‘Yentl the Yeshiva Boy’, had to cut her hair like a boy to seek higher education. Healy argued that, to be properly treated in the healthcare system, women with CVD had to look like a man too. In fact, in the institute that Healy directed, women with CVD were less frequently diagnosed and hospitalised, and received fewer surgical remedies, than men. And they were underrepresented in clinical trials of cardiovascular drugs, too.

Pushback has finally begun to appear in the medical peer review literature. The cardiologist Rita Redberg of the University of California, San Francisco reports that women are underrepresented in epidemiological studies on prevention and risk. A US study published in 2016 shows that, compared with men, women are less likely to receive potentially beneficial medications such as aspirin and cholesterol-lowering drugs, or to get advice about quitting smoking. The American Heart Association has also just published its first-ever scientific statement on acute myocardial infarction (death of heart muscle) in women, contending that ‘sex-specific differences exist in presentation, pathophysiological mechanisms, and outcomes in patients’ – in other words, unless doctors understand the disease as it presents in women, it’s going to be missed.

Three culprits are at the root of this ongoing problem in women’s heath. First, and especially critical, the samples used for scientific research often exclude sex as a critical biological variable in study design. The cardiologist Nanette Wenger at Emory University in Atlanta points out that, even in early stages of testing, pharmacological studies generally use male animals. Then findings are translated to the white male population, hardly sufficient to address knowledge gaps across individuals of different sexes or hormonal status.

The second culprit relates not to sexual or hormonal differences per se, but to differences in gender: that is to say, to psychological, environmental, social and cultural factors. Important factors here include gender identity and life cycle, differences in communication, and likelihood of getting diagnosed with, or treated for, a given disease in the first place. These social and cultural elements are often not taken into account, even when researchers seek neutrality.

Finally, risks increase when women present with ‘atypical’ symptoms – disease presentations different from those reported by men – causing physicians to miss the disease. For instance, when women have myocardial infarction, they often don’t have chest pain, but pain in the neck or in the back, or even no pain at all, just a feeling of restlessness, anxiety and laboured breathing. Even the age of risk might differ: heart-disease risk in women appears to rise after menopause.

As many feminist thinkers have pointed out in recent decades, science and Western medicine must give up its pretentious neutral gaze, cast from the unmarked position of white men. ‘Gender blindness in medicine means many physicians are unaware that a great deal of existing medical knowledge is founded on knowledge of the male body as the prototype of the human body,’ as a Dutch researcher wrote in 2010.

Sex and gender-blindness challenges claims of neutrality in medicine. When we automatically impose the white male subject on to all sexes, genders and racial groups, objectivity is erased. Under such a system, knowledge is merely partial. Only by recognising unexplored zones can we start to build a more accountable and reliable system of medicine in the years to come.